The Census of Palestine, 1931 – An Invaluable Glimpse at Palestine’s Population: Gaping Socio-Economic Distances and Differences between Muslims, Christians, and Jews

Compilation Ken Stein, July 12, 2021

The 1931 Census of Palestine is a wonderfully rich and essential review of Palestine’s population on November 18, 1931. We learn that the Arab and Jewish communities were only not equal in size, which we knew, but they were dramatically different in levels of literacy, residential preferences, occupations, and more. By 1931, the communal socio-economic divide was vast and it would get wider and unbridgeable in so many ways, leading in part to the suggested physical partition into Arab and Jewish states in 1937.

The Census is an extraordinary compilation of facts with truly unbiased analyses of what changed in Palestine since the end of WWI and the advent forward of the British military and civilian administrations. The analyses in the Census made multiple useful comparisons to other contemporary populations in the Middle East, Europe and elsewhere. For Palestine, there was a far less complete census made in 1922 and another for a handful of villages in 1945.

Careful reading of the three volumes permits a thorough understanding about how the various populations were not only numerically different, but by the early 1930s sociologically, geographically, and economically distant from one another. As of November 18, 1931 there were 1,035,154 persons in Palestine, 80% of them (759,712) Muslims, 17% Jews (174,610 doubling its size since 1922 (83,794 then), with Druzes in 1931 number 9,148 (increasing some 2000 since 1922); Christians numbering 91,338 (increasing from 73,024 in 1922). Of the Christian population 86% were of Palestinian citizenship. There were over “440,000 persons supported by ordinary cultivation of whom 108,765 were earners and 331,319 were dependents. Of the earners 5,311 derived their livelihood from the rents of agricultural land, 63,190 persons cultivating their own land in whole or in part or cultivating lands which they hold as tenants. The vast majority of this cultivating or rural population, 64% were Moslem Arab. The agricultural population was taken to consist of rent-receivers, actual farmers engaged in ordinary cultivation, and agricultural laborers. The earners in this population numbered 108,376 and of these earners 26,240 or 24.2 percent have returned a subsidiary occupation.” Thus with irrefutable evidence from other Arabic, English, and Hebrew sources, we know that the vast majority of the Arab population in Palestine in 1931 lived at bare subsistence levels. And we know that for the next five years prior to the Arab rebellion or revolt in Palestine against the Zionists, the British and against some Arab notables, the rural economy went into successive years of decline. The Census refers to this population as “indifferent,” while other British (Colonial Office) sources and Zionist sources categorize the Arab rural population as “sullen.” We learn that Jews and Arabs lived distinctly apart from one another except for a couple of mixed towns like Jerusalem, Haifa, Tiberias, Safed, and others. Due to the British administration and Jewish development, the Arab death rates in Palestine dropped dramatically since the end of WWI, in comparison to other Arab areas in the Middle East at the same time.

Summary conclusions on age and origin of the populations

(i) Moslem -Population growing younger: not affected to a marked extent by migration

(ii) Jews – Population affected greatly by immigration in the ages 15-35 years: longevity greater than that of the Moslems.

(iii) Christians -Population affected by special types of immigration reducing the reproductive capacity of the community as a whole; comparatively great longevity.

Summary conclusions as to the nature of the educational problems of the future: –

(i) The problem of Moslem education is the provision of greatly increased facilities for primary education and an extension of the means for educating the younger females.

(ii) The problem for the Christian community is the provision of means for gradually extending the present facilities.

(iii) The problem for the Jewish community is the maintenance of the present high standards of primary education, and the creation of extended facilities for educating the members, particularly the female members, of the communities of eastern Jews.

Summary conclusion that joint land tenure and joint land use result undertaken in 65% of Palestine, primarily by the Arab rural population is debilitating and highly inefficient.

One of the most important factors contributing to the indifferent character of ordinary cultivation as practiced by Arab agriculturists has been the system of tenure known as mesha’a. Under this system relatively large groups of persons hold cultivable land in personal shares in undivided ownership, and each owner changes his holding at regular periods which very with different localities. As a general rule, occupancy of a specific holding changes once in two years. This primitive tenure is, of course, not peculiar to Palestine: the theory of the tenure seems to be that the group of co-owners have common dominion over the whole land, each owner receiving as his holding the amount of land corresponding to his undivided interests of ownership; but, in order to assure equality of treatment to all co-owners, so that all have the same chance of good and bad land over a course of years, the occupancies are varied in rotation at stated periods. It is not difficult to believe that such a system of tenure is a democratic expression of the benevolence of a patriarchal system of social organization characteristic of eastern peoples. It will be comprehended that it is a system that is disastrous to efficient agriculture. The cultivator cannot, in such a system, develop his temporary holding because, if he does so, some other co-owner will later reap the fruits of his enterprise. In these circumstances it is satisfactory to learn that the system, once fundamental in the organization of the social group of the village, is rapidly breaking down by the voluntary agreement of the various co-owners: and it may be anticipated that the standard of cultivation will rapidly improve, particularly if it be found possible to provide the means by which cultivators can obtain capital on fairly easy terms.

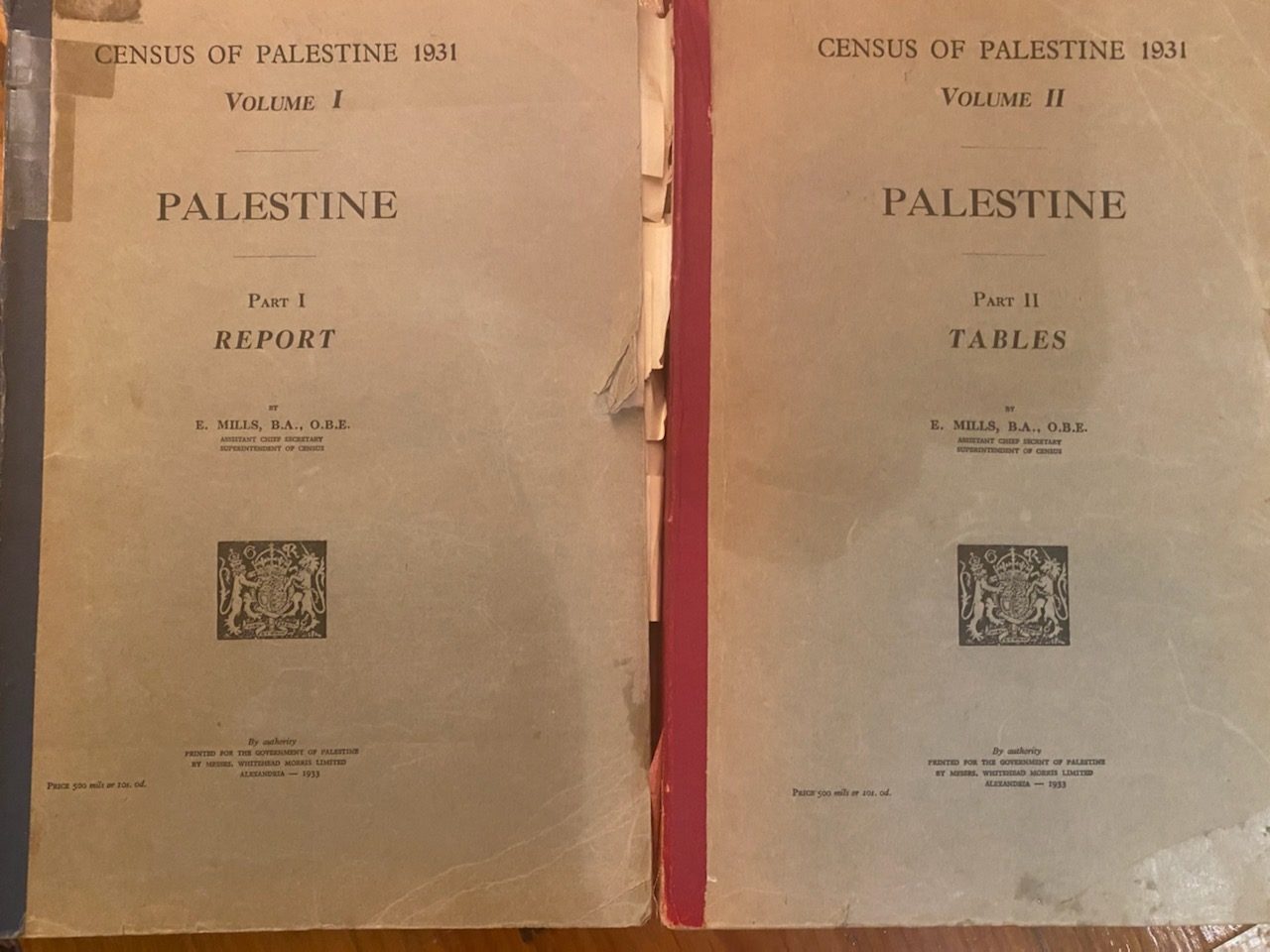

A note on the 1931 Census: It was produced in three volumes, the first is a narrative, the second contained tabulations, charts, maps, and mathematical analyses. The first volume is 350 pages, the second some 600 pages. The third was titled, “Population of Villages, Towns, and Administrative areas.” The third volume of 106 pages is the most detailed enumeration of Palestine’s population by village and towns we have for the entire Mandate period, broken down for each residential zone and for the bedouin by religion, sex, and number of homes. The Census was carried out primarily in the last several months of 1931, closed to additional collection of information on November 18, 1931. More than detailing the demographic features or the communities residing in Palestine at the time, the Census is a gold mine of data about literacy, religious affiliation, population distribution, occupations, deaths, birth rates, etc. It was published in bound volumes in 1932 and 1933. Below are only a dozen pages extracted from the more than 1,000 pages that made up the three volumes – Volume I of the Census: The Report of conclusions is available in pdf format at https://ecf.org.il/media_items/1090 . What appears here are only highlights and preliminary conclusions.

