Ken Stein, The Arab-Israeli War of 1948 – A Short History of the Israel War of Independence

Ken Stein – The Arab-Israeli War of 1948 – A Short History

Introduction

Otherwise known as Israel’s War of Independence, or, “the nakbah” or disaster to the Arab world because a Jewish state was established, the war was fought between the newly established Jewish state of Israel opposed by Palestinian irregulars, and armies from five Arab states. Official beginning of the war is usually given as May 14, 1948, the date Israel declared itself an independent Jewish state, but the war’s first of four phases began in November 1947. Lasting for two years, the war ended with armistice agreements signed in 1949 between Israel and four Arab states. Brokered by the United Nations, these agreements did not result in the Arab world’s diplomatic recognition of Israel. Instead a ‘technical’ state of war characterized Arab-Israeli relations until 1979, when the Egypt-Israeli Peace Treaty was signed.

For the remainder of the century, the Arab-Israeli war of 1948 had international, regional, and local implications. This was the first of four major Arab-Israeli wars fought over Israel’s legitimacy or geographic size. The war crystallized an already emerging Palestinian Arab national desire to wrest Palestine from Israel’s Zionist founders. After some eighty years of step-by-step building of a Jewish national territory, the State of Israel emerged in the shadows of the holocaust. For the next three decades Israel would devote its resources and energy to preserving its territorial integrity and absorbing Jewish immigrants in peril. Though the United States reluctantly and the Soviet Union supported Israel’s creation, Washington and Moscow parted ways, supporting Israel and the Arab world respectively, adding the Arab-Israeli conflict and the Middle East to their keen global Cold War competition. And for the Arab world, eradicating the results of this “disaster”—Israel’s creation—became the focal point of political attention, ideological coherence, and resource expenditure for subsequent decades. As Egypt’s President Nassar declared about the June 1967 War, it was aimed at Israel’s destruction.

Causes of the War

The war was fought over whether a Jewish state should be established in the geographic areas of its ancient homeland, strategically situated in the middle of the Arab and Muslim world. From 1917 to 1947, the British government-controlled Palestine, securing it for themselves to protect their adjacent interests in Egypt and the Suez Canal as the strategic link to their presence in India. When World War II ended in 1945, the British, who had given Jews and Arabs political autonomy but not independence in Palestine, realized that they could neither contain the Zionist aspirations for a Jewish state nor provide protection for the Arab community’s political rights. In spring 1947, Britain turned the issue of Palestine’s future over to the United Nations. On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly passed a resolution to partition Palestine into Jewish and Arab states. It also called for an international regime for Jerusalem and an economic union between the proposed Arab and Jewish states. France, The United States, and the Soviet Union voted for partition while Britain abstained, and Muslim and Arab states vigorously opposed the partition plan, wanting instead a federal solution, one state in which the Arabs would be the majority.

After the partition vote, Britain promised to evacuate her troops from Palestine by February 1948, but settled eventually on May 14, 1948. In the process of leaving Palestine, Britain did not cooperate closely with the Jewish Agency, the main Jewish political body in Palestine. Instead, it decidedly sided with Arab interests. Since the late 1930s, Britain did not wish to provoke her Arab or Muslim friends and jeopardize access to oil interests. In keeping with a pro-Arab policy, in early 1948, Britain embargoed the import of weapons for Jewish forces and turned over strategic locations to Arab forces in Palestine.

with an international regime for Jerusalem, November 1947

Course of War

Arab political and physical opposition to the creation of a Jewish state was as passionately held as were Zionists committed to see their state established. Both sides made military preparations and skirmished with the other. Arabs and Jews organized multiple militias, with the Jewish fighting groups into one command structure very quickly after the war started.

Phase one of the war lasted from the partition resolution, November 29, 1947 until the British evacuated Palestine on May 14, 1948. During this phase, Jewish forces were on the defensive, Arab forces mustered but were disorganized with few leaders to take charge, as an already fraying Arab community dissolved further. After secret talks with Zionist leaders in 1947 and 1948, which promised him portions of lands that were to be part of the Arab state, Emir Abdullah of Transjordan, driven by a desire to control all of Jerusalem, did not remain out of the hostilities with the nascent Jewish state.

In 1945, the Arab League of States was established. Its primary function was to deny the Jewish state’s establishment in Palestine. In September-October 1947, in response to a genuine offer from Zionist leaders, Arab League representatives refused to reach a peaceful two-state solution, even acknowledging that going to war with the Jews might mean the loss of Palestine altogether. Other Arab leaders began to send troops to Palestine’s borders for a coming war. They formed the Arab Liberation Army for Palestine. Some 10,000 Arab volunteers divided Palestine’s coverage into northern, central, and southern sectors. Rifles, other light weapons, and funds were provided by surrounding Arab states, with groups formed under the direction of Iraqi, Palestinian, and Egyptian heads. These forces had little military training and were fragmented by family, ethnic, ideological and regional loyalties. Throughout all phases of the war, Egyptian and Jordanian leaders and their forces failed to cooperate in military planning, exchange of intelligence information, and operations; the head of the Arab Liberation Army clashed severely with local Palestinian political leaders. Severe Arab disunity and very long lines of supply and communication allowed the geographically isolated and meagerly equipped Jewish forces a chance at success. Out of fear for their families’ security, hundreds of thousands of Arabs in Palestine fled their villages, forced to leave their lands and homes. By the time the 1948 war ended, more than 700,000 Arabs had fled Palestine.

