Restrictive U.S. 1924 Immigration Act Boosts Jewish Immigration to Palestine

May 26, 1924

Between 1880 and 1920, more than 20 million immigrants entered the United States, including more than 2 million Jews. Xenophobia and fear of competition for jobs and land prompted Congress to pass the 1924 Immigration Act, known as the Johnson-Reed Act. The outbreak of World War I had caused immigration to decline, yet Congress continued to pass restrictive immigration laws that required literacy tests and established quotas. Although immigrants were critically needed for America’s rapid industrialization and expansion, large-scale immigration was met with great trepidation.

The 1924 Immigration Act restricted immigration from any one country to 2% of that country’s residents in the United States as of the 1890 census. If, for example, there were 100 immigrants from a specific country according to the 1890 census (before the immigration boom in the first decade of the 20th century), then only two immigrants from that country would be permitted in 1924.

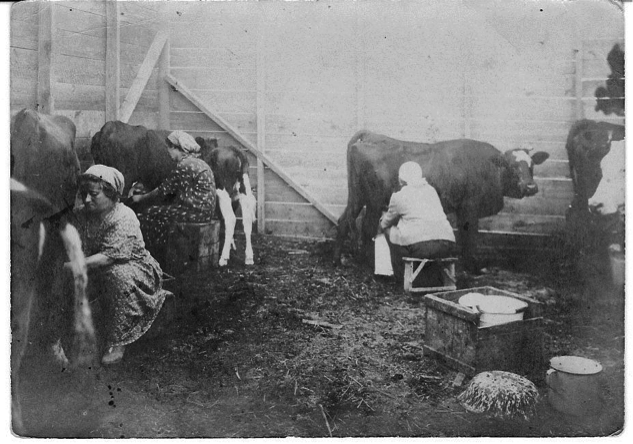

As a result, the law was especially restrictive for immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe, countries from which large numbers had immigrated to the United States after 1890. These regions had high concentrations of Jews who were facing persecution, were desperate to leave and now had to create an alternate plan. Unable to immigrate to the United States, many European Jews made aliyah to the land of Israel. Between 1924 and 1929, the period known as the Fourth Aliyah, 82,000 Jews immigrated to Palestine. This was the largest number of immigrants since the beginning of the modern Zionist movement. The Fourth Aliyah was crucial for the country’s continued development and had a major impact in the emerging urban areas. The photo shows Fourth Aliyah pioneers milking cows at Moshav Kfar Hassidim in Emek Zevulun. The moshav was founded by religious immigrants from Poland in April 1925.