Population –General

The population enumerated as at midnight on the 18th of November, 1931, consisted of 1,035,821 persons of whom 66,553 were enumerated under the special system adopted for nomads (bedouin). The provisional total, declared within 20 hours of the enumeration, was 1,035,154 persons. There was thus an error of only 0.06 per cent, on the correct total. The Moslems number 759,712, of whom 4,100 are Shi’as; Jews 174,610 (increasing from 83,794 in 1922, now numbering 17% of the total population ); Druzes 9,148 (increasing some 2000 since 1922); Christians number 91,338 (increasing from 73,024 in 1922). Of the Christian population 86% are of Palestinian citizenship, pp.25-26)

Indeed only four towns have any likeness to urban centers as these are understood in Europe. These towns are Jerusalem, Jaffa, Tel Aviv and Haifa. Of the remainder Nablus has a special claim to consideration on account of its parochial character in history, some of the social consequences of which are worth investigation. The remaining towns can only be described as convenient centers for the marketing of rural products, or as large villages. Practically every group of persons dwelling in one area and numbering over five thousand was constituted a municipality. Arbitrariness in social and administrative arrangements is a consequence of the logical determinism of an administrative code not related to the social circumstances to which it is applied. To differentiate between urban and rural populations it is necessary, therefore, to add the arbitrariness of selective judgment to the arbitrariness originating in legal determinism, if social phenomena are to be presented in a proper light.

No specific definition was given for village, but instructions were issued that, where that definition could not be applied then the residential unit was t be adopted as the village. The conception of a village seems clear enough, but it is, on examination, complicated when precision of statistics is required. There is, as a general rule, no difficulty in Palestine in recognizing in a general way the residential unit. The history of the country has led to the construction of villages in compact masses of structures. The village lands, in theory at any rate, lie around the villages, and the system of land registration, introduced in the years before the war, recognized the theoretical simplicity of these social arrangements by recording mutations in interest in land in annual registers associated with each sub-district. Without entering the difficult question of land tenures in Palestine, it is enough to say that, as a result of a vicious system of registration by names of persons holding interest in land, “islands” of land in one village became part of the lands of another village. The result is that the complete territorial description of a village would lead, in many instances, to complete confusion in a census record. Hence it was essential to fall back on the residential unit as the village, if the prime definition were likely to lead to confusion. Another difficulty made this arrangement necessary. Jewish settlers have sometimes acquired land within the boundaries of an existing village, and have constructed their own village upon their property. The land which they acquired is, however, still part of the territorial lands of the original and existing village: the personal interests have changed, but the land itself remains within the confines of the transferor village regarded as a territorial unit. In such cases it was eminently desirable to treat the two residential units, if they were large enough, as two census units; or the smaller as a dependent unit with its own identity in the larger unit. To have insisted on the prime definition of village would have led to complete loss of individual identity of one of the two units which, in every social sense, were two distinct entities. Homesteads according to their size and number were regarded as either integral parts of the territorial village or were tabulated as “attached hamlets” thus preserving their identity although not tabulated as separate villages. It will be appreciated, therefore, that the structure of the conception of “village” is, under analysis, far from simple and, for census purposes, much elaborate care is required if precision is to be given to the statistics of census.

TOWNS

Regarding Palestine as a whole, 41 percent of the population resides in towns and 59 percent in villages. In the Southern district 51 percent of the population reside in towns: in the Jerusalem district 49 percent, and in the Northern district 29 percent. Although the Northern district has a larger number of towns in the sense of municipalities than the other two districts, these towns apart from Haifa are small and exhibit practically no urban features. As was to be expected in a small sub-district with two towns, both of urban character, Jaffa sub-district gives an urban population of 72 percent of its settled population. In Jerusalem sub-district 69 percent reside in the towns, and in Haifa sub-district 57 percent. If regard be had to the total population, including the nomads, these proportions are reduced in the Southern and Jerusalem districts, and the Jerusalem sub-district has the highest percentage of urban population(68 percent), the Jaffa sub-district taking second place with an urban population forming 67 percent of the total population of the sub-district. The statistics by religious confession for the total population show interesting variations. In Palestine as a whole 25 percent of the Moslems live in towns, so that at least three quarters of the Moslem population follow rural occupations; 74 percent of the Jews live in towns and 76 percent of the Christians, so that only about one quarter of each of these communities can be assigned to the rural populations. A not negligible proportion of the Christian community consists of Europeans in His Majesty’s Forces, in the public service, and in the consular services, a great proportion of whom reside in towns, thus inflating the urban population of Christians. In the districts 90 percent of the Christians in the Southern district live in towns and in the Jerusalem district 94 percent of the Jews are town dwellers. The Northern district shows considerably higher proportions of rural population for all communities, 59 percent of the Jews living in towns, 64 percent of the Christians and 21 percent of the Moslems. (pp.50-51)

In order to interpret these statistics it is well to keep in mind the main causes affecting the movement of population in the natural divisions. Broadly speaking, changes in the maritime Plain are due to natural increase and immigration: changes in the central Range are due to natural increase, immigration being a negligible feature except in Jerusalem Town; changes in Esdraelon and Emek are due to natural increase and immigration: changes in Galilee are due to natural increase and additions to populations by transfer from Syria.

In 1922 the rural population of the Maritime Plain was 31 percent of the total rural population: in 1931 it was 37 percent. The Central Range accommodated nearly 37 percent of the rural population in 1922, and in 1931 nearly 36 percent. The rural population of the Maritime Plain increased during the intercensal period by nearly 52 percent, while that of the Central Range by less than 25 percent. Now the rural population of the Central Range is to all intents and purposes Arab, mostly Moslem but in very small part Christian, and, if there were no cause of change other than natural increase, there is a legitimate expectation of an increase of about 28 percent during the intercensal period. Since the increase in the Central Range is only 25 percent, the inference may be drawn that emigration from the Central Range has taken place. Now, it is known that there is Christian emigration from Ramallah and Bethlehem to other countries; this emigration is of importance to the very small populations from which the emigrants are drawn, but is insignificant in relation to the total population of the Central Range (373,000 persons). It is also known that the number of Moslem emigrants is so small as to be negligible. Consequently it may be concluded that emigration from the Central Range is almost entirely to other parts of Palestine. The relatively small intercensal increase in Esdraelon and Emek (19.6 percent) rules out, in all probability, the possibility of significant movement from the Central Range to that natural division; the increase in Galilee is about the same as that of the natural population if allowance be made for the increase due to transfer of population from Syria; it follows that the emigration from the Central Range is towards the Maritime Plain. This is in complete obedience to economic laws: development attracts productive labor from areas where development is not anticipated, or where livelihood is stationary.

The movement from the Central Range is, of course, in part due to the increasing density of population. In 1922 there were in this division 41 persons per square kilometer, in 1931 the number had risen to 51; but the density in the Maritime Plain had increased during the same period from 52 to 78 persons per square kilometer. That is, in the former case the density had increased by 25 percent, and in the latter by 50 percent. No doubt the soil of the Maritime Plain is more fruitful or fructifiable than that of the Central Range; it has also been shown that the proportion of cultivable land is very much greater in the Maritime Plain than in the Central Range; but these features are also features of Esdraelon and Emek, where the increase in density per square kilometer is not as high as 25 percent. It is, therefore, legitimate to infer that development is the main attraction of emigration from the Central Range, and that the closer “packing” of the population in the Maritime Plain, so far from driving people away either from Palestine or to the other parts of Palestine, has had the effect of attracting people from the hill country and so relieving the population and soil pressures in that area. (end p.51)

General Concluding Observation

In so far as growth of population is a measure of prosperity the past decade is witness to the effects of British administration on a population depressed by the lack of initiative characteristic of the pre-war Ottoman Empire. That this depression had not devitalized the people is clear from the remarkable natural increase of the population. That this remarkable increase is concomitant with an increase due to an effective immigration from outside Palestine is perhaps an indication that the two movements are not uncorrelated. This immigration itself stimulates production and a more effective utilization of natural resources so that a larger population may be supported; and associated with this immigration is an import of valuable commodity by means of which the population as a whole has enlarged its capacity of purchase, and consequently, it prospects of supporting its own growth. On the other side, the experience of the world shows that this process is not capable of indefinite extension in time; and, within a future that is measurable, there will be required in Palestine a much greater rate of growth of production, and a much more intense utilization of natural resources combined with invisible import of value if the present dual process in the growth of the population is to continue. (p.52)

