The Jewish State, Theodor Herzl

(1896)

Herzl, Theodor. “The Jewish Question.” The Jewish State. Trans. Sylvie D’Avigdor. 1896. N.p.: American Zionist Emergency Council, 1946. N. pag. Print.

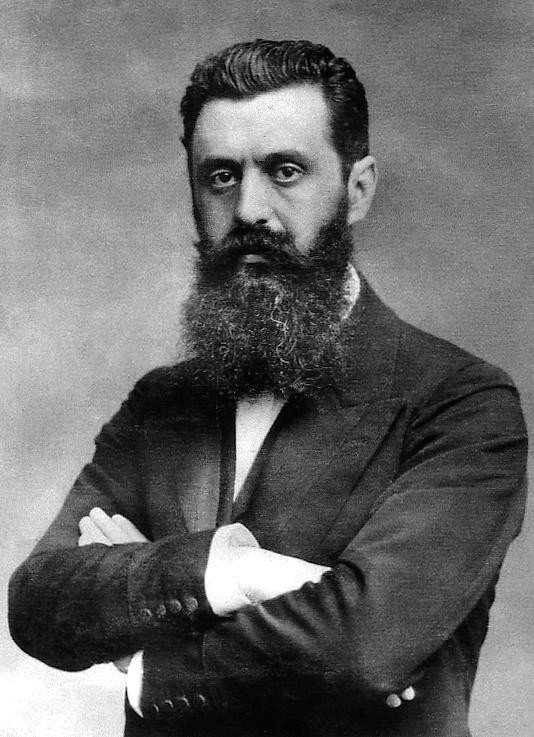

The origins of the Zionist movement are often considered synonymous with the life and times of Theodor Herzl (1860-1904). Though Herzl died at a relatively young age, his ideas persevered; the Zionist movement did not collapse because its central figure died only seven years after the first Zionist Congress met. The dream to recreate a Jewish presence in the Holy land, Eretz Yisrael or Palestine, had extraordinary depth and variety. Two decades before Herzl died, Jews were immigrating in small numbers to Palestine, building settlements and a new life, distant from the vicious anti-Semitic outbursts that drove many to leave Eastern and Western Europe. Herzl was a catalyst for reconnecting Jews to their ancient homeland, forging a cohesive organization from the teeming debates amongst many European Jews about the desirability of a Jewish territory to provide for Jewish security.

Born in 1860 in Hungary and schooled in Vienna, Herzl had neither a remarkably profound nor distant relationship to Judaism. In his youth, he read a great deal, enjoyed secular literature, wrote short stories, poetry, fables, comedy, and was completely absorbed in German literary culture. He earned his law degree and was admitted to the bar in Vienna in 1884. For the next decade, he wrote articles, plays, novels, traveled major cities of Europe, and in October 1891, became the Paris correspondent of the Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Presse, which was considered the most distinguished newspaper in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Herzl’s appointment reflected his competence as a writer and journalist. In Herzl’s early life, he did not encounter much anti-Semitism, but by 1892, his paper carried an increasing number of articles about Jews, the Jewish question, and anti- Semitism. These included articles about the persecution of Jews in Russia, the status of Jewish colonies evolving in Argentina with the support of the Jewish philanthropist Baron de Hirsch, and debates on the Jewish right to civic equality that were taking place in Berlin and Vienna. In August 1892, he wrote a long article on anti-Semitism, but offered no particular political solution. According to the 1906 edition of the Jewish Encyclopedia, he was “least aware” of his Zionist intellectual forerunners Moses Hess, Leon Pinsker, Reuven Alkalai, and Nahum Syrkin; hence he was ‘wired’ to emerge as a prominent Zionist leader, let alone become the “father of modern ZiHoneirszml .c”overed the Dreyfus trial as a correspondent for his paper. Alfred Dreyfus, an assimilating French Jewish military captain, was arrested in October 1894. By the end of that year, he was tried, convicted, court-martialed, and incarcerated for allegedly passing information about French artillery capabilities to a German military attaché in Paris. Based on fragmentary evidence and an absence of due process, his case was reopened in 1899. Despite these legal points, Dreyfus was reconvicted and sentenced to another ten years. Finally, in 1906, he was exonerated and released from prison. There is little doubt that the trial gave anti-Semitism stunning notice in what was believed to be an emancipating Europe; “in France it took on the dimensions of a civil war and rent European opinion asunder.” 1

