Kenneth W. Stein, “The Arab-Israeli Peace Process,” Middle East Contemporary Survey, Vol. XXI, 1997, Bruce Maddy-Weitzman (ed.), Westview Press, pp. 71-109.

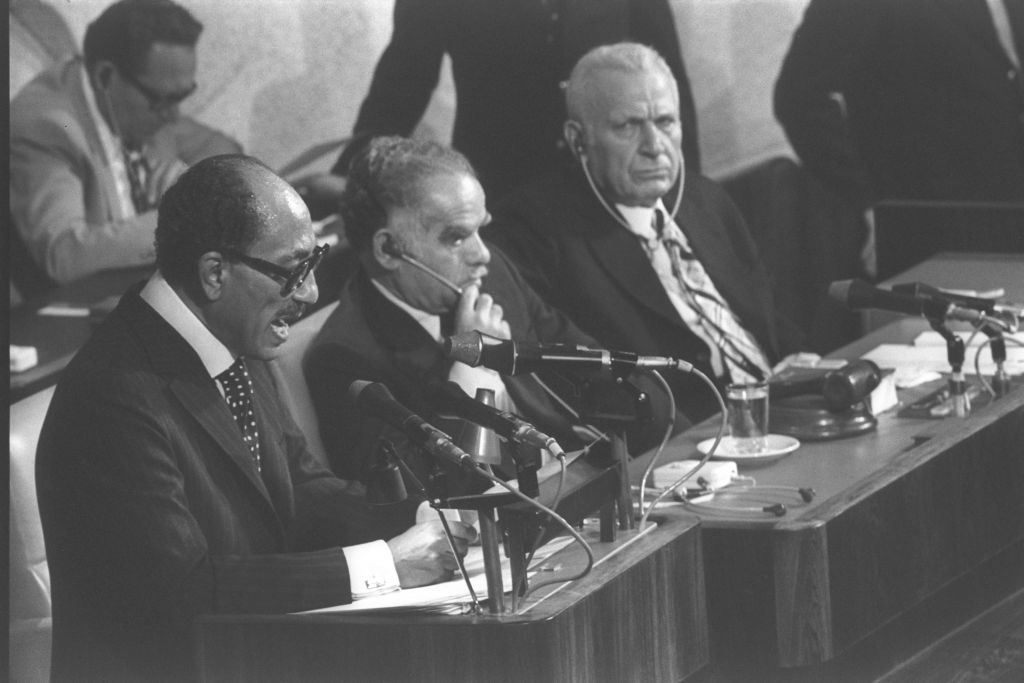

On a macro level, in 1997, Israel and much of the Arab world spent the year carping at each other, meeting, and struggling to define structures that would determine present and future relationships. The final-status deadline of May 1999 for completion of Palestinian-Israeli negotiations influenced virtually all policy choices, diplomatic contacts with one another, and the degree of their frustration levels. Typical of the atmosphere surrounding Arab-Israeli relations in general were the virtually nonexistent anniversary celebrations in the Middle East of former Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat’s historic visit to Jerusalem 20 years earlier. The peace process was a medicine that one had to take, but did not have to like. Arab states and Israel remained emotionally and physically far apart. The barbed wire and no man’s land that divided Jews and Arabs in the city of Hebron characterized the jagged and sharp lines that personally and diplomatically separated them. In the four intervening years since the 1993 Palestinian-Israeli Declaration of Principles (DoP) was signed, Israelis and Arabs were still, at best, grudgingly accepting the notion of mutual coexistence. For a vocal, potentially ominous, and significant Arab minority, Israel remained anathema, its policies vilified, its territories preferably truncated, its legitimacy nonexistent. In the West Bank and Gaza areas, it was estimated that since Oslo was signed, the economy dropped an average of 8% in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita per year, adding fuel to the fire of the Arab opponents of Oslo, and undermining its supporters. To be sure, more Arab states and publics did not trust Israel, its leaders, or its policies. However, that did not mean that they were working feverishly to wage war and destroy the Jewish state. For some Israelis, the Arab world could never do enough to satisfy Israeli security requirements. With the expense of great emotion and frustration, the Arab-Israeli conflict was becoming a series of still not clearly defined Arab-Israeli relationships. The peace process was an arduous work in progress; it climbed a slippery slope. The Palestinian-Israeli relationship was in the incubation stage; it was still half-pregnant. During the year, American involvement in the peace process changed from an essential intermediary to an engaged mediator, active broker, umpire and subtly to quiet referee.

By any objective analysis of the Arab-Israeli peace process, the year was a bad one. It ended much worse than it began. Except for the Hebron agreement signed between Israel and the Palestinian Authority (PA) in January involving the transfer of 80% of the city from Israeli to Palestinian jurisdiction, little progress and a large amount of ill will characterized Israeli-Arab relations. Palestinian-Israeli discussions were intermittent; they were repeatedly shut down, reopened, suspended, and then rejoined.

Read the Full Article in a Printable PDF