Religion: The Importance of Palestine in the world of Religion (p.78)

It is impossible to include within the limits of a chapter of this Report even the barest outlines of the history of religion in Syria and Palestine; and the most that may be attempted is to mark the supreme influence of Palestine in the world as a consequence of that history. The three great Semitic religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, to name them in the order of the history of their emergence, have played and continue to play incalculable parts in the activities of the whole world, these activities touching or embracing entirely every phase of life individual or social. Judaism and Christianity are both indissolubly bound to Palestine, in the case of the latter in virtue of the history of its origin, and in the case of the former, in virtue of this early development in maturation. Islam, in its syncretistic character, is bound to Palestine, or at least to Jerusalem, as being the venerated cradle of both Judaism and Christianity. These three confessions have acted, reacted and interacted in a manner which, through Judaism and Christianity, links the world in historical and religious associations to a Palestine and a Syria as these countries were long before Judaism and Christianity had emerged as distinct creations; and which, through Islam, renovated the life of Europe, making possible the utilization of learning that would otherwise have been lost to mankind, and making civilization the supreme end of living.

The Mystery Religions, found in the countries bordering the Eastern Mediterranean earlier than or coexisting with Judaism and Christianity, contributed to the world the notions of divine powers controlling the natural order and communion with the god which, combined with the drama of the seasons, led to ideas of resurrection of the individual and the hope of future life. Judaism, with its stern monotheism, refused all compromise with the polytheistic conceptions of the neighboring peoples; and the prophetical books, with their exhortations, rebukes and combinations, show how bitter was the struggle between the intellectualism and austere discipline of monotheism and the natural response of natural man, not especially primitive to the incomprehensible workings of the world in which he lived. Christianity, with a subtle alchemy, blended the monotheism of the one with the satisfying ritual notions of the other, and sought to combine in one perfect whole the complete activity of individual man in his earthward and God-ward aspects. But, more than that, the fabric of both Judaism and Christianity is shot with the stuff of philosophies, which still remain, for many, the most valuable contributions of human thought and endeavor, and which still edify, refresh and support countless believers.

It is impossible, however to interpret the resultant effects of the development of Judaism and Christianity on Europe merely in terms of formal religious and philosophies: behind both was to be found the deep current of more primitive heathen rituals and beliefs mingled with the sacrificial ideas which are found both in the beliefs and in some of the Hebrew rites set forth in the Old Testament. In trying to understand the early development of Christianity this undercurrent of primitive and eastern ideas must not be ignored. (p.78)

The General features of the Religious distribution (p. 80)

The following table shows the distribution by main religious confessions of the population of Palestine in 1931 and 1922 together with the variation in each religious confession during the intercensal period: –

Religious Confession Number percent in Increase percent

1931 1922 1922-1931

Moslems … … 73.34 78.04 28.6

Jews … … … 16.86 11.07 108.4

Christians … … 8.82 9.64 25.2

Other confessions … 0.98 1.25 0.7

As to be expected, the increase in the Jewish community during the years 1922-1931 has augmented the proportion of Jews in the total population in such degree that the proportions of all other religious communities have diminished. The change in the proportional distribution as in 1922 and in 1931 is illustrated in Diagram No. 10. The distribution in the districts, given in detail in Subsidiary Tables I and II shows larger variations according to the weight of Jewish immigration into the various localities. The present distribution is illustrated in Diagram No. 11, where the widths of the rectangles are proportional to the total populations of the several districts. The area of each rectangle is, therefore, representative of the total population of the district, and, the heights of the partial rectangles being representative of the proportions of the population in the main religious confessions in the districts, each partial rectangle is representative of the absolute magnitude of the population of the religious confession to which it refers. The changes in distribution since 1922 are most marked in the Southern district where the Jewish proportion has increased from nearly 11 percent to nearly 22 percent, that is, has been doubled.

THE MOSLEMS

The Moslems number 759,712 persons of whom 4,100 are Shi’as. That is to say that the great majority of the Moslems of Palestine are orthodox – Sunnis, so-called because they observe the Sunnahs, that is, precedents or traditions. Sunni Moslems have four great schools of law named after their four founders. These four schools are the Shafi, named after Muhammad ibn Idris al Shafi’I; the Hanbali, named after ibn Hanbal; the Hanafi, named after Abu Hanifa; and the Maliki, named after Malik. There is a fifth school, that of the Ibadites in Oman and at Mzab in the Shara, which is the oldest of the schools, but which has the least influence, and is not represented in Palestine. It is stated that these four schools are represented in Palestine in the following proportions: –

Shafi … … 70 percent

Hanbali … 19 percent

Hanafi … … 10 percent

Maliki … … 1 percent

THE DRUZES

The Druzes come nearest in outlook and habit of life to the Moslems and particularly to the Shi’a elements.

Dr. P.K. Hitti begins his fascinating little study of the Druzes with the following sentence: –

“The Druzes of Syria and the Samaritans of Palestine are two unique communities not to be found elsewhere in the whole world. Like social fossils in an alien environment, these two peoples have survived for hundreds of years in that land rightly described a Babel of tongues’ and a museum of nationalities.”

The Druzes in Palestine number 9,148 persons: but the total Druze population must be about 120,000 persons so that the Druze population in Palestine is only a small fraction of the polity identified as Druze in its “national” – religious aspect. Their origin is obscure. They themselves claim to be Arab in origin; but the principle of dissimulation, adopted from Shi’a precepts on the basis of Koranic prescriptions, makes the Druze accounts of their origin unreliable.

In summary, it may be said that Druzes are probably Persian in racial origin; that their religion is at best, imperfectly apprehended; but that study of that religion throws additional light on early Shi’a sectarian beliefs and on certain Gnostic rites.

The Druzes enumerated in Palestine as the census 1931 number 9,148 and have increased by over 2,000 persons since the census taken in 1922. Males and females are equal in number; there is no doubt that they form a very fertile group. They are practically all tillers of the soil and their standard of life is perceptibly higher than that of the average Moslem peasants. ( p.85)

Subsidiary Table No. IV

Distribution of Christians by locality.

Number of Persons and Variation 1922-1931

| District and Sub-District | Actual numbers of Christians in | Variation percent 1922-1931 Decrease (-) | |

| 1931 | 1922 | ||

| Palestine | 91,398 | 73,024 | 25 |

| Southern District | 15,155 | 12,079 | 25 |

| Gaza Sub-district | 897 | 812 | 10 |

| Beersheba Sub-district | 153 | 235 | -35 |

| Jaffa Sub-district | 9,921 | 7,275 | 36 |

| Ramle Sub-district | 4,184 | 3,757 | 11 |

| Jerusalem District | 38,488 | 31,726 | 21 |

| Hebron Sub-district | 124 | 73 | 70 |

| Bethlehem Sub-district | 10,628 | 10,183 | 4 |

| Jerusalem Sub-district | 20,309 | 15,496 | 31 |

| Jericho Sub-district | 263 | 144 | 83 |

| Ramallah Sub-district | 7, 164 | 5,830 | 23 |

| Northern District | 37,755 | 29,219 | 29 |

| Tulkarm Sub-district | 356 | 263 | 35 |

| Nablus Sub-district | 1,214 | 1,085 | 12 |

| Jenin Sub-district | 851 | 661 | 29 |

| Nazareth Sub-district | 7,384 | 7,043 | 5 |

| Beisan Sub-district | 477 | 297 | 61 |

| Tiberias Sub-district | 1,734 | 1,316 | 32 |

| Haifa Sub-district | 16,492 | 11,107 | 48 |

| Acre Sub-district | 7,672 | 6,194 | 24 |

| Safad Sub-district | 1,575 | 1,253 | 26 |

Subsidiary Table No. V

Christian Population by Churches (p.98)

| Christian Churches | Total | Palestinians | Other than Palestinian | ||||||

| Persons | Males | Females | Persons | Males | Females | Persons | Males | Females | |

| Total | 91,398 | 45,896 | 45,502 | 78,291 | 38,031 | 40,260 | 13,107 | 7,865 | 5,242 |

| Orthodox Church of Jerusalem | 39,727 | 19,565 | 20,162 | 37,703 | 18,718 | 18,985 | 2,024 | 874 | 1,177 |

| Syrian Orthodox (Jacobite) | 1,042 | 582 | 460 | 921 | 491 | 430 | 121 | 91 | 30 |

| Roman Catholic: | 35,578 | 17,083 | 18,495 | 31,491 | 14,737 | 16,754 | 4,087 | 2,346 | 1,741 |

| a) Latin | 18,895 | 8,714 | 10,181 | 15,728 | 6,912 | 8,816 | 3,167 | 1,802 | 1,365 |