Jewish forces sought to protect outlying Jewish settlements, while Arab forces successfully assaulted various Jewish quarters in cities and rural settlements throughout Palestine. Roads between Jewish settlements were cut, while in Haifa, Acre, and Safed, Jews took control of these and other northern cities. On the other hand, by May 1948, Jews in Jerusalem were virtually isolated from the rest of the country. The Jewish Agency’s planning witnessed the first delivery of additional weapons from eastern Europe. Jews in neighboring states were attacked because they were considered to be sympathetic to Zionist aspirations. By the end of the 1948 war, more than 450,000 Jews from Arab lands would be compelled to leave because of Arab antagonism toward the newly established Jewish state.

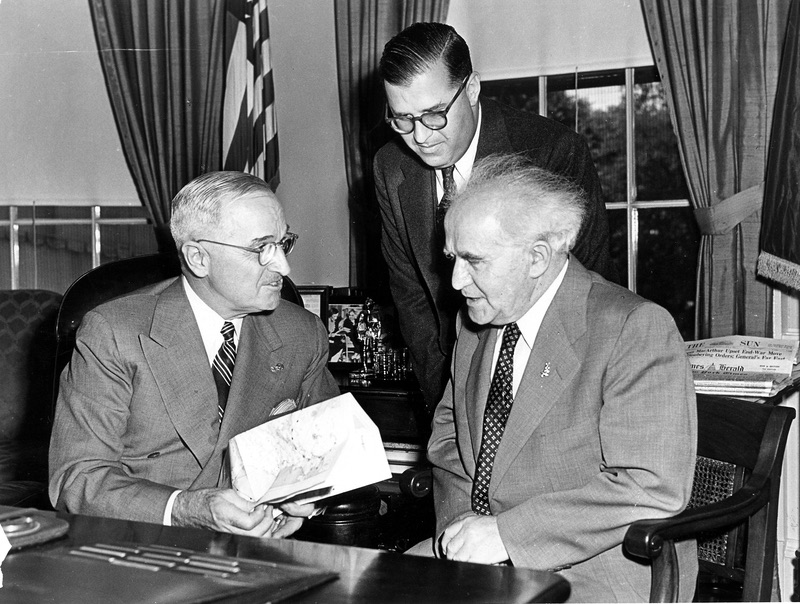

Though threatening to block the transfer of philanthropic funds from Jewish sources in the United States, the State Department failed to persuade the Zionists to postpone declaring statehood. Despite strong opposition from the State Department for the creation of a Jewish state, President Truman recognized Israel officially moments after statehood was declared. As it turned out, Israel extracted almost three-fourths of the $300 million direct costs of the war from its own citizens, and while 86 per cent of Israel’s arms costs was born by foreign sources.

Phase two of the war lasted from Israel’s Declaration of Independence on May 14 to June 11, 1948. When the official war started, Israel mobilized perhaps 30,000 men and women; the Arab states had combined forces in excess of that number. The Arab advantage was in the equipment and air forces at their disposal. However, by the end of May, Israel halted an Egyptian ground attack in the south; by June 9, Israeli forces relieved the Arab siege around Jerusalem. When the first UN Truce was applied two days later, the Syrian army had gained little in the north, the Egyptians had gained a foothold in the Negev desert in the south, and the Transjordanian and Israeli armies were exhausted. From June onwards, the UN tried to mediate and supervise a cease-fire. The UN Mediator, Count Folk Bernadotte, presented his own plan for resolution of the Palestine-Israeli conflict, disregarding both the UN partition plan and the results of the early rounds of fighting. His ideas infuriated Jews because he wanted to virtually negate the establishment of Israel. After resubmitting revised ideas for resolving the conflict, he was killed in Jerusalem in September; his assistant the American Ralph Bunche succeeded him and mediated the armistice agreements signed at the end of the war.

Phase three of the war last from July 8 to July 18, 1948. By then, the US State Department realized that Israel would win the war or at least not go down to a crushing defeat. During the previous truce-period, Israeli and Arab forces used the lull in fighting to rearm and to reorganize. Arab forces increased to a total of 40,000, Israeli forces to 60,000.

