Natan Alterman, “Victory as a Scapegoat,” Maariv

Source: https://benyehuda.org/read/14666

One of Israel’s greatest writers, Natan Alterman reminded Israel’s accusers in 1969 that well into the 20th century the Palestinians did not even understand themselves as a separate people with a distinctive national identity marking them off from other Arabs. His argument, if framed as a question, might be formulated along these lines: If no one else, not least the Palestinians’ own ancestors, saw themselves as a distinctive people or nation in Ottoman Palestine, how can the Zionists be blamed for not seeing one either? To fault the Zionists for failing to see what was not yet visible to anyone else, including the Palestinians themselves, is to fault them not for suffering from blindness, but for lacking clairvoyance.

Scott Abramson, March 2025

Background

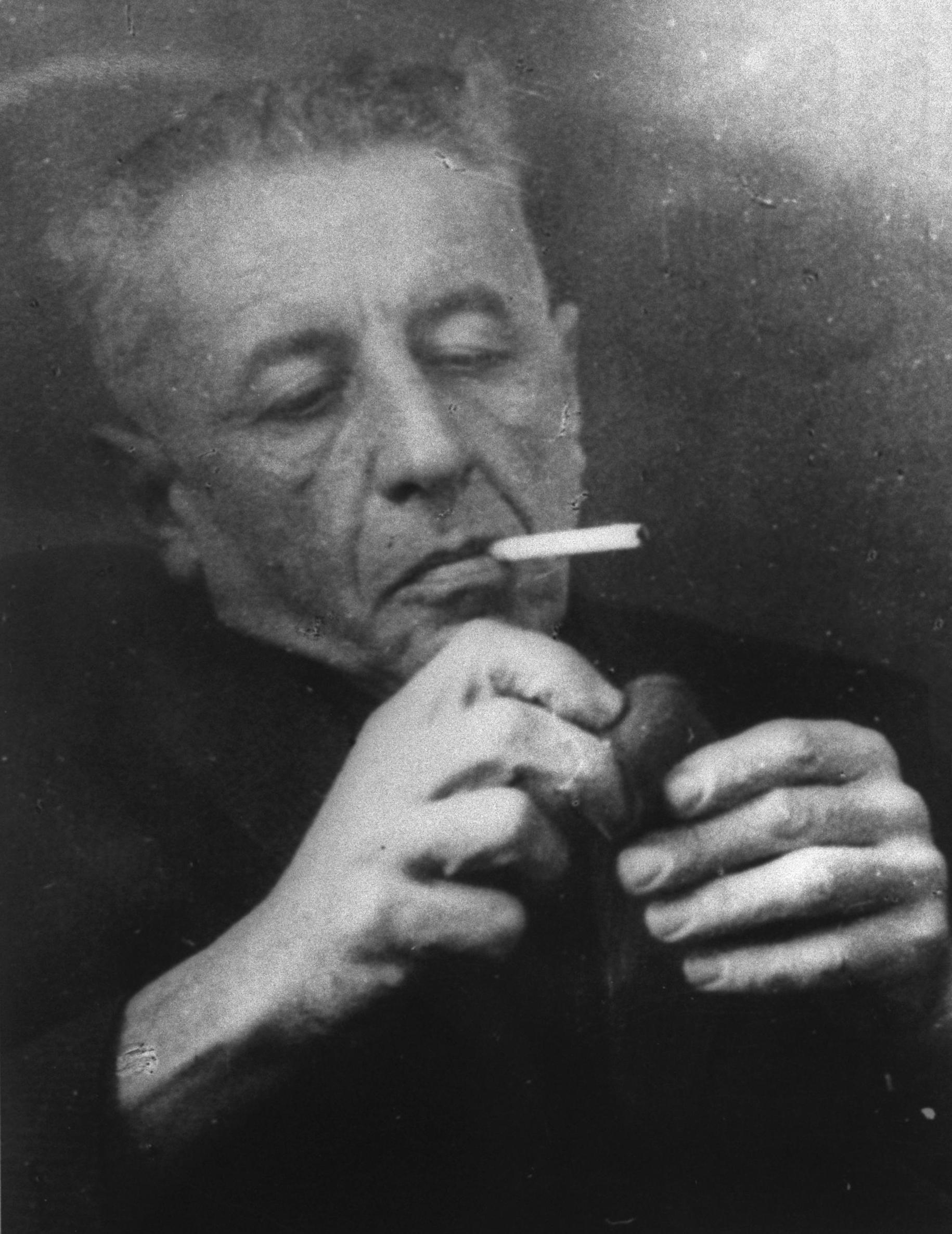

In any list of Israel’s most beloved poets, there can be no doubt that the name Natan Alterman (1910-1970) would number among the top entries. For about two decades (the second half of the British Mandate of Palestine and into the first years of Israeli statehood), Alterman reigned without rival in the kingdom of Hebrew letters.

Alterman was a fiercely political poet, especially as he advanced in age. His widely read

columns in the Israeli newspapers Haaretz and Davar engaged with the issues of the day, and a political controversy or scandal seldom passed without his editorialization in verse. So influential was his voice in the popular conversation that the legendary literary critic Dan Miron even crowned him Israel’s “national spokesman.”

It would be no less appropriate to describe Alterman as his countrymen’s guide through the Israeli national odyssey. On the winding path Israeli history has followed, a path of many ups and downs, Alterman’s poems have stood like signposts marking the major events along the way. To take just one example: Few Israelis, whatever their age, can reflect on the War of Independence without recalling the words of Alterman’s iconic poem “Silver Platter.”

Although Alterman was the quintessential Labor Zionist–the Labor Party’s organ, Davar, carried his column on and off for decades–the Israeli victory in the Six-Day War accelerated what had been a slow rightward drift over the years. Alterman even became a founding member of the postwar intellectual circle that advocated Jewish settlement in the newly conquered territories, the Movement for Greater Israel.1