Zionist historiography and popular Zionist history gives overwhelming weight to the catalytic role that the Dreyfus trail had in motivating Herzl to write his treatise, “The Jewish State.” Alex Bein, in his classic biography of Herzl, claimed that Herzl possessed not the slightest evidence on which to base Dreyfus’ innocence. Herzl wrote, “A Jew who, as an officer on the [French] general staff, has before him an honorable career, cannot commit such a crime…the Jews, who have so long been condemned to a state of civic dishonor, have as a result, developed an almost pathological hunger for honor….” Bein concluded that Herzl found it “a psychological impossibility” for Dreyfus to have committed such a crime. That was 1894; five years later, Herzl wrote at the time of the case’s reopening that it “embodies more than a judicial error; it embodies the desire of the vast majority of the French to condemn a Jew, and to condemn all Jews in this one Jew.” 2

In “The Jewish State”, Herzl called for Jews to organize themselves so that they could gain a territory of their own, to create institutions and forums, to oversee Jewish immigration and settlement and eventually create a state. Under his short watch, as president, he established the World Zionist Organization, conducted regular meetings of Zionist Congresses, and helped found the Jewish National Fund and Jewish Colonial Trust. The first Zionist Congress of some 200 delegates from all over Europe met in Basel, Switzerland in August 1897. Among the most salient entries in his diary are the passages from September 1897; “Were I to sum up the Basel Congress in one word–which I shall guard against pronouncing publicly–it would be this: at Basel I have founded the Jewish state. The foundation of a state lies in the will of the people for a state. . . Territory is only the material basis: the state, even when it possesses territory, is always something abstract. . . . At Basel, then, I created this abstraction which, as such, is invisible to the vast majority of people–and with minimal means. I gradually worked the people into the mood for a state and made them feel that they were its National Assembly.” 3

After the publication of “The Jewish State” and the conduct of the First Congress, Herzl became the maestro for political Zionism, its cheerleader, organizational guru, and diplomatic envoy to capitals and leaders of Europe and the Ottoman Empire. He crystallized existing feelings from individuals who wanted to see the establishment of a Jewish state and bestowed upon Zionism working structural frameworks. Herzl drove the movement by gaining notice amongst Jews and non-Jews alike of the Jewish desire for a state. He gave Zionism an address and imbued it with charismatic, if not authoritarian, leadership. Herzl succeeded because there were hundreds, even thousands of Jews enamored with the notion of Jewish self-determination. He showed that international diplomacy mattered even if securing support initially was rejected or not enthusiastically provided. In the two years before his death, Herzl met and introduced the idea of a Jewish home to numerous British officials (Arthur James

Balfour, Lord Milner, Sir Edward Grey, and Lloyd George), all of whom would be instrumental in supporting the 1917 Balfour Declaration’s call for British support in Palestine of “a national home for the Jewish people.”

Herzl did not leave the Zionist movement either uniform or homogenous in definition or outlook. In his short lifetime, he did not tackle with any candor the issue of a Jew’s loyalty to the state in which they lived as compared to support of Zionism; Herzl said very little about Arabs living in Palestine as an issue or problem that Zionists might confront in the future. And Herzl and his colleagues split on how best to achieve their objective: some thought it more advisable to seek permission from a great power to support a Jewish homeland, while others thought it best to first undertake practical work of physically returning to Palestine. Herzl sought but failed to obtain a ‘charter,’ or sanction, from Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II to support Zionism. Meanwhile, Jews emigrated from Eastern Europe in droves, running from the anti-Semitic outbursts in Russia, particularly the pogroms in the early 1900s. Most of the Jews who emigrated from European areas moved to the west, primarily to the United States, South America, and South Africa.

