June 1977

Source: June 1977, Jimmy Carter Presidential Library, Atlanta, Georgia; Foreign Relations of the United States, Vol. VIII, January 1977-June 1977, pp. 279-295.

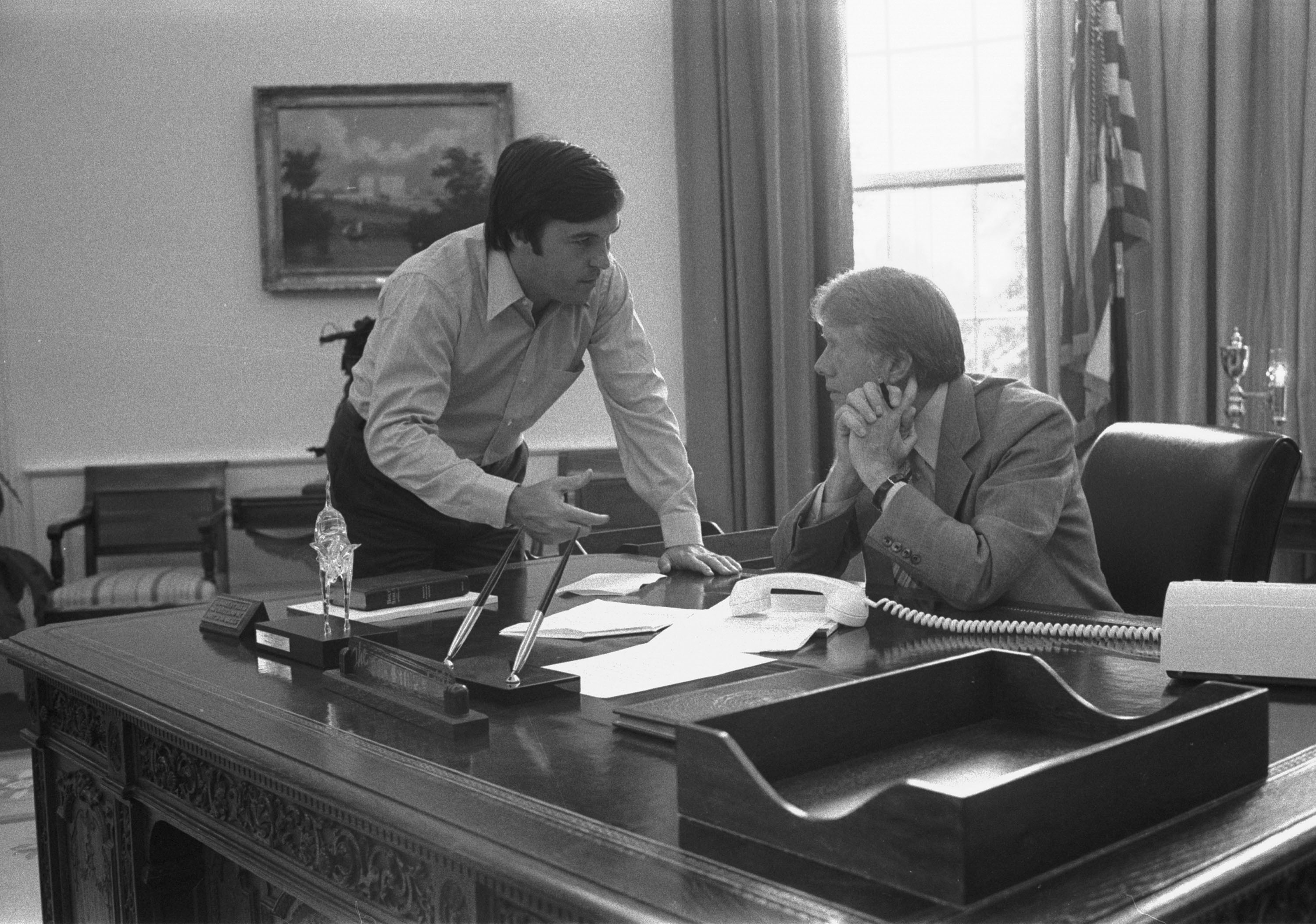

Hamilton Jordan, President Jimmy Carter’s chief political strategist, said in June 1977, “I think it is accurate to say that the American Jewish community is extremely nervous at present. And although their fears and concerns about you (Jimmy Carter) and your attitude toward Israel might be unjustified, they do exist. In the absence of immediate action on our part, I fear that these tentative feelings in the Jewish community about you (as relates to Israel) might solidify, leaving us in an adversary posture with the American Jewish community.”

He continued, “It would be a great mistake to spend most of our time and energies persuading the Israelis to accept a certain plan for peace and neglect a similar effort with the American Jewish community since lack of support for such a plan from the American Jewish community could undermine our efforts with the Israelis. Our efforts to consult and communicate must be directed in tandem at the Israeli government and the American Jewish community. I would advocate that we begin immediately with an extensive consultation program with the American Jewish community.”

Sensitive to the impact of the president’s popularity, Jordan reacted to declining American Jewish public support for the administration’s relentless effort to tell Israel what to do in shaping its foreign and security policies. Led by Carter’s National Security Adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, the administration’s additional objective was to limit American Jewish influence in shaping Middle East foreign policy. Jordan sought to arrest the decline but he ultimately failed to do so because during its four years in office, the administration did not take its foot off the accelerator in pushing and badgering Israel in public, especially with regard to Israel’s refusal to accept the administration’s intentions to have the West Bank become a Palestinian entity.

The more Carter pressed on Israel to negotiate with the PLO and suggest that his administration would pressure Israel into virtually full withdrawal from the territories, the more displeased American Jewish and non-Jewish supporters of Israel and US senators became with his administration. Already from the presidential campaign, many American Jews were skeptical of Carter’s commitment to Israel’s security and Carter was skeptical of American Jewish support for him. According to his biographer, Peter Bourne, in the campaign “no matter what he said or did, [the Jewish community] remained a hurdle he seemed unable to overcome.” In the first six months of the administration, many of the Jewish community’s apprehensions proved accurate about Carter’s effort to pressure Israel and configure its political choices into a mold that his administration sought.

Jordan’s blunt suggestion to have the administration proactively stop its negative remarks on Israel, at least in public did slow down; it continued in private for the rest of 1977 and picked up noticeably in early 1978 when the administration successfully persuaded the Senate to authorize the sale of advance fighter aircraft to Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel. This so-called “Package Deal,” dismayed American supporters of Israel, particularly in the Jewish community and generated worry if not fear among Israeli leaders that the Carter administration was translating its anger against Israel’s reluctance to withdraw from the West Bank and stop settlement building, into active punishment that was potentially threatening to Israeli security needs by lessening Israel’s military advantage over its potential Arab adversaries. Israeli leaders and American Jews were deeply worried that the Carter administration was taking the unprecedented position of stepping away from support of Israel’s security needs.

