The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann

January 1937 – December 1938

Volume XVIII, Series A

Introduction: Aaron Klieman

General Editor Barnet Litvinoff, Volume Editor Aaron Klieman, Transaction Books, Rutgers University and Israel Universities Press, Jerusalem, 1979

[Reprinted with express permission from the Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel,by the Center for Israel Education www.israeled.org]

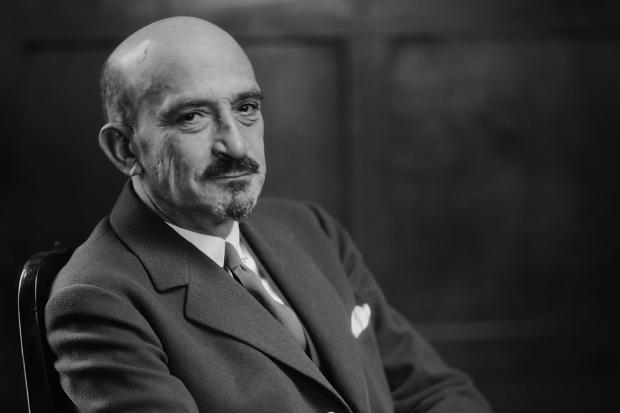

As mirrored in this volume of his letters, the years 1937-38 were for Chaim Weizmann the most critical period of his political life since the weeks preceding the issuance of the Balfour Declaration in November 1917. We observe him at the age of 64 largely drained of physical strength, his diplomatic orientation of collaboration with Great Britain under attack, and his leadership challenged by a generation of younger, militant Zionists. In his own words he was ‘a lonely man standing at the end of a road, a via dolorosa. I have no more courage left to face anything—and so much is expected from me.’

This situation found its prelude in 1936, when Arab unrest compelled the British Government to undertake a comprehensive reassessment of its policy in Palestine. A Royal Commission headed by Lord Peel was charged with investigating the causes of the disturbances. Weizmann, alert to the implications, took great pains to ensure that the Zionist case was presented with the utmost cogency. As President of the Zionist Organization and of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, he delivered the opening statement on behalf of the Jews to the Royal Commission in Jerusalem on 25 November 1936. He subsequently gave evidence four times on camera, and directed the presentation of evidence by other Zionist witnesses and maintained informal contact with members of the Commission. With its departure from Palestine early in 1937, he could discern the rough outlines of the recommendations likely to be submitted to the Government. For on 8 January one of the Commission’s members, Professor Reginald Coupland, had broached to him the idea of dividing Palestine into two separate Arab and Jewish states.

Weizmann’s response was studiously non-committal. Palestine had already been partitioned to the detriment of the Jews, with the formation of Transjordan in 1921-22. As a solution partition ran contrary to the entire official Zionist position, which had stressed on numerous occasions the need for more vigorous application by the British authorities of the terms of the Mandate as ratified by the League of Nations in 1922. Zionist planning was predicated on the further development of the country under the aegis and protection of Great Britain; and now here was a far-reaching, almost revolutionary, proposal to abolish the Mandate completely. Finally, partition embodied the idea of Jewish statehood, a concept which few Zionists had hitherto dared to express publicly and even fewer considered practicable in the early future. Weizmann asked for more time, to consider the idea and to consult his colleagues.

However, he subsequently explored the proposal with Coupland at some length, aided by the use of maps. They had a private meeting at which all remaining doubts were dispelled, and in a burst of enthusiasm Weizmann was reported to have remarked that ‘we have laid the foundations of the Jewish State!’

He felt inspired by the prospect of Jewish sovereignty at last, but nothing could ease the heavy toll which strenuous activities and tension had taken of him, both physically and mentally, during the previous year. He was worn out. And on his return to London the air of uncertainty which he found there added to his anxieties. His experience with English politics and politicians taught him, above all, the value of caution. As a statesman who preferred to deal with realities rather than with abstractions and pious wishes, Weizmann appreciated just how fragile was the dream of statehood. For partition to succeed it would first have to be endorsed by the Government and then be enforced against the opposition of both anti-Zionists and maximalist Zionists. He therefore took nothing for granted in the safeguarding of what he saw as the movement’s best interests and in the encouragement of British leaders in the fateful decisions necessary.

