Egyptian-Israeli Negotiations, 1977-1981

Ken Stein, October 28, 2024

When Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter became the 39th President of the United States in 1977, he had little foreign policy experience, particularly regarding the Arab-Israeli conflict. Despite this, he prioritized Middle East peace upon taking office. Carter’s approach diverged from his predecessors’ step-by-step diplomacy, favoring a comprehensive solution. Influenced by his National Security Adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and the 1975 Brookings report, Toward Peace in the Middle East, Carter aimed for a structured and complete resolution to the conflict.

Carter’s engineering background inclined him towards comprehensive solutions rather than incremental agreements. He believed rational discussions, free from ideological or historical constraints, would yield more than bilateral agreements. However, he underestimated the readiness of Middle Eastern states to negotiate and recognize each other. Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat was an exception, seeking substantial progress but not willing to be hindered by other Arab states’ reluctance or US procedural delays. According to close adviser, Tahsin Bashir, Sadat by nature was impatient, clever, always seeking policy objectives through multiple pathways. Sadat aimed to restore Israeli-held Sinai to Egyptian sovereignty and was open to Carter’s efforts for a comprehensive resolution, but he prioritized Egypt’s immediate goals. Sadat felt deeply for the Palestinians but he was not willing to postpone accessing from the United States, technological, economic, financial, or military needs for Egypt because the Palestinians were not prepared to accept an end to the conflict with Israel. Likewise, Sadat was not going to wait at all for the Saudis, Syrians, Jordanians or others to reach understandings with Israel. Egypt was first.

Sadat’s secret channels with the Israelis in September 1977, through the Rumanians and Moroccans revealed Israel’s readiness to negotiate over Sinai, leading to his historic November 1977 visit to Israel. This visit aimed to refocus Carter’s administration on substantive issues rather than procedural details. Sadat desired the US to be a ‘full partner’ in the negotiations, supporting withdrawal on all fronts, including the West Bank and Jerusalem. However, Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, whom Carter met in July 1977, was steadfast in his opposition to a Palestinian state and insisted on retaining the West Bank and Jerusalem. This fundamental disagreement set the stage for complex negotiations. Moshe Dayan, Israel’ Foreign Minister informed Carter in September 1977 of Israel’s ‘red lines’ that she would not cross concerning negotiating procedure and substance; “no negotiating format where the US would throw its weight around and push Israel away from steadfastly held positions, including no complete withdrawal from the West Bank, no Palestinian state, and no return to the June 1967 borders.”

The Carter administration faced internal and external pressures, including worries about oil prices and the potential for an embargo that could harm the US economy and Carter’s re-election prospects. The administration’s push for a political resolution for the Palestinians was partly driven by a desire to appease Saudi Arabia. However, the Saudis were not ready to accept even a partial political solution with Israel, a significant miscalculation by the Carter administration.

As a mediator, Washington had to be even-handed, tilting away from a mostly pro-Israel stance. This required challenging Israel’s refusal to engage the PLO, its settlement-building in the territories, and its withdrawal from the territories secured in the June 1967 War. Brzezinski and Carter believed reducing Israel’s political influence on US Middle East policy was in Washington’s national interest. However, this approach underestimated the unwavering support Israel’s American allies had for Israel’s security needs. This miscalculation led to growing anger within the American Jewish community towards Carter’s administration. Carter’ chief political adviser, Hamilton Jordan recognized that pushing Israel into unwanted positions about her security had a domestic cost, but nonetheless the administration remained relentless in putting public pressure on Israel.

In the spring of 1977, Carter publicly called for a Palestinian homeland and indicated the PLO should be involved in negotiations, angering Begin and contributing to tensions in the US-Israel relationship. Begin’s government, formed after his election victory, prioritized Israeli territorial retention over comprehensive peace, particularly concerning the West Bank and Jerusalem. The Joint US-Soviet Statement on the Middle East in October 1977 further strained relations by inviting Soviet involvement in the peace process and addressing the Palestinian question. And Carter still wanted a totally unwilling PLO to participate in negotiations by recognizing Israel’s right to exist. Sadat grew impatient with procedural details that were stagnating discussions; he remained focused on Sinai’s return.

Sadat’s Jerusalem visit in November 1977 was a historic event the otherwise deeply hateful Arab-Israeli conflict. He did what no other Arab leader dared to do: accept Israel as a reality, and when Sadat spoke to them face to face when he addressed the Israeli people from the parliament. Sadat’s bold step greatly complicated Carter’s comprehensive approach by pushing bilateral Egyptian-Israeli negotiations to the forefront. Begin’s offer of Palestinian autonomy was seen as insufficient by Sadat. Despite this, negotiations continued, with American diplomats mediating compromises and identifying areas of overlap.