Two-and-a-half years after the Israeli triumph and less than three months before his death, Alterman wrote the poetic essay below, “Victory as a Scapegoat.” The reader will at once note that many of the essay’s themes are the very same, more than a half-century later, as those in today’s discourse related to Israel. Alterman, for example, broods on Israel’s international isolation. He wrote the essay in the wake of the Six-Day War, when the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, East Germany, Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia all broke off relations with the Jewish state. Then as now, the feeling in Israel was captured by the title of a popular folk song released after the Six-Day War, “The Whole World Is Against Us.” Among the other thematic notes Alterman strikes that still resonate today are the fickleness of American support, Israel’s “image problem,” and Israel’s opponents’ ritual of somehow twisting the country’s successes–and none more than its military triumphs–into sins.

About a third of the essay, though, is a defense of Zionism against the charge that “the prophets of Zionism,” as Alterman calls the movement’s early visionaries, were damningly blind to the existence of the Palestinian Arabs. In rebuttal, Alterman reminds Israel’s accusers that well into the twentieth century the Palestinians did not even understand themselves as a separate people with a distinctive national identity marking them off from other Arabs. His argument, if framed as a question, might be formulated along these lines: If no one else, not least the Palestinians’ own ancestors, saw their own distinctive nation in Ottoman Palestine, how can the Zionists be blamed for not seeing one either? Thus, to fault the Zionists for failing to see what was not yet visible to anyone else, including the Palestinians, is to fault them, not for suffering from blindness, but for lacking clairvoyance.

Scott Abramson, February 26, 2025

Natan Alterman, “Victory as a Scapegoat,” Ma’ariv, December 26, 1969

Source: https://benyehuda.org/read/14666

Israel and, still more so, the Jewish people have known harder times than the present and its American about-face.2

And yet, never in the entire course of our relations with the peoples of the world has there been a time when, in the judgment of the nations, the Jews stood so isolated and bereft of sympathizers, so beleaguered by condemnations and reproaches–as a party that represents injustice or, at best, reprehensible obstinacy, as a party whom it is a mark of humanism and enlightened views to denounce.

We say that it is a question of “image,” and, shocked that our image could be affected, we seek an explanation for this phenomenon. The usual explanation is that it was our victory in the Six-Day War that was our downfall. The world does not like the strong.