Throughout the administration’s shepherding of Egyptian-Israeli negotiations in 1978 and 1979, tension in the relationship did not diminish. The Carter administration endorsed four U.N. Security Council resolutions that criticized Israel’s presence in the territories obtained in the June 1967 war. The flight of American Jewish voters from supporting Carter showed up vividly in the Democratic Party presidential primaries in Spring 1980, when many voted for Ted Kennedy who was challenging an incumbent president; it was reaffirmed in the 1980 November general election, one of several factors causing Carter’s election defeat. In that election, Carter received the fewest number of Jewish votes cast for any Democratic presidential candidate in the 20th century.

Carter Administration Reasoning and Method for Seeking the Conflict’s Resolution

By the time the Carter administration took office in January 1977, its foreign policy triumvirate unanimously agreed to exert maximum efforts to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict. Carter, Secretary of State Vance, and National Security Adviser Brzezinski made the calculated and strategic decision to find a comprehensive peace to the three-decade old conflict. It chose to abandon Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s step-by-step approach of securing a series of separate, bilateral Egyptian-Israeli and Syrian-Israeli agreements after the 1973 October war.

Four motivations sparked the Carter administration’s objective to seek a comprehensive resolution to the conflict. First, Carter was powerfully persuaded by Brzezinski that dove-tailed nicely with Carter’s views of civil rights, that the Palestinians needed to have a homeland/entity/state of their own. Second, securing Palestinian self-determination was to be achieved. Additionally, Brzezinski believed and convinced Carter that the Saudi government wanted Palestinian political rights satisfied and that if the Saudis could be appeased or receive from the US progress on the Palestinian issue, then Saudi Arabia would neither raise prices nor impose or threaten another oil embargo on the American economy, as it had done after the October 1973 War. Third, the administration, again with Brzezinski’s lead sought to increase American military and political support for Egypt and Saudi Arabia. This would be done while simultaneously limiting American military assistance for Israel but carefully without abandoning a core US commitment to ensure Israel’s ability to defend itself with security needs. Brzezinski, in seeking an even-handed approach to all American allies in the Middle East, intentionally, he was seeking to remove Israel from its special perch as Washington’s most favored ally in the Middle East. He wanted to put American support other Arab states, especially Saudi Arabia on par with Israel. Embracing Egypt at the same time, already committed to disconnect from Moscow made enormous strategic sense as well.

And fourth and most significantly, according to the administration’s liaison to the Jewish community at the time, Mark A. Siegel, who resigned from the administration because of its increasing anti-Israeli tilt and who spoke with me in an interview in 2010, Brzezinski sought to limit American Jewish influence in the making of U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East. “Brzezinski’s biased views on Israel were manifest. I think Carter was educated by someone … who thought that Israel was a future liability.”

According to Brzezinski’s memoirs, Power and Principle, he told Carter at the outset of the administration that time was of the essence for pushing for a Middle East negotiation, that in the first year of his administration he would have the “maximum” leverage over Israel, and that the leverage would decline as the 1978 congressional elections approached. Moving along this time frame was endorsed by Carter’s core advisers, Jody Powell, Hamilton Jordan, Secretary of State Cy Vance and Vice President Walter Mondale. Brzezinski generated this “sense of urgency” to convene a proposed Middle East peace conference by September 1977 and in effect reduce the influence of Israel in shaping foreign policy as soon as could be possible. In Brzezinski’s view, a conference would take maximum political prerogative out of Israel’s hands.

Brzezinski took a staunch view against Israel and pressed Carter on doing so. Brzezinski made it clear to Carter before Yitzhak Rabin’s visit to the White House in March 1977 that the “Arabs would not accept substantial changes in sovereignty beyond the 1967 lines,” and while Israel might feel vulnerable, “mutually acceptable frontiers reinforced by special security lines or zones designed to enhance Israeli security was possible.” Brzezinski also wanted to press the Arabs to be more forthcoming in their concept of peace and emphasized that the U.S. wanted them to produce an acceptable formula for Palestinian representation.

For Carter, and in this instance more so with Brzezinski, there was a compatibility to push these substantive positions, push the conflict toward some resolution. It is vital to note that Brzezinski possessed a dislike that developed into a disdain for American Jewish involvement in foreign policy making, particularly where Israel’s positions were defended in public. He believed that the president and the national security adviser should own exclusive prerogative over foreign policy, with the secretary of state playing a participatory role. Brzezinski detested the willingness of a majority of senators and representatives to align with Israel on virtually all matters pertaining to Israeli security.

However logical the administration’s objective appeared on paper, it did not fathom Middle Eastern political realities. For the administration, the aggregation of its naivete was particularly conspicuous, especially because it had a team of highly experienced State Department bureaucrats (Harold Saunders and Roy Atherton) who had worked successfully and with great sensitivity for decades during the Johnson, Nixon and Ford presidencies. Certainly, these individuals knew politics and politicians in the Middle East; the only explanation for possible disregard of their experience or suggestions is that what they may have offered to the key decision-makers, Carter, Brzezinski and Vance, was not heard or was dismissed. On this point, Carter domestic affairs adviser Stuart Eizenstat, who had worked intimately with Carter when he was governor and in the 1976 presidential campaign, said: “I sensed that Brzezinski, Vance and to a degree Carter himself saw domestic outreach as a nuisance and felt that foreign policy in general, and the Middle East in particular, should be insulated from domestic politics. Major decisions were made without anyone even informing Ham [Jordan]. And the president’s lack of political sensitivity was sometimes breathtaking. What Carter and Brzezinski did not fully understand was that support for any incumbent Israel government was the ultimate litmus test of Jewish identity for mainstream Jewish leaders.”

In addition to being insensitive to the connection of foreign policy with domestic political implications, the three of them walled themselves off from criticism, at least on matters relating to Israel and the Middle East. Moreover, Brzezinski, Carter and Vance were impatient, calibrating time according to the clock and not the calendar as Kissinger had done. They failed to grasp the profound nationalism of each Middle Eastern leader and their thorough mistrust of one another. The hubris of the administration was remarkable. It did not accept that Israel, the PLO and most Arab states remained unalterably opposed to mutual recognition, let alone convening a Middle East peace conference and trying to solve the conflict in a comprehensive manner. It did not realize how much Israel and the PLO detested each other; it actually believed that Yasser Arafat’s PLO would recognize U.N. Security Council Resolution 242. It did not realize or was unwilling to accept how opposed Israeli politicians were to the idea of relinquishing the West Bank or any portion of it for any interim, partial or long-term agreement that might jeopardize Israeli security, let alone countenance the establishment of a Palestinian state. Making a political arrangement with Jordan, as the Labor Party had contemplated — the Jordan Option — was possible but did not include giving up Israeli security control in or over the West Bank.

