Zionist/Jewish Economic Development in Palestine before 1948

Ken Stein, March 12, 2025

The Jewish growth in Mandatory Palestine in the period of the New Yishuv to establish a Jewish territory for a state had significantly developed by 1939. Arab leadership in 1938 acknowledged privately that a Jewish state was already in virtual existence in Palestine, though the year before in Bludan, Syria a pan-Arab Congress of 400 delegates rejected the idea of dividing Palestine into Jewish and Arab entities. They wanted no Jewish territorial presence in Palestine. From multiple British, American, and Hebrew sources, it was argued and statistically shown that there was a demographic, territorial, and economic nucleus for a Jewish state, focusing on economic and industrial development indicators, levels of Jewish capital investment, assessing the impact of Jewish immigration on economic growth, and particularly the outsized contribution of Jewish tax revenue to sustaining the British administration in Palestine. The notion is fully incorrect, that somehow a Jewish state simply parachutted into existence in Palestine after World War II. The evidence shows otherwise.

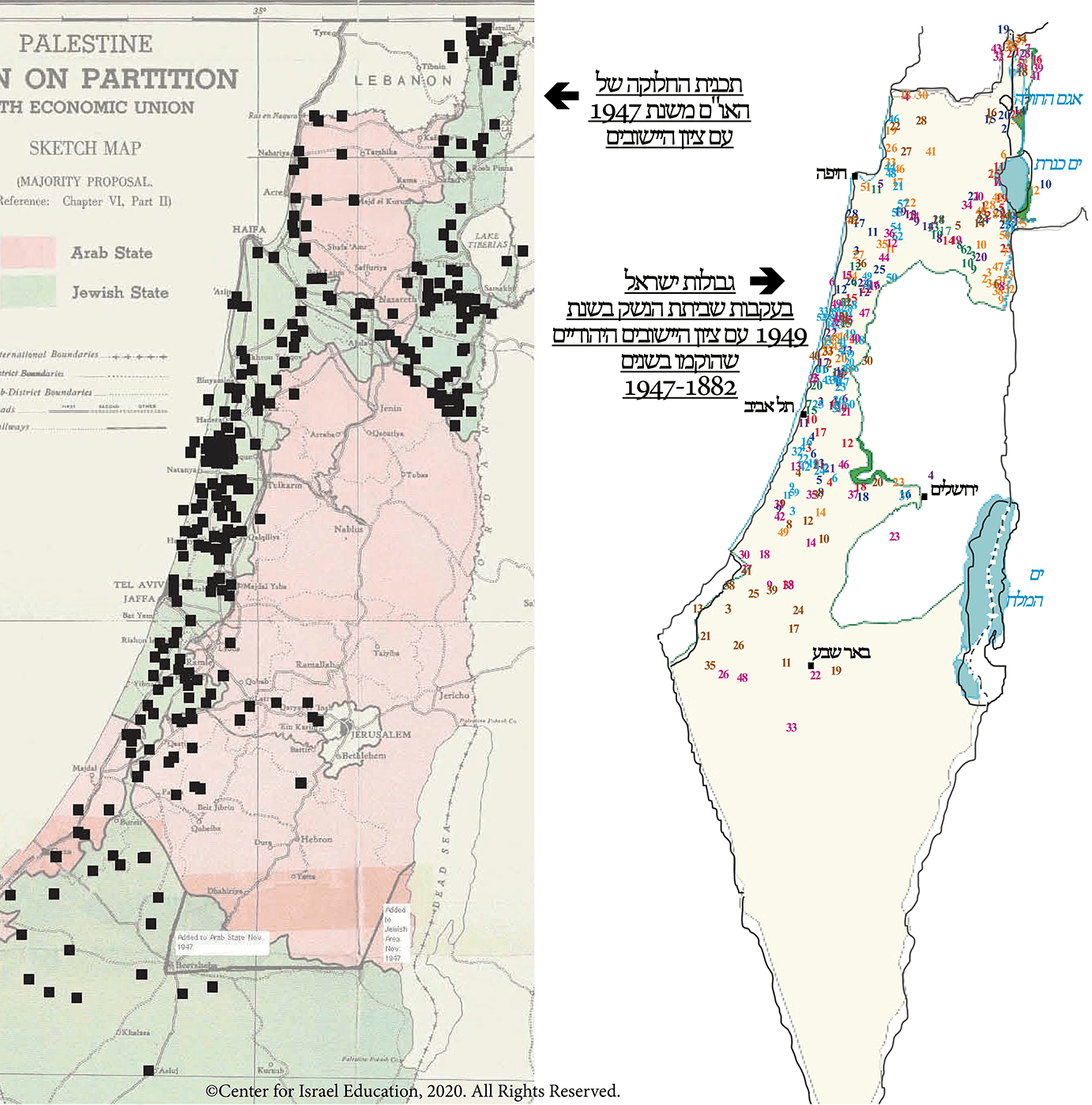

Land purchase and Jewish immigration were essential for economic growth. Both are explained in Forming a nucleus for the Jewish state, 1882-1947 and Zionist Land Acquisition; a core element in establishing Israel, not only describing the quantities of Arab land offers to Zionists, but their whereabouts which proved of strategic value such as areas near the headwaters of the Jordan River, along the coastal plain, on the Jerusalem to Tel Aviv Road, and in Beersheba. (The U.N. 1947 partition plan suggested Arab and Jewish states; the U.N. drew the map for two states based on 50 years of Jewish growth.) Jewish immigration to Palestine before and after World War I was a vital requirement if there was to be a Jewish state. Immigrants’ contributions to the economy, industry, education and political organization unfolded and grew the infrastructures needed for a viable Jewish state.

Immigration — the labor force catalyzes economic growth

At the end of WWI the Jewish population constituted 8% of the total population, by 1948 it was 33% of the total, with Jewish growth due largely to Jewish immigration. In Palestine, between 1922 and 1947, the Jewish sector of Palestine’s economy grew by 13.2% annually; by 1936 the Jewish sector earned 2.6 times more than the Arab sector. Stunning Jewish economic growth in Palestine evolved because there was a preponderance of single male immigrants, along with their high literacy levels, an ideological commitment to build new enterprises no longer constrained by restrictions previously imposed in former home settings, the availability of sufficient land and capital to generate enterprise development. The Jewish economy evolved business in rural and urban areas, and built small industrial zones. Jews contributed to growth in the building industries, in health care, education, culture, finance, and banking. They all were undergirded through capital investment. Jewish immigrants brought their own capital for the most part or were required to pay sums to immigrate to Palestine with those amounts going to the British administration.

Comparisons of Annual Percentage GDP Growth Rates, 1922 -1947

