HMG White Paper: Statement of Policy

(May 1939)

Hurewitz, J.C. The Middle East and North Africa in World Politics, British- French Supremacy, 1914- 1945. Vol. 2. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979. 532-38. Print

The 1939 White Paper on Palestine was a watershed document in the history of the Jewish national home. During the previous two decades, Zionists had enjoyed the relatively unimpeded development of autonomous state-building. The White Paper sanctioned restrictions on Jewish physical and demographic development, and was an abrupt change of tone from what the British had favored in the Balfour Declaration and the Articles of the Mandate – both of which had provided the Zionists privileged status in Palestine.

The decade of the 1930s in Palestine witnessed prolonged Arab violence against the British and Zionists, and Britain finally decided to virtually stop the growth of a Jewish State.

The core of the 1939 White Paper was Britain’s readiness to relegate the Jewish presence in Palestine to a minority in a future majority Arab state. Immigration and land purchase restrictions were applied to Jewish development. After the restoration of law and order in Palestine, Britain would establish a transition period in which Palestinian Arabs would increase their participation in self-government, again with British advisers. Within ten years, a unitary or federal Arab-Jewish state would be established. As a result of the White Paper and its proposed application, the Zionist goal of creating a homeland or state with a Jewish majority looked like it might end. The promise of the Balfour Declaration, Britain’s support for the development of the Jewish national home, was overturned. However, when the Palestinian leadership, led by the Mufti of Jerusaelm, was inclined to accept a majority Arab state in ten years, he rejected the idea.

Britain altered its policy in Palestine to end the violence there and to appease Arab leaders in surrounding Arab states. Not only would Jewish immigration be restricted to 75,000 people over the coming five years, but, “No Further Jewish immigration was to be permitted unless the Arabs of Palestine were prepared to agree to it.” Additionally, Jewish land purchase in Palestine was severely curtailed. Now divided into three sectors, the majority of cultivable land was off limits for Jewish purchase unless the British High Commissioner gave consent. In regard to land, Britain excercised a paternalistic policy over the Arabs of Palestine, acknowledging, as did Sir John Shuckburgh of the Colonial Office, that “the Arab landowner [needed] to be protected against himself.” [1]

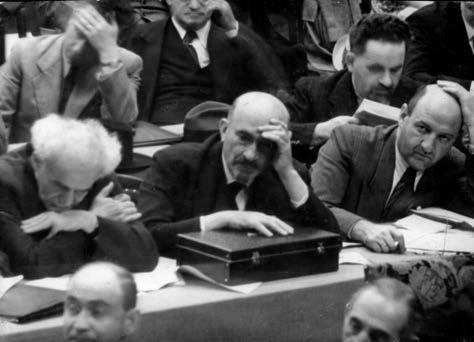

The contents of the White Paper emerged out of the February 1939 St. James (London) Conference. Actually, two parallel conferences took place, as Palestinian Arabs refused to sit at the same table and negotiate with the Jewish delegation. In fact, Britain had entered the conference knowing its outcome would be to curtail Jewish development, even though there was the appearance of consultation. The White Paper’s announcement came just three months after Kristallnacht (November 1938), when pogrom-like attacks were unleashed against Jewish life, property, and synagogues throughout Austria and Germany. The juxtaposition of British policy emerging strictly from concerns of its strategic interests in the Middle East was caught up with events in Europe, and the Zionists saw the restrictions on the Jewish national home at this point as particularly offensive, as the key immigration life-line for Jews from Europe to Palestine was all but cut.

While the official nature of the White Paper was a stirring blow to the Zionists, its contents were not unexpected. The White Paper sharpened the growing discord between David Ben-Gurion, Chairman of the Jewish Agency Executive, and Chaim Weizmann, President of the World Zionist Organization. Despite the White Paper, Ben-Gurion wanted to immigrate as many Jews as quickly as possible through legal and illegal means. He worked to acquire ships for their passage, to form a Jewish navy, to raise money to purchase land offered for sale by Arabs in Palestine, and to find ways to maintain control over the strategically important Haifa port.