At the turn of the century, only a handful of Jews immigrated to Palestine, some settling permanently, others testing the settings only to realize the move there was to too harsh and thus, for many, their stay was short-lived. Meanwhile, Russian pogroms against Jewish life and property reignited in places like Kishinev, Gomel, Bialystok, and other places, numbering 660 small and large attacks between November 1 and November 7. Herzl renewed a Zionist drive to land permission from Russia or England to sanction a place for a Jewish homeland, but failed. Prior to Herzl’s sudden death at 43 in July 1904, disparate Zionist leaders eventually crystallized a view that both practical (settlement) and political (seeking a charter or permission) should move in parallel, one reinforcing the other. A young Zionist leader who would emerge as an important cog in Jewish nation building over the next forty years, Menachem Ussishkin said that the movement had to attain the charter (permission from a great power or number of powers) to build a national home from the top down, and simultaneously through practical work from the bottom up in Eretz Yisrael. As it evolved as a movement, a variety of thinkers stamped their preferences on Zionist development. Nachman Syrkin and Ber Borachov sought to synthesize Zionism with Socialism, each somewhat differently. From their debates emerged a socialist Zionist movement, which split into factions, and then a socialist religious Zionist movement, Mizrahi; and this movement developed detractors who thought that it was either too religious or too socialist. By the early years of 1900, the Zionist movement was intellectually vibrant and ideologically differentiated, already sporting political parties that advocated a variety of ways to fulfill Zionist aspirations: socialist, Marxist, secular, religious, working the land either with or without Arab labor, returning to work the land, or choosing to live and build Jewish cities (Tel Aviv 1909), settling in rural areas and establishing communal or collective farms (kibbutzim), and then combinations evolved, such as religious or secular kibbutzim. Within two decades of founding the WZO, Jews were immigrating from Yemen as well as from eastern and western Europe, WZO offices were established in Jaffa, and other organizations were established to assist in Jewish immigration and settlement. A proliferation of how Zionism should be defined, followed, implemented, and supported emerged in the two decades after the WZOs founding. In 1917, when the British issued the Balfour Declaration and sanctioned great power support for the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine, the two early strands of practical and political Zionism were blended. Practical work of immigrating Zionists and returning to the land evolved along with the political support of a great power. The British sanctioned developing the Jewish national home and channeled Zionism’s diverse outlooks into a collective undertaking to build a presence. In another thirty years in 1947-48, David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister, noted in Israel’s Declaration of Independence in May 1948 that Herzl’s vision of the Jewish State, proclaimed the right of the Jewish people to national revival in their own country. Herzl and his followers wanted to take control of Jewish destiny by shaping a place of their own; his followers bumped along that path, stymied and sometimes slowed, but they plodded forward, sometimes some thought only about their own needs and aspirations, others considering the Arab population in their midst.

-Ken Stein, June 2010

No one can deny the gravity of the situation of the Jews. Wherever they live in perceptible numbers, they are more or less persecuted. Their equality before the law, granted by statute, has become practically a dead letter. They are debarred from filling even moderately high positions, either in the army, or in any public or private capacity. And attempts are made to thrust them out of business also: “Don’t buy from Jews!”

Attacks in Parliaments, in assemblies, in the press, in the pulpit, in the street, on journeys- -for example, their exclusion from certain hotels–even in places of recreation, become daily more numerous. The forms of persecution vary according to the countries and social circles in which they occur. In Russia, imposts are levied on Jewish villages; in Rumania, a few persons are put to death; in Germany, they get a good beating occasionally; in Austria, Anti-Semites exercise terrorism over all public life; in Algeria, there are traveling agitators; in Paris, the Jews are shut out of the so-called best social circles and excluded from clubs. Shades of anti-Jewish feeling are innumerable. But this is not to be an attempt to make out a doleful category of Jewish hardships.

I do not intend to arouse sympathetic emotions on our behalf. That would be foolish, futile, and an undignified proceeding. I shall content myself with putting the following questions to the Jews: Is it not true that, in countries where we live in perceptible numbers, the position of Jewish lawyers, doctors, technicians, teachers, and employees of all descriptions becomes daily more intolerable? Is it not true, that the Jewish middle classes are seriously threatened? Is it not true, that the passions of the mob are incited against our wealthy people? Is it not true, that our poor endure greater sufferings than any other proletariat? I think that this external pressure makes itself felt everywhere. In our economically upper classes it causes discomfort, in our middle classes continual and grave anxieties, in our lower classes absolute despair.

Everything tends, in fact, to one and the same conclusion, which is clearly enunciated in that classic Berlin phrase: “Juden Raus” (Out with the Jews!)