This opinion has become so deeply rooted within us, so convenient for us to cling to, that it seems that to validate this convenient opinion, our whole policy has become a kind of healing process to recover from the blow of victory and to devise remedies for it.3 In other words, “Let’s deal wisely with it, lest it multiply.”4

The crux of this let’s-deal-wisely method was that, no matter what happened, we should refrain from any statement, any basic reference, any step, any trace of an action, that could, God forbid, evoke in the heart of anyone the idea that the Six-Day War and its victory had–from the standpoint of the history of the nations, the happenings in the region, the causes of the events and their purpose–some kind of meaning beyond the conquest of Arab territories belonging to Hussein and Nasser.

From all the burdens of our law and our justice,

from all the layers of our history and the history of the region and our place in it,

from all the revivalist, pioneering efforts of the Return to Zion,

from all the different political definitions of these lands since the Balfour Declaration,

through all the incarnations of the Mandate’s borders,

through all the proposals of the commissions of inquiry,

and the political configurations that carved up and changed the maps of the region in the last century…

of all these, we held on to, for convenience, the Security Council’s resolution on the interpretation of our “package.”6

Yet we go round and round like a squirrel spinning in a wheel with a hollow nut in its paw.

What’s more, we are annoyed and surprised that the State Department dares to define our argument as “monotonous.”

Some of us believe, as is well known, that in order to repair our image and to get out of this vicious circle, we must declare that we recognize the existence of the Palestinian people and that the conflict is one between us and them, not between us and the Arab states.

Fortunately for Israel, this is not official doctrine. Fortunately for Israel, we hear from time to time that this is not the position of our government. Not long ago, this was pressed home by Golda Meir in the Knesset. The foreign minister7 even occasionally repeats that there is no place for another Arab state between Israel and the Kingdom of Jordan.

Even so, these official statements do nothing to illustrate the extent to which the idea of a separate Palestinian national and political entity would not only fail to advance a solution, it would strike at the roots of our whole existence and all our toil in this land.

For, as soon as we shift the “conflict” from one between us and the Arab states to one between us and the fictitious Palestinian nation, the war between us and the Arabs will actually become a war of returning a homeland to a conquered people. The basic proportions of this war will not only not shrink, they will expand, and every advocate of justice will hurriedly go to help the victim. And if this is the case with the “New Left,”8 it is all the more so with the Arab states, beholden as they are to the Palestinian people.

So as to avoid a basic mistake, incidentally, I would like to stress, not for reasons of political expediency or ideological convenience, that we should insist on laying bare the fiction of the Palestinians as a people with a distinctive ethnic, political, and national character. If this distinctive character had existed, we would not have denied it lest we base Israel’s struggle on a falsehood.

But for the same reason, I think that we must not assume that this fictitious Palestinian people will undermine the rationale for the Jewish existence here and the fundamental meaning of the Return to Zion,9 from its inception to this day.

Things have reached the point that the quixotic among us nowadays claim that Zionism’s prophets ignored the problem of the Palestinian Arab people’s existence, either out of short-sightedness or simple ignorance.

But the truth is otherwise. The truth is that Zionism’s prophets saw the reality, the actual reality, not the counterfeit and fabricated supposed reality seen today both by our enemies and by ourselves. They saw a sparse settlement of Arabs, with no distinctive ethnic and political character, in a land with borders, domains, and political configurations of every conceivable kind.

Insofar as there were any hesitations among the Zionist settlers, the hesitations only concerned the individual Palestinian Arab resident, who was to be compensated and protected, not the whole Palestinian Arab people. Such a people did not exist. Herzl, who said that the object of Zionism was to restore a people without a land to a land without a people,10 was not short-sighted. Rather, he saw the truth and said as much, the triumphant truth that, above all else, made the Return of Zion possible and gave it its historical and practical justification

Yet the very same Palestinian Arab people, not only the supposedly short-sighted Zionists, did not see it either. The truth is that in all the political documents on the region’s history from the beginning of the century until today–not to mention before–we find no Palestinian nation, either by description or by name. Neither the English, nor the French, nor the Russians saw this nation. What’s more, the Arabs themselves did not see it. Nor are the Arabs of one mind about the Palestinians’ existence even today.