It was vital to prepare Zionist strategy for any eventuality. In his public statements the Jewish leader continued to insist on strict adherence by Great Britain to its obligations, and to a full implementation of the Mandate. In private discussion, however, Weizmann expressed guarded optimism about a fundamental re-ordering of Anglo-Zionist relations. He travelled to Paris to meet Leon Blum in January 1937, coming away with the French Premier’s endorsement of partition and a Jewish State. And, availing himself of the delay in publication of the Royal- Commission’s report, he retreated to the Continent for some much-needed medical attention and rest. These were but brief interludes in Weizmann’s sustained activity for a favourable report. At a dinner given by Sir Archibald Sinclair on 8 June, he discussed partition with a number of prominent British figures, including Winston Churchill and Leopold Amery, both former Colonial Secretaries known for their support of Zionism. This gave him a foretaste of the difficulties which lay ahead. His dinner companions, with the exception of Amery, vigorously opposed the partition of Palestine, on the grounds that it would be unworkable and a betrayal of Zionism. Churchill insisted that the Jews should persevere with the Mandate as the only course.

Equally frustrating for Weizmann were parallel efforts at achieving a Jewish consensus in advance of the report. He argued within Zionist councils that partition, if implemented, would enable the Jews to embark on a great enterprise. Urging the immediate necessity of purchasing new tracts of land in Palestine, he explained how this would guarantee ‘a wide and still more extensive domain in Eretz-Israel. However, he found most Jews, even his fellow-Zionists, hesitant and divided over the prospects, implications and merits of a partition solution.

Small wonder, therefore, that the last days before publication of the long-awaited Peel Commission Report saw Weizmann tense. He assessed the situation as leaving everything in a state of suspended animation. ‘We are groping in the dark,’ he wrote to Stephen Wise in America. He was torn between the dangers of having Britain renounce its Mandate and the great appeal of Jewish self-government. He warned Wise of how essential it was that ‘we should all stand united, keep cool heads, and not burn our boats on either side.’

Finally, on 7 July, the months of speculation ended. The Peel Report, comprising 400 pages, was found, on balance, to be not unsatisfactory from the Zionist standpoint. While defining the nature, roots and causes of the enduring Palestine problem as a clash between Arab and Jewish nationalism, the Commission had been genuinely impressed by the manifold achievements registered in Palestine by the Zionist settlers. Weizmann could hardly have been unmoved at the praise expressed by so authoritative a body for Jewish endeavors in the economic, cultural and social revitalization of the Holy Land, and its acknowledgement that, in terms of history, the Jewish people had a legitimate claim to Palestine.

But so, according to the Peel Report, did the Arabs of Palestine. This basic situation of ‘a conflict of right with right,’ and with a widening of the gulf between the Arab and Jewish communities, led the Commission to conclude that the British Mandate was no longer workable. Despairing of effecting a reconciliation between the two national movements, each bent on complete sovereignty over all of Palestine, the report advised that ‘the only hope of a cure lies in a surgical operation:’ partition of the country into separate states.

Simultaneous with publication of the report, the Government issued a statement of intent, recording its ‘general agreement’ with the report’s arguments and conclusions. It described partition as ‘the best and most hopeful solution of the deadlock’ in Palestine, and proposed taking ‘such steps as are necessary and appropriate’ to implement the scheme.

For Weizmann, here at last was something concrete, an explicit British policy for Palestine. It now became possible, indeed crucial, to debate the partition proposal openly, to rally Jewish support and to formulate a specific course of action. And as a practical politician he knew he must apply all his influence to ensure that the Chamberlain Government carried out its declared policy, with the best territorial conditions obtainable for the Jewish State.

