June 16 and 17, 1980

Source: Foreign Relations of the United States 1977–1980 Volume IX Arab-Israeli Dispute August 1978-December 1980, p. 1258 Start -pp. 1271

Background

As a result of the 1948 War, Israel was established, Arabs from Palestine fled their homes as refugees, Jordan took over the West Bank and a portion of Jerusalem, Jewish refugees fled from Arab lands to Israel. A vast number of refugees fled to Jordan and changed its demography, giving Jordan a majority Palestinian population, as compared to the smaller number of east Bank Jordanians who have formed the Kingdom in 1921 under the British Mandate. After the 1948 War. four separate armistice agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. In the 1950s and 1960s, there were dozens of cross-the-border skirmishes between Israel and these neighbors, some incidental and others harsh and brutal on all sides. Before the 1948 war and sporadically through the 1960s and into the 1980s and 1990s, Israeli and Jordanian leaders met secretly about security and other matters.

The most prominent theme in their intermittent discussions was the opposition to Palestinian political or strategic control over the West Bank. Jordan’s Emir Abdullah in the 1930s entered into lease agreements with the Jewish Agency land brokers for the settlement of Palestinians away from growing Jewish rural settlements. Little came of that idea. In the 1947-1950 period, Jordan and Zionist leaders collaborated to keep the land in Palestine in their respective hands, and away from the Palestinian Arab leadership led by the Mufti of Jerusalem. When the PLO was established in 1964 by the Arab League led by Egypt’s President Nasser, Jordan was now confronted by a formal Palestinian organization that sought through “armed struggle” the liberation of all the area held by Israel since 1948. Jordan and the PLO evolved into becoming very keen and very open and angry competitors. The PLO knew it had a major Palestinian constituency living in Jordan, a population that was often highly sympathetic to the idea that all of Jordan and all of Palestine should comprise a Palestine of the future. In the mid-1960s secret talks between Israel and Jordan occurred again, seeking to agree on mutual interests in the use of the Jordan River and other strategic concerns.

In May and June 1967, Israel tried but failed to keep Jordan out of the war through requests made by the U.S. and by the U.N. This was to no avail. In the June 1967 War, Jordan lost the West Bank and her control over parts of Jerusalem to the Israeli success in the war. The PLO always at odds with the King of Jordan and Jordan’s very existence, sought but failed to overthrow the Jordanian government in September 1970 in a very brutal conflict where thousands were killed in what became a Jordanian-Palestinian civil war. When it looked like Syrian troops were prepared to enter Jordan to assist in King Hussein’s overthrow, the U.S. and Israel concertedly acted to prevent that intervention, with Jordan persevering over the PLO fighters, resulting the PLO being forced from Jordanian lands. After the 1973 War, and again in 1974 and 1975, Jordan was told by the Arab League that it could not speak on behalf of the Palestinian people. The prerogative was assigned to the PLO. Jordan’s relations with the PLO remained virulently hostile; Syria’s relations with Jordan remained angry, still lingering from the attempted actions by Syria in the 1970 Civil War, where Palestinians and the PLO sought to topple King Hussein. Jordan remained insulted that after the October 1973 War, when Henry Kissinger led the American diplomacy, little or now effort was made to find even a small disengagement agreement between Israel and Jordan like the ones negotiated between Israel and Egypt and Israel and Syria. Jordan carried negative chips on its shoulder for the Syrians, the PLO, the Arab League, and the U.S. government. These animosities between Arab entities were open and raw in January 1977 when the Carter administration took office.

King Hussein, Jordan and the Carter administration

For its part, Israel wanted nothing to do with the PLO and preferred if it had to negotiate some withdrawal from the West Bank or have a territorial compromise in exchanging land for peace, should that eventually evolve, Jerusalem preferred to negotiate with the Jordanians as the address for discussion.

And yet, when the Carter administration came to office it sought to find a comprehensive resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict, which meant urging Israel to give up the West Bank so these lands could become the geographic center for a Palestinian homeland or entity. Neither the Labor Party nor the Likud Party in Israel in Israel wanted to turn land over to the PLO or see the establishment of a Palestinian state. For that matter the Jordanians were not interested in seeing the evolution of a Palestinian state and had real fear that an international conference that Carter wanted to convene would push a Palestinian entity, that would threaten to upset Jordan’s carefully sustained demographic balance.