| Jewish sector in Palestine | United States | Britain | France | Germany | Japan | Italy | Brazil | Australia | Russia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP Growth Rate | 13.2 | 4 | 2–3 | 2–3 | 4–5 | 7–8 | 2–4 | 3–5 | 3–4 | 10–12 |

Note, there are no readily available statistics for Iraq or Egypt in the same period.

The impact of single male immigration was highly significant for the state in the making’s development. This phenomenon began after World War I, especially with the Third Aliyah (1919–1923) and continued through the 1920s and 1930s. The preponderance of males aided labor needs in agriculture, construction, and industry. By 1933, Jewish agricultural advancements were significant to have major impacts on local Arab agriculture. They were seen as a valuable labor force for the Zionist project, which required the physical development of the land. Women too participated but not at the levels of males in the work force. Many of the young men who immigrated were committed to the Zionist cause, or at least open to being swept into a dynamic of contributing to a newly evolving enterprise in as yet a fully defined Jewish homeland. This ideological drive was central to the success of the Zionist movement. Again, women played highly significant roles in defending Jewish demographic locations, while single males served in the emerging Jewish military organizations. A preponderance of single male immigrants had both short and long-term impacts on the demographic structure of Jewish Palestine.

Jews in the industrial sector

By 1927, Jews were already major participants in the industrial sector, despite Arabs owning a majority of industrial establishments. While Arabs owned 67% of industrial establishments, representing 56% of the total output, Jewish investments accounted for two-thirds of the output, highlighting the disproportionate role Jews played in economic activity (p. 176). Barbara J. Smith (1993) highlighted the rapid development of a modern industrial sector driven by Jewish immigrants. The industrial growth was largely shaped by the needs of Jewish settlers, not the Arab population. By the late 1920s, a modern, Western-style industrial sector had emerged, focused on consumer goods and providing employment for Jewish workers. (The Roots of Separatism in Palestine British Economic Policy, 1920–1929, Syracuse University Press, 1993, pp. 178 and 179.)

By 1939, the Jewish industrial sector had expanded considerably. The Jewish economy dominated industrial activity, with 872 Jewish firms employing 13,678 workers and additional small businesses providing employment to another 18,000. Jewish industries also accounted for a staggering 86% of total industrial output and 79% of the workforce (Survey of Palestine, 1946). The capital invested in Jewish industries surged from LP 4.39 million in 1939 to LP 12.09 million by 1942, reflecting a robust industrial growth.

Issa Khalaf, Politics in Palestine Arab Factionalism and Social Disintegration, 1939–1948, State University of New York at Albany, pp. 48–49.

During the Second World War, the Jewish economy grew even further. Jewish industrial output doubled, especially in industries related to the war effort. The war created almost a self-sufficient economy, with local production meeting the needs of both military and civilian sectors. In 1945, Jewish industries were responsible for 85% of Palestine’s total industrial production, with over 600 new enterprises founded during the war (Zionist Organization, 1946).