For more than a year Weizmann sought to close Jewish ranks while laboring to penetrate the innermost circles of policy-making in London. From July 1937, when partition first became a topic of serious public debate, until November 1938, when it was formally discredited and rejected by the Cabinet, he pursued these goals with more vigor than success.

The partition concept threatened to create a schism within the Jewish world reminiscent of the clash between supporters and opponents of the controversial East Africa (Uganda) scheme which occurred during the Seventh Zionist Congress, attended by Weizmann, in 1905. This time the debate took place at the Twentieth Congress, at Zurich in August 1937, shortly after publication of the Peel Report. Both Weizmann and the partition proposal were subjected to intense criticism, with opposition bringing together such disparate groups as the Mizrachi religious Zionists, who viewed the Biblical boundaries of Palestine as inviolate, and the Socialists of Hashomer Hatzair, who stressed the feasibility of Arab-Jewish working-class cooperation and who therefore found the spirit of partition retrograde.

This nucleus of Weinsagers,’ drawing supporters from the entire Zionist ideological spectrum, had its most determined advocate in Menahem Ussishkin, elder statesman of the movement and traditionally opposed to Weizmann’s leadership. In his view they were being asked either to consent to the strangulation of Zionism or to the shattering of Palestine into fragments. Ussishkin refused to accept these imposed alternatives, pointing to the strength of 17 million Jews who would oppose any plan, even if sponsored by the British Empire, which compromised the historical claim of their people to all of Palestine.

In one of the most moving and effective speeches of his career, Weizmann addressed the Congress on 4 August. In refutation of the charges against him, which went so far as to accuse him of having been originator of the partition idea, he distinguished between the ideal and reality. He had already intimated, a month earlier, that he was prepared to leave ‘the problems of expansion and extension to future generations,’ in the knowledge that the Jewish destiny to acquire Palestine undivided would be fulfilled someday. What concerned him, above all, was the present task; ever the scientist, Weizmann conceived partition as a ‘fulcrum on which to place a lever’ —a means for solving the Jewish problem.

He posed the central issue in the simplest terms. ‘The choice lies between a Jewish minority in the whole of Palestine,’ he told the Congress, ‘or a compact Jewish State in a part.’ Governing his preference for the latter was the deteriorating position of European Jewry. Consequently, in words full of emotion, he declared: ‘If the proposal opens a way, then I, who for some forty years have done all that in me lies, who have given my all to the movement, then I shall say Yes, and I trust that you will do likewise.’ At the conclusion of his speech most of the audience rose spontaneously to sing Hatikva, the Zionist anthem.

Supported by David Ben-Gurion, Moshe Shertok and Nahum Goldmann, Weizmann succeeded in carrying the day. Voting was 299 delegates in favor, 160 opposed and six abstaining on a resolution which read: ‘The Congress empowers the Executive to enter into negotiations with a view to ascertaining the precise terms of His Majesty’s Government for the proposed establishment of a Jewish State.’ This was hardly a ringing affirmation of partition, but the Zionist President regarded it as satisfactory; as he wrote to Bernard Joseph, it ‘at least gives us the opportunity to go on with the work.’ Thereafter he directed all his efforts upon an irresolute British Cabinet. Empowered to explore further the prospects of partition, Weizmann’s aim was to convince the British that imperial self-interest in fact demanded the establishment of a strong Jewish State.

In 1937 the broad outlines of an Italian thrust into the eastern Mediterranean and the Arab lands beyond, with the financial and diplomatic encouragement of Germany, could be discerned by British policy-makers. Since the early 1920s Great Britain, and to a lesser degree France, had exercised firm control over the former possessions of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, undisturbed by significant opposition from either the region’s inhabitants or any Great Power rival. As a result, British attitudes were marked by complacency and self-assurance, with a preference for stability rather than change.