I shall now put the Question in the briefest possible form: Are we to “get out” now and where to? Or, may we yet remain? And how long?

Let us first settle the point of staying where we are. Can we hope for better days, can we possess our souls in patience, can we wait in pious resignation till the princes and peoples of this earth are more mercifully disposed towards us? I say that we cannot hope for a change in the current of feeling. And why not? Even if we were as near to the hearts of princes as are their other subjects, they could not protect us. They would only feel popular hatred by showing us too much favor. By “too much,” I really mean less than is claimed as a right by every ordinary citizen, or by every race. The nations in whose midst Jews live are all either covertly or openly Anti-Semitic.

The common people have not, and indeed cannot have, any historic comprehension. They do not know that the sins of the Middle Ages are now being visited on the nations of Europe. We are what the Ghetto made us. We have attained pre-eminence in finance, because mediaeval conditions drove us to it. The same process is now being repeated. We are again being forced into finance, now it is the stock exchange, by being kept out of other branches of economic activity. Being on the stock exchange, we are consequently exposed afresh to contempt. At the same time we continue to produce an abundance of mediocre intellects who find no outlet, and this endangers our social position as much as does our increasing wealth. Educated Jews without means are now rapidly becoming Socialists. Hence we are certain to suffer very severely in the struggle between classes, because we stand in the most exposed position in the camps of both Socialists and capitalists.

Previous Attempts at a Solution

The artificial means heretofore employed to overcome the troubles of Jews have been either too petty — such as attempts at colonization — or attempts to convert the Jews into peasants in their present homes. What is achieved by transporting a few thousand Jews to another country? Either they come to grief at once, or prosper, and then their prosperity creates Anti-Semitism. We have already discussed these attempts to divert poor Jews to fresh districts. This diversion is clearly inadequate and futile, if it does not actually defeat its own ends; for it merely protracts and postpones a solution, and perhaps even aggravates difficulties.

Whoever would attempt to convert the Jew into a husbandman would be making an extraordinary mistake. For a peasant is in a historical category, as proved by his costume which in some countries he has worn for centuries; and by his tools, which are identical with those used by his earliest forefathers. His plough is unchanged; he carries the seed in his apron; mows with the historical scythe, and threshes with the time-honored flail. But we know that all this can be done by machinery. The agrarian question is only a question of machinery. America must conquer Europe, in the same way as large landed possessions absorb small ones. The peasant is consequently a type which is in course of extinction. Whenever he is artificially preserved, it is done on account of the political interests which he is intended to serve. It is absurd, and indeed impossible, to make modern peasants on the old pattern. No one is wealthy or powerful enough to make civilization take a single retrograde step. The mere preservation of obsolete institutions is a task severe enough to require the enforcement of all the despotic measures of an autocratically governed State.

Are we, therefore, to credit Jews who are intelligent with a desire to become peasants of the old type? One might just as well say to them: “Here is a cross-bow: now go to war!” What? With a cross-bow, while the others have rifles and long range guns? Under these circumstances the Jews are perfectly justified in refusing to stir when people try to make peasants of them. A cross-bow is a beautiful weapon, which inspires me with mournful feelings when I have time to devote to them. But it belongs by rights to a museum. Now, there certainly are districts to which desperate Jews go out, or at any rate, are willing to go out and till the soil. And a little observation shows that these districts — such as the enclave of Hesse in Germany, and some provinces in Russia — these very districts are the principal seats of Anti-Semitism.

For the world’s reformers, who send the Jews to the plough, forget a very important person, who has a great deal to say on the matter. This person is the agriculturist, and the agriculturist is also perfectly justified. For the tax on land, the risks attached to crops, the pressure of large proprietors who cheapen labor, and American competition in particular, combine to make his life hard enough. Besides, the duties on corn cannot go on increasing indefinitely. Nor can the manufacturer be allowed to starve; his political influence is, in fact, in the ascendant, and he must therefore be treated with additional consideration.

All these difficulties are well known, therefore I refer to them only cursorily. I merely wanted to indicate clearly how futile had been past attempts — most of them well intentioned — to solve the Jewish Question. Neither a diversion of the stream, nor an artificial depression of the intellectual level of our proletariat, will overcome the difficulty. The supposed infallible expedient of assimilation has already been dealt with. We cannot get the better of Anti-Semitism by any of these methods. It cannot die out so long as its causes are not removed. Are they removable?