| b) Uniate Churches1 | 16,683 | 8,369 | 8,314 | 15,763 | 7,825 | 7,938 | 920 | 544 | 376 |

| Melkite (Greek Catholic) | 12,645 | 6,289 | 6,356 | 12,347 | 6,145 | 6,202 | 298 | 144 | 154 |

| Maronite | 3,431 | 1,738 | 1,693 | 3,036 | 1,504 | 1,532 | 395 | 234 | 161 |

| Armenian Catholic | 330 | 238 | 92 | 142 | 88 | 54 | 188 | 150 | 38 |

| Syrian Catholic | 171 | 69 | 102 | 146 | 59 | 87 | 25 | 10 | 15 |

| Assyrian Catholic (Chaldean) | 106 | 35 | 71 | 92 | 29 | 63 | 14 | 6 | 8 |

| ArmenanChurch (Gregorian) | 3,167 | 1,628 | 1,539 | 2,820 | 1,434 | 1,386 | 347 | 194 | 153 |

| Coptic Church | 219 | 128 | 91 | 161 | 90 | 71 | 58 | 38 | 20 |

| Abyssinian Church | 282 | 278 | 4 | 1 | 1 | … | 281 | 277 | 4 |

| Anglican Church | 4,799 | 3,320 | 1,479 | 1,810 | 911 | 899 | 2,989 | 2,409 | 580 |

| Presbyterian Church | 170 | 117 | 53 | 17 | 9 | 8 | 143 | 108 | 45 |

| Lutheran Church | 344 | 156 | 188 | 141 | 62 | 79 | 203 | 94 | 109 |

| Various denominations unclassified | 6,070 | 3,039 | 3,031 | 3,226 | 1,578 | 1,648 | 2,844 | 1,461 | 1,383 |

Subsidiary Table No. VII

Comparative Distribution of the Christian Churches 1922 and 1931 and

the Variation in Strength 1922-1931

| Churches | Population | Variation 1922-1931 | ||||

| Absolute | Proportionate | Absolute- Decrease(-) | Percent Decrease (-) | |||

| 1931 | 1922 | 1931 | 1922 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Total Persons | 91,938 | 73,024 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 18,374 | 25.2 |

| Orthodox Church of Jerusalem | 39,727 | 33,369 | 435 | 457 | 6,358 | 19.0 |

| Syrian Orthodox (Jacobite) | 1,042 | 813 | 11 | 11 | 229 | 28.2 |

| Roman Catholic | 35,578 | 28,412 | 389 | 390 | 7,165 | 25.2 |

| (a) Latin Rite | 18,895 | 14,245 | 207 | 195 | 4,650 | 32.6 |

| (b) Uniate Churches | 16,683 | 14,167 | 182 | 195 | 2,516 | 17.8 |

| Melkite (Greek Catholic) | 12,645 | 11,191 | 138 | 153 | 1,454 | 13.0 |

| Maronite | 3,431 | 2,382 | 37 | 33 | 1,049 | 44.0 |

| Armenian Catholic | 330 | 271 | 4 | 4 | 59 | 21.8 |

| Syrian Catholic Assyrian Catholic (Chaldeans) | 171 106 | {* 323 | 2 1 | {* 5 | {* – 46 | {* -14.2 |

| Armenian (Gregorian | 3,167 | 2,939 | 35 | 40 | 228 | 7.8 |

| Coptic | 219 | 297 | 2 | 4 | – 78 | -26.3 |

| Abyssinian | 282 | 85 | 3 | 1 | 197 | 231.8 |

| Anglican | 4,799 | 4,553 | 53 | 62 | 246 | 5.4 |

| Presbyterian | 170 | 361 | 2 | 5 | -191 | -52.9 |

| Lutheran | 344 | 437 | 4 | 6 | -93 | -21.3 |

| Various denominations unclassified | 6,070 | 1,758 | 66 | 24 | 4,312 | 245.3 |

Age – General

PALESTINE’S ACTUAL POPULATION AGED 23-73 YEARS

| Ages ending in | Males | Females |

| 3 | 13,205 | 10,796 |

| 4 | 10,717 | 9,866 |

| 5 | 64,675 | 69,576 |

| 6 | 11,7111 | 10,258 |

| 7 | 12,109 | 9,946 |

| 8 | 17,412 | 15,487 |

| 9 | 6,686 | 5,597 |

| 0 | 63,203 | 80,621 |

| 1 | 6,105 | 4,287 |

| 2 | 12,334 | 10,027 |

| Total | 218,157 | 226,461 |

The following table illustrates the grouping of the population aged 23 years and over by quinary groups beginning with unit digits 3 and 8 respectively:-

DISTRIBUTION OF THE POPULATION IN QUINARY AGE GROUPS BY SEX AND RELIGION

| RELIGION | MALES | |||||||||

| 23-28 | 28 | 33 | 38 | 43 | 48 | 53 | 58 | 63 | 68 | |

| Moslems (percent) | 30326 (100) | 27223 (90) | 20998 (69) | 19163 (63) | 13272 (44) | 13387 (44) | 6793 (22) | 8819 (29) | 4525 (15) | 4649 (15) |

| Christians | 5147 | 3724 | 2660 | 2245 | 1666 | 1776 | 1206 | 1201 | 785 | 667 |

| Jews | 11348 | 10380 | 6020 | 4709 | 2846 | 3093 | 2123 | 2276 | 1473 | 1305 |

| Palestine | 47294 | 41763 | 29997 | 26408 | 17995 | 18436 | 10257 | 12428 | 6869 | 6705 |

| RELIGION | FEMALES | |||||||||

| 23-28 | 28- | 33- | 38- | 43- | 48- | 53- | 58- | 63- | 68- | |

| Moslems (percent) | 31632 (100) | 30082 (95) | 20645 (65) | 21459 (68) | 12240 (39) | 14495 (46) | 5969 (19) | 10348 (33) | 4004 (13) | 5891 (19) |

| Christians | 4129 | 3675 | 2862 | 2781 | 2111 | 2172 | 1343 | 1569 | 929 | 898 |

| Jews | 11135 | 9335 | 5387 | 4537 | 3042 | 3313 | 2492 | 2686 | 1541 | 1260 |

| Palestine | 47379 | 43512 | 29205 | 29116 | 17586 | 20188 | 9715 | 14765 | 6557 | 8438 |

JUDAISM

(General)

During the years 1922-1931, the Jews increased from 83,794 persons to 174,610 persons and now form nearly 17 percent of the population of Palestine. Of the Jewish population enumerated, only 2 persons were returned as Karaites. Before the war, there were perhaps 80-100 Karaites in Palestine, but most of these departed to Cairo. Karaites are now mainly found in Russia. (p.85)

The Age Distribution of Jews (p. 120)

The Jewish age constitution as determined on the adjusted distribution has a well defined crest between the 15 years and 35 years – a range of life which may be taken to be coincident with that of the large part of the immigrant population. As in the case of the Moslems this crest may be a little wider and deeper than in the actual age distribution of the population, but in its configuration it satisfies normal expectation. The left hand side of the crest may reflect the effect of the war on the birth-rate of the Jewish population actually resident in Palestine during that period, but the Jewish population just after the war was estimated to be about 56,000, less than one third of the enumerated population in 1931, so that the war effect on this part of the curve can only be small. Neither will it be expected that the other major effect of the war, the mortality of males in the reproductive ages, should be manifested in the curve of the age distribution, because the present population is preponderantly immigrant in character so that a large number of males in the ages affected by the mortality due to the war is superimposed on the war losses which are thereby concealed.

The minor irregularities in the later ages of life may represent defects in the graduation or the effect of systematic distortions due to cyclic errors in the original returns centered round ages which are multiples of 5 years.

The interesting feature of the sex distributions is the remarkable parallelism generally manifest throughout life between the proportions of males and females at each age to males and females at all ages respectively. As at present composed the Jewish community is remarkably well balanced in the association of age and sex. The proportion of females in eh pre-nubile years is slightly less than the similar proportion of males; in the early reproductive years that proportion is slightly greater up to the age of 25 years and is met by the slightly greater proportion of males between the ages of 25 years and 42 years. This is an interesting distribution making for that form of sociological harmony which may be expected when biological needs are so naturally satisfied by conditions of age. Govern favorable economic circumstances, eh Jewish community, composed by age and sex as it is at present, is almost ideally constructed to fulfill social purposes. (p. 120)

The following table and Subsidiary Table No. III give the proportional age distributions in quinquennial age-periods for Palestine as a whole, the three districts, the three main religious confessions and the five towns of Jerusalem, Jaffa, Tel Aviv, Haifa Na Nablus. (p125)

DISTRIBUTION BY AGE OF POPULATION OF PALESTINE BY LOCALITY AND RELIGIOUS CONFESSION.

