Source: State of Israel Government Yearbook, 5714, November 1953, Government Printing Press, pp. 1-50, excerpts here.

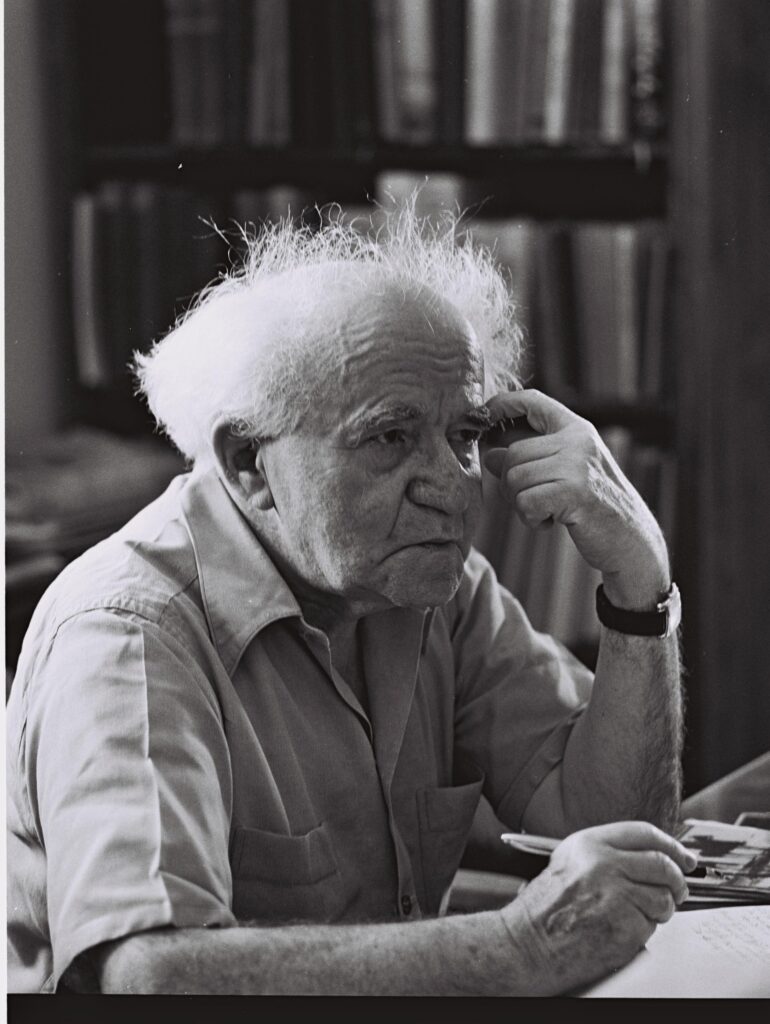

David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister (most of 1948 to 1963) and previously head of the Jewish quasi-self-governing authority under the British Mandate, wrote a 50-page summary of the Jewish people’s origins, their attachment to the Land of Israel, their survival, the causes of Zionism, and how a Jewish population with diverse geographic and ideological backgrounds stayed together for the establishment of the independent state in 1948.

The Jewish nation’s DNA included facing relentless challenges marked by dispersal, ostracism and hatred by many peoples and often being regarded as undesirable. Despite these adversities, Israel’s establishment “symbolizes a remarkable victory against all odds — a culmination of the Jewish people’s tenacity and unyielding spirit.”

As a political leader and Jewish historian, Ben-Gurion notes that the state enabled Jews from across the world to find a homeland where they could live freely and with dignity; Jews wished to escape a life of dependency and join the collective effort to build a sovereign homeland. He claims that the state unified Jews worldwide and transcended previous divisions over the feasibility or necessity of a Jewish state, all the more remarkable because the population represented various ideologies and backgrounds, marking an unprecedented moment of Jewish unity and pride.

“Zionists and non-Zionists, pious and agnostic, conservative, liberals and Socialists, all were united in their joy and pride.” The state introduced new tensions, as the various factions within the Jewish community were now compelled to operate within a common framework of duty and law, amplifying internal conflicts. Challenges enforcing unity within the state remained, but an unprecedented moment of collective will and national responsibility flourished.