Causes of Anti-Semitism

We shall not again touch on those causes which are a result of temperament, prejudice and narrow views, but shall here restrict ourselves to political and economical causes alone. Modern Anti-Semitism is not to be confounded with the religious persecution of the Jews of former times. It does occasionally take a religious bias in some countries, but the main current of the aggressive movement has now changed. In the principal countries where Anti-Semitism prevails, it does so as a result of the emancipation of the Jews. When civilized nations awoke to the inhumanity of discriminatory legislation and enfranchised us, our enfranchisement came too late. It was no longer possible to remove our disabilities in our old homes. For we had, curiously enough, developed while in the Ghetto into a bourgeois people, and we stepped out of it only to enter into fierce competition with the middle classes. Hence, our emancipation set us suddenly within this middle- class circle, where we have a double pressure to sustain, from within and from without. The Christian bourgeoisie would not be unwilling to cast us as a sacrifice to Socialism, though that would not greatly improve matters.

At the same time, the equal rights of Jews before the law cannot be withdrawn where they have once been conceded. Not only because their withdrawal would be opposed to the spirit of our age, but also because it would immediately drive all Jews, rich and poor alike, into the ranks of subversive parties. Nothing effectual can really be done to our injury. In olden days our jewels were seized. How is our movable property to be got hold of now? It consists of printed papers which are locked up somewhere or other in the world, perhaps in the coffers of Christians. It is, of course, possible to get at shares and debentures in railways, banks and industrial undertakings of all descriptions by taxation, and where the progressive income-tax is in force all our movable property can eventually be laid hold of. But all these efforts cannot be directed against Jews alone, and wherever they might nevertheless be made, severe economic crises would be their immediate consequences, which would be by no means confined to the Jews who would be the first affected. The very impossibility of getting at the Jews nourishes and embitters hatred of them. Anti- Semitism increases day by day and hour by hour among the nations; indeed, it is bound to increase, because the causes of its growth continue to exist and cannot be removed. Its remote cause is our loss of the power of assimilation during the Middle Ages; its immediate cause is our excessive production of mediocre intellects, who cannot find an outlet downwards or upwards — that is to say, no wholesome outlet in either direction. When we sink, we become a revolutionary proletariat, the subordinate officers of all revolutionary parties; and at the same time, when we rise, there rises also our terrible power of the purse.

Effects of Anti-Semitism

The oppression we endure does not improve us, for we are not a whit better than ordinary people. It is true that we do not love our enemies; but he alone who can conquer himself dare reproach us with that fault. Oppression naturally creates hostility against oppressors, and our hostility aggravates the pressure. It is impossible to escape from this eternal circle.

“No!” Some soft-hearted visionaries will say: “No, it is possible! Possible by means of the ultimate perfection of humanity.”

Is it necessary to point to the sentimental folly of this view? He who would found his hope for improved conditions on the ultimate perfection of humanity would indeed be relying upon a Utopia referred previously to our “assimilation”. I do not for a moment wish to imply that I desire such an end. Our national character is too historically famous, and, in spite of every degradation, too fine to make its annihilation desirable. We might perhaps be able to merge ourselves entirely into surrounding races, if these were to leave us in peace for a period of two generations. But they will not leave us in peace. For a little period they manage to tolerate us, and then their hostility breaks out again and again. The world is provoked somehow by our prosperity, because it has for many centuries been accustomed to consider us as the most contemptible among the poverty- stricken. In its ignorance and narrowness of heart, it fails to observe that prosperity weakens our Judaism and extinguishes our peculiarities. It is only pressure that forces us back to the parent stem; it is only hatred encompassing us that makes us strangers once more. Thus, whether we like it or not, we are now, and shall henceforth remain, a historic group with unmistakable characteristics common to us all.

We are one people–our enemies have made us one without our consent, as repeatedly happens in history. Distress binds us together, and, thus united, we suddenly discover our strength. Yes, we are strong enough to form a State, and, indeed, a model State. We possess all human and material resources necessary for the purpose.