Upon the conclusion of the St. James Conference, Ben-Gurion told British Prime Minister Malcolm MacDonald that Zionist affairs were wrapping up in London. This was a not- so-oblique reference to his decision to shift the center of political activity to the United States, where the White House could put pressure on Great Britain. Zionist political activity, nascent in America, now became a key focal point. An office of the Jewish Agency/World Zionist Organization was set up in Washington; its purposes included educating and lobbying the American Congress and Executive Branch, soliciting support from the American press, and engaging Jewish America in the Zionist cause. The culmination of Ben-Gurion’s move away from sole reliance on Great Britain to opening a key political front in the United States came in May 1942 (See Biltmore Conference). From 1939 to 1944, the White Paper pushed Ben-Gurion to adopt a tzionut lohemet (fighting Zionism) policy. It distanced him from Chaim Weizmann, who favored the use of diplomacy and preferred continued strong relations with Britain, and especially with Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

In September 1939, Ben-Gurion expressed the complexity of Zionist policy to Britain in his famous statement, “we must help the [British] army as if there were no White Paper, and we must fight the White Paper as if there were no war.” Several days after this remark, Ben-Gurion laid out his political vision of “advancement toward the creation of a Hebrew state in Palestine.” It was an outline for a policy he would pursue throughout the 1940s. Jewry in Palestine and in America was galvanized to fight the White Paper in word and deed. Zionists redoubled their efforts to circumvent the restrictions. The White Paper did not curb the Zionist commitment to create an independent Jewish homeland, state, or commonwealth. Some Jewish immigration and land purchase did occur, despite the White Paper’s restrictions. Not able to spend sums of money to bring thousands of immigrants to Palestine, Zionists made allocations and directed funds toward building the economic and physical infrastructure of Jewish areas in Palestine, which contributed to Zionist economic wellbeing after the war’s conclusion.

During World War II, American and British policy toward Zionism was almost always judged by whether the 1939 White Paper’s restrictions on immigration could or should be suspended. In seeking to rescue Jews from Rumania in February 1943 and Hungary in May and July 1944, serious German proposals were offered to exchange Jews for money or supplies, but were not carried out for fear “that acceptance of such an offer would let loose on the West a flood of immigrants who would exert an unacceptable strain on resources, with grave political repercussions because of the White Paper…the [British] Foreign office retreated behind its fear of exceeding the decreed current immigration levels into Palestine.” [2]. Despite immigration restrictions, illegal Jewish immigration to Palestine continued, and even with only limited success, the continued trickle of desperate Jews from Europe galvanized the Zionist community in Palestine to press forward toward solidifying a national home. Devastation in Europe, Arab opposition in Palestine and in the rest of the Middle East to a political Jewish presence, and anti-Zionist British policy collectively challenged the perseverance of the Zionist enterprise. Strain in post war British-American relations occurred over the issue of Jewish immigration to Palestine. At the end of WWII, U.S. President Truman advocated opening the gates of Palestine to 100,000 immigrants, a position disputed by British Foreign Secretary Bevin.

One of the first acts of the new Jewish state in May 1948 was the cancellation of the 1939 White Paper. Why? Israel insisted on controlling the prerogative of immigration, a life and death issue that had prevented Jews from finding safe refuge in the 1930s and 1940s. The legal cancellation of all immigration restrictions for Jews was reformulated in July 1950 when the Israeli parliament passed the “Law of Return” (Hok Hasvut). It gave anyone in the world with appropriate Jewish ancestry the prerogative to immigrate to Israel and become a citizen of the state.

–Ken Stein, May 2010

- In the Statement on Palestine, issued on 9 November 1938, His Majesty’s Government announced their intention to invite representatives of the Arabs of Palestine, of certain neighboring countries, and of the Jewish Agency to confer with them in London regarding future policy. It was their sincere hope that, as a result of full, free, and frank discussion, some understanding might be reached. Conferences recently took place with Arab and Jewish Delegations lasting for a period of several weeks, and served the purpose of a complete exchange of views between British Ministers and the Arab and Jewish representatives. In the light of the discussions as well as of the situation in Palestine and of the Reports of the Royal Commission and the Partition Commission,certain proposals were formulated by His Majesty’s Government and were laid before the Arab and Jewish Delegations as the basis of an agreed settlement. Neither the Arab nor the Jewish Delegation felt able to accept these proposals, and the Conferences, therefore, did not result in an agreement. Accordingly, His Majesty’s Government are free to formulate their own policy, and after careful consideration, they have decided to adhere generally to the proposals which were finally submitted to, and discussed with, the Arab and Jewish Delegations.