By contrast, in the late 1930s there arose the possibility of a political convergence inimical to Britain’s vital Middle Eastern interests. Italian and German expansionism threatened to link with local Arab militants, whose discontent at the slow pace of independence tended to make them logical as well as desirable allies for the Axis Powers.

Mussolini’s brutal conquest of Abyssinia in 1936 gave Italy a position close to Egypt, the Suez Canal and the Arabian Peninsulaall clearly falling within Britain’s sphere of influence. Anti-British propaganda broadcast in Arabic from Bari, together with a diplomatic treaty with Yemen in 1937 and evidence of monetary aid and arms supplies to Arab extremists, served to reinforce British perceptions of a growing Middle Eastern threat. Germany’s parallel efforts at establishing ties with the Arab countries, co-ordinated from Baghdad by Dr. Fritz Grobba, tended to heighten such impressions.

Led by the Foreign Office, British opinion was reaching the conclusion that any Axis-Arab alliance could best be thwarted by appeasement. However, Weizmann and his colleagues put forward a counter-argument. A Jewish Palestine, linked by treaty to Great Britain, would be of immense political and strategic advantage to the latter. The yishuv would counter the Axis threat by retaining for Britain a vital regional presence in the eastern Mediterranean, and frustrate any such alliance between Germany, Italy and one or more of the Arab countries. British steadfastness, adoption of a firm policy of partition in Palestine—so the Zionists argued—would help immeasurably in restoring British prestige, which in Arab eyes had been damaged by indecision at the height of the Abyssinian crisis. Rather than alienating the Arabs, British resolve in Palestine would quickly make them realize that their natural ally was Great Britain and not the rapacious, authoritarian Axis Powers. In promoting his case Weizmann cultivated every social and political contact established painstakingly over the years since his Manchester days as an immigrant Russian chemist.

This difficult task was exacerbated by the fear permeating the ruling circles of Europe of a new global war. The atmosphere reached its peak with the crisis of Czechoslovakia and the Munich Pact in September 1938, and subordinated all other issues in the British mind. The future of Palestine was seen not on its merits but rather

in terms of larger concerns and interests. Thus Weizmann expressed himself as ‘overcome by grave anxiety about the fate of the West – after all we are so closely bound up with it.’ But little alternative existed for the Jewish people, whose fate was being weighed on the scales. We are ‘still too much of a plaything in their hands,’ he wrote in February 1938.

Further tying Weizmann’s hands in negotiations with the British over specific details of partition were the many difficulties encountered in concerting Jewish efforts and activities. In his dealings with European heads of government Weizmann sought to project an image of himself as the sole spokesman of the entire Zionist movement, if not of the Jewish people as a whole. Yet such unity was a myth. In reality, the Jewish people in 1937-38 were deeply divided over Zionism, and a number of challengers to Weizmann’s position and authority had arisen. The partition controversy merely emphasized this situation.

Weizmann’s political activities and the work of the Jewish Agency were being hampered by strained relations between the Agency’s Zionist members and those, represented by Felix Warburg of America, who were non-Zionist yet concerned in strengthening the yishuv in Palestine. The latter alleged discrimination against them within representative bodies of the Agency and held over Weizmann the threat of resignation unless given satisfaction on their various demands. Weizmann was compelled to dissipate much of his energies in patching up these differences.

A second challenge came from within Zionist ranks. Some of those still loyal to Weizmann disagreed with his pro-partition policy. Others, among them Judah Magnes, President of the Hebrew University, and Lord Samuel, High Commissioner for Palestine in 1920-25, were outside the official Zionist structure and continued to fight partition despite the majority vote at Zurich. Their opposition took the form of initiatives, not always coordinated with the Zionist Executive, aimed at circumventing the Mandatory Power and nullifying any need for partition. This, they felt, could be done by entering into immediate, direct talks with Palestinian and other Arab representatives.