MALES

| AGE | DISTRICT | RELIGION | TOWN | ||||||||||

| Palestine | Southern District | Jerusalem District | Northern District | Moslems | Jews | Christians | Others | Jaffa | Tel Aviv | Jerusalem | Nablus | Haifa | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| All ages | 491,258 | 155,983 | 128,536 | 206,739 | 352,172 | 88,100 | 45,896 | 5,090 | 27,728 | 22,433 | 45,776 | 8,487 | 27,043 |

| 0-5 | 86,014 | 27,463 | 22,531 | 36,020 | 66,483 | 12,044 | 6,607 | 880 | 4,390 | 2,573 | 6,557 | 1,491 | 3,797 |

| 5-10 | 70,470 | 21,623 | 19,129 | 29,718 | 53,510 | 10,259 | 6,029 | 572 | 4,005 | 2,296 | 6,205 | 1,399 | 3,131 |

| 10-15 | 42,879 | 12,568 | 11,784 | 18,527 | 31,817 | 6,787 | 3,783 | 495 | 2,337 | 1,659 | 4,127 | 934 | 1,899 |

| 15-20 | 33,570 | 10,201 | 9,119 | 14,250 | 22,829 | 6,568 | 3,891 | 282 | 2,216 | 1,652 | 4,077 | 616 | 2,191 |

| 20-15 | 44,305 | 13,994 | 11,178 | 19,133 | 28,262 | 9,7750 | 5,915 | 378 | 2,843 | 2,149 | 5,176 | 738 | 3,394 |

| 25-30 | 46,566 | 15,036 | 10,949 | 20,581 | 30,534 | 11,241 | 4,299 | 492 | 2,468 | 2,690 | 4,431 | 621 | 3,421 |

| 30-35 | 35,757 | 11,911 | 8,506 | 15,340 | 23,440 | 8,741 | 3,177 | 399 | 2,091 | 2,486 | 3,488 | 532 | 2,661 |

| 35-40 | 30,480 | 9,850 | 7,421 | 13,209 | 22,194 | 5,364 | 2,611 | 311 | 1,762 | 1,566 | 2,514 | 430 | 1,840 |

| 40-45 | 22,973 | 7,450 | 6,008 | 9,515 | 16,759 | 3,985 | 1,960 | 259 | 1,580 | 1,227 | 2,122 | 418 | 1,335 |

| 45-50 | 18,909 | 6,983 | 4,837 | 7,989 | 14,181 | 2,812 | 1,706 | 210 | 986 | 900 | 1,537 | 340 | 937 |

| 50-55 | 16,777 | 5,686 | 4,416 | 6,676 | 12,156 | 2,796 | 1,662 | 163 | 1,043 | 878 | 1,468 | 286 | 832 |

| 55-60 | 10,127 | 3,428 | 2,822 | 3,876 | 6,756 | 2,097 | 1,137 | 137 | 483 | 672 | 1,024 | 196 | 453 |

| 60-65 | 11,837 | 3,930 | 3,433 | 4,474 | 8,427 | 2,164 | 1,119 | 127 | 626 | 699 | 1,116 | 222 | 462 |

| 65-70 | 6,411 | 2,043 | 1,963 | 2,505 | 4,383 | 1,,303 | 733 | 92 | 237 | 402 | 666 | 82 | 267 |

| 70-75 | 6,256 | 2,103 | 1,945 | 2,208 | 4,406 | 1,147 | 626 | 77 | 332 | 341 | 636 | 105 | 197 |

| 75 – | 7,541 | 2,420 | 2,462 | 2,659 | 5,961 | 834 | 631 | 115 | 311 | 191 | 604 | 76 | 200 |

| Not recorded | 286 | 194 | 33 | 59 | 67 | 208 | 10 | 1 | 8 | 151 | 18 | 1 | 25 |

DISTRIBUTION BY AGE OF POPULATION OF PALESTINE BY LOCALITY AND RELIGIOUS CONFESSION.

FEMALES

| AGE | DISTRICT | RELIGION | T O W N | ||||||||||

| Palestine | Southern District | Jerusalem District | Northern District | Moslems | Jews | Christians | Others | Jaffa | Tel Aviv | Jerusalem | Nablus | Haifa | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| All ages | 478,010 | 148,549 | 128,954 | 200,597 | 340,987 | 86,510 | 45,502 | 5,011 | 24,138 | 23,668 | 44,727 | 8,702 | 23,360 |

| 0-5 | 82,588 | 26,522 | 21,609 | 34,457 | 64,225 | 11,463 | 6083 | 871 | 4,122 | 2,547 | 6,199 | 1,477 | 3,404 |

| 5-10 | 62,810 | 19,248 | 16,917 | 26,645 | 46,771 | 9,836 | 4,457 | 636 | 3,470 | 2,323 | 5,670 | 1,290 | 2,991 |

| 10-15 | 35,597 | 10,303 | 10,016 | 15,278 | 25,242 | 6,465 | 3,365 | 425 | 1,833 | 1,601 | 3,767 | 751 | 1,763 |

| 15-20 | 29,642 | 8,855 | 8,530 | 12,257 | 18,555 | 6,921 | 3,878 | 288 | 1,816 | 1,980 | 3,994 | 643 | 1,853 |

| 20-25 | 43,412 | 13,886 | 10,809 | 18,717 | 28,556 | 10,921 | 4,404 | 431 | 2,558 | 2,783 | 4,483 | 725 | 2,732 |

| 25-30 | 46,668 | 15,201 | 11,475 | 19,992 | 31,449 | 10,806 | 3,942 | 471 | 2,202 | 3,154 | 4,129 | 738 | 2,722 |

| 30-35 | 37,718 | 12,073 | 9,765 | 15,680 | 16,488 | 7,459 | 3,182 | 389 | 1,969 | 2,262 | 3,285 | 701 | 19,92 |

| 35-40 | 29,876 | 9,027 | 8,249 | 12,600 | 21,653 | 4,967 | 2,929 | 327 | 1,284 | 1,498 | 2,543 | 473 | 1,400 |

| 40-45 | 26,168 | 7,917 | 7,272 | 10,979 | 19,403 | 3,984 | 2,465 | 316 | 1,340 | 1,212 | 2,362 | 475 | 1,160 |

| 45-50 | 18,140 | 5,505 | 5,037 | 7,598 | 12,790 | 3,004 | 2,159 | 187 | 755 | 935 | 1,642 | 329 | 803 |

| 50-55 | 18,875 | 5,850 | 5,212 | 7,813 | 13,659 | 3,027 | 1,996 | 193 | 932 | 890 | 1,779 | 383 | 818 |

| 55-60 | 9,620 | 3,017 | 2,879 | 3,724 | 5,920 | 2,288 | 1,308 | 104 | 337 | 748 | 1,120 | 141 | 439 |

| 60-65 | 14,196 | 4,295 | 4,078 | 5,823 | 10,130 | 2,459 | 1,458 | 149 | 652 | 665 | 1,428 | 223 | 499 |

| 65-70 | 6,56i0 | 1,863 | 2,047 | 2,650 | 4,040 | 1,523 | 914 | 83 | 180 | 456 | 818 | 97 | 245 |

| 70-75 | 7,880 | 12,320 | 2,483 | 3,077 | 5,655 | 1,289 | 852 | 84 | 342 | 322 | 819 | 130 | 239 |

| 75 – | 8297 | 2,472 | 2,555 | 3,170 | 6,195 | 900 | 991 | 111 | 343 | 214 | 676 | 126 | 295 |

| Not recorded | 163 | 95 | 21 | 47 | 56 | 98 | 9 | … | 3 | 78 | 13 | … | 5 |

Age distribution by sex, age and religious confession p. 128

The distributions of sex and age by religious confessions are of great interest. The second and third sections of the table show that for Moslems the preponderance of children in early ages in well marked and the diagrams reveal strikingly the unconscious social tendency among Moslems to obtain smaller degree of disparity between the sexes, the proportion of each sex and 9-5 years in ten thousand of each sex being very nearly equal…. the birth-rate was falling in the year prior to the war:. Upon this natural movement have been superimposed those social tendencies derived from the benefits of a service of public health reducing the incidence of fatal epidemics and the number of infant deaths. These two sets of tendencies in the same direction have materially altered the demographic character of the local population; and it will be seen later that the native-bon population of Palestine can now be defined as progressive whereas before the war it as at best stationary or, more probably, regressive. The point is of considerable importance because a population which becomes or is made suddenly progressive has considerable difficulty in making the necessary economic adjustments. What may be called the tradition of population is no more than the attempt to establish stable equilibrium between requirements and the means of satisfaction, and a sudden disturbance of that tradition due to any cause of social or economic origin must be necessarily be followed by local maladjustments with consequential social discomforts. Such consequences, of themselves, lead to a better adaptation of resources and means; and, up to a certain limit, known as the optimum; an increasing population creates new sources of productive activity to meet the needs of the growing people. The history of population elsewhere shows that he optimum population for Palestine cannot be assigned to a remote future and, notwithstanding the youthfulness of the Moslem and the rural population revealed by the census, it may be anticipated that the rate of increase of the natural population within Palestine will not be maintained for long at its present level.

