In pursuing its central political objective to control and lead the Palestinian Arab quest for statehood, the Palestinian Authority (PA) headed by Mahmoud Abbas is delighted to have multiple countries endorse a two-state solution. Affirming...

Latest articles from CIE

Board of Peace Inaugural Meeting, 2026: Hamas Disarms for Redevelopment, or Gaza Returns to War

The first meeting of the Board of Peace convened under the Trump ceasefire for Gaza offers grand plans for reconstruction and a vibrant, peaceful future for Palestinians but depends on the disarmament of Hamas.

Stein: The Causes and Consequences of the 2023-2025 Hamas-Israel War (transcript)

CIE President Ken Stein addresses what is and what is not known about why Hamas attacked October 7, 2023, why Israel was caught off guard, and what happens after the war across the region.

Controversies Uncool for Israel’s Olympic “Shul Runnings”

Israel wasn’t expecting gold, silver or bronze in the 2026 Winter Olympics, but it also wasn’t expecting controversy to mar the happy story of its first Olympic bobsledders.

Evaluating the 2023-2025 Hamas-Israel War and Its Consequences (video, 44:06)

CIE President Ken Stein briefly reviews the 2023-2025 Hamas-Israel war and examines the short- and long-term consequences.

American Officials on Zionism, Israel, the U.S.-Israeli Relationship and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1922-2026

Using published archives, press conferences, speeches and numerous interviews, this compilation of quotations traces how official American views on Zionism and Israel have evolved over a century.

Secretary of State Shultz’s Speech to Washington Institute, 1988: Last Israeli-Arab Peace Pitch From Reagan Administration

In the waning days of the Reagan administration, Secretary of State George Shultz pushes for U.S.-mediated peace negotiations, including Palestinians, and offers the outlines for a resolution to the conflict.

Scholarly Praise for CIE’s Website

The following scholars, academics, think-tank leaders and offer their high praise for the CIE website, israeled.org. “The CIE website is an indispensable and unique resource for anyone interested in Israel and the Middle East. Balanced…

#155 Contemporary Readings January 2026

Maya Rezak and Ken Stein, February 8, 2026 Hussain Abdul-Hussain, “Why Is Saudi Arabia Abandoning Peace?” The National Interest, January 23, 2026. Oded Ailam, “‘The Glass Wall’: How Israel Turned Intelligence Into an Insurance Policy…

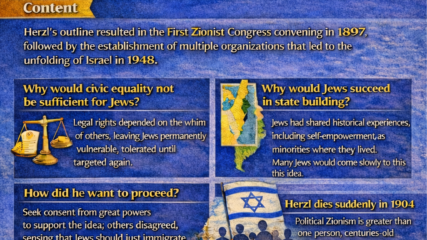

9 Key Questions About Theodor Herzl’s “The Jewish State,” February 14, 1896CIE+

Nine questions guide key understandings about Theodor Herzl’s “The Jewish State.”