Weizmann took particular offense at these unilateral moves. He regarded them as both undermining his authority and as indirect criticism of his previous efforts at an Arab-Jewish rapprochement. Of Magnes and his followers, he wrote defensively to Warburg: `Everyone agrees as to the necessity of some agreement with the Arabs, but no one can suggest how best to set about getting it.’

He encountered still another form of Jewish opposition. At a particularly crucial phase of the partition debate, leading Anglo-Jewish communal figures intervened against the partition policy. Lord Reading, Sir Osmond d’Avigdor-Goldsmid and Lionel Cohen, all of them non-Zionist members of the Jewish Agency’s Political Advisory Committee, submitted a memorandum to the Foreign Office raising objections to Jewish statehood. Pointing out that `over-exaltation of racial and national feeling is at the root of the world’s troubles,’ they urged Arab-Jewish negotiations as an alternative to partition. Weizmann treated these assimilationist Jews with scorn. He assured Sir John Shuckburgh, a Colonial Office servant hitherto not unsympathetic to Zionism, that ‘on a momentous problem like Palestine their voice will not carry beyond their own narrow circle of the gilded ghetto in which they live and prosper.’ But this could not erase the impression in British circles that world Jewry was sharply divided over Jewish statehood. If so, the argument by British opponents went, why should Great Britain commit itself to anything as controversial and politically costly as partition?

Yet another group harassing Weizmann during this period were the extremist Zionists, led by Vladimir Jabotinsky and his Revisionists. Bitterly opposed to sharing Palestine with the Arabs, they insisted, on the contrary, that Palestine on both sides of the River Jordan should become the Jewish State. Jabotinsky’s activities prompted Weizmann to describe him as possessing ‘an ardent de sire to be a leader in Israel (though Israel does not seem too keen).’

Weizmann was worried at this time also by a parallel growth in militancy on the part of his younger Palestinian associates, such as Ben-Gurion. They were increasingly to question his policy guidelines, particularly his advancement of the Zionist cause through collaboration with Great Britain. Under the combined weight of this suspicion and criticism, Weizmann’s resolve began to waver perceptibly. His letters indicate both a sense of isolation and a drift into moods of depression.

Always reserved, and aloof except to a select few of his Zionist colleagues, Weizmann pours out his feelings mainly in letters to certain female correspondents: his wife primarily, and then Ivy Paterson, Blanche (`Baffy’) Dugdale, his secretary Doris May, his friend Lola Hahn-Warburg. It may be said of the ageing Weizmann in this trying period that maintaining his extensive correspondence became a psychological outlet which ‘relieves my inner pressure somewhat.’ His fits of depression alternated with moments of exhilaration, and he was wont to question his powers of endurance.

In March 1938 Weizmann reflected that ‘these last three weeks in – London have been the hardest in my life.’ Nevertheless, he was planning an immediate return to Palestine, ‘and Palestine makes everything worth while.’ Towards the end of the year his spirit rose considerably. To his family in Haifa he wrote: ‘I have lived and am living through difficult days, but for the first time I see a glimmer of light.’ But this hope was not destined to last. He was maintaining a heavy and intense schedule only infrequently relieved by brief periods of rest and relaxation. The Zionist movement was facing a decisive moment in its history with the struggle over partition, and Weizmann’s anxieties were heightened by Nazism and other expressions of antisemitism in Europe. Contesting the future of Palestine, building the yishuv and striving for statehood would have been more than sufficient challenge even for a man of Weizmann’s exceptional energies and capability. At least these goals offered inspiration, a vision of a brighter future for his people. But with the loss of enthusiasm in British circles for the partition policy towards the close of 1938 the entire emphasis of his work became defensive, on the Continent no less than in London and Palestine. Priorities tended to shift drastically, in line with the quickening pace of world events.