In February 1978, the Carter administration proposed a controversial military plane sale to Egypt, Israel, and Saudi Arabia, intended as a package deal. This deal, designed to paralyze the Israeli lobby on Capitol Hill, further strained US-Israel relations. Brzezinski criticized Begin’s autonomy plan for the Palestinians as perpetuating Israeli control. Despite these tensions, progress in Egyptian-Israeli negotiations remained bleak, leading to the realization that Carter’s direct engagement was necessary.

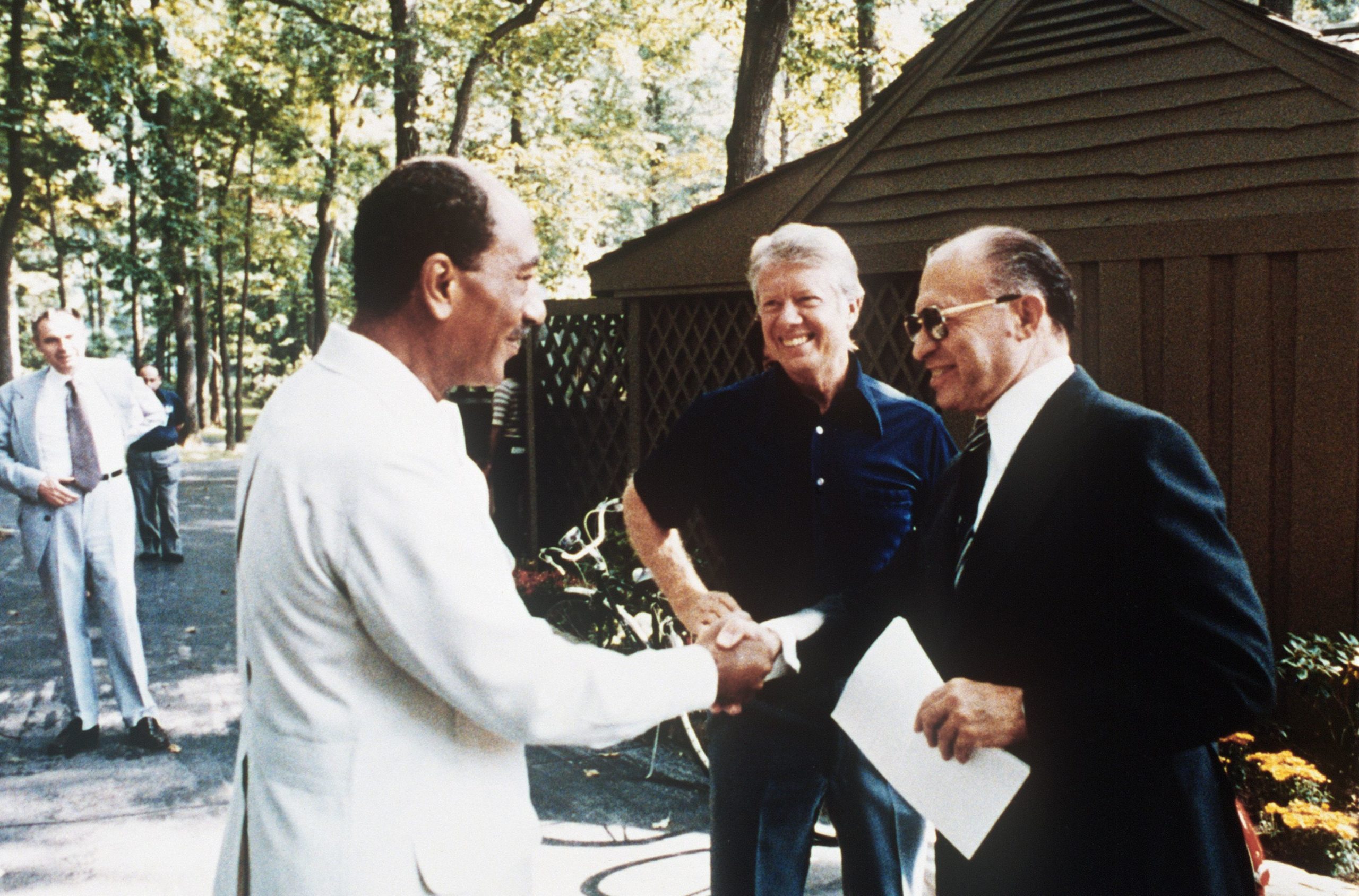

The Camp David negotiations in September 1978 were pivotal. Carter divided the US delegation into professional and political teams, with Secretary of State Cyrus Vance bridging the two. Initial trilateral meetings were unproductive, prompting Carter to meet separately with each side. This allowed him to control the pace and content of discussions, employing compromise language that favored Sadat’s views while pressuring Begin for concessions. Carter had hoped to pressure the Israelis into significant concessions at Camp David but did not succeed. Carter did know before the thirteen days of negotiations began, that Sadat was willing to agree to a bilateral agreement with Israel, but Carter and his team still wanted a comprehensive peace. By September 10, Carter acknowledged to the Israelis that he would not leave Camp David without at least an Egyptian-Israeli agreement over Sinai. This shift in focus allowed the Israelis to make minimal verbal concessions while playing to Sadat’s desire for a substantive outcome from his Jerusalem visit.

Begin’s refusal to evacuate Israeli settlements in Sinai during the talks led to Sadat’s threat to leave Camp Davi, but it is doubtful that he would have done so and sacrificed not having reached a substantive conclusion from his historic public opening with the trip to Jerusalem. Israel’s Aharon Barak, a highly gifted lawyer and later an Israeli supreme court justice suggested to Begin (so he would not have to decide himself) and Begin accepted, that the Knesset decide on the future of Sinai settlements. The Israeli parliament accepted the Accords, including Sinai’s evacuation, in the last week of September 1978.

Unexpectedly, the issue of Jerusalem arose on the final day of negotiations, causing significant tension. Dayan’s confrontation with Carter over Jerusalem nearly derailed the talks. However, side letters appended to the Camp David Accords allowed respective positions to be stated without derailing the agreements. The Camp David draft framework underwent twenty-two versions before final documents were signed, with Carter’s relentless determination and detailed knowledge driving success.

Singularly, the most contentious dispute, and one that would last between them for the rest of their lives arose between Carter and Begin about an Israeli freeze in settlement building at the end of the summit talks. Carter claimed Begin promised a five-year moratorium on building settlements, but the only notes from the meeting that took place on September 16 showed that Begin made no such commitment. This public dispute spilled over into future relations between US Presidents and Israeli Prime Ministers, but the dispute did not halt Egyptian-Israeli treaty negotiations, or their ultimate conclusion. Neither Sadat nor Begin took their eye of the prize of a treaty relationship between the two countries.