- The Mandate for Palestine, the terms of which were confirmed by the Council of the League of Nations in 1922, has governed the policy of successive British Governments for nearly twenty years. It embodies the Balfour Declaration and imposes on the Mandatory four main obligations… There is no dispute regarding the interpretation of one of these obligations, that touching the protection of and access to the Holy Places and religious buildings or sites. The other three main obligations are generally as follows:

- To place the country under such political, administrative, and economic conditions as will secure the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people, to facilitate Jewish immigration under suitable conditions, and to encourage, in co-operation with the Jewish Agency, close settlement by Jews on the land.

- To safeguard the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine irrespective of race and religion, and, whilst facilitating Jewish immigration and settlement, to ensure that the rights and positions of other sections of the population are not prejudiced.

- To place the country under such political, administrative, and economic conditions as will secure the development of self-governing institutions.

- The Royal Commission and previous Commissions of Enquiry have drawn attention to the ambiguity of certain expressions in the Mandate, such as the expression “a National Home for the Jewish people,” and they have found in this ambiguity and the resulting uncertainty as to the objectives of policy a fundamental cause of unrest and hostility between Arabs and Jews. His Majesty’s Government are convinced that in the interests of the peace and well-being of the whole people of Palestine a clear definition of policy and objectives is essential. The proposal of partition recommended by the Royal Commission and would have afforded such clarity, but the establishment of self-supporting, independent Arab and Jewish States within Palestine had been found to be impracticable. It has, therefore, been necessary for His Majesty’s Government to devise an alternate policy which will, consistently with their obligations to Arabs and Jews, meet the needs of the situation in Palestine. Their views and proposals are set forth below under the three heads: I. The Constitution, II. Immigration, and III. Land.

I. The Constitution

- It has been urged that the expression “a National Home for the Jewish people” offered a prospect that Palestine might in due course become a Jewish State or Commonwealth. His Majesty’s Government do not wish to contest the view, which was expressed by the Royal Commission, that the Zionist leaders at the time of the issue of the Balfour Declaration recognized that an ultimate Jewish State was not precluded by the terms of the Declaration. But, with the Royal Commission, His Majesty’s Government believed that the framers of the Mandate in which the Balfour Declaration was embodied could not have intended that Palestine should be converted into a Jewish State against the will of the Arab population of the country. That Palestine was not to be converted into a Jewish State might be held to be implied in the passage from the Command Paper of 1922 which reads as follows:

“Unauthorized statements have been made to the effect that the purpose in view is to create a wholly Jewish Palestine. Phrases have been used such as that ‘Palestine is to become as Jewish as England is English.’ His Majesty’s Government regard any such expectation as impracticable and have no such aim in view. Nor have they at any time contemplated … the disappearance or the subordination of the Arabic population, language, or culture in Palestine. They would draw attention to the fact that the terms of the (Balfour) Declaration referred to do not contemplate that Palestine as a whole should be converted into a Jewish National Home, but that such a Home should be founded in Palestine.”

But this statement has not removed doubts, and His Majesty’s Government, therefore, now declare unequivocally that it is not part of their policy that Palestine should become a Jewish State. They would indeed regard it as contrary to their obligations to the Arabs under the Mandate, as well as to the assurances which have been given to the Arab people in the past, that the Arab population of Palestine should be made the subjects of a Jewish State against their will.