Following the Nuremberg Decrees, discriminatory legislation in Germany systematically deprived the Jews there of their rights, property and human dignity. In 1938 Germany’s annexation of Austria, indicating the likelihood of additional Nazi expansionism, also suggested that German antisemitism would spread into the not infertile soil of the neighboring countries of Central and Eastern Europe. No less ominous, from Weizmann’s perspective, was the 1938 Munich Pact, signed by Germany and Great Britain. It signaled that any Jewish hopes for a united front against Nazism led by Britain and France, as a means of saving European Jewry, were wholly misplaced. Hence, Weizmann threw himself into the urgent task of holding European Jewry together, and of salvaging as many Jewish lives as possible from the advancing holocaust. His leadership of a divided movement, his vulnerability to personal attacks, did not lighten the burden. His vain efforts at combatting British inaction over Palestine, his declining health, and his worries as a son, brother, husband and father, all took their toll.

Weizmann’s responsibilities as head of a family seem to have been especially painful to him in 1937-38. In particular, he was disappointed at the progress of his two sons, Benjamin and Michael, and at his own inability to communicate with them or guide their careers. Indeed, in a letter to his mother on 15 January 1937, the elder son, Benjamin, warned: ‘it is high time this family was taken in hand by somebody; otherwise, the Jews may have a National Home but we shall have none at all.’ That Weizmann also sensed this is indicated by a letter to his wife in November 1937, in which he confessed: ‘Perhaps it is being borne upon me that I have neglected my own small family for the sake of the larger one which I have been trying to serve so faithfully.’

As a result of his almost daily contacts with British policy-makers in Downing Street and Whitehall, reinforced by reports from Jerusalem, Weizmann detected by the autumn of 1937 that, despite his efforts, the idea of partition was losing its momentum. In July both Houses of Parliament expressed grave reservations at the Government’s intended course of action. And in September the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations openly questioned British intentions in Palestine. Compounded with this, world Jewry’s reaction was at best lukewarm, and the Palestinian Arab community, led by the Mufti of Jerusalem, was united in opposition to partition. Furthermore, in a significant development during this period, the neighbouring Arab countries—Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia and Transjordan—each began to assert its diplomatic influence with Great Britain in favour of the Palestinian Arab cause and in opposition to partition and Zionism. Consequently, with the Eastern Department of the Foreign Office afraid of alienating the Arab world at a time of international crisis, the Government began to turn away from its declared policy as recommended by the Peel Commission.

The first step in this reversal was the announcement in December 1937 of the Government’s intention to send a Technical Commission to Palestine, with Sir John Woodhead as chairman, for the ostensible purpose of devising a detailed plan of partition. Privately, the Cabinet had already resolved to abandon the scheme. Hastening back to London from his home in Rehovot in January 1938, No. 280 Weizmann expressed his concern to d’Avigdor-Goldsmid. ‘What is urgently required in Palestine now,’ he wrote, ‘is a definite policy, and a speedy decision.’ Reinforcing his unease were reports from Palestine of deterioration in public security and renewed acts of violence against the yishuv by Arabs.

The Woodhead Commission arrived in Palestine in May 1938. Its final report, publicly stating partition to be inappropriate in Palestine, was released only in November. Lest Jewish opponents of partition become elated, Weizmann had already warned at least a year earlier of the even less favourable alternatives. With notable prescience he cautioned Wise in October 1937 that the failure of partition ‘does not mean a return to the Mandatory regime but to something infinitely worse from our point of view.’

In place of partition the Government invited Arab and Jewish delegations to London in order for them to work out a compromise to the Palestine problem under British auspices. The year 1938 thus terminated politically for Weizmann with his preparations, however dispirited and sceptical, for what became the two parallel St. James’s Conferences. These negotiations were to lead to the 1939 White Paper, to Britain’s abandonment of its pledges to the Jewish people in the Balfour Declaration, and hence to the greatest political disappointment and setback suffered by Weizmann in his long career as Zionist statesman.