He reviews Zionism’s origins from two sources: the Messianic Hope, rooted deeply in Jewish history and faith, and the more recent political and nationalistic movements that arose in response to the changing political landscapes of 19th-century Europe. The Messianic Hope, tied to the biblical promise of the Land of Israel, provided spiritual strength and consolation to Jews throughout centuries of exile. In contrast, the political Zionism of the 19th and 20th centuries, influenced by European nationalism and the social changes brought by the industrial revolution, gave rise to a more practical and organized movement aimed at re-establishing a Jewish state.

In this brief excerpt Ben-Gurion warns of possessing the wrong assumption of victory because the ultimate battle for the Jewish people’s future is ongoing. And he notes that “an inadequate knowledge of what the State has achieved is harmful to the capacity of the nation for living its life as a State, but no less injurious is the false assumption that Jews have already achieved victory in their historic struggle.” Critical in his analysis is the axiom that Jews had no spiritual link with the countries and peoples with whom they dwelt for centuries, for the Jews lived as exiles, retaining their religious/national identity within those locations.

Restrictions on Jews forced them to live together, developing a sense of association and common responsibility promoted by the legal discrimination of their neighbors upon them. He notes that “no state can exist without authority, compulsion and majority decision, yet it cannot base its existence solely on authority, compulsion and majority decision. It derives its vitality, strength and cohesion from the general will of the nation, from its common historical needs, from mutual responsibility, from the inner unity which bridges differences and contradictions. The State of Israel brought all the residents of the country into a framework of duty and compulsion. The relation between individual and community is no longer a matter of free choice and agreement alone.”

Ben-Gurion, perhaps also including Theodor Herzl and Chaim Weizmann, had the most profound and central role of any person in Israel’s establishment. The essay captures his and the state’s early essence, with his wonderment and pragmatic realization that the state and Zionism were not remotely close to being finished, nor having succeeded in the quest for the Jewish people’s normalization.

— Ken Stein, September 2, 2024

The Jewish People has been struggling for its survival, unity and independence ever since it came into being, until our own days. This is the daring and tragic struggle, unique in human history, of a small nation, alone, dispersed, ostracized, hated by many peoples and regarded as undesirable by almost all others; and it appears to have been crowned with victory by the rise of the State of Israel. Against all the logic of existence, without parallel in the story of the nations, to the dissatisfaction of mighty forces, against the armed and militant opposition of all the neighbouring countries, those who returned to Zion have established a Jewish State in the original home of our people.

In accordance with its basic constitution and the deepest desires of those who founded and established it, the new State has opened its gates wide to every Jew who wishes to be done with a life of dependency elsewhere and to join those who are building the homeland and living a free and upright Hebrew life. The Jewish people throughout the dispersion has opened its heart to the State of Israel in love and esteem; many generations have gone by since we saw so all-inclusive, deeply rooted, joyous and proud a Jewish unity as was revealed in full measure on the establishment of the State.

The debates and discussions as to whether the “National Home” and the Jewish State were necessary and practicable, or harmful and dangerous, which had divided and disturbed the House of Israel for more than two generations, came to an end and vanished. Zionists and non-Zionists, pious and agnostic, conservative, liberals and Socialists, all were united in their joy and pride. The small Jewish population of this country had become a sovereign people. Every Jew in the Exile who has had enough now finds the State of Israel waiting to receive him willingly and lovingly. When the returning newcomer sets foot on the soil of the Homeland in order to settle there, he immediately and ipso facto becomes a citizen enjoying full rights in our State, like the old settlers and born inhabitants.

Jewish obstinacy, unflinching and unsubmissive, seemed to have celebrated its complete victory, and the ancient Jewish people might at length be supposed to have reached the historic bourne of its desire. The ingathering of the exiles, to be sure, has just begun, and there is still a vast amount of building-up to do, but the eternal wanderer has a secure haven, and the longings of generations and centuries have been fulfilled. Jewish sovereign power has been established In the Homeland; henceforward the independent existence of the nation in its country is secure; and the unity of the Jews in the Exile has been strengthened.