The Camp David Accords and the subsequent Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty in March 1979 were crowning foreign policy achievements for Carter, winning Begin and Sadat the Nobel Peace Prize. However, Carter’s popularity boost was temporary. Sadat faced severe backlash from the Arab world for recognizing Israel, while Israel shifted military resources toward its northern border and the West Bank.

The broader outcomes included demonstrating that Arab national interests would override pan-Arabism, affirming that Arab leaders would make peace with Israel while still supporting the Palestinian cause, and highlighting the US’s vital role in successful negotiations. The process also underscored that agreements only succeed when both sides believe they enhance their national interests, with mediators unable to desire an agreement more than the negotiating parties.

Carter’s well intentioned negotiating effort to achieve a comprehensive peace between Israel and her neighbors failed. His achievement and that of talented members of the State Department who served with him, in pushing Begin and Sadat to agree to a Treaty was transformational for Israel and Egypt. At the time however, Arab states and the PLO, were not prepared to accept Israel as a state. And Israel was not prepared to negotiate with the PLO or engage in any diplomacy that would ultimately devolve into a Palestinian state. Like the agreements negotiated during the Nixon and Ford administrations between Israel, Egypt and Syria, the agreements stewarded by Carter were transactions about land and rights, the agreements did not aim at transforming Arab attitudes toward Israel, in part because Arab states were not yet prepared to accept Israel as a reality. In 1993, 1994 and 2020, the PLO, Jordan, and four other Arab states recognized Israel prompted primarily on improving their respective national interests, and the very important reality that the United provided financial, military, and diplomatic incentives to conclude agreements and that insured their longevity.

Just as Begin and Sadat were in part driven to one another because they did not trust Moscow, similarly, the Gulf state countries that aligned with Israel and the US in 2020 and afterwards were significantly motivated by common physical and ideological anxieties emanating from Iran’s Islamic Republic. When the Carter administration left office it left at least two major legacies in the Middle East: a peace treaty between Egypt and Israel, an unprecedented change in Arab state relations with Israel, and a theocratically restructured Iran that relentlessly became for the United States and Israel, their bitterest of enemies in the last half century. The Carter legacies now undergird, along with other key variables (oil, great power involvement, demography, etc.) virtually all aspects of Middle Eastern domestic and inter-regional politics.

Ken Stein, October 28, 2024