- The nature of the Jewish National Home in Palestine was further described in the Common Paper of 1922 as follows:

“During the last two or three generations, the Jews have recreated in Palestine a community, now numbering 80,000, of whom about one-fourth are farmers or workers upon the land. This community has its own political organs; an elected assembly for the direction of its domestic concerns; elected councils in the towns; and an organization for the control of its schools. It has its elected Chief Rabbinate and Rabbinical Council for the direction of its religious affairs. Its business is conducted in Hebrew as a vernacular language, and a Hebrew Press serves its needs. It has its distinctive intellectual life and displays considerable economic activity. This community, then, with its town and country population, its political, religious, and social organizations, its own language, its own customs, its own life, has in fact ‘national’ characteristics. When it is asked what is meant by the development of the Jewish National Home in Palestine, it may be answered that it is not the imposition of a Jewish nationality upon the inhabitants of Palestine as a whole, but the further development of the existing Jewish community, with the assistance of Jews in other parts of the world, in order that it may become a center in which the Jewish people as a whole may take, on grounds of religion and race, an interest and a pride. But in order that this community should have the best prospect of free development and provide a full opportunity for the Jewish people to display its capacities, it is essential that it should know that it is in Palestine as of right and not on sufferance. That is the reason why it is necessary that the existence of a National Jewish Home in Palestine should be internationally guaranteed, and that it should be formally recognized to rest upon ancient historic connection.”

- His Majesty’s Government adhere to this interpretation of the Declaration of 1917 and regard it as an authoritative and comprehensive description of the character of the Jewish National Home in Palestine. It envisaged the further development of the existing Jewish community with the assistance of Jews in other parts of the world. Evidence that His Majesty’s Government have been carrying out their obligation in this respect is to be found in the facts that, since the statement of 1922 was published, more than 300,000 Jews have immigrated to Palestine, and that the population of the National Home has risen to some 450,000, or approaching a third of the entire population of the country. Nor has the Jewish community failed to take full advantage of the opportunities given to it. The growth of the Jewish National Home and its achievements in many fields are a remarkable constructive effort which must command the admiration of the world and must be, in particular, a source of pride to the Jewish people.

- In the recent discussions, the Arab Delegations have repeated the contention that Palestine was included within the area in which Sir Henry McMahon, on behalf of the British Government, in October 1915, undertook to recognize and support Arab independence. The validity of this claim, based on the terms of the correspondence which passed between Sir Henry McMahon and the Sherif of Mecca, was thoroughly and carefully investigated by British and Arab representatives during the recent Conferences in London. Their Report, which has been published, states that both the Arab and the British representatives endeavored to understand the point of view of the other party but that they were unable to reach agreement upon an interpretation of the correspondence. There is no need to summarize here the arguments presented by each side. His Majesty’s Government regret the misunderstandings which have arisen as regards some of the phrases used. For their part, they can only adhere, for the reasons given by their representatives in the Report, to the view that the whole of Palestine west of Jordan was excluded from Sir Henry McMahon’s pledge, and they, therefore, cannot agree that the McMahon correspondence forms a just basis for the claim that Palestine should be converted into an Arab State.

- His Majesty’s Government are charged as the Mandatory authority “to secure the development of self-governing institutions” in Palestine. Apart from this specific obligation, they would regard it as contrary to the whole spirit of the Mandate system that the population of Palestine should remain forever under Mandatory tutelage. It is proper that the people of the country should, as early as possible, enjoy the rights of self-government which are exercised by the people of neighboring countries. His Majesty’s Government are unable at present to foresee the exact constitutional forms which government in Palestine will eventually take, but their objective is self-government, and they desire to see established ultimately an independent Palestine State. It should be a State in which the two peoples in Palestine, Arabs and Jews, share authority in government in such a way that the essential interests of each are secured.

- The establishment of an independent State and the complete relinquishment of Mandatory control in Palestine would require such relations between the Arabs and the Jews as would make good government possible. Moreover, the growth of self-governing institutions in Palestine, as in other countries, must be an evolutionary process. A transitional period will be required before independence is achieved, throughout which ultimate responsibility for the Government of the country will be retained by His Majesty’s Government as the Mandatory authority, while the people of the country are taking an increasing share in the Government, and understanding and cooperation amongst them are growing. It will be the constant endeavor of His Majesty’s Government to promote good relations between the Arabs and the Jews.

- In the light of these considerations, His Majesty’s Government make the following declaration of their intentions regarding the future government of Palestine:

- The objective of His Majesty’s Government is the establishment within ten years of an independent Palestine State in such treaty relations with the United Kingdom as will provide satisfactorily for the commercial and strategic requirements of both countries in the future. This proposal for the establishment of the independent State would involve consultation with the Council of the League of Nations with a view to the termination of the Mandate.