It would be hard to exaggerate the importance of these two great and highly significant facts. In spite of the difficulties, hardships and failures, the five years of Statehood have served to show what a nation can achieve in its own land when it is in charge of its own affairs. Many of those engaged in the actual work lack the perspective required to appreciate the magnitude of the achievements, the feats of creative initiative, which have been brought about during these five years, and most of the country’s citizens are not fully aware of the vast amount actually accomplished during these few obstacle-strewn years, in security, development, settlement, building, industry, education and the advancement of the individual in Israel.

An inadequate knowledge of what the State has achieved is harmful to the capacity of the nation for living its life as a State, but no less injurious is the false assumption that we have already achieved victory in our historic struggle. Only the final battle brings the victory, and the State of Israel and the Jewish People have not yet fought the final battle. The establishment of the State has not completed the redemption of the people. We have not yet secured its survival and unity in the Exile, nor have we even brought about inner unity within the country itself. The State has straightened the backs of the Jewish people in the world and permits any Jew who so desires to live a free and independent life. Yet the establishment of the State has served to make the problem of our survival and unity more acute and grave, both here and in the Diaspora.

Zionism derives from two sources. One is deep, irrational, lasting, independent of time and place, and as old as the Jewish people. It is the Messianic Hope. Its beginnings go back to the story of the first Hebrew, who was told: “And I shall give thee and thy seed after thee … all the land of Canaan as a possession for ever.” This promise to inherit the land the Jewish People saw as part of an everlasting Covenant between them and their God. In this land the fathers of the nation had gone to and fro. Unto it their sons returned when they came forth from Egypt. Here the tribes of Israel were united into a single people, and here was shaped the historic character of the nation. In this land they fashioned everlasting works, and in it was made manifest one of the most remarkable and tremendous phenomena of human history — Hebrew prophecy. Here were first heard the tidings of the coming redemption, redemption of nation and world alike. These Messianic tidings became the source of life, strength and consolation for the Jewish people in all its harsh and cruel sufferings, and throughout its many long wanderings.

The nation was exiled from its land. It returned and then was exiled afresh. Yet after being cut off a second time from the Land of their fathers they continued to pray three times daily: “Sound the great ram’s-horn for our freedom; raise high the banner to gather in our Exiles; and gather us together from the four corners of the earth. … Restore our Judges as in the beginning and our counselors as at the first. … And mayst thou return in mercy unto Jerusalem thy City and build her up speedily, in our days, for all eternity; mayst thou speedily establish the seat of David thy servant in her midst … and may our eyes envisage thy merciful return to Zion”.

The faith in the coming of the Messiah became a basic tenet of Judaism, and day by day every Jew would repeat: “I believe with faith whole and entire in the coming of the Messiah, and even though he may delay, I shall nevertheless await his coming every day”. The land of the fathers was captive and desolate. One after the other foreign conquerors held sway therein, and Jews were hundreds of years and thousands of miles away; but the State of Israel was planted and rooted deep in their hearts and their souls, and they took that State with them wherever they might go.

The second source was a source of renewal and action, the fruit of realistic political thought, born of the circumstances of time and place, emerging with the changes which came about in European nations during the nineteenth century, and under the influence of those changes on Jewish life.

The character of liberation enunciating the Rights of Man and Nation which the French Revolution bequeathed to Europe; the national revival movements which developed among several European peoples and aimed at unity and independence (in Italy, Germany, Poland, the Balkans and elsewhere); the new means of transport and communication which brought near the distant and made speedy movement possible, in the form of steamships, railways, telegraph, telephone and daily press; the rise of the working class and its struggle for a new social system; the mass migration from Europe to overseas countries; all these helped to bring about a new direction in Jewish thought. They raised the status of the Jews even in the countries of discrimination, legal restrictions and anti-Semitism. They increased the will to national liberty and human equality and revealed the possibilities to be found in mass migration.

The Messianic hope, which for scores of generations had worn a religious garb and had appealed to a force above Nature, now changed its religious and passive form and became political and national. Furthermore, it was directed inwards, becoming the organized force and implementing will of the Jews themselves.

Zionist leadership came from Western Europe, from the assimilated Jewry which had been affected by anti-Semitism and which understood the ways of politics; yet Zionism drew its popular, its inner strength from the Jews of Eastern Europe, from the masses who lived a full life within a true Jewish culture. They did not need to return to Judaism like the Zionists of Western Europe, for they were Jews from birth, and their Judaism was natural and deeply rooted. Almost all their spiritual nourishment reached them through the ancient and modern Hebrew language, the religious and secular Hebrew literatures, and the Yiddish vernacular. Above all, their principal aspiration and hope was a free homeland of their own.