Meanwhile, Weizmarth the scientist continued to take a close interest in the Daniel Sieff Research Institute at Rehovot. He directed the research efforts of its growing scientific staff, dealt with their personal problems, conducted experiments aimed at strengthening the yishuv’s industrial potential, and labored at putting the Institute on a sound financial footing. Given his involvement at the time with life-and-death matters for Zionism, how incongruous it is to ‘find him required also to decide such matters as the exact Hebrew spelling of a memorial plaque!’

Attesting to the diversity of his interests are his letters concerned with the Agricultural Station, also at Rehovot, with the affairs of the Hebrew University and in particular its Faculty of Science of which he was Dean, with the Jewish National Fund, with libraries and the theatre in Palestine, and with the pioneering settlements.

These efforts stemmed from his passionate interest in developing Jewish life in Palestine. In extending an invitation to Professor Albert Einstein to lecture at Jerusalem, Weizmann argued that this would represent ‘a tremendous moral strengthening for the yishuv.’ An industrial base, land purchases, a Jewish fighting force—all of these demonstrated his conviction that the Zionist objectives could only be fulfilled, British support or no, through tangible accomplishments, creating facts and Jewish self-help.

The link between Zionism and the Jewish people as a whole led to yet another responsibility for Weizmann, which was also a privilege—that of representing world Jewry before international forums, and of being the intermediary between the scattered Jewish communities of the Diaspora. By 1938 this role was becoming pressing in light of events in Europe; to Mrs. Dugdale Weizmann wrote: ‘Part of us will be destroyed and on their bones New Judea may arise!’ Much of this sense of foreboding came from Weizmann’s struggle to alert passive European opinion with pleas on behalf of persecuted Jews. After a futile effort to gain British consent for the entry of 2,000 children into Palestine, he wrote bitterly to the Colonial Secretary, Malcolm MacDonald: ‘Here we reach a limit at which human feelings are outraged beyond measure.’ Unfortunately, as he was shortly to realize himself, these limits had by no means been reached as yet.

Under pressure of all these responsibilities, Weizmann was compelled to postpone a project dear to him, the writing of his memoirs. He had signed a contract in March 1938 with the Harper publishing house, and worked sporadically. In the end, publication of his memoirs had to be suspended.

He undertook a journey to Istanbul in November 1938, primarily to persuade the Turkish Government to use its good offices as an intermediary between the Zionists and the Arabs. The initiative had conic from the Turks who, seeing in Weizmann the head of world Jewry, were anxious to secure a substantial loan from Jewish banking firms in order to cover a growing budgetary deficit. Yet another motivation for the mission derived from the sense of loyalty Weizmann still retained toward Great Britain as guardian of the Jewish National Home. Therefore, he was urged by British leaders to utilize his talks in Istanbul for purposes of probing intentions toward Britain in the event of war, and in counter-acting Axis influence in Turkey.

Just as this visit to Turkey offers a glimpse of Weizmann in his many roles, so, too, does its outcome serve as epilogue to the years 1937-38, and to the entire inter-war period of his career. For the mission produced no tangible accomplishment, and merely reinforced his general feeling of impotence in shaping events. ‘A new leader should arise in Israel now who should sound the call,’ he wrote to Mrs. Dugdale, ‘we are already old and used up.’

The world on the eve of the New Year, 1939, was edging towards war. The Jewish people were in a state of virtual helplessness, and the flames of Kristallnacht on 9-10 November foreshadowed the greater tragedies to come. The yishuv in Palestine, but a few months earlier on the threshold of statehood, was now threatened with a freeze in its development, and permanent minority status.

Weizmann, whose life had long been bound up inextricably with the Zionist idea, moved in 1937-38 from hope to desperation. Justifying his faith in Great Britain, expressing his Jewishness, waging his struggle on behalf of Zionism—each of these by the close of 1938 was becoming for him an ordeal. And yet he continued to believe

that ‘all these hopes, labours and sufferings were not and cannot be in vain.’ Facing the unknown, his powers diminished, Weizmann still retained that sense of messianic hope which was to sustain him during 1939 and through the subsequent years of war, tragedy and triumph.

AARON S. KLIEMAN