Nonetheless, the Carter administration right through the end of the negotiations of the September 1978 Camp David Accords sought to push Israel into some process that would evolve into Palestinian self-rule where Israel would ultimately give up territory. At Camp David, Egypt’s Sadat was so intent in having an agreement with Israel and having the Sinai Peninsula returned to Egyptian sovereignty in a bilateral agreement with Israel, that he convinced President Carter that Egypt could speak authoritatively on behalf of the Jordanians and the Palestinians, both of whom were not physically represented at the Camp David discussions. Carter believed Sadat’s claim that he could speak for Hussein and Jordan. This was not the case. Once again, Jordan was taken for granted as Kissinger had after the 1973 war. Hussein would have nothing to do with a political process that could undermine his kingdom and that included the establishment of a Palestinian entity, that for example might control the Holy Sites in Jerusalem

At the September 1978 Camp David negotiations, two accords were signed: one an Egypt-Israeli agreement that provided a framework for evolving a peace treaty between Israel and Egypt predicated on Israel’s withdrawal from Sinai and Israel receiving a peace with Egypt.; and Egyptian President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Begin also signed with President Carter as witness, a second agreement regarding future negotiations over the West Bank and Gaza Strip in which Jordan would play a role facilitating Palestinian autonomy, something politically short of self-determination. Jordan was not at these negotiations; King Hussein was snubbed again. The Carter administration assumed Sadat could speak for the Arab world and the that the Jordanians and the PLO leadership could agree on who would have the lion’s share of influence in shaping a potential Palestinian entity in the West Bank that would, or could, or should emerge from implementation of Palestinian autonomy.

After the Camp David Accords were signed, Jordan’s King Hussein sent a letter to President Carter in which he said, “I’m all for peace with Israel and all for comprehensive peace with Israel and I wish you well at Camp David. Don’t put me in the impossible position of having to support a separate peace between Israel and Egypt, because I can’t. It would be untenable for me to be in these negotiations. I won’t have the PLO on my side.” Nicholas Veliotes, who was the U.S. ambassador to Jordan at the time, recalls with great detail how sour Jordanian-American relations were in the months after the Camp David negotiations.

By Passing the Palestinians

At these June 1980 Washington meetings. the first time Hussein and Carter had met since 1977, Hussein explained to Carter that Jordan viewed Egypt as having a “moral responsibility” towards all Arabs and so when Sadat backed off from declaring the need for Palestinian self-determination at Camp David, it came as a shock to him. (It is not certain that Hussein actually meant what he said to Carter here, because deep distrust and disdain still existed between Jordan and the PLO.) Carter explained that he and Sadat did not abandon the topic of Jerusalem, they simply “went round it.” Hussein noted that without a commitment from Israel that the end goal would be self-determination. Jordan couldn’t join any talks, he said, and that they saw themselves as helpful, not obstructionist. Hussein could say this because he knew the Israelis absolutely opposed a Palestinian state and Palestinian self-determination. Carter after the Camp David negotiations made it quite clear that he thought the Jordanians were obstructionist, a viewpoint that his national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, thoroughly believed as well. While Carter insisted that a bilateral agreement with Egypt was the best route, it was plain that Hussein saw it differently. While the U.S. and Jordan apparently mended their “public fences,” it took another decade for U.S.-Jordanian bilateral relations to warm up. That happened in the signing of the Jordanian-Israeli treaty in 1994, where still there was no Palestinian state in the works. Jordan made its peace with Israel and did so by bypassing the PLO and Palestinian aspirations. Egypt’s Sadat had done that in 1979 in his treaty with Israel. And Arab Gulf states and four other Arab countries would reach agreements and treaties with Israel in 2020 in the Abraham Accords. several years for warm relations to again characterize the bilateral Jordanian-U.S. relationship.

Carter and Hussein had a second meeting the following day. The memorandum of that conversation may be found at the end of this first meeting below.