Capital Investment and Financial Contributions

From 1920 to 1945, Jews played a pivotal role in financing the development of Palestine. A considerable portion of the investment came from abroad, with the Keren Hayesod alone raising over L14.5 million by 1945, primarily from the global Jewish community (Kaplan, 1946). By the end of the Mandate, Jewish capital accounted for 60% of Palestine’s overall fixed capital formation, contributing significantly to industrial expansion. In the inter-war years, Jews invested 39.3% of their Gross National Product (GNP) annually into the economy, far exceeding the Arab sector’s 12.2% (Jacob Metzger, The Divided Economy of Mandatory Palestine, 1998). These investments fueled economic growth without relying on British taxpayer funds, largely coming from private Jewish capital, primarily through immigrant transfers. (Eliezer Kaplan, “Private and Public Investment in the Jewish National Home,” in J.B. Hobman (ed.), Palestine’s Economic Future A Review of Progress and Prospects, London: Percy Lund Humphries and Company, Limited, 1946, pp. 112–115.)

In 1948, during the War of Independence, Israel’s economy was bolstered by substantial contributions from the Jewish diaspora, amounting to $250 million. About 75% of the cost was raised domestically, demonstrating the strong financial support from both Jewish citizens and diaspora communities (Derek Penslar, “Rebels Without a Patron State, How Israel Financed the 1948 War,” in Rebecca Kobrin and Adam Teller (eds.), Purchasing Power: The Economics of Modern Jewish History Jewish Culture in Contexts, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015. pp. 186–187, 188, 191).

Jewish Contributions to British Revenue

Throughout the Mandatory period, the Jewish community played a highly significant role in contributing to the British administration’s revenue. In 1928, despite making up just 17% of the population, Jews contributed 44% of the revenue, a share that significantly outpaced their demographic proportion (House of Commons Debates, 1930). By 1944/45, Jewish contributions to government revenue increased to 65%, despite Jews representing only 32% of the total population, further reflecting the Jewish community’s economic importance in Palestine (Zionist Organization, 1946). The British used 80% of revenue collected during the Mandate to pay for their administration there. They built roads, ports, refurbished the Ottoman rail system and airports, and other infrastructure needs. With collected revenues, the British established a public health system that improved sanitation, reduced infectious diseases, and built hospitals and health clinics, mostly in urban areas. When the British left Palestine in 1948, the infrastructure that remained fell under Israeli control, yet it had been a majority of tax and other revenues from mostly Jewish sources during the Mandate that made it possible for Britain to sustain and build their presence in Palestine.

Potential for a Jewish State

By 1948, the economic nucleus necessary for the establishment of a Jewish state was in place. The Jewish economy had achieved significant industrial growth, capital investment, and was undergirded by a robust workforce. Despite the economic dominance of the Jewish sector, geographic separation between Jewish and Arab communities had solidified, with Jews primarily residing along the coast and in the valleys, while Arabs inhabited the interior. Spatial separation of the two communities had evolved from before World War I, with Arab-Jewish interaction occurring modestly over the subsequent three decades. (Yossi Katz, Partner to Partition The Jewish Agency’s Partition Plan in the Mandate Era, Frank Cass, 1998, p. 19.) The Jewish economy had become close to self-sufficient, particularly in industrial production, capital investment, and revenue generation. The economic infrastructure was present, not robust, but sufficient to support the establishment of a Jewish state. The British for their part had already in 1937 in their Peel Report suggested that for possible future communal harmony it would be better for each community to have their own political entity.

The development of an independent economic base, largely financed by Jewish diaspora and immigrants, made the Jewish community well-positioned to navigate the transition to statehood in 1948, albeit with difficulties. The capacity of the Jewish economy to contribute to the war effort, create jobs, and generate substantial revenue for the British administration demonstrated that an economic nucleus for a Jewish state had been in the making for decades. This is the thesis that Jacob Metzger makes in The Divided Economy of Mandatory Palestine, 1998. Thus, by 1948, in many areas a formidable Jewish economy had evolved into an almost self-sustaining entity; Zionists had created multiple organizations and institutions in the building trades and health care, developed Jewish land purchasing and land settlement entities, unfolded a Jewish Agency for Palestine in 1929 (out of the World Zionist Organization founding in 1897), banks, small industries, marketing firms, and self-defense entities such as the Haganah and Palmach, all derived from self-empowerment while investing their own capital in their evolving state structures. Zionists evolved their geographic, demographic, and infrastructure development without the force of law compelling them to do so. Zionists mobilized themselves in multiple spheres, ensuring supply of essential services, and notably blurring the distinction between eventual soldier and citizen. When the United Nations recommended the partitioning of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states on November 29, 1947, dividing the land area as a means to provide self-rule for both populations, it was no accident that the UN suggested an economic union (mentioned fifteen times in the document) be created between the two proposed states. It was understood that the Arab state would not be viable economically unless it were tied to the proposed Jewish state’s economy.

— Ken Stein, March 12, 2025