- The independent State should be one in which Arabs and Jews share in government in such a way as to ensure that the essential interests of each community are safeguarded.

- The establishment of the independent State will be preceded by a transitional period throughout which His Majesty’s Government will retain responsibility for the government of the country. During the transitional period, the people of Palestine will be given an increasing part in the government of their country. Both sections of the population will have an opportunity to participate in the machinery of government, and the process will be carried on whether or not they both avail themselves of it.

- As soon as peace and order have been sufficiently restored in Palestine, steps will be taken to carry out this policy of giving the people of Palestine an increasing part in the government of their country, the objective being to place Palestinians in charge of all the Departments of Government, with the assistance of British advisers and subject to the control of the High Commissioner. With this object in view, His Majesty’s Government will be prepared immediately to arrange that Palestinians shall be placed in charge of certain Departments, with British advisers. The Palestinian heads of Departments will sit on the Executive Council, which advises the High Commissioner. Arab and Jewish representatives will be incited to serve as heads of Departments approximately in proportion to their respective populations. The number of Palestinians in charge of Departments will be increased as circumstances permit until all heads of Departments are Palestinians, exercising the administrative and advisory functions which are at present performed by British officials. When that stage is reached, consideration will be given to the question of converting the Executive Council into a Council of Ministers with a consequential change in the status and functions of the Palestinian heads of Departments.

- His Majesty’s Government make no proposals at this stage regarding the establishment of an elective legislature. Nevertheless, they would regard this as an appropriate constitutional development, and, should public opinion in Palestine hereafter show itself in favor of such a development, they will be prepared, provided that local conditions permit, to establish the necessary machinery.

- At the end of five years from the restoration of peace and order, an appropriate body representative of the people of Palestine and of His Majesty’s Government will be set up to review the working of the constitutional arrangements during the transitional period and to consider and make recommendations regarding the Constitution of the independent Palestine State.

- His Majesty’s Government will require to be satisfied that in the treaty contemplated by sub-paragraph [a.] or in the Constitution contemplated by sub-paragraph [d.] adequate provision has been made for:

- The security of, and freedom of access to, the Holy Places, and the protection of the interests and property of the various religious bodies;

- The protection of the different communities in Palestine in accordance with the obligations of His Majesty’s Government to both Arabs and Jews and for the special position in Palestine of the Jewish National Home;

- Such requirements to meet the strategic situation as may be regarded as necessary by His Majesty’s Government in the light of the circumstances then existing.

- His Majesty’s Government will also require to be satisfied that the interests of certain foreign countries in Palestine, for the preservation of which they are at present responsible, are adequately safeguarded.

- His Majesty’s Government will do everything in their power to create conditions which will enable the independent Palestine State to come into being within ten years. If, at the end of ten years, it appears to His Majesty’s Government that, contrary to their hope, circumstances require the postponement of the establishment of the independent State, they will consult with representatives of the people of Palestine, the Council of the League of Nations, and the neighboring Arab States before deciding on such a postponement. If His Majesty’s Government come to the conclusion that postponement is unavoidable, they will invite the cooperation of these parties in framing plans for the future with a view to achieving the desired objective at the earliest possible date.

- During the transitional period, steps will be taken to increase the powers and responsibilities of municipal corporations and local councils.

H. Immigration

- Under Article 6 of the Mandate, the Administration of Palestine, “while ensuring that the rights and position of other sections of the population are not prejudiced,” is required to “facilitate Jewish immigration under suitable conditions.” Beyond this, the extent to which Jewish immigration into Palestine is to be permitted is nowhere defined in the Mandate. But in the Command Paper of 1922, it was laid down that for the fulfillment of the policy of establishing a Jewish National Home, “it is necessary that the Jewish community in Palestine should be able to increase its numbers by immigration. This immigration cannot be so great in volume as to exceed whatever may be the economic capacity of the country at the time to absorb new arrivals. It is essential to ensure that the immigrants should not be a burden upon the people of Palestine as a whole, and that they should not deprive any section of the present population of their employment.”