This is therefore the appropriate place to give an account of what has been somewhat roughly termed our “human material.” But it would not be appreciated till the broad lines of the plan, on which everything depends, has first been marked out.

The Plan

The whole plan is in its essence perfectly simple, as it must necessarily be if it is to come within the comprehension of all.

Let the sovereignty be granted to us over a portion of the globe large enough to satisfy the rightful requirements of a nation; the rest we shall manage for ourselves.

The creation of a new State is neither ridiculous nor impossible. We have in our day witnessed the process in connection with nations which were not largely members of the middle class, but poorer, less educated, and consequently weaker than ourselves. The Governments of all countries scourged by Anti-Semitism will be keenly interested in assisting us to obtain the sovereignty we want.

The plan, simple in design, but complicated in execution, will be carried out by two agencies: The Society of Jews and the Jewish Company. The Society of Jews will do the preparatory work in the domains of science and politics, which the Jewish Company will afterwards apply practically. The Jewish Company will be the liquidating agent of the business interests of departing Jews, and will organize commerce and trade in the new country.

We must not imagine the departure of the Jews to be a sudden one. It will be gradual, continuous, and will cover many decades. The poorest will go first to cultivate the soil. In accordance with a preconceived plan, they will construct roads, bridges, railways and telegraph installations; regulate rivers; and build their own dwellings; their labor will create trade, trade will create markets and markets will attract new settlers, for every man will go voluntarily, at his own expense and his own risk. The labor expended on the land will enhance its value, and the Jews will soon perceive that a new and permanent sphere of operation is opening here for that spirit of enterprise which has heretofore met only with hatred and obloquy.

If we wish to found a State today, we shall not do it in the way which would have been the only possible one a thousand years ago. It is foolish to revert to old stages of civilization, as many Zionists would like to do. Supposing, for example, we were obliged to clear a country of wild beasts, we should not set about the task in the fashion of Europeans of the fifth century. We should not take spear and lance and go out singly in pursuit of bears; we would organize a large and active hunting party, drive the animals together, and throw a melinite bomb into their midst.

If we wish to conduct building operations, we shall not plant a mass of stakes and piles on the shore of a lake, but we shall build as men build now. Indeed, we shall build in a bolder and more stately style than was ever adopted before, for we now possess means which men never yet possessed.

The emigrants standing lowest in the economic scale will be slowly followed by those of a higher grade. Those who at this moment are living in despair will go first. They will be led by the mediocre intellects which we produce so superabundantly and which are persecuted everywhere.

This pamphlet will open a general discussion on the Jewish Question, but that does not mean that there will be any voting on it. Such a result would ruin the cause from the outset, and dissidents must remember that allegiance or opposition is entirely voluntary. He who will not come with us should remain behind.

Let all who are willing to join us, fall in behind our banner and fight for our cause with voice and pen and deed.

Those Jews who agree with our idea of a State will attach themselves to the Society, which will thereby be authorized to confer and treat with Governments in the name of our people. The Society will thus be acknowledged in its relations with Governments as a State-creating power. This acknowledgment will practically create the State.

Should the Powers declare themselves willing to admit our sovereignty over a neutral piece of land, then the Society will enter into negotiations for the possession of this land. Here two territories come under consideration, Palestine and Argentine. In both countries important experiments in colonization have been made, though on the mistaken principle of a gradual infiltration of Jews. An infiltration is bound to end badly. It continues till the inevitable moment when the native population feels itself threatened, and forces the Government to stop a further influx of Jews. Immigration is consequently futile unless we have the sovereign right to continue such immigration.

The Society of Jews will treat with the present masters of the land, putting itself under the protectorate of the European Powers, if they prove friendly to the plan. We could offer the present possessors of the land enormous advantages, assume part of the public debt, build new roads for traffic, which our presence in the country would render necessary, and do many other things. The creation of our State would be beneficial to adjacent countries, because the cultivation of a strip of land increases the value of its surrounding districts in innumerable ways.

[1] Anna and Max Nordau, Max Nordau A Biography, New York, 1943, p. 118.

[2] Alex Bein, Theodore Herzl, Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1940, pp. 114-116.

[3] Shlomo Avineri, “Theodore Herzl’s Diaries as Bildungsroman,” Jewish Social Studies, Vol. 5, No.3 (1999), pp. 1-46.