These Jewish masses felt no spiritual link with the countries and peoples amid whom they dwelt. For them these counties were Exile, oppressive and tyrannous Exile, and all their hope was to forsake that Exile. During the eighties of the nineteenth century the great migration began from the lands of Eastern Europe.

Until the thirties of the twentieth century the migrating masses flowed chiefly to the United States of America. From the middle of the nineteenth century a small stream had moved to the Land of Israel, as a continuation of the unceasing attempts to return to Zion which had continued throughout all ages.

During the eighties of the nineteenth century a Jewish mass migration began from Europe, particularly Eastern Europe, and two new centres emerged, one in the United States of North America, great in number and economic and political importance, and a second, far smaller — yet more vital, because of its quality and influence on Jewish destiny — the new Jewish population or Yishuv of the Land of Israel.

Between 1881 and 1914 three million Jews left Eastern Europe, and another million from 1914 till the Second World War. Until 1930 the current of mass migration streamed chiefly to North America. During this half-century (1880-1930) nearly three million Jewish immigrants entered the United States. At the beginning of the nineteenth century United States Jewry had mustered only about two thousand souls, while in the middle of the century the number had not been more than 50,000. By the end of the century their number exceeded a million, and by 1939 it amounted to 4.8 million.

Important communities were also established in other lands of the American continent, the largest in the Argentine and Canada. Jewish migration also reached South Africa, where the number of Jews rose from 500 in 1850 to 100,000 in 1935.

In spite of this mass migration the greater part of the Jews continued to be concentrated in Europe until the Second World War, and until the First World War that Jewry was in all respects the centre of Jewish life throughout the world; it was the source of its strength and determined its character.

Until the nineteenth century almost all parts of Jewry followed the traditional form of life and worship, both in the Orient and in Europe. This general adherence to the laws and religious customs of Israel served to strengthen dispersed Jewry and hold it together. The Jews felt their Jewish singularity and mission as something vital, although this feeling did not find expression in a modern national ideology but was garbed only in religious dress. The traditional education which every Jew was at pains to secure for his sons, though not for his daughters, provided the nation, consciously and unconsciously, with a sense of unity and historic continuity. The Hebrew language, though not a vernacular, lived in the heart of the people, for it was the language of prayer and of the literature, which was based on the Torah, developing steadily and serving as both the written as both the written language in the internal transactions of the communities and the “international” means of communication between Jews of various countries. The religious festivals, steeped in national memories, were a kind of substitute for a common life in the Homeland. No more than a few thousand Jews dwelt in the Land of Israel, yet every Jew bore the Land of Israel in his soul, and the distant land of his fathers was nearer to his heart than the land in which he lived and grew. Not the faintest question awakened in the Jewish heart as to why and wherefore they were Jews. The fact that they lived largely in towns, and were engaged in special callings and occupations, helped to hold them together and increased the Jewish sense of association and common responsibility, which were also promoted by the legal discrimination and the animosity of their neighbours, from which the Jews suffered at that period.

Following the emancipation and the dissemination of enlightenment and Western culture during the nineteenth century, the loyalty to the tradition faith and the accepted religious laws was shaken and discarded among large parts of European Jewry, first in Western Europe and afterwards in the eastern part of the continent. The upper strata began to employ the vernacular of the dominant peoples, and there was an increasing desire to resemble non-Jews in clothing, behaviour and education. The process of assimilation gained momentum in the western lands, but the masses in Eastern Europe remained faithful to the traditional Jewish ways of life and education.

In Western Europe the process of assimilation met with waves of the Jew-hatred labelled anti-Semitism, a misleading and corrupt term apparently coined by assimilatory Jews as a euphemism. The Jews of the West lost on the swings as well as on the round-abouts, and a vacuum was created in their lives. In Eastern Europe the Jewish National idea, the love of Hebrew and the yearnings of the historic homeland inherited the place of religion, the hold of which had weakened.