In practice, from that date onwards until recent times, the economic absorptive capacity of the country has been treated as the sole limiting factor, and in the letter which Mr. Ramsay MacDonald, as Prime Minister, sent to Dr. Weizmann in February 1931, it was laid down as a matter of policy that economic absorptive capacity was the sole criterion. This interpretation has been supported by resolutions of the Permanent Mandates Commission. But His Majesty’s Government do not read either the Statement of Policy of 1922 or the letter of 1931 and implying that the Mandate requires them, for all time and in all circumstances, to facilitate the immigration of Jews into Palestine subject only to consideration of the country’s economic absorptive capacity. Nor do they find anything in the Mandate or in subsequent Statements of Policy to support the view that the establishment of a Jewish National Home in Palestine cannot be effected unless immigration is allowed to continue indefinitely. If immigration has an adverse effect on the economic position in the country, it should clearly be restricted; and equally, if it has a seriously damaging effect on the political position in the country, that is a factor that should not be ignored. Although it is not difficult to contend that the large number of Jewish immigrants who have been admitted so far have been absorbed economically, the fear of the Arabs that his influx will continue indefinitely until the Jewish population is in a position to dominate them has produced consequences which are extremely grave for Jews and Arabs alike and for the peace and prosperity of Palestine. The lamentable disturbances of the past three years are only the latest and most sustained manifestation of this intense Arab apprehension. The methods employed by Arab terrorists against fellow Arabs and Jews alike must receive unqualified condemnation. But it cannot be denied that fear of indefinite Jewish immigration is widespread amongst the Arab population and that this fear has made possible disturbances which have given a serious setback to economic progress, depleted the Palestine exchequer, rendered life and property insecure, and produced a bitterness between the Arab and Jewish populations which is deplorable between citizens of the same country. If in these circumstances, immigration is continued up to the economic absorptive capacity of the country, regardless of all other circumstances, a fatal enmity between the two peoples will be perpetuated, and the situation in Palestine may become a permanent source of friction amongst all peoples in the Near and Middle East. His Majesty’s Government cannot take the view that either their obligations under the Mandate, or considerations of common sense and justice, require that they should ignore these circumstances in framing immigration policy.

- In the view of the Royal Commission, the association of the policy of the Balfour Declaration with the Mandate system implied the belief that Arab hostility to the former would sooner or later be overcome. It has been the hope of British Governments ever since the Balfour Declaration was issued that in time, the Arab population, recognizing the advantages to be derived from Jewish settlement and development in Palestine, would become reconciled to the further growth of the Jewish National Home. This hope has not been fulfilled. The alternatives before His Majesty’s Government are either [1] to seek to expand the Jewish National Home indefinitely by immigration, against the strongly expressed will of the Arab people of the country; or [2] to permit further expansion of the Jewish National Home by immigration only if the Arabs are prepared to acquiesce in it. The former policy means rule by force. Apart from other considerations, such a policy seems to His Majesty’s Government to be contrary to the whole spirit of Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, as well as to their specific obligations to the Arabs in the Palestine Mandate. Moreover, the relations between the Arabs and the Jews in Palestine must be based sooner or later on mutual tolerance and goodwill; the peace, security, and progress of the Jewish National Home itself requires this. Therefore, His Majesty’s Government, after earnest consideration, and taking into account the extent to which the growth of the Jewish National Home has been facilitated over the last twenty years, have decided that the time has come to adopt in principle the second of the alternatives referred to above.

- It has urged that all further Jewish immigration into Palestine should be stopped forthwith. His Majesty’s Government cannot accept such a proposal. It would damage the whole of the financial and economic system of Palestine and thus affect adversely the interests of Arabs and Jews alike. Moreover, in the view of His Majesty’s Government, abruptly to stop further immigration would be unjust to the Jewish National Home. But, above all, His Majesty’s Government are conscious of the present unhappy plight of large numbers of Jews who seek a refuge from certain European countries, and they believe that Palestine can and should make a further contribution to the solution of this pressing world problem. In all these circumstances, they believe that they will be acting consistently with their Mandatory obligations to both Arabs and Jews, and in the manner best calculated to serve the interests of the whole people of Palestine by adopting the following proposals regarding immigration:

- Jewish immigration during the next five years will be at a rate which, if economic absorptive capacity permits, will bring the Jewish population up to approximately one-third of the total population of the country. Taking into account the expected natural increase of the Arab and Jewish populations, and the number of illegal Jewish immigrants now in the country, this would allow of the admission, as from the beginning of April this year, of some 75,000 immigrants over the next five years. These immigrants would, subject to the criterion of economic absorptive capacity, be admitted as follows:

- For each of the next five years, a quota of 10,000 Jewish immigrants will be allowed, on the understanding that a shortage in any one year may be added to the quotas for subsequent years, within the five-year period, if economic absorptive capacity permits.