— Ken Stein, March 10, 2023

SUBJECT

Summary of the President’s First Meeting with King Hussein of Jordan

PARTICIPANTS

President Jimmy Carter

Secretary of State Edmund Muskie

Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs

Ambassador Nicholas Veliotes, U.S. Ambassador to Jordan

Ambassador Sol Linowitz, Personal Representative of the President for Middle East Peace Negotiations

Harold Saunders, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs

Robert Hunter, National Security Council Staff Member (notetaker)

His Majesty Hussein I, King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

His Excellency Sharif Abdul Hamid Sharaf, Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan

His Excellency Ahmad Lawzi, Chief of Royal Court

Lt. General (Ret.) Amer Khammash, Minister of Court

Lt. General Sharif Zaid Bin Shaker, Commander in Chief of the Jordan Armed Forces

His Excellency Fawaz Sharaf, Ambassador of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan to the United States

(The President and His Majesty met briefly in the Oval Office, then joined the others in the Cabinet Room at 10:40 a.m. Throughout, King Hussein addressed the President as “Sir.”).

The President began by recalling his last meeting with King Hussein in Tehran at New Year’s 1977 [1978].

The Prime Minister noted that His Majesty had just been talking about that last meeting in Iran.

The President said that he was pleased and honored to have His Majesty come here again. He (the President) had said in his welcoming remarks that relations with Jordan are extremely important to us. They are founded on shared commitments and ideals, which have not and will not change. He was sorry that there had been this series of delays in his (the King’s) coming here. But he looks eagerly to having this chance to talk. He welcomes Queen Noor; we are proud of her. Congratulations to His Majesty on his marriage and on the birth of his child. Second, in the brief time available to them, he hopes to explore as many common problems and opportunities as possible. We will present our analysis of what we face. He is eager to get his (the King’s) advice and counsel on our policy for the future. There is a large measure of identity in their common agreement. There is a minimum of differences within a common approach. His Majesty is welcome. Their meeting will be fruitful.

His Majesty thanked the President. He welcomes this opportunity to be in a country he respects, admires, and loves. He is one of the few leaders in his part of the world who feels an identity with the foundations of the United States, with its ideals and principles, which they hold dear in Jordan, as well. U.S. and Jordanian aims and objectives must always be the same; their objectives are very much one and the same—objectives of peace with dignity, and of stability. He is in a position to see and observe the Islamic world, which is now the focus of attention, brought about by its location, its sources of energy, and its potential for instability. This area must now be part of the free world; there is no other way to go. If there are divisions, or weaknesses, or cracks in cohesion, that should be overcome. Unfortunately, all of this is related to the Palestinian problem, and the fact that it is not yet totally resolved in a way that future generations can live with. He remembers his meetings with the President, through their meeting in Tehran. He knows that the President has given him more time than any other president. In their discussions on the Middle East, he can see that the President has greater sincerity on this problem and on resolving it than he has ever experienced before. Unfortunately, their hearts had moved away (from one another)—but not from the objective of peace. We (Jordanians) are always committed to it; it is dear to us; and we will try to contribute to it—to see it realized in any way we can. He remembers discussing with the President approaches to a comprehensive settlement—pre-Geneva, joint delegations, Palestinian involvement, etc. But events took a different course! Unfortunately, there was a lack of communication between him and the President; and both were “surprised” by events. There were gaps of time, understanding, cooperation—which he had always valued. He is very grateful to see the President, to talk, and to hear the President’s opinions on all matters. He will speak honestly and frankly on all of them. The area is one of danger. Conditions have changed since they met in Tehran—Iran, Afghanistan, and the changing attitudes of people in the area. He once thought that Jordan was on the front line, with dangers to Arab identity and the future. Others now face this as well. There is a history of struggle, going back hundreds, even thousands of years. Their future is in jeopardy. He will see what they can do in the area, to bring the countries closer together to face the challenge. The President looks clearly into the future, about our joint action to meet the threat, to our joint cause, and to our common future. He (King Hussein) is also concerned about the Europeans. It is true that Jordan is small—in its people and location. For many years past, they have struggled and made achievements. This is not a matter of survival, but of wanting something better than survival for his people. They want something: the future, defense, in the identity of people. There are limits there, too. It is a great problem they all face; they are at the receiving end of threats, developments, and events. They need to be with friends, dealing with contingencies, and need to play the role they can, defending their future. In the area of the Arab world, it is interesting to discuss that—the different attitudes, the problems they face. It is obvious that the Palestinian problem needs to be moved toward a solution. In particular, there needs to be a major role for the U.S., without which nothing will happen. What seems to be a step forward (note: Camp David) may be so in reality. But what is next? What about the real problems—Palestine, the difficult problems that need help and attention to be overcome. In all fields, our future cooperation is needed, in many fields. What can we do? Thank you very much for the opportunity to deal with you (the President). He (King Hussein) is ready to discuss with friends the President’s interests.