Some time ago, while paging through texts, I came across a fact that may have been forgotten. At the December 1944 conference of the British Labor Party, a resolution was adopted urging a policy that would allow the Jews to become a majority in Palestine by increasing immigration and by “encouraging the Arabs to move out as the Jews move in.”11

Under this resolution, the Arabs would receive due compensation for their lands, and their settlement in other Arab countries would be generously organized and financed. The resolution goes on to mention, in justification of its position, that the Arabs have vast territories and that they should not deny to the Jews a territory smaller than Wales. What’s more, the resolution’s authors even recommend looking at whether it would be possible to expand the Jewish territory by “apportioning lands to the Jews by agreement with Egypt, Syria, or Transjordan.” Incidentally, this last recommendation was, in fact, implemented, not “by agreement,” but in the Six-Day War.

It is not important, at the moment, to wonder about the Labour Party’s policy after it came to power. What’s important for our purposes is to note that even as judicious a body as the Labour Party Conference did not see a distinctive Palestinian people. Indeed, it is inconceivable that the authors of the resolution should have disinherited a nation of its land by endorsing its emigration and financing its resettlement in other countries.

Not even Churchill was able to see a Palestinian Arab national collective when he was colonial secretary in 1921, when four-fifths of the territory intended for the Jewish national home became a Transjordanian kingdom and ceased to be called “Palestine.” Nor did the 1937 Peel Commission, which recommended a further division, see any such national collective. Under this proposal, a further eighty percent of the territory remaining from 1921 was to have been annexed to Transjordan and likewise stripped of its special appellation “Palestinian.”

Even the charter of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, quoted by Dr. Harkabi12 in Maariv, states that Palestine is part of the greater Arab homeland and the Palestinian people is part of the Arab nation.13 It further says that the Palestinians will decide on their self-definition after liberation and only then will it be determined if it is a Palestinian or a Jordanian collective.14

Even Professor Jacob Talmon,15 for all his ardor for this Palestinian collective,16 even states in a 1967 letter to Albert Hourani17 that the Arabs themselves vehemently denied, until recently, the existence of a separate entity called “Palestine” and forcefully asserted that the Holy Land is merely Southern Syria.18

The government now talks of the need to launch a campaign to influence public opinion in America. But what’s truly needed is different, and its dimensions extend beyond the exigencies of the hour and even the age. Where the principles of the war and the existence and history of the Jewish people are concerned, our policy throughout these two fateful years has wasted, obscured, and scattered into the wind something that must be corrected–and not only in regard to American public opinion. We owe this to the Jewish people, to their history, to the terrible price this nation paid for being righteous in its conflict with the Arabs. We owe it to the hitherto distorted truth; we owe it to the public face of the Jewish people, whose image has been warped more by the conceptual defeat of our policymakers than by our military victory. We have to prevent the illness in certain intellectual circles of ours from becoming the intellectual illness of the Jewish people. Anyone who talks of correcting the distortion by increasing the hasbara budget and by appointing experts only adds to the farcical character of our intellectual defeat. What needs to be corrected today is nothing less than foundational, and there is no greater and more pressing task than this.

- Fellow poets Chaim Gouri and Uri Zvi Greenberg, among others, also joined the Movement for Greater Israel.

- Although Nixon would later distinguish himself as a friend of Israel, his posture toward the Jewish state for the first two years of his presidency was less sympathetic. This was a departure from the more supportive line of Nixon’s predecessor, Lyndon Johnson. The contrast was illustrated by an episode involving the sale of Phantom jet fighter-bombers to Israel. In one of his last acts as president, LBJ authorized the sale of the aircraft to the Jewish state. While President Nixon had supported the sale while campaigning as a candidate, he reversed himself once in office, declining Israeli requests to buy more aircraft and even holding up shipments of ones purchased during the Johnson administration. Meanwhile, the Soviets plied Egypt with arms, creating an air defense umbrella for Cairo.

- In the interest of clarity, several words were omitted from this rendering. With the omitted words restored, the passage reads as follows, “This opinion has become so deeply rooted within us and so comfortable for us that it seems that in order to augment and justify this convenient opinion, our whole policy–in its formulation and its its delinquencies–has become a kind of healing process, as we recover from the blow of victory and invent remedies for it. So, Let’s deal wisely with it, lest it multiply.’”