The distributions of the Christians are affected by the presence of immigrant populations of His Majesty’s Forces, the members of the Civil Service and of the monasteries and convents. The distortions in the age distributions due to these influences are strongly marked in the second and third sections of the table and in the diagram. There is a most emphatic deficiency of children up to the age of 10 years; there is a most marked effect of immigration of males in the ages 15 years to 35 years; thee is a decided “agedness” of the community in comparison with others and with the chosen standard population; and there is a remarkable excess of the proportion of females of the age of 35 years and upward among females over the proportion of males at the same ages in the male population. These features are directly traceable to the influences mentioned above. The group as composed is badly balanced both in age and in sex composition; but, since the distortions are introduced mainly through the foreign-born part of the community, the phenomenon is of no serious social consequence. The discussion in Chapter IV (Religion) has revealed the relative magnitudes of the foreign and native born Christians and that the number of European and American Christians is about 10,000; and knowledge of the facts that British soldiers and British police are in the early reproductive years of life, but on the whole, unmarried, and that conventual populations are, by the nature of their vocation, not reproductive, is sufficient to explain the characteristics of the age curves for Christians. In fact the distortions may be great enough to disguise the real features of the native-born Christian community, certainly on its male side, and to a smaller extent on its female side.

The main features of the Jewish distributions are the comparatively great deficiency in children of early ages and the emphatic excesses in the immigration period from the ages of 15 years to 35 years. Between the ages of 55 years and 75 years the proportions of each sex are on the whole higher than those in each sex of the total population and those in both sexes in the standard population. As for the Christians with their disturbing group populations, the force of mortality does not appear to have the same destructive effects at these later ages as are manifested among the Moslems. There may be in both communities a special immigration of aged people who desire to be in the Holy Land at the time of death. On the other hand it is well established that primitive people are comparatively short-lived and there appears to be a direct association between longevity and modern civilized life. In so far as longevity can be regarded as a measure of civilization, the Christian community with its foreign elements takes the first place at present among the communities ranked according to such a scale. This question is considered more fully in a later section of this chapter, but it may be observed here that the ranking may change as the immigrant Jewish population passes in the period of old age. There is also manifested in the Jewish community an ideal proportion between the sexes at most ages in life.

Some time has been expended on the discussion of the statistics arranged according to religious confession, because, unless the characteristic features of the three principal communities are fully understood, it is not possible to appreciate the significances of the age and sex distributions in the districts and the towns. In summary the principal features of the distribution by religious confessions are set out below:

(i) Moslem -Population growing younger: not affected to a marked extent by migration

(ii) Jews – Population affected greatly by immigration in the ages 15-35 years: longevity greater than that of the Moslems.

(iii) Christians – Population affected by special types of immigration reducing the reproductive capacity of the community as a whole; comparatively great longevity.

These main characters must be kept in mind in considering the age and sex distributions of districts and towns. On the whole the characters of the districts are governed by the characters of the rural population which is dominantly Moslem, but the effects of the Jewish and Christian populations in the towns of Jerusalem, Haifa and Tel Aviv may be expected to be manifest: while the Jewish population of the plains of Esdraelon and Jezreel may be expected to influence the distributions for the Northern district. Of the towns, Nablus should give a predominantly Moslem picture altered by the special features of its parochial and economic existence, while Tel Aviv may be expected to give typical Jewish distributions. p. 131

Death Rates p. 143

The declared general death-rates for the period 1923-1931 are set out in Subsidiary Table No. V. wherein corrected rates for sex and religious communities for the year 1931 will also be found.

The general crude death rates (corrected) for 1931 are 26.2 for male Moslems, 25.7 for female Moslems; 9.6 and 9.2 for Jewish males and females; and 14.6 and 14.2 for Christian males and females. These rates approximately give the Jewish and Christian communities the same rate of natural increase (about 22 per thousand persons) at the present time, the Moslem rate of natural increase being between 27 and 28 per thousand. Since immigration is of no account among Moslems there is, therefore, a tendency not to maintain the annual rate of increase manifested over the period 1922-1931. The standardized death-rates are given in the following table: –

STANDARDIZED DEATH-RATE PER THOUSAND OF POPULATON 1931

| Religion | Persons | Males | Females |

| All religions | 21.51 | 21.77 | 21.29 |

| Moslems | 25.69 | 25.92 | 25.51 |

| Jews | 9.29 | 9.63 | 9.02 |

| Christians | 13.82 | 14.30 | 13.44 |

They do not differ materially from the crude rated because the actual age composition of the standard population is almost identical with that of actual population. The age-groups adopted in the declared general rates are not well adapted for the determination of the standard death-rates: the groups 10-20 years, 20-50 years and 50 years and over are too large to enable significance to be given to mortality occurring as a result of early childbirth or the onset of senility. In order to obtain some idea of the mortality in Palestine, standardized rates based on the standard population of England and Wales 1901 have been calculated and are given in the following table: –

STANDARD DEATH-RATES ON ENGLISH STANDARD MILLION 1901

| Country | Year | Religion | Standard Death-rate | ||

| Persons | Males | Females | |||

| England and Wales | 1913 | … … … | 5.6 | ||

| 1924-1926 | … | … | 11.6 | 9.5 | |

| All religions | 17.5 | … | … | ||

| Palestine | 1931 | Moslems | 19.5 | … | … |

| Jews | 9.5 | … | … | ||

| Christians | 13.2 | … | … | ||

p. 158

Corrected Rates for 1931 per 1,000

| Religion | Birth Rate | Death Rate | ||||

| Persons | Males | Females | Persons | Males | Females | |

| All Religions | 47.7 | 48.9 | 46.5 | 21.8 | 22.1 | 21.5 |

| Moslems | 53.2 | 54.4 | 51.9 | 26.0 | 26.2 | 25.7 |

| Jews | 31.8 | 32.6 | 31.0 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 9.2 |

| Christians | 36.3 | 37.1 | 35.5 | 14.4 | 14.6 | 14.2 |

P. 159

SUBSIDIARY TABLE No. VI

Infantile mortality 1923 – 1931. – Number of deaths per 1,000 births*

| Year | Moslems | Jews | Christians | |||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| 1923 | 172.8 | 163.8 | 130.2 | 114.9 | 119.3 | 135.0 |

| 1924 | 179.3 | 172.5 | 102.9 | 103.0 | 148.3 | 145.6 |

| 1925 | 176.3 | 170.3 | 131.5 | 134.4 | 154.8 | 158.6 |

| 1926 | 156.3 | 146.8 | 114.9 | 98.6 | 148.9 | 154.1 |

| 1927 | 200.3 | 184.1 | 127.8 | 105.0 | 189.6 | 180.4 |

| 1928 | 184.5 | 171.8 | 99.4 | 87.3 | 135.3 | 165.3 |

| 1929 | 190.3 | 181.7 | 92.4 | 85.4 | 157.9 | 156.3 |

| 1930 | 158.0 | 146.6 | 75.0 | 61.7 | 114.7 | 144.4 |

| 1931 | 168.7 | 166.4 | 72.8 | 90.7 | 125.7 | 137.4 |

- The absolute statistics are given in Subsidiary Tables Nos. IV & V at the end of Chapter VI.

It will be seen that there is no correspondence between these mortalities by sex and the declared infant mortalities by persons. The reason is that the absolute statistics, revised for census purposes by the Department of Public Health and found at the end of Chapter VI (Sex), do not correspond with the absolute statistics given in the series of annual reports of the Department of Public Health.

Literacy p. 205

Careful consideration was given to the whole matter before it was decided to proceed with an inquiry into literacy in Palestine through the agency of the census. It was finally decided to impose no tests but to allow the people to make their own subjective declarations as to their possession or lack of literacy, and then to supplement those declarations by an inquiry into the length of attendance at any educational institution of any type whatever. The information obtained by this means is, of course, crude; but when it is associated with the ages of the persons, it is instructive as regards both the effective educational differences between pre-war Turkish and the post-war British administrations, and also general educational policy at the present time. Education is undoubtedly regarded by all the inhabitants, even the nomads, as a desirable thing, not perhaps in essence but as a means to material advancement; and it is possible that subjective declarations reflect not only that this desirable thing is desired, but that it has been gained, so that a greater number of persons have been returned as literate than could be regarded as literate on any standard; on the other hand, a number of persons in adult years declared that they were illiterate notwithstanding the fact that they had attended some educational institution for a period in their young ages. Among literate people, a confession of a decline in literacy with advancing years is unusual: but, since the majority of the population of Palestine are illiterate, the experience of a literate population may be irrelevant. The alternative interpretations are, therefore, either that such illiterate persons have told the complete truth about themselves, or that they have sought to attach to themselves those superior qualities, other than literacy, which the mere attendance at school may be supposed to confer. Since, however, the truth in regard to either matter is well known in a village community, there was no more reason for falsehood in regard to school attendance than there was for truth in regard to literacy. It would appear, therefore, that the returns are likely, on the whole, to be truthful and that the information, so far as it goes, valid. p. 205

Taking the country as a whole, and considering the population aged 5 years and over, there are 300 literate persons per thousand, being 404 literate males and 211 literate females per thousand of the respective sex. These proportions rise to 326,428, and 221 respectively for the population aged seven years and over. The statistics by religious confession show the widest diversity between the respective communities. The statistics are repeated below: –

| Age in Years | Literate per thousand | ||||||||||||||

| All religions | Moslems | Jews | Christians | Others | |||||||||||

| Persons | Males | Females | Persons | Males | Females | Persons | Males | Females | Persons | Males | Females | Persons | Males | Females | |

| 5 & over | 309 | 404 | 211 | 135 | 234 | 32 | 834 | 903 | 765 | 555 | 683 | 427 | 199 | 343 | 101 |

| 7 & over | 326 | 428 | 221 | 144 | 251 | 33 | 861 | 934 | 787 | 577 | 715 | 441 | 233 | 362 | 104 |

The minor religious confessions are here included because over 90 percent of the persons forming this class are Druzes, so that the proportions stated for this reason of the fact that the class includes a small number of educated persons adhering to confessions either not classified or having no confession.