When Carter announced in March 1977 his support for a Palestinian homeland with the West Bank in mind, he did not fathom the negative impact any political change in the West Bank would have upon Jordanian national interests or security. He failed to comprehend that Egypt’s Sadat was not going to participate in any negotiations where Egypt would be limited by other Arab participants. Astonishingly, he did not realize how opposed some of those countries might be to any participation by the Soviet Union in any form of Arab-Israeli negotiations.

Carter explained to me in a 1991 interview how the negotiating process would unfold: “There was one process, reconvening a Geneva Middle East conference; I envisioned myself or Cy Vance presiding over it; we never got past the substance [of Israeli withdrawal] down to the details of the process, which we presumed we could do as we prepared for a conference.”

“Ready, shoot, aim” is an accurate way of describing the process that the administration vigorously embraced and wished to implement quickly.

The Objective: Pressure Israel to Withdrawal From Territories

For the Carter administration’s plan to have any chance of working, Israel’s pliant or willing participation was critically necessary. Thus, unlike any previous American administration, from its very outset the Carter team relentlessly engaged in a tug of wills and purposes with Israel, its leaders and Israel’s American Jewish supporters. It did so with Yitzhak Rabin and Menachem Begin leading Israel and sustained it relentlessly through the Camp David and Egyptian-Israeli treaty negotiations in 1978 and 1979 and until Carter lost his bid for a second term to Ronald Reagan in November 1980. For perspective, Carter continued his campaign against Israel and the issue of the territories’ future throughout the four decades of his post-presidency.

What is astonishing is that Carter understood Hamilton Jordan’s warning about the alienation of the Jewish community but chose not to change course. In May 1977, a month before Jordan wrote this memorandum to the president, Carter told Syrian President Hafez al-Assad in Geneva that it was important for the PLO to accept Resolution 242 because “the Israeli position and that of many influential American Jews is that the PLO is still committed to the destruction of Israel.” Carter added, “I need to have American Jewish leaders trust me before we can make progress.”

Later in June, Carter said privately that he had to repair his damaged political base among Israel’s friends and in the process build further support for the peace effort. What is evident is that when he took office, Carter did not know or did not believe that the PLO’s main objective remained Israel’s destruction. I would learn personally when I worked for him in the early 1980s at the Carter Center and at Emory that Carter lacked knowledge about Palestinian politics or Arafat’s hold over it.

What were the administration’s actions and statements that created consternation about Carter among Israelis and American Jewish supporters of Israel? What specifically prompted Jordan to write his memorandum to Carter? In December 1976, Gerald Ford as he was leaving office promised to provide Israel with CBUs, concussion bombs to clear minefields and attack surface-to-air missile sites and underground bunkers that housed enemy airplanes. On February 17, 1977, the Carter administration cancelled the sale. In early March, the administration refused to allow Israel to sell Israeli-made Kfir fighter-bombers to Ecuador because the plane contained an American-made engine. The deal would have brough Israel $150 million in revenue. Part of denying Israel the plane sale was a policy Carter adopted upon coming to office to limit arms sales abroad. And yet at the same time the administration approved the sale of Hawk and Maverick missiles to Saudi Arabia.

In February 1977, Defense Secretary Harold Brown announced that Israeli drilling of oil in Sinai was illegal. In early March, Rabin visited the White House, and Carter made it clear to the media that the visit was a bust. Carter wrote in his memoir Keeping Faith that Rabin “did not unbend at all, nor did he respond. It seems to me that the Israelis, at least Rabin, don’t trust our government or any of their neighbors. I guess there’s some justification for this distrust. I’ve never met any of the Arab leaders but am looking forward to seeing if they are more flexible than Rabin.”

In my interview with Carter in February 1991, he described Rabin as “an unpleasant surprise. It was like talking to a dead fish.”

On March 9, with Rabin still in the United States, the administration announced (without consulting with the Israelis) that in any peace settlement Israel “would have to withdraw from almost all the land it took in the 1967 war, with perhaps minor border adjustments.” On March 17, Carter announced that a “homeland for the Palestinians would be needed” in addition to Israel being recognized, along with secure and recognized borders. In May 1977, Begin was elected Israeli prime minister, and he took office just about the time that Jordan submitted his memorandum to Carter. Well before Begin’s election, the Carter administration’s relationship with Israel was as tense and fractious as perhaps at any time since President Dwight Eisenhower demanded that Israel withdraw from Sinai after the October 1956 Suez war.

By June 1977, Jordan had heard and seen enough in terms of how foreign policy was damaging domestic support. The administration had to stop the bleeding of support from the American Jewish community. Jordan responded by shaping this secret memorandum to Carter. It was so confidential that he typed it himself, gave one copy to Carter and put the second one in his office desk. Jordan was seeking Carter’s help. Jordan was fully aware that American Jewish support for Carter had been critical to his 1976 election. Carter had received 70% of the American Jewish vote. Carter’s pollster, Pat Cadell, had told a key member of Carter’s campaign staff, “If Jews had voted like other white voters in the election, Carter would have lost 109 electoral votes to Gerald Ford.” Included in his review of American Jewish participation in politics was their high percentage in voter turnout, their disproportionate presence in states with large electoral votes, and the vast sums Jews had donated to the previous campaigns of Scoop Jackson, Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey. Jewish contributors accounted for 60% of the large donations made to Carter’s 1976 campaign, and, as Jordan said, “in spite of the fact that you were a long shot and came out of the country where there was a smaller Jewish community, approximately 35% of our primary funds were from Jewish supporters.”

With great candor, Jordan told Carter that his influence with supporters of Israel was in a terrible state of affairs. Jordan’s action-oriented memorandum was designed to slow down the crescendo of building anger from American Jews and from Israel’s congressional friends for the deterioration of the administration’s relationship with Israel. Jordan wrote, “the confluence of foreign policy initiatives” requires “a comprehensive and well-coordinated domestic political strategy for understanding and support of the American people and the Congress.” Jordan wanted to emphasize to Carter that he was not paying enough attention to the impact that foreign policy decisions had on domestic attitudes toward his administration.

Jordan suggested that each high member of the administration meet with leading senators to assuage their negative attitudes toward the Carter administration. Jordan’s memorandum is summarized here, and the full memorandum appears below:

“There is a limited public understanding of most foreign policy issues. Congressional support in some form is needed to accomplish most of your foreign policy objectives. We have very little control over the schedule and timeframe in which most of these foreign policy issues will be resolved. Early consultation with Congress and interested/affected constituent groups is critical to the political success of these policies. Public understanding of most of these issues is very limited. To the extent these issues are understood and/or perceived by the public, they are viewed in very simplistic terms.”