- In addition, as a contribution towards the solution of the Jewish refugee problem, 25,000 refugees will be admitted as soon as the High Commissioner is satisfied that adequate provision for their maintenance is ensured, special consideration being given to refugee children and dependents.

- The existing machinery for ascertaining economic absorptive capacity will be retained, and the High Commissioner will have the ultimate responsibility for deciding the limits of economic capacity. Before each periodic decision is taken, Jewish and Arab representatives will be consulted.

- After the period of five years, no further Jewish immigration will be permitted unless the Arabs of Palestine are prepared to acquiesce in it.

- His Majesty’s Government are determined to check illegal immigration, and further preventive measures are being adopted. The numbers of any Jewish illegal immigrants who, despite these measures, may succeed in coming into the country and cannot be deported will be deducted from the yearly quotas.

- His Majesty’s Government are satisfied that, when the immigration over five years which is now contemplated has taken place, they will not be justified in facilitating, nor will they be under any obligation to facilitate, the further development of the Jewish National Home by immigration regardless of the wishes of the Arab population.

III. Land

- The Administration of Palestine is required, under Article 6 of the Mandate, “while ensuring that the rights and position of other sections of the population are not prejudiced,” to encourage “close settlement by Jews on the land,” and no restriction has been imposed hitherto on the transfer of land from Arabs to Jews. The Reports of several expert Commissions have indicated that, owing to the natural growth of the Arab population and the steady sale in recent years of Arab land to Jews, there is now in certain areas, no room for further transfers of Arab land, whilst in some other areas, such transfers of land must be restricted if Arab cultivators are to maintain their existing standard of life and a considerable landless Arab population is not soon to be created. In these circumstances, the High Commissioner will be given general powers to prohibit and regulate transfers of land. These powers will date from the publication of this Statement of Policy and the High Commissioner will retain them throughout the transitional period.

- The policy of the Government will be directed towards the development of the land and the improvement, where possible, of methods of cultivation. In the light of such development, it will be open to the High Commissioner, should he be satisfied that the “rights and position” of the Arab population will be duly preserved, to review and modify any orders passed relating to the prohibition or restriction of the transfer of land.

- In framing these proposals, His Majesty’s Government have sincerely endeavored to act in strict accordance with their obligations under the Mandate to both the Arabs and the Jews. The vagueness of the phrases employed in some instances to describe these obligations has led to controversy and has made the task of interpretation difficult. His Majesty’s Government cannot hope to satisfy the partisans of one party or the other in such controversy as the Mandate has aroused. Their purpose is to be just as between the two peoples in Palestine whose destinies in that country have been affected by the great events of recent years, and who, since they live side by side, must learn to practice mutual tolerance, good will, and cooperation. In looking to the future, His Majesty’s Government are not blind to the fact that some events of the past make the task of creating these relations difficult; but they are encouraged by the knowledge that at many times and in many places in Palestine during recent years, the Arab and Jewish inhabitants have lived in friendship together. Each community has much to contribute to the welfare of their common land, and each must earnestly desire peace in which to assist in increasing the well-being of the whole people of the country. The responsibility which falls on them, no less than upon His Majesty’s Government, to cooperate together to ensure peace is all the more solemn because their country is revered by many millions of Moslems, Jews, and Christians throughout the world who pray for peace in Palestine and for the happiness of her people.

[1] Remarks by British Colonial Office official, Sir John Shuckburgh, 14 June 1940, CO 733/425/75872, Part 2.

[2] Cohen, Michael J. (ed.) The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann Series A Letters Volume XXI, January 1943-May 1945, Israel University Press (1974), pp. xiv-xv.