Only one fourth of the male and less than one thirtieth of the female Moslem population have been returned as literate: over 90 percent of the Jewish males and nearly 80 percent of the Jewish females have been returned as literate: the proportions for the Christians are about 90 percent for the males and rather more than two fifths for the females: while for the Druzes the proportions are about one third for the males and one tenth for the females. The answer to the census question as to literacy is, according to the declarations of the people themselves, that the Jews are predominantly the literate community, the Christians taking second place, the Druzes being third but considerably behind the Christians, while the Moslems are the most illiterate, being notably worse than the Druzes. p. 206

The table is interesting as showing that the mixture of cultural standards in Palestine has the effect of placing the whole population, as regards literacy in a position midway between the western and the oriental countries. While the Jews of Palestine easily have priority in the table in regard to male literacy, the Christians begin to approach the average standards of the European countries shown, and the Moslems take place with those of Egypt and Asiatic countries in respect of both sexes. The figures shown for Moslems in the Indian province of Bengal are interesting as showing that the prevalence of illiteracy among Moslems in Mediterranean countries should not, perhaps, be attributed solely to the deadening influences of Constantinople on Arab Moslem life. It would seem that the traditional early teaching of prayers and of verses from the Quran to Moslem boys has taken the place of secular education in regard to reading and writing usual among other communities in these early years of life. The postponement of secular education, in a community unable easily to find an economic existence, must have inevitably led to complete lack of opportunity to take advantage of such facilities for secular education as were provided, and hence to the high proportion of illiteracy in the community. p. 208

From this point of view the comparison between the illiteracy of Palestine and that of Egypt by the three communities is of great interest. The table is given below: –

NUMBER OF ILLITERATE PERSONS PER 1,000 OF POPULATION AGED 5 YEARS AND OVER BY SEX AND RELIGION

| Country | Year Of Census | Moslems | Christians | Jews | ||||||

| Both Sexes | Males | Females | Both Sexes | Males | Females | Both Sexes | Males | Females | ||

| Egypt | 1927 | 886 | 797 | 975 | 640 | 530 | 751 | 273 | 183 | 360 |

| Palestine | 1931 | 865 | 766 | 968 | 445 | 317 | 573 | 166 | 97 | 235 |

It will be seen that, notwithstanding the educational advantages given in Egypt for many years, the Moslems of Palestine show a slightly better condition of literacy than the Moslems of Egypt.

Considerable interest attaches to the low proportion of illiteracy among the Jews. The following table gives comparisons between Palestine and other countries in this respect: –

NUMBER OF ILLITERATE JEWS PER 1,000 JEWS IN DIFFERENT COUNTIRES AND TOWNS

| COUNTRY | Year of Census | Aged 5 years and upward Both sexes | ||

| Russia | 1926 | 290 | ||

| Ukraina | 1926 | 300 | ||

| White Russia | 1926 | 312 | ||

| Lithuania | 1923 | 323* | ||

| Hungary | 1920 | 44† | ||

| Bulgaria | 1920 | 310§ | ||

| Egypt | 1927 | 273‡ | ||

| Palestine | 1931 | 166 | ||

| TOWN | Aged 5 years and upward | |||

| Both sexes | Males | Females | ||

| Leningrad | 1926 | 119 | … | … |

| Moscow | 1926 | 137 | … | … |

| Ukrainia (Urban population) | 1926 | 284 | … | … |

| White Russia (Urban population | 1926 | 309 | … | … |

| Kaunas | 1923 | … | 164 | 270 |

| Jerusalem ‡ | 1931 | 224 | 105 | 333 |

| Tel Aviv ‡ | 1931 | 71 | 30 | 110 |

| Haifa ‡ | 1931 | 99 | 49 | 130 |

| Jaffa ‡ | 1931 | 331 | 213 | 448 |

*Age 10 years and over. †Age, 6 years and over. § Age, All ages ‡ Age 7 years and over. p. 209

The preceding general discussion has shown the need for more detailed examination of literacy of the three main communities. The Moslem population is roughly 70 percent of the settled population, but of the number of literate persons of all religions only 30 percent are Moslems. If the nomadic populations, which are all Moslem, be included the disparity is, of course, even greater. A more striking illustration is afforded by a comparison between the least and most literate of the communities: the Moslem population is four times the Jewish population while the number of illiterates among Moslems is thirteen times the number of illiterates among Jews. A glance at Subsidiary Table I shows that in every hundred Moslems of both sexes’ ages seven years and over only 14 are literate, the proportions for the sexes at these ages being 25 for males and only 3 for females. Subsidiary Tables III and IV show the very striking differences between the proportions of literate Moslems in the urban and rural populations. It is natural to expect that persons living in towns should be more literate than those living in the rural areas, if only because it is easier to provide educational facilities in more densely populated areas. It will be seen that taking both sexes together the proportion of literacy in the towns is 260 per thousand and 217 per thousand according to the class of towns, that is, on the whole, more than double the proportion for the rural population, 109 per thousand; while the proportion of literate females is most emphatically higher in the urban population being 6 per thousand in the rural population and 140 and 95 per thousand in the two classes of towns. There are, however, large variations in the proportions as between town and town, Jerusalem returning the highest with 366 per thousand and Jaffa the lowest with 210 per thousand. Even when preeminently rural towns such as Khan Yunis and Majdal in the Southern district are examined, it is found that the proportion of literacy in their populations is markedly higher than the average proportion in the village population. In general it may be said that the statistics reflect an unevenness inevitable where education is not compulsory: and that there is a very wide disparity between the males and females of the Moslem community in literacy, partly due to the tradition that eastern women need not be educated, and partly due to the lack of facilities for female education. The literacy among Moslem females in Jerusalem is, of course, weighted to some extent by the presence at the time of the census of girls in educational institutions who live outside Jerusalem. This in itself, is an indication that the traditions as regards female education are not likely to survive if the means for education are available.

The correlation between Moslem literacy and age reveals that the largest proportion of literates is in the age group 7 – 14 years. The British Occupation had lasted thirteen years by the time of the census so that, for all practical purposes, the surviving population aged 14 – 21 years was born either in the years of the war or in the four years preceding it. The fact that the proportion of literates is higher in the age group 7 – 14 years than in the group 14 – 21 years is an indication that progress has been made in granting educational facilities since the war, since the decline in literacy with advancing years is not likely to be emphatic between the ages of 14 and 21 years. This improvement is more marked in the rural population for males and in the urban population for females, although, in the case of girls, allowance must be made for a concentration in the towns due to residential institutions in which education is given to girls from various parts of the country. The proportion of literacy is a minimum in the age group 21 years and over indicating clearly a lack of educational facilities for the population born before the war, and also a probable decline of literacy with advancing years.

The Christian population is in a greatly better condition of literacy than the Moslem community. More than 70 percent of the males and almost 45 percent of the females aged 7 years and over are literate. The difference between the male and female proportions of literacy is reduced to a minimum in the main age group 7 – 14 years; while the proportions are almost equal in the small age group 5 – 7 years. The indication is that the young generation of Christian females is taking progressive advantage of the educational facilities available in the country.

It has been already noted in the preceding section of this chapter that, regarded by district distribution, Christian literacy is highest in the Southern district. In Jerusalem the proportion literate of the age of 7 years upward is as high as 75 percent. Jerusalem however provides an especially literate population by reason of the presence of a significant number of Europeans living in the city.

The difference between the urban and rural populations as regards literacy is well marked but in a smaller degree than is the case with the Moslem population. The proportion of literacy for both sexes together is about 50 percent higher in the urban than in the rural population.