- Quotation from Exodus 1:10 meaning “to stop something undesirable from growing.” Said of the Hebrews by the pharaoh.

- Lord Caradon, British delegate to the U.N. in 1967 and one of the drafters of UN Resolution 242, described the motion’s proposal of land for peace as a “package deal.”

- Abba Eban, foreign minister from 1966 to 1974

- Radical faction of the left that emerged in the 1960s and, in the latter half of the decade, took up the Palestinian cause. The progressive movement of today descends from the New Left.

- Whereas here Alterman contends that the “fictitious” existence of a “Palestinian people” does not, in itself, do the Zionist case any harm, earlier he asserts that a “separate Palestinian…entity…would strike at the roots of our whole existence and all our toil in this land.” Perhaps the distinction he is making, which would indeed resolve this apparent contradiction, is that merely affirming the existence of a Palestinian people does not, in itself, undermine the Jewish right to the country or the legitimacy of Zionism, but creating “a separate Palestinian…entity” would do just that. In other words, a false claim merely asserted, not converted into a political reality, does Zionism no harm.

- Several words are omitted. With the omissions restored, the paragraph reads as follows: But for the same reason I think that we must not assume that this fictitious Palestinian people will undermine the foundation of the logic and the justification of the Jewish existence and the fundamental meaning of the Return to Zion from its inception to this day.

- Here Alterman falls into error, as Herzl never used the slogan “land without a people for a people without a land.” The earliest variant of the slogan was coined in the 1840s by the Scottish minister Alexander Keith. Not many years later, the slogan entered into wider if still somewhat limited usage when it appeared in the writings of the British peer Lord Shaftesbury. It wasn’t until the early twentieth century, after it was used by Zionist activist Israel Zangwill, that it became proverbial.

- The relevant portion of the resolution, adopted at the Labour Party’s Forty-Third Annual Conference, reads as follows:

“Here we have halted half way, irresolute between conflicting policies. But there is surely neither hope nor meaning in a ‘Jewish National Home’, unless we are prepared to let Jews, if they wish, enter this tiny land in such numbers as to become a majority. There was a strong case for this before the War. There is an irresistible case now, after the unspeakable atrocities of the cold and calculated German Nazi plan to kill all Jews in Europe. Here, too, in Palestine surely is a case, on human grounds and to promote a stable settlement, for transfer of population. Let the Arabs be encouraged to move out, as the Jews move in. Let them be compensated handsomely for their land and let their settlement elsewhere be carefully organised and generously financed. The Arabs have many wide territories of their own; they must not claim to exclude the Jews from this small area of Palestine, less than the size of Wales. Indeed, we should reexamine also the possibility of extending the present Palestinian boundaries, by agreement with Egypt, Syria, or Trans-Jordan. Moreover, we should seek to win the full sympathy and support both of the American and Russian Governments for the execution of this Palestinian policy.” The online archives of the State Department’s Office of the Historian preserve the excerpted document in full: https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1945Berlinv02/d1345#:~:text=Here%2C%20too%2C%20in%20Palestine%20surely,carefully%20organised%20and%20generously%20financed.

- Yehoshafat Harkabi was an eminent Israeli Arabist who served as the director of AMAN (Israel’s military intelligence agency) from 1955 to 1959.

- Alterman is referring to the first article of the PLO Charter: “Palestine is the homeland of the Arab Palestinian people; it is an indivisible part of the Arab homeland, and the Palestinian people are an integral part of the Arab nation.”

- Alterman is in error. The PLO charter does not address the question of Palestinian self-definition or Palestine’s relationship to Jordan.

- Jacob Talmon was a celebrated Israeli historian and professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem who was awarded the Israel Prize.

- Literally “fire in one’s bones”–a Hebrew expression, inspired by Jeremiah 20:9, meaning “burning desire/passion for.”

- Albert Hourani was an influential British historian of Lebanese origin. An opponent of Zionism, he was enlisted by the Arab Office in London as an occasional spokesman.

- After the First World War, and even into the 1930s, many Palestinian leaders called their homeland “southern Syria” because the Levant (the region encompassing Syria, Lebanon, Jodan, and Israel) is known by one of its Arabic names as “Greater Syria.” These leaders urged the annexation of Palestine to Syria.