The President expressed his admiration for King Hussein, and for what he has done and tried to do in gaining a comprehensive peace. Also there is the history of His Majesty’s family—including his father and grandfather—in their courageous efforts to bring about the resolution of difficult issues. The President also complimented the courage of His Majesty and of his people, in preserving Jordan’s independence, integrity, and supporting human rights. He admires Jordan’s economic development, under His Majesty’s wise administration. We have a conglomeration of challenges in the region, beginning with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, with close to 100,000 troops there. The Soviets are trying to subjugate a courageous and free people. This is of deep concern to us. We are resolutely against the invasion. We are encouraging our Allies to take a position of clear, tangible, and permanent opposition to this occupation. We are more resolute than some others. Some of the Europeans are timid, vulnerable, and dependent on foreign trade. We are trying to get them to stand with us, and with the Moslem world, to convince the Soviets that they have nothing to gain and lots to lose through the continued occupation of Afghanistan. He has seen and admired the combined efforts of the Moslem leaders, which sent a signal to the Soviets. We will not abandon our effort to get the Soviets out, to enable the Afghan people to choose their own government, and to keep the country non-aligned.

The changes in Iran caused us great concern. Some elements of the revolution only want the right to choose their own government; but the irresponsibility of seizing the hostages shocked the United States, and is his greatest problem. We want Iran to be united, independent, and secure. We will not interfere—and this is a deep commitment. The Shah had been a friend of the U.S. and we had tried to work with him. But we have no animosity to the new leaders. We hope that Iran eventually will see the wisdom in releasing the hostages, so that we can have normal relations. Iran’s greatest threat is from the North. He appreciates His Majesty’s advice and help with the hostage situation. He hopes that the world will not forget the plight of the hostages. This was an act of international terrorism, the first time that a government had endorsed and supported such an action. It is abhorrent. The UN and the ICJ have acted, as well.

On the U.S. presence in the region—with its energy, the potentially explosive role of religious belief, social change, and struggles for influence—we see the region as vital to the whole world, perhaps more than any other. It is not a secret that we have some military presence there. We are not basing troops, but will be using facilities—in Somalia, Kenya, and Oman. This will be transient; and they are not bases. Some of the states welcome this. We have a large naval presence in the Indian Ocean, to stabilize it; then we will reduce the force.

Under difficult circumstances, we departed from His Majesty’s ideas on resolving the Israeli-Arab conflict, by taking advantage of the opportunity to resolve the Sinai problem. We laid the groundwork for the Palestinian people to participate in determining their own future. This is not perfect. But we have made progress. As for the future, it is difficult to predict. There are major problems—there is no responsible person to negotiate for the Palestinians living in the West Bank and Gaza. We hoped at Camp David that this would happen, but it has not materialized. This has crippled the prospects for complete success. The issue was to induce Israel to withdraw from the Sinai, and to withdraw from the West Bank—keeping some outposts—as a way of helping to resolve the problems and to permit the Palestinian people to participate in determining their own future. Some people would be able to return to the West Bank. It is not easy to negotiate under Prime Minister Begin; but there has been progress. He (the President) is determined to continue. This is not incompatible with His Majesty’s ultimate goals for the West Bank. It is an interim solution. After the Self-Governing Authority is set up, then discussions will take place on the permanent status of the West Bank and Gaza. We support Resolution 242. There should be a withdrawal by Israel from the occupied territories and guarantees for Israel’s security. He would like His Majesty’s advice on how to go about finding a way to get the Palestinian people to be represented. There is an obstacle: Israel will not talk with the PLO as long as it says it wants to destroy Israel and will not accept 242 and Israel’s right to exist. If the PLO will do this, however, we will talk with it. Maybe there is something possible in the interim—perhaps some mayors: this would get us over a difficult time. If Israel and Egypt go on with the talks, and make progress, then we will continue, and resist efforts to subvert the process. We welcome efforts that would add to the peace process, and would not oppose the Europeans on that basis, or a Jordanian initiative, to build on the process. However, we would resist any modification that would cancel 242 or threaten Israel, or that tried to undo the Egyptian-Israeli achievement. He sees and appreciates His Majesty’s efforts to reach the same goals: the right of self-determination; a withdrawal of Israeli West Bank forces; and the control of terrorism (where His Majesty has done an admirable job).

