Reform Rabbinical Conference Ends in Frankfurt

July 28, 1845

Thirty-one rabbis meet in Frankfurt-am-Main for a two-week assembly, the second of three rabbinic meetings that took place in Germany during the 1840s.

The first major discussion was about the use of Hebrew in religious services. Some felt that Hebrew held a special place in the Jewish soul even if knowledge of the language was in decline. Others felt that congregants would be more responsive to prayers in their native tongue, German. The assembly ultimately decided that while Jewish law allows prayer in any language, it was necessary to recite certain prayers, including the Barechu and Shema, in Hebrew. The rest of the service could be in German.

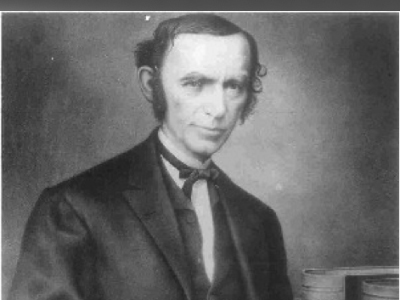

This second major discussion is about messianism and prayers regarding the return of the Jewish people to the Land of Israel. Rabbi David Einhorn argues that while the messianic idea is still essential, Judaism’s mission is no longer a return to the Land of Israel. He says:

The collapse of Israel’s political independence was once regarded as a misfortune, but it really represented progress, not atrophy but an elevation of religion. Henceforth Israel came closer to its destiny. Holy devotion replaced sacrifices. Israel was to bear the word of G-d to all the corners of the earth. (Michael A. Meyer, Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988, p. 138)

The decision to remove prayers calling for the return to Israel was unanimous, implying that Judaism was a religion and not a nationality. The assembly believed removing such prayers was a necessary prerequisite to civic equality.