Rabbinical literature, which had continued to gown throughout the ages and had employed Hebrew intermingled with Talmudic Aramaic, was not supplemented by a secular Hebrew literature based almost exclusively on the language of the Bible. The Hebrew novel came into being, there was a new efflorescence of Hebrew poetry, whose voice had scarcely been heard since the Golden Age in Spain in medieval times. Scientific and general works were written in or translated into Hebrew, a Hebrew Scientific and general works were written in or translated into Hebrew, a Hebrew press was founded dealing with the daily affairs of Jews and non-Jews alike, and concerned particularly with political and international affairs.

Never in Jewish history has the unity of Jewry been demonstrated more fully than at the proclamation of the State in our own day. … On the eve of the establishment of the State the Jewish inhabitants of this country were quite possibly the most divided and disunited of all Jewish population groups throughout the world. In no country was it possible to find so variegated and colourful an assembly of communities, cultures, organizations and parties, beliefs and opinions, conflicting international ideologies and orientations, social and economic interests and differences, as in the Yishuv of the Land of Israel — itself the child of an ingathering of exiles and centre of all the rifts and rents in Israel. Yet when independence was proclaimed it seemed as though all barriers were destroyed, and the Declaration of Independence was signed by representatives of all parties in Israel, from the Communists, who had always fought against Zionism as something reactionary, bourgeois, chauvinist and counter-revolutionary, to Agudat Israel, which regarded every attempt to bring about the redemption of Israel by natural means as wanton heresy and an undermining of Jewish faith and custom.

No state can exist without authority, compulsion and majority decision (except, in the case of the latter, a totalitarian state with one-man rule). Yet no state can base its existence solely on authority, compulsion and majority decision. It derives its vitality, strength and cohesion from the general will of the nation, from its common historic needs, from mutual responsibility, from the inner unity which bridges differences and contradictions. This is true of every state, and doubly so of the State of Israel. This is no state of its inhabitants and for its inhabitants alone. It is not the state of a built-up country with a fully functioning economy. It is not a state whose existence is welcomed by its neighbours, or to which there is no objection on the part of great powers. Those who live in it are no more than the nucleus of the people for whom it was established. Most of its area is arid and desolate and needs development. Its economy is at its very beginnings. All its neighbours are planning how to destroy it. Great forces in the world view it with displeasure; and the objectives in absorption, development and security which are incumbent on such a state are not going to be achieved by the power of compulsion enjoyed by the authorities alone. Without tense and unremitting effort on the part of all its inhabitants and the assistance of the entire nation and Ingathering of Exiles is impossible, the desolation will not be rendered fertile, security will not be established.

The establishment of the State has accentuated difference which previously existed in the Yishuv precisely because the State introduced a mutual bond of duty and the inclusion of every individual in Israel within a common framework. In the Yishuv there were God-fearing and free-thinkers, religious Zionists and the anti-Zionist, orthodox Jews, workers and employers, those who were faithful to the Zionist vision and others who disregarded it, believers in the West and in the East, rationalists and followers of the Torah, cultured persons and those who never had an opportunity to study, members of mutually opposed and backward communities, natives and new-comers, townsfolk and countryfolk. This variegated Yishuv did not entirely lack joint and inclusive organizational instruments comprising the majority of its members, and on occasion it was capable of acting as a single unit. Yet all the public instruments were voluntary, not compulsory. Those who so desired accepted them, while those did not so desire simply withdrew. The Vaad Leumi, the Haganah, the Zionist Organization, the Histadrut, the communities, and Rabbinical Office and the other bodies, were all based on voluntary membership, personal assent and an act of free-will. The territorial authority was alien and frequently served as a unifying factor when the entire Yishuv was opposed to its ways aims.

The State, however, brought all the residents of the country into a framework of duty and compulsion. The relation between individual and community is no longer a matter of free choice and agreement alone. As far as most matters were concerned the various groups which existed in the Yishuv, with their opposed and contradictory views, tendencies, habits and interests, could act as they thought fit, without feeling or stressing the differences between themselves and others, and without internal conflict. Once the State was established they were all brought together, transformed into a closely combined unit, whether they so desired or not; they were subject to a sovereign entity which imposed upon them its laws and instructions. The power of free choice was replaced by the compulsion of duty; the individual and the community could no longer do as they chose, with the result that differences and conflicts grew far more acute.