He sees changes taking place in Iraq—he sees it to be more responsible and moderate than before. Syria is going the other way; and it is more allied with the Soviet Union than any other state in the area. He would like to hear how His Majesty would approach the future—this would be helpful to him (the President). Maybe they have a different view of Sadat. He sees that it took an act of courage to resolve the conflict with Israel. He can’t comment on Sadat’s consultations with His Majesty and the Saudis: maybe this was inadequate. We saw—and were surprised—on how fast the situation moved after Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem, and we tried to take advantage of it. He believes that the peace treaty will be implemented in its entirety. If it can be extended—on Jordanian or U.S. ideas—to allow the Palestinian people to participate in determining their own future, then ultimately there will be hope of success. In the last two years that has been a major step forward. The future is hard to predict; it is not easy to deal with the Israelis; it is not easy for His Majesty to deal with the Syrians, Iraqis, and Palestinians. His Majesty can help him (the President) with ideas and how to provide more stability in the Arabian Peninsula, with relations with the two Yemens and Saudi Arabia. Jordan’s beneficial role in the Persian Gulf region is important to Jordan and to us.

Tomorrow, he will tell His Majesty about our concerns at the forthcoming Venice summit, and will discuss other issues. He has tried to present with candor our concept of the problems, commitments and concerns—about Iran, Afghanistan, the Soviet Union, and the peace process. He doesn’t believe that U.S. and Jordanian ultimate views are different. He is not sure, however, of His Majesty’s view of self-determination: an independent state between Jordan and Israel would be a mistake; but His Majesty will have to judge this for himself.

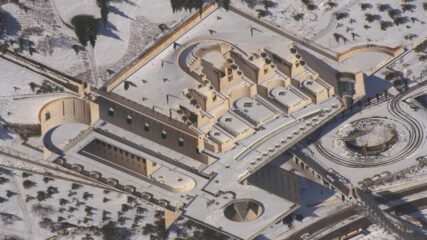

[Omitted here is discussion of the situation in Afghanistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and the Venice G–7 Economic Summit.] [Hussein:] On the Palestinian problem, Jordan was working on it, then there were surprises! (laughter) It is not a matter of consultations, and not a question of Sadat’s courage, as in his going to Jerusalem, etc. But it is a feeling he (His Majesty) developed over the years, that if there were a chance for peace, then they (the Arabs) should move together, and preserve cohesion between them to get Palestinian rights. Egypt has had a leading role in the area over the years; therefore Egypt has a moral responsibility to the rest of the Arabs. In 1967, Jordan went to war in support of Egypt, knowing what the result would be. This was done in response to an Arab league agreement. Jordan honored it—as did Syria. Since 1967, he (His Majesty) tried his best. He took a position on negotiating with Israel that was not against it. He tried to get his ideas and aims in all ways. He worked on Resolution 242 and helped to get Egypt’s support for it. He accepted Resolution 338. Jordan could not bargain over Palestinian rights. Was Israel willing to return the lands, either directly or under international auspices—with self-determination? If there is self-determination, he is sure the Palestinians will choose what we can live with. Most Palestinians are in Jordan. Most Palestinians carry Jordanian passports. The radicals do well only when hope appears closed. After many years—they only want to know the end of the process. The President was honest to say that he couldn’t say what that is. Jordan had to rely on his (the President’s) good will. But after so many promises and assurances, they couldn’t go into the unknown without knowing where the process was going.He does not want to divide Jerusalem. They say that there should be Arab sovereignty—sovereignty for the Christians and the Moslems in the Arab part of it. Let Jerusalem be a real city of peace. There should be self-determination for the rest (i.e. West Bank and Gaza). There should be an end to settlements. Jordan has prepared a slide show on the settlements, which he would be happy to show the President. This shows that all has changed; there are new obstacles. Maybe even stopping settlements now would not be enough. Water resources, the ecology—all have been changed. In Israel’s opinion, Jerusalem is Israeli; the West Bank is Israeli. There are rights for some, but they are under Israeli occupation. He has had a vivid impression that Israel wants the West Bank to be forgotten. Israel had the impression that it could remove Egypt from the scene. And this has happened. With the support and help they get, he doubts that they will change. But the Palestinians must be involved. Without Palestinian participation, there cannot be a real solution. If there is agreement otherwise, it will sow seeds of distrust, and then the radicals will get the opportunity to destroy the agreement. He is willing to do all he can for a real process, with an end in view—on the future of the Palestinians, and of Jordan, and of the region.