Then Jordan’s memorandum focused on the Middle East and active Jewish participation in the political process.

1. Of all measurable subgroups in the voting population, Jews vote in greater proportion to their actual numbers than any other group. In the recent presidential election, for example, American Jews — who comprise less than 3% of the population — cast almost 5% of the total vote.

2. Of all subgroups in the voting population, Jews register and vote in larger numbers than any other group. Voter turnout among Jewish voters measures close to 90% in most elections.

3. Jewish voters are predominantly Democratic. Heavy support for the Democratic• Party and its candidates was founded in the immigrant tradition of the second and third generation of American Jews and reinforced by the policies and programs of Wilson and Roosevelt. Harry Truman’s role in the establishment of Israel cemented this party identification.

4. As Jewish voters are predominantly Democratic and turn out in large numbers, their influence in primaries is often decisive. In New York state, Jews comprise 12% of the population but traditionally cast about 28% of the votes in Democratic statewide primaries. In New York City, the Jewish population is 20%, but Jews cast about 55% of the votes in the citywide Democratic primaries.

5. The variance in turnout between Jewish voters and other important subgroups in the voting population is staggering and serves to inflate the importance of the Jewish voter. Again, New York state is the best case in point. In New York, Jews and blacks make up about the same percentage of the state’s population. Whereas the turnout in the black community was 35% in the recent presidential election, the turnout in the Jewish community was over 85%. This means that about 500,000 blacks voted in this election and about 1,200,000 Jews voted. You received 94% of the black vote and 75% of the Jewish vote. This means that for every black vote you received in the election, you received almost two Jewish votes.

6. Nowhere in American politics is Jewish participation more obvious and disproportionate than in financial support for political candidates and political parties. But it is a mistake to take note of Jewish contributions to political campaigns without seeing this in the larger context of the Jewish tradition of using one’s material wealth for the benefit of others.

The amount of money the American Jewish community contributes to political campaigns is slight when compared to the monies contributed to favorite charities. In 1976, the American Red Cross raised approximately $200 million. In that same year, Jewish charities raised $3.6 billion. In the two-week period following the Yom Kippur War in 1973, the American Jewish community raised over one billion dollars.

7. In 1976, over 60% of the large donors to the Democratic Party were Jewish.

— Over 60% of the monies raised by Nixon in 1972 was from Jewish contributors.

— Over 75% of the monies raised in Humphrey’s 1968 campaign was from Jewish contributors.

— Over 90% of the monies raised by Scoop Jackson in the Democratic primaries was from Jewish contributors.

— In spite of the fact that you were a long shot and came from an area of the country where there is a smaller Jewish community, approximately 35% of our primary funds were from Jewish supporters.

Wherever there is major political fundraising in this country, you will find American Jews playing a significant role. As a result, Bob Dole is particularly sensitive to the tiny Jewish community in Kansas because it is not so small in terms of his campaign contributions.

8. The Jewish Lobby

Having previously discussed and established the great influence that American Jews have on the political processes of our country, it is equally important to understand the mechanism through which much of this influence is wielded.

When people talk about the “Jewish lobby” as relates to Israel, they are referring to American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). AIPAC is an aggregate of leaders from 32 separate organizations which was formed in 1956 in response to John Foster Dulles’ complaint that he did not know which of the many Jewish groups to deal with.

The leaders from member organizations of AIPAC, although active on behalf of their own organizations on domestic issues, have ceded to AIPAC overall responsibility for representing their collective interests on foreign policy (Israel) to the Congress.

It is important to understand that AIPAC has one continuing priority — the welfare of the state of Israel as perceived by the American Jewish community. AIPAC has wisely resisted efforts to broaden their scope and has continually concentrated on the issues that relate to Israel.

Qualitatively, the principal contacts are articulate, bright and well informed on issues related to Israel. They do not have to be briefed, and many have visited Israel and speak with firsthand knowledge of the issues they are lobbying on. The organizations and people represented by the AIPAC umbrella are the most motivated and skilled primary contact group in the country. They have good relations with other important political constituencies (labor groups, civil rights organizations, etc.) and will not hesitate to use the pulpit to generate support for those issues perceived as being critical to Israel.

The cumulative impact of the Jewish lobby is even greater when one considers the fact that their political objectives are pursued in a vacuum. There does not exist in this country a political counterforce that opposes the specific goals of the Jewish lobby. Some would argue that even the potential for such a counterforce does not exist. It is even questionable whether a major shift in American public opinion on the issue of Israel would be sufficient to effectively counter the political clout of AIPAC.

Credit to Carter’s perseverance and success in stewarding Egyptian and Israeli leaders to bilateral agreements was a high-water mark of his presidency, if not the highest foreign policy achievement of his administration. At the same time, he cultivated a new relationship with Americans and Congress that sought to diminish Israel’s influence in American foreign policy making. He did not fully succeed, but he certainly influenced the willingness of future presidents to disagree openly and often with Israel on a variety of policy matters, most specifically Israel’s management of the territories, its relationship with the Palestinians, and repeated disagreements between U.S. presidents and Israeli leaders on how and where Israel should define its security needs on and beyond Israel’s borders.

— Ken Stein, October 2, 2022

Hamilton Jordan Memorandum to President Jimmy Carter, “Foreign Policy and Domestic Politics: The Role of the American Jewish Community in the Middle East,” June 1977, Jimmy Carter Presidential Library, Atlanta, Georgia

TO: PRESIDENT CARTER

FROM: HAMILTON JORDAN

I have attempted in this memorandum to measure the domestic political implications of your foreign policy and outline a comprehensive approach for winning public and Congressional support for specific foreign policy initiatives.

As this is highly sensitive subject matter, I typed this memorandum myself and the one other copy is in my office safe.

- Foreign Policy and Domestic Politics: The Role of the American Jewish Community in the Middle East

Politics and Foreign Policy

Review of Foreign Policy Initiatives

The Need for a Political Plan

- Consultation with Congress on Foreign Policy Initiatives

- The Role of the American Jewish Community in the Middle East

– Introduction

– Voting History

– Political Contributions

– The Jewish Lobby

– The Present Situation with the Jewish Community

– Taking the Initiative with the American Jewish Community

– Appendix

Summary of Recommendations

Review of Foreign Policy Initiatives

Because you have chosen to be active in many areas of foreign policy during your first year in office, there will evolve soon several critical decisions that will have to be made. And each of these decisions will be difficult politically and will have domestic implications that will require the support and understanding of the American people and the Congress.