Equipment and ammunition were replenished on both sides. Israel obtained oil from Rumania, guns and ammunition from Czechoslovakia and France, and continued political support from Russia. With the acquisition of tanks and artillery, the Israeli side’s improvements were noticeably superior, giving its army a potential offensive punch. During this phase, Israel consolidated its grip on the center and northern areas of Palestine, but still wanted to take the Negev desert in the south.

End of War

When the fourth phase of the war started in October, Israeli forces had climbed to 90,000 men and women, including 5,000 volunteers from abroad. Already in September, Egypt had organized an “All Palestine Government” with its seat in Gaza, clearly an Egyptian puppet regime, but it lasted less than three months. Meanwhile, Jordanian and Egyptian leaders continued to vilify each other. In late December, the United Nations, which had repeatedly called for a cease-fire and truce on all fronts, finally issued a request for a permanent armistice in all parts of Palestine. Significantly, at the end of December 1948, the UN passed a resolution suggesting that refugees wishing to return to their homes and live in peace with their neighbors should be permitted to do so, or receive compensation for property left behind. The largest stumbling blocks in fulfilling this resolution were that Arab leaders did not want to countenance peace with the newly formed Jewish state, and Israeli leadership would not permit the return of refugees until Arab states recognized Israel’s legitimacy.

When this phase of the war ended on January 7, 1949, Israeli forces had made it untenable for Egyptian troops to sustain a presence in the Negev area. On January 12th, on the Island of Rhodes, Egyptian-Israeli armistice talks commenced, but no Arab state negotiated with Israel in face-to-face talks. Arab states did not permit a separate Palestinian delegation to negotiate with the Israelis. Nonetheless, Egyptian-Israeli talks resulted in a signed armistice agreement on February 24, 1949. Similar agreements were signed by Israel with Lebanon on March 23, with Jordan on April 3, and Syria on July 20. Iraq was the only Arab state not to sign an armistice agreement with Israel. No peace treaties were signed that ended the conflict between Israel and Arab states; that first treaty only came with the Egyptian-Israeli Treaty in 1979. No agreement was signed in 1949 between Israel and any Palestinian representatives; the first agreement signed between them was the Oslo Accord in 1993.

Consequences of War

After the war, what happened to the area that the UN proposed for an Arab and Jewish state in November 1947? Israel controlled all of Palestine, with the exception of the Gaza Strip, which was administered by Egypt and the so-called West Bank of the Jordan River, taken during the war and eventually annexed by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in 1950.

The West Bank and Gaza Strip would be taken by Israel in the June 1967 war. From 1949 until the end of the June 1967 War, the old city of Jerusalem and most Jewish Holy Sites fell totally under Jordanian control. No economic union was created. And neither Jordan nor Egypt helped to establish a Palestinian state after the 1948 war in the Palestinian areas under their control, either in the Gaza Strip or West Bank. For Palestinian Arabs, the 1948 Arab-Israeli war became a traumatic benchmark in their history. A majority of them displaced by the war became pariahs and wards of neighboring Arab countries’ policies. Only Palestinians who fled to Jordan were offered citizenship; the UN established a conciliation commission to bring about the recently signed truces; and a United Nations Work Relief Agency was created to assist the Palestinian refugees. Some 150,000 Palestinians remained in the newly established Israeli state and eventually became Israeli citizens. Palestinian refugees solidified their national consciousness living outside Palestine with a firm commitment to destroy Israel and return to their homes of residence before the war. Only in 1964 did they form their own Palestine Liberation Organization and continued the call for Israel’s destruction via armed struggle. For the broader Arab world, Israel’s survival was a terrible stain on contemporary Arab history. The Arab world writ large continued to oppose Israel through war, economic boycott, international political isolation, and armed guerrilla attacks. Both Arab writers and Israel’s Palmach Commander Yigal Allon have given their reasons for why the Zionists won and the Arab sides lost the war.

For Zionists who had diligently labored since the end of the 19th century to establish a territory where Jews could be free from persecution, the war culminated in the reestablishment of a Jewish state. It was heralded as a justified redemption after six million Jews were killed systematically by the Nazi perpetrated Holocaust of World War II. That was only part of the evolving history; the most significant part was that Jews without political or physical power in the 19th century learned over half a century to persevere and improvise in forming a state. Finally, the 1948 Arab-Israeli war solidified world Jewry’s territorial identity in its ancient homeland; it became a sanctuary for other Jews in need and crisis around the world, and a powerful emotional attachment for Jews and non-Jews around the world.

- Derek Penslar, “Rebels Without a Patron State, How Israel Financed the 1948 War,” in Rebecca Kobrin and Adam Teller (eds.), Purchasing Power: The Economics of Modern Jewish History Jewish Culture in Contexts, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015, pp. 186-188, and 191.

- Jon and David Kimche, Both Sides of the Hill Britain and the Palestine War, London: Secker and Warburg, 1960, p. 223.

- Howard M. Sachar, A History of Israel From the Rise of Zionist to Our Time, New York:Alfred Knopf, 1976, p. 339.