He is in touch with the PLO—that is a title: leaders change. Recently he has tried a little opening—he is not totally encircled. After Egypt moved (i.e. 1977), they faced a state where the area seemed to be disintegrating between left and right. An idea was floated and a meeting was held (i.e. in Baghdad); but friends (note: the United States) did not see what this meant. For the first time, all the rest of the Arab world spoke of 242 as the basis of a solution—including some extremists and the PLO. This held the Arabs together, and avoided disintegration which would have helped the enemies of the Arabs. This situation has changed recently. Syria is closer to the Soviet Union, and there are pressures in that country. Syria’s attitude tends to be negative on any solution—and this is more so, now. But they are part of a group—including Libya and Syria. Algeria has a decent president, who is honest and courageous, who will have an impact on his country—though he is not yet totally in control. For a time, Algeria will be part of this group. He hopes it will change.

He sees pressure on the PLO to encourage the radical elements and extremist attitudes. He has tried to open the door to the PLO, and show that they can come towards us; that they do not face only this pressure. The PLO approached Jordan to talk with Jordan’s friends to see what can be agreed on—for example, the future of Jordan and the Palestinians together, as in the early 1970s, while preserving their separate identities. He gets this from Arafat: the possibility is still there. And Sadat broke relations with Jordan when he (His Majesty) proposed this idea in 1972 (laughter)! So, something can be done there. Arafat said that he wanted to remove U.S. fears and Israeli excuses against moving to a just and durable peace. Arafat came to Jordan recently to see the Mayor of Nablus, and again spoke of his difficulties and pressures. His Majesty told Arafat of his coming here. The PLO is anxious to keep the dialogue going with Jordan. It tends to be closer to Jordan. He (His Majesty) promised to give what help he can in the interests of the Palestinians. The PLO has sent an envoy to the UN in New York now, if he (His Majesty) wants to convey anything.

Israel’s recognition of Palestinian rights, and Palestinians recognition of Israel’s right to exist have to come. But which should come first? It should be simultaneous. Jordan admires the Afghan people’s resistance. It is similar with the Palestinians. If there is a lack of progress toward a solution, there will be a movement towards violence. On the question of finding someone to speak for the Palestinians, he was ready—if Israel would go out of the territories and solve the Jerusalem question. If he can now get support for doing so, he will go back and say that this is what Washington sees as an end result. If they do not know the end results, it will be impossible to do anything, since it would serve no purpose. The mayors were elected under occupation. They are deeply concerned about the beginning of attempts to intimidate them into leaving. What will happen? He does not know. The President sees this even without Jordan’s daily contacts. The President is sincere; he has put in lots of time on the problem. But Jordan lives with it every day. If this were 1967, maybe the experience would be different. He has tried every door, without results.

The situation in Syria . . . Lebanon is a problem. It is unfortunate. He does not even know the issues any more. Israel and Syria are there (i.e. in Lebanon), but it is not a clear-cut issue. There are three groups of Christians; Sunni and Shia Moslems; the Syrians; the Palestinians. The nightmare continues, with suffering and danger. He does not know the result. But Lebanon is a time bomb. This does not serve Lebanese or others’ interests.

In Jordan, they are making progress. They are affected by oil price increases. Maybe the oil producers see their benefits going up; and the industrial nations suffer less than Jordan does. The majority of countries try to make progress and to catch up—they are suffering most from this instability (i.e. in oil markets). This is another area of danger. There is a danger of eruption of more radical regimes’ taking over in the world as such.