The most significant of these decisions relate to specific countries and/or areas of the world. As best I can determine, those decisions which will require action on our part and/or the political support of the people and Congress are:

-The Middle East

-SALT II

-AFRICA

-Normalization of relations with Cuba and Vietnam

-Treaty with Panama

-Withdrawal of troops from Korea

It is my own contention that this confluence of foreign policy initiatives and decisions will require a comprehensive and well-coordinated domestic political strategy if our policies are to gain the understanding and support of the American people and the Congress.

It is important that we understand the political dimensions of the challenges we face on these specific issues:

1. There is a limited public understanding of most foreign policy issues. This is certainly the case with SALT II and the Middle East. This is not altogether bad as it provides us an opportunity to present these issues to the public in an politically advantageous way. At the same time, most of these issues assume a simplistic political coloration. If you favor normalization of relations with Cuba or Vietnam, you are a “liberal”; if you oppose normalization with these same countries, you are “conservative”.

2. To the extent that the issues we are dealing with have a “liberal” or “conservative” connotation, our position on these particular issues is consistently “liberal”. We must do what we can to present these issues to the public in a non-ideological way and not allow them to undermine your own image as a moderate-conservative.

3. Congressional support in some form is needed to accomplish most of your foreign policy objectives. A modest amount of time invested in Consultation with key members of Congress will go a long way toward winning the support of Congress on many issues. Whereas members of Congress do not mind – and sometimes relish – a confrontation with the President on some local project or matter of obvious direct benefit to their district or state, very few wish to differ publicly with the President on a foreign policy matter.

4. We have very little control over the schedule and time-frame in which most of these foreign policy issues will be resolved. Consequently, a continuing problem and challenge will be to attempt to separate out the key foreign policy issues from domestic programs so the two will not become politically entwined in the Congress. This dictates a continuing focus on the historical bipartisan nature of U.S. foreign policy so the Republican members of Congress will be less tempted to demagogue these issues during the 1978 elections.

5. Conservatives are much better organized than liberals and will generally oppose our foreign policy initiatives. To effectively counter conservative opposition, we will have to take the initiative in providing coordination of our resources and political leadership. Our resources at present are considerable, but they are scattered among a variety of groups and institutions. To the extent our policy goals are being pursued, they are being pursued unilaterally by groups and people and without coordination.

The Need for a Political Plan

The very fact that your administration is active simultaneously in many areas of foreign policy dictates a comprehensive, long-range political strategy for winning the support of the American people and the Congress. To accomplish this goal, I would recommend a three-step process:

I. CONSULTATION. Early consultation with Congress and interested/affected constituent groups is critical to the political success of these policies. In almost every instance, Senate ratification of a treaty and/or military and economic support which requires the support of Congress will be required to accomplish these foreign policy objectives. Consequently, it is important that we invest a small amount of time on a continuing basis in consultation with members of Congress and groups/organizations.

II. PUBLIC EDUCATION. Public understanding of most of these issues is very limited. To the extent these issues are understood and/or perceived by the public, they are viewed in very simplistic terms. This is a mixed blessing. On one hand, it becomes necessary to explain complex issues to the American people. On the other hand, because these issues are not well understood, a tremendous opportunity exists to educate the public to a certain point of view. In the final analysis, I suspect that we could demonstrate a direct correlation between the trust the American people have for their President and the degree to which they are willing to trust that President’s judgment on complex issues of foreign policy.

In terms of public education, we have a tremendous number of resources. They include:

-Fireside chats

-Town meetings

– Speaking opportunities for President, Vice-President, First Family, Cabinet, etc.

-Public service media opportunities

– Groups outside government who support policies

-Democratic National Committee

-Mailing lists

-Etc.

III. POLITICAL PLANNING AND COORDINATION. Once foreign policy goals are established, it is critical that political strategies in support of those goals be developed and implemented. And it is important that the resources available to the Administration – both inside and outside of government – be coordinated and used in a way that is supportive of these objectives.

I have attempted in this memorandum to outline the first step in this process – consultation – as relates to foreign policy generally and the Middle East specifically. Steps II and III – public education and political planning and coordination – are the subject of a separate memorandum.

A. Consultation with the Congress on Foreign Policy Initiatives

With many complex foreign policy issues surfacing soon and the need for some form of Congressional support for these policies, I believe that it is important that we take the initiative in consulting with Congress.

The consultation that has taken place to date has been extremely beneficial, but one of the inherent problems is that the same people (bipartisan leadership, Foreign Relations Committee, etc.) are briefed time and again; and little is done to increase the general understanding of our policies among the general membership of the House and Senate.

I would recommend that we begin a comprehensive consultation program with members of the Senate which will allow you and several other key members of the Administration to meet with individual members of the Senate and review with them our progress and problems on each of the following subjects:

-Middle East

-Africa

-Panama

-Cuba

-SALT II

-Vietnam

This will not only result in an increased understanding of and support for our policies, but it will allow us to identify Congressional support and opposition. With a Panama Canal Treaty imminent, SALT II negotiations ongoing and the Mideast situation fluid because of the recent Israeli elections, I believe that it is important that we begin this process soon.

I have attempted to outline in the following pages the way this consultation could take place. There are five persons in the Administration who are well enough informed and sufficiently involved in these issues that they could contribute to this process. They are:

President

Vice-President

Secretary of State

Secretary of Defense

National Security Adviser

As demonstrated in the following chart, if each of these persons would contribute an hour each week to a luncheon meeting or briefing with two senators, we could complete the entire process in ten weeks.

[Chart omitted]Rationale for Assignments

The assignments made were arbitrary on my part, but basically reflected the following thinking:

President – Assigned key committee chairmen, Southern senators and senators who are up for re-election in 1978 and will be politically concerned and/or affected by foreign policy decisions made in the next eighteen months.

Vice- President – Assigned generally liberal Democrats and Republicans on the assumption that most of these people will support our policies but cannot be taken for granted.

Secretary of State – Assigned key Democrats and Republicans who would be flattered to have the Secretary of State take the initiative to consult with them.

Secretary of Defense – Assigned conservative Democrats and Republicans who are likely to be concerned with the military dimensions of the foreign policy decisions we will make in the next couple of years.

National Security Adviser – Assigned a mix of the above.

There is certainly nothing sacred in these assignments; and I would expect Frank Moore to have ultimate responsibility for matching senators with the appropriate briefers.

Introduction

As we go into the Summer with the prospect of a visit from the new Israeli head of state and the possibility of a new Vance mission to the Middle East, I think that it is important that we appreciate and understand the special and potentially constructive role that the American Jewish community can play in this process.