The examination of literacy by age elicits one interesting phenomenon, namely, that the proportion of literacy is highest in the age group 14 – 21 years. The population in this group, born either just before or during the war, would begin its education in the years immediately following the war. The fact that the proportion of literacy is higher in this group than in the age group 7 – 14 years may imply regressive features in the educational policy influencing the Christians, and may suggest that educational facilities in the years just succeeding the war were more numerous than during the last five or six years. Against that, however, as will be seen from the third section of this chapter, it can be argued that some children in the earlier years of the age group 7 – 14 years are not attending school, and begin to make use of educational facilities in the later ages of this group and the earlier ages of the age group 14 – 21 years. The inference can be drawn therefore that late attendance at school is responsible for the higher proportion of literacy in the later age group. Moreover, the Christian community is disturbed both by immigration and emigration. Young illiterates may realize that the opportunities for their absorption in the economic life of the country are not many, and may therefore emigrate to countries where their manual labor will assure their support. The effect of such a movement on the proportion of literate in these ages would be an increase in the ration. Equally there may be an immigration of young literates from Syria which would have the effect of a significant increase in the proportion of literacy at these ages; and, finally, the presence of young soldiers in His Majesty’s Forces, all of whom are literate, will also raise the proportion of literacy in the ages round about twenty years.

It has already been recorded that the proportion of literacy in Palestine is highest among the Jews, of the males of whom 93 percent are literate, and of the females 79 percent. The distribution of literacy by districts shows remarkable variations, the maximum being manifested in the Southern district which is governed to a large extent by the population of Tel Aviv where 97 percent of the males and 89 percent of the females have been returned as literate. The differences between the proportions of male and female literates are considerably smaller than those exhibited by the Moslem and Christian communities particularly at school ages. Nevertheless of the females aged 7 years and upward more than one fifth are illiterate, while in the age group 7 – 14 years in the different districts 17 – 18 percent of the females are illiterate.

Contrary to usual experience, the literacy in the Jewish rural population is higher than that in the urban population. I all age groups, and especially among females, the literacy in the villages is higher than in the towns: while in the age group 14 – 21 years the proportion of literates among Jewish males reaches the extraordinary figure of 99 percent. The following reasons account for this phenomenon: first, the oriental Jewish communities, among whom the highest proportions of illiteracy are found, are concentrated in the towns: secondly, life in the villages has a strong attraction for educated immigrant Jews: thirdly, admission fees in the Jewish village schools are low, the villages themselves contributing by voluntary levy to the maintenance of these schools; and, lastly, there is small demand for domestic service in the villages so that young girls are enabled to attend schools, whereas, in the towns, some of the domestic work of households is done by girls of school age.

The statistics of literacy by age reveal the phenomenon of a higher proportion in the age group 14 – 21 years than in the earlier age group – a phenomenon already noted in the case of the Christian population. Here again the reasons may be found in a proportion of late attendance at school in the age group 7 – 14 years, and in the immigration of literates from Europe in the age group 14 – 21 years.

This brief summary leads to the following conclusions as to the nature of the educational problems of the future: –

(i) The problem of Moslem education is the provision of greatly increased facilities for primary education and an extension of the means for educating the younger females.

(ii) The problem for the Christian community is the provision of means for gradually extending the present facilities.

(iii) The problem for the Jewish community is the maintenance of the present high standards of primary education, and the creation of extended facilities for educating the members, particularly the female members, of the communities of eastern Jews.

ATTENDANCE AT SCHOOL

It has been explained in the first section of this chapter that it was considered desirable to inquire more closely into the question of the literacy of the population by eliciting information as to whether the persons enumerated had ever attended some kind of educational institution, without specifying its character, and if so, for how many years. The absolute statistics are given in Table IX-A in Volume II of this Report, and the following Subsidiary Tables are given at the end of this chapter: –

It will be seen from Subsidiary Table V that, in the age period 0 -7 years, while 1 percent of the Moslem males and 0.5 percent of the Moslem females have attended school, the proportions for the Jews are nearly 14 percent and 13 percent respectively for males and females, the proportions for Christians being about 7 percent. In the case of the Christians the proportion is slightly in favor of the females as against the males, the differences in the other communities being slightly in favor of the males. There is therefore striking evidence of the fact that Jews tend to begin the institutional education of their children before the age of 7 years. If the figures published in the Annual Report of the Department of Education 1931 be taken, it will be found that the percentage ration of Jewish children aged 4 – 7 years attending the schools of the Jewish Agency to the total Jewish child-population aged 4 – 7 years is 41 percent for boys and 52 percent for girls. These ratios are smaller than the true ratios which will be based on the population attending all Jewish schools and not only those of the Jewish Agency. The absolute figures are not available but it is probable that 60 percent of the Jewish children aged 4 – 7 years are attending some kind of institution for education. No statistics are given in the Annual Report of the Department of Education regarding the ages of Moslem and Christian pupils in schools not directly administered by the Government: but the general proportions of attendance at school in the age group 0 – 7 years in the three communities indicate that the proportions of Moslems and Christian children aged 4-7 years attending schools is considerably smaller than the proportion of Jewish children: and it is not an unsafe inference that the proportions in these two communities would be raised if educational facilities of the kindergarten type were available.

Taking the population aged 7 years and over, only 23 percent of the Moslem males and 3 – 4 percent of the Moslem females have attended school. The similar proportions for Jews and Christians are 88 percent and 75 percent for Jews, and 66 percent and 42 percent for Christians. In both the Jewish and the Christian communities the highest proportion of education at school is found in the age group 14 -21 years, while in the Moslem community the maximum proportion is in the age group 7 -14 years. The principal inference to be made is that it is only in recent years that progress has been made in providing educational facilities for Moslems: there is a secondary inference that, while the proportion of children in early years attending school is greatly higher in the Jewish and the Christian communities than in the Moslem community, some of the children begin their education later in life and do not complete it until they are in the age group 14 – 21 years. In fact Jewish and Christian parents do their utmost to send their children to school at some time: if they cannot afford it when the children are young, they strive to make it possible when they are older. This may explain, so some extent, the rather wide range of age in classes, which is experienced in many schools in the country, children of very different ages being roughly of the same standard of education. The age group 21 years and over has a special significance in that the survivors at these ages were born in the years prior to the war. These persons, particularly those of the Moslem community, are therefore associated with educational facilities provided before or during the war. Only 20 percent of the Moslem males and less than 2 percent of the Moslem females at these ages have attended an educational institution. It will also be noted that of Jewish females aged 21 years and over more than 30 percent have never attended a school.

In general, the degree of literacy of persons varies directly with the period of attendance at an educational institution. Disturbance is introduced into the general rule by persons who are below the norm and who, therefore, cannot complete normal studies in average time. A further disturbance is introduced into the general rule as applied to Palestine, and particularly the Jewish community, by the fact that a proportion of the younger immigrants come from European countries, particularly Russia, having completed their primary education in Jewish schools where there was no admission fee, but having been debarred from secondary education, either because they could not afford the fees, or because schools in which higher education is given are State institutions with stringent restrictions as to qualifications, not necessarily educational, for admission. In Palestine such persons have sought to begin and continue their secondary education at ages somewhat above the normal associated with their standard of education.

The following table shows the distribution per thousand who have attended school for stated periods of years: –

NUMBER PER 1,000 WHO HAVE ATTENDED SCHOOL FOR CERTAIN PERIODS OF YEARS.

| Years at School | Moslems | Jews | Christians | |||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| All ages | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| 0 – 4 | 655 | 651 | 181 | 262 | 387 | 454 |

| 5 – 8 | 275 | 297 | 422 | 466 | 349 | 373 |

| 9 – 12 | 56 | 49 | 277 | 216 | 215 | 145 |

| 13 and over | 14 | 3 | 120 | 56 | 49 | 28 |

There are several interesting features in this table. Two thirds of the Moslems who have attended school have so attended for less than five years only; and 1.4 percent of the males and 0.3 percent of the females have attended for 13 years or more. Of the Christian population, two thirds of those who have attended school have attended for at least five years. This proportion is a little higher than the true proportion by reason of the fact that European Christian males living the conventual life have been returned as engaged in study for most of their lives. In the Jewish community about 80 percent of those who have attended school have done so for at least five years.

The question of literacy in the communities, having been viewed from three angles, leads definitely to the conclusions that literacy depends on educational facilities and that the literacy in Palestine in the Moslem community and to a smaller extent in the Christian community is predominantly caused by lack of those facilities.

It is of interest to note that while, in general, females remain at educational institutions for shorter periods than males, yet, in each community, the proportion of females remaining for a period of 5-8 years at schools is higher than the proportion of males. It would appear that, on the whole, males remain at school either for short or for long periods, while females remain for an intermediate period. This phenomenon is, not doubt, a reflection of economic and sex conditions. A boy’s life is conditioned to some extent by the material circumstances of his family: he may be obliged to assist the earner at an early age. If, on the other hand, higher education can be afforded the boy is given the maximum benefit of attendance at school, so that he may acquire qualifications enabling him to enter professional occupations regarded as suitable to the status of his family. Girls who attend schools for a period of 5-8 years will, on the whole, be members of families whose material circumstances are well removed from the poverty line, and such girls will not, in general, be required to acquire qualifications of economic value.