I would compare our present understanding of the American Jewish lobby (vis-a-vis Israel) to our understanding of the American labor movement four years ago. We are aware of its strength and influence, but don’t understand the basis for that strength nor the way that it is used politically. It is something that was not a part of our Georgia and Southern political experience and consequently not well understood.

I have attempted in the following pages to do several things:

- Outline the reasons and the basis for the influence ofthe American Jewish community in the political life of our country.

- Define and describe the mechanism through which this influence is used.

- Describe – as I understand it – the present mood and situation in the American Jewish community as relates to you and your policies; and

- Define a comprehensive plan for consultation with the American Jewish community with the goal of gaining their understanding and/or support for our efforts to bring peace to the Middle East.

B. The Role of the American Jewish Community in the Middle East

Voting History

To appreciate the direct influence of American Jews on the political processes of our country, it is useful and instructive to review their extraordinary voting habits.

- Of all measurable subgroups in the voting population, Jews vote in. greater proportion to their actual numbers than any other group. In the recent Presidential election, for example, American Jews – who comprise less than 3% of the population – cast almost 5% of the total vote.

- Of all subgroups in the voting population, Jews register and vote in larger numbers than any other group. Voter turnout among Jewish voter’s measures close to 90% in most elections.

- Jewish voters are predominantly Democratic. Heavy support for the Democratic• Party and its candidates was founded in the immigrant tradition of the second and third generation of American Jews and reinforced by the policies and programs Wilson and Roosevelt. Harry Truman’s role in the establishment of Israel cemented this party identification. And despite an occasional deviation, Jewish identification with the Democratic Party has remained intact and generally stable despite economic and educational pressures which have traditionally undermined party identification.

In recent national elections, Jewish voters have given the Democratic candidates the bulk of their vote, ranging from the low received by McGovern (65%)to the high received by Humphrey (90%). You received approximately 75% of the Jewish vote nationwide.

4. As Jewish voters are predominantly Democratic and-turn out in large numbers, their influence in primaries is often decisive. In New York State, Jews comprise 12% of the population but traditionally cast about 28% of the votes in Democratic statewide primaries. In New York City, the Jewish population is 20% but Jews cast about 55% of the votes in the citywide Democratic primaries.

5. The variance in turnout between. Jewish Voters and other important subgroups in the voting population is staggering and serves to inflate the importance of the Jewish voter. Again, New York State is the best case in point. In New York, Jews and blacks comprise about the same percentage of the state’spopulation. Whereas the turnout in the black community was 35% in the recent Presidential election, the turnout in the Jewish community was over 85%. This means that about 500,000 blacks voted in this election and about 1,200,000 Jews voted. You received 94% of the black vote and 75% of the Jewish vote. This means that for every black vote you received in the election, you received almost two Jewish votes.

Political Contributions

Nowhere in American politics is Jewish participation more obvious and disproportionate than in financial support for political candidates and political parties. But it is a mistake to take note of Jewish contributions to political campaigns without seeing this in the larger context of the Jewish tradition of using one’s material wealth for the benefit of others.

The amount of money the American Jewish community contributes to political campaigns is slight when compared to the monies contributed to favorite charities. In 1976, the American Red Cross raised approximately $200 million. In that same year, Jewish charitiesraised $3.6 billion. In the two-week period following the Yom Kippur War in 1973, the American Jewish community raised over one billion dollars.

Whereas disproportionate Jewish voting is only politically significant in areas where Jewish voters are concentrated, Jewish contributions to political campaigns are disproportionate nationally and in almost every area of the country.

Some facts that confirm this premise:

-Out of 125 members of the Democratic National Finance Council, over 70 are Jewish.

-In 1976, over 60% of the large donors to the Democratic Party were Jewish.

-Over 60% of the monies raised by Nixon in 1972 was from Jewish contributors.

-Over 75% of the monies raised in Humphrey’s 1968 campaign was from Jewish contributors.

-Over 90% of the monies raised by Scoop Jackson in the Democratic primaries was from Jewish contributors.

-In spite of the fact that you were a long shot and came from an area of the country where there is a smaller Jewish community, approximately 35% of our primary funds were from Jewish supporters.

Wherever there is major political fundraising in this country, you will find American Jews playing a significant role. As a result, Bob Dole is particularly sensitive to the tiny Jewish community in Kansas because it is not so small in terms of his campaign contributions.

The Jewish Lobby

Having previously discussed and established the great influence that American Jews have on the political processes of our country, it is equally important to understand the mechanism through which much of this influence is wielded.

When people talk about the “Jewish lobby” as relates to Israel, they are referring to American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). AIPAC isan aggregate of leaders from 32 separate organizations which was formed in 1956 in response to John Foster Dulles’ complaint that he did not know which of the many Jewish groups to deal with.

The leaders from member organizations of AIPAC, although active on behalf of their own organizations on domestic issues, have ceded to AIPAC overall responsibility for representing their collective interests on foreign policy (Israel) to the Congress.

It is important to understand that AIPAC has one continuing priority – the welfare of the state of Israel as perceived by the American Jewish community. AIPAC has wisely resisted efforts to broaden their scope and has continually concentrated on the issues that relate to Israel.

Leadership/Organization

AIPAC is headed by Executive Director Morris Amitay and Legislative Director Ken Pollack. As an umbrella organization, AIPAC is composed of leaders from major Jewishgroups in the United States, including:

-American Jewish Congress

-American Mizrachi Women

-American Zionist Federation

-Anti Defamation League

– B’nai B’rith

-B’nai B’rith Women

-B’nai Zion

-Central Conference of American Rabbis

-Hadassah

-Jewish Labor Committee

-Jewish Reconstructionist Foundation

-Jewish War Veterans

-Labor Zionist Alliance

-National Committee for Labor-Israel

-National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods

-National Jewish Community Relations Council

-National Jewish Welfare Board

-North American Jewish Youth Council

-Pioneer Women

-Rabbinical Council of America

-Rabbinical Assembly

-Union of American Hebrew Congregations

-Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations

-United Synagogue of America

-Women’s’ League for Conservative Judaism

-World Zionist Organization

-Zionist Organization of America

-Council of Jewish Federation and Welfare Funds

Although the combined membership of these organizations is only several million, their collective mobilizing ability is unsurpassed in terms of the quality and quantity of political communications that can be triggered on specific issues perceived to be critical to Israel. When AIPAC feels that the interests of Israel might be affected by a legislative or executive action, their target lists are mailgrammed.

Several thousand mailgrams to the leadership of the member organizations can be counted on to generate thousands of telegrams, letters and telephone calls for pivotal Congressman and/or Senators. As vote counts are developed, targeted efforts by AIPAC are accelerated. Key Jewish leaders and/or financial contributors are encouraged to personally visit the wavering legislator.

Qualitatively, the principal contacts are articulate, bright, and well informed on issues related to Israel. They do not have to be briefed, and many have visited Israel and speak with first-hand knowledge of the issues they are lobbying on. The organizations and people represented by the AIPAC umbrella are the most motivated and skilled primary contact group in the country. They have good relations with other important political constituencies (labor groups, civil rights organizations, etc.) and will not hesitate to use the pulpit to generate support for those issues perceived as being critical to Israel.

The cumulative impact of the Jewish lobby is even greater when one considers the fact that their political objectives are pursued in a vacuum. There does not exist in this country a political counterforce that opposes the specific goals of the Jewish lobby. Some would argue that even the potential for such a counterforce does not exist. It is even questionable whether a major shift in American public opinion on the issue of Israel would be sufficient to effectively counter the political clout of AIPAC.

Support for Israel in the Senate

The following is a brief analysis of the support for Israel in the United States Senate. On a given issue where the interests of Israel are clear and directly involved, AIPAC can usually count on 65-75 votes. Their breakdown of support in the Senate follows:

Hard Support/Will Take Initiative

Anderson Bayh

Brooke

Bentsen Case*

Church* Cranston Danforth DeConcini Dole

Eagleton Glenn*

Heinz

Humphrey* Inouye

Jackson Javits * McIntyre Matsunaga Metzenbaum Moynihan Morgan

Packwood Ribicoff Riegle

Sarbanes* Schweiker Stone*

Zorinsky Williams

*Member of Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Sympathetic/Can be Counted On In Showdown

Allen

Baker

Bumpers

Byrd, H.

Byrd, R.

Cannon

Chiles

Curtis

Biden

Chafee

Clark

Culver

Domenici

Durkin

Ford

Gravel

Hart

Haskell

Hathaway

Hayakawa

Huddleston

Johnston

Kennedy

Laxalt

Leahy

Lugar

Magnuson

Mathias

Muskie

Nelson

Nunn

Pearson

Pell

Percy

Proxmire

Randolph

Roth

Sasser

Stafford

Stevens

Talmadge

Tower

Weicker

Questionable/Depends on Issue

Bartlett

Bellmon

Burdick

Eastland

Garn

Coldwater

Griffin

Hansen

Hatch

Helms

Hollings

Long

McClellan

McGovern

Melcher

Metcalf

Schmidt

Scott

Stennis

Sparkman

Thurmond

Wallop

Young

Generally Negative

Abourezk

McClure

Hatfield

Summary

31 Hard Voters

43 Sympathetic/Count On In Showdown

23 Depends on Issue

3 Generally Negative

100

To gain a majority on any issue before the Senate, the Jewish lobby has only to get its “hard” votes and half of the votes of those that are “sympathetic”. This would concede all the votes of those in third category.

The Present Situation with the American Jewish Community

For many years, the American Jewish community has basically reflected the attitudes and goalsof the government of Israel. The American Jewish community has seldom questioned- or had reason to question – the wisdom of the policies advocated by the Israeli government. The tremendous financial and political support provided to Israel by the American Jewish community has been given with “no strings attached.”

One of the potential benefits of the recent Israeli elections is that it has caused many leaders in the American Jewish community to ponder the course the Israeli people have taken and question the wisdom of that policy. As a result, I think there is a good chance that the American Jewish community will be less passive and more inclined to provide the new government advice as well as support.

This new situation provides us with the potential for additional influence with the Israeli government through the American Jewish community, but at present we are in a poor position to take advantage of it.

The American Jewish community is very nervous now for a combination of internal and external reasons. It is important that we understand the reasons for their apprehension.

- The election of a new President whose policies have been developed and presented in a manner different from previous Administrations. It is not so much what you have said as the fact that the things you have said (“defensible borders”, “homeland for the Palestinians”, etc.) have been publicly discussed. The leadership of the American Jewish community has heard these things before, but they were always said privately with ample reassurance provided.

- You are not known personally to most of the -national Jewish leaders. And even those that know you have not worked with you over a long period of time, at the national level on matters of direct interest to Israel. Whereas they know and instinctively trust a Humphrey or a Jackson, you are less well known and more unpredictable.

- The cumulative effect of your statements on the Middle East and the various bilateral meetings with the heads of state has been generally pleasing to the Arabs and displeasing to the Israelis and the American Jewish community. You have discussed publicly things that have only been said before privately to the Israelis with reassurances. Press reports of your meetings with the Arabs were always very positive while your meeting with Rabin was “very cool”. The simple fact that there were four Arab heads of state to meet with – and each meeting was perceived accurately as being positive and constructive – and only one meeting with the Israeli head of state – which was widely reported as being unsuccessful – added to this perception problem.

- The election of Begin has resulted in widespread uncertainty among the Jewish community in this country. The leadership of the American Jewish community has had close personal relationships with the leadership of the Labor Party since the creation of the state of Israel. They do not have the same close relationship with the leaders of the Likud Party and are suddenly dealing with new and unpredictable leadership in both countries.

- With the election of Begin, the American Jewish community sees for the first time the possibility of losing American public support for Israel ifthe new government and its leaders prove to be unreasonable in its positions and attitudes. This would put the American Jewish community in the terrible position of seeing its emotional and political investment in Israel overthe past 30 years rapidly eroded.

Taking the Initiative with the American Jewish Community

I think it is accurate to saythat the American Jewish community is extremely nervous at present. And although their fears and concerns about you and your attitude toward Israel might be unjustified, they do exist. In the absence of immediate action on our part, I fear that these tentative feelings in the Jewish community about you (as relates to Israel) might solidify, leaving us in an adversary posture with the American Jewish community.

East settlement, you would lack the flexibility and credibility you will need to play a constructive role in bringing the Israelis and the Arabs together. I am sure you are familiar with Kissinger’s experience in the Spring of 1975, when the Jewish lobby circulated a letter which had the names of 76 senators which reaffirmed U. S. support for Israel in a way that completely undermined the Ford-Kissinger hope for a new and comprehensive U.S. peace initiative. *

The Washington Post said, “The Senatorial letter makes Kissinger nothing more than an errand boy and assures the Arab states that he is powerless to arrange a deal… Kissinger might as well stay home …Under the terms the Senate has laid down, it could, send one of its pages to handle the negotiations.” From Sheehan in The Arabs, Israelis and Kissinger, “Obviously, the (Senate) letter was a stunning triumph for the (Jewish) lobby, a capital rebuke for Kissinger in Congress. Whatever resentment many congressmen may inwardly entertain about the unrelenting pressures of the lobby, the American system predestines them to yield. Israel possesses a powerful American constituency; the Arabs do not…”

If the American Jewish community openly opposed your approach and policy toward a Middle

It would be a great mistake to spend most of our time and energies persuading the Israelis to accept a certain plan for peace and neglect a similar effort with the American Jewish community since lack of support for such a plan from the American Jewish community could undermine our efforts with the Israelis. Our efforts to consult and communicate must be directed in tandem at the Israeli government and the American Jewish community.

I would advocate that we begin immediately with an extensive consultation program with the American Jewish community. This program would focus on:

The Process – Review of what has taken place to date (bilateral with heads of state) and what is planned for the future (probable Begin visit, possible Vance mission, etc.) Also, a definition of the U.S. role. We should stress that we are not trying to “impose a U.S. settlement” nor attempting any “quick fix solution”. We are being widely criticized in the Jewish press for these things.

The Principles – Review of the key items which are being discussed as the basis for a settlement: 1) the nature of peace; 2) the question of borders and security for Israel; and 3) the Palestinian question.

The Prospects – A vision of what Israel could be if peace were permanent and political stability came to the Middle East. Outline of the U.S. belief that Israel would serve as the model of democratic government in the Middle East and become the center of regional trade and finance.

In addition to reviewing these topics, I believe that the American Jewish community should be encouraged – for the first time – to take an active role in analyzing the obstacles to peace and advising the Israeli government on these matters. Any thoughtful analysis of the situation would lead to the conclusion that concessions on both sides are necessary for peace.

To develop a comprehensive plan for consultation with the American Jewish community, it is first necessary to develop a list of individuals, groups and institutions who should be reached.

They include:

Key members of the U.S. Senate – Senators like Humphrey, Jackson, Ribicoff and Church who have been close to Israel and supported it in the Congress.

Key members of the U.S. House -A comparable group in the House who have been close to Israel.

Jewish members of the House – There are 22 members of the House whoare Jewish (See attached listing).

Senate Foreign Relations Committee – It is important to keep them informed and involved.

House International Affairs Committee – It is important to keep them informed and involved.

The American Jewish Press – The American Jewish Press is a powerful instrument for pro-Israeli statements, news and solicitations. These papers -collectively – provide the main analysis of American policy vis-a-vis Israel to the American Jewish Community.

Leaders of National Jewish Organizations – The lay, political and religious leadership of the Jewish community.

[Chart omitted]Local Leaders from Key Communities – About 80% ofthe American Jews are situated in ten cites and/or areas (See attached listing).

Persons with Close Relationships with Israeli Government Officials – There are a number of persons who have unofficially represented .Israeli interests in our country and have close ties to the leadership of the Israeli government. With the Labor Party out of power, this will change; but it is inevitable that the new government will develop close ties with some of the leadership of the American Jewish community. We should develop relationships with these people.

In the following pages, I have outlined a program that will allow us to take the initiative in dealing with the American Jewish community in a positive manner. Using very little of any one person’s time, we could begin and complete this consultation process in the next eight weeks. This plan is targeted at the groups and individuals previously mentioned.

At the end of the process, I believe that we would have the good faith and trust of the American Jewish community going into the next stage of talks. It is difficult for me to envision a meaningful peace settlement without the support of the American Jewish community.

[Chart Omitted]APPENDIX

AIPAC’s Unofficial Listing of Carter Actions/Statements on Middle East Since Taking Office.

Jewish Membersof the U.S. House

Major Centers of Jewish Populationin the United States

- Denial of CBUs.

- Denial of Kfir sale to Ecuador.

- Approval of HAWK and Maverick Missiles to Saudi Arabia.

- Castigation of Israel over Gulf of Suez oil drilling.

- Carter statement on “minor adjustments” during Rabin visit and retraction of statement on “defensible borders.”

- Carter leaks on nonproductivity of meeting with Rabin.

- Carter remark on “Palestinian homeland” at Clinton Town Meeting.

- Carter greets PLO representative at U.N. reception.

- Vance statement that the U. S. would .make its suggestions on all the core issues of the Middle East and that the difference between suggestions and a U.S. plan was only one of semantics.

- Carter statement that he would “not hesitate…to use the full strength of our country and its persuasive powers to bring those nations to agreement.”

- Carter statement that “borders of Palestine” was a core issue of the conflict.

- Excessive laudation by Carter of Sadat, Hussein, Fahd and particularly Assad.

PPM-12.

- Powell statement on “recognized borders” of a Palestinian homeland.

- May 26th Carter statement on Palestinian homeland and compensation and his suggestion that American Jews and the U. S. Congress moderate Begin.

- Powell clarification of May 26th statement of Carter referring to U.S. support for U.N. General Assembly Resolutions 181 and 194.

- Delay of. Israeli requests for coproduction agreements and advanced weapons, i.e., FLIRs, F-16, Grumman Hydrofoil patrol boats, Gabriel missile Components.

- Denial of KFir sales to the Philippines and Taiwan.

- The paucity of statements by Carter since the March 16th Clinton Town Meeting on defining the nature of peace.

- Private statements by Carter that the Arab leaders all desire peace and that Israel is less forthcoming.

- Administration support for weakening amendments to anti-boycott legislation.

* Given to me by Morris Amitay

Jewish Membership of the U.S. House of Representatives

Tony Bielson, D-Calif.

Dan Glickman, D-Kansas

Ted Weiss, D-NY

Marc Marks, R-Pa.

Elizabeth Holtzman, D-NY

Ed Koch, D-NY

Richard Ottinger, D-NY

Fred Richmond, D-NY

Ben Rosenthal, D-NY

Jim Scheuyer;_D-NY

Stephen Solarz, D-NY

Lester Wolfe, D-NY

Ben Gilman, R-NY

Abner Mikva, D-Ill

Sidney Yates, D-Ill (Dean of Jewish Delegation)

Elliot Levitas, D-Ga.

John Krebs, D-Calif.

Henry Waxman, D-Calif.

Joshua Eilberg, D-Pa.

Willis Gardison, R-Ohio

Gladys Spellman, D-Md.

William Lehman, D-Fla.

[Chart Omitted]Summary of Recommendations

If you agree with the premises stated in this memorandum and the recommendations presented; I would recommend the following actions:

1. A meeting with you, the Vice President, Zbig and Frank Moore to discuss the overall consultation process with the Congress.

_____✓__________I agree.

Lets talk first.

2. A meeting with you, the Vice President, Zbig, Prank Moore, Bob Lipshutz and Stu to discuss the overall consultation process with the American Jewish community.

_______✓________I agree.

Lets talk first.

3. That I undertake a planning process that attempts to: 1) inventory our political resources; 2) develop a specific work plan for each foreign policy initiative that focuses on public education; and 3) develop an informal mechanism for the overall work closely with Zbig on all of this.

_______✓________I agree.

Lets talk first.