Jordan is in touch with its European friends. It senses their concern for the future. What will happen next? He believes that we are not [now?] at a critical juncture, where misunderstandings are the order of the day, and lack of communication. Are we (i.e. Jordan and the U.S.) partners in seeking a better future? Will we share the making of the future? How can we ensure that we work together? The Europeans are reluctant to move. Jordan does not want something that is an alternative to what has happened (i.e. Egypt-Israel peace treaty) or to block it. But what can we do about Jerusalem, the West Bank, Palestinian rights, and how can we relate to other parties? The Europeans are anxious to avoid a U.S. veto. This leads to the idea of differences in the Alliance at a difficult time.

We can wait to see what happens. He hopes to go home knowing the President’s ideas. But when that ends in disappointment, then he fears that hope will be lost, and only the extremists will benefit. In Jordan, they have problems. Jordan is close to the United States. Jordan is grateful for U.S. economic help—which has diminished—and he is not asking now. But the United States knows where Jordan stands. He wants to know: how did things go wrong (i.e. between Jordan and the U.S.)? How did it reach this point? Beyond that—if we are still partners—how can we reach common objectives?

The President said that this was extremely helpful. First, there is our friendship. The U.S. commitment to Jordan’s security and prosperity is solid and unchanging. He was disappointed by the lack of Jordanian support for Camp David. He has a great deal of investment in it, and saw it as the only viable way to get goals that both he and His Majesty share. It has one defect, which can be corrected: the need to have a firm, recognizable voice of the Palestinians, making their demands on water, total withdrawal, land, a share in security, an end to settlement, and resolution of Jerusalem. No one does this now—with world attention and approval—negotiating with Israel, the U.S., and Egypt to get His Majesty’s goals. Therefore it is very difficult for us when others say that this avenue should not be pursued and that there is a better one—such as the U.N., or Geneva, where both the PLO and Israel would be represented. We went down that road. But the Arab nations could not agree on how to negotiate, or on the role of the PLO and the Palestinians. We tried it, with determination, and even got a U.S.-Soviet agreement. But we couldn’t get Syrian or PLO agreement. The alternative was a surprise, but he was grateful for it: Sadat broke the log-jam.

If there is a desire to resolve the issues, and to capture world attention, to get support and to prevail over Israeli obstructionism, isn’t the best way to get someone among the Palestinian Arabs to join the negotiations, with the tacit support of the PLO and Jordan? His Majesty says he cannot negotiate for the Palestinians, but will he support others—for example, some mayors—if they adhere to their principles—such as total withdrawal and Jerusalem? Now there is a vacuum; it is difficult for Egypt to speak for the Palestinians.

He (the President) is convinced that most Israelis want peace, and will go a long way towards self-determination and withdrawal—except from Jerusalem. At Camp David, they had a paragraph on Jerusalem that was satisfactory to Israel and to Egyptians who were even closer to the Palestinians than Sadat. Israel found it difficult to withdraw from the Sinai, to give up the oil, and abandon its strategic position at Sharm-el-Sheikh. It was torture for Begin to have settlers come out of the Sinai. This was very difficult, but he did it. The reason was that the Israeli people want a permanent peace that would make them secure. Israelis still have that feeling. Begin is not popular. He represents the majority on some issues—for example, the Israelis are terrified about a divided Jerusalem, under which they could not go to the Western Wall, as when Jordan occupied Jerusalem. Therefore we do not see the advisability of abandoning Camp David. Another process would be neither rapid or lead to a peaceful settlement. Jordan and the PLO are not in the talks. If you would get Palestinians to join, then Israel would be under difficult negotiating circumstances and it would arouse in the world a belief that there is a desire of Jordan and the Palestinians to resolve the issues. He (the President) has no desire to support Israeli positions against the Arab world. Sadat will tell His Majesty that. There is a U.S. and Egyptian position together. He (the President) would be happy to see Israel out of the West Bank and Gaza, with full autonomy and preparations for its final status. He would be pleased to see a total West Bank confederation with Jordan and see the Palestinians support it. This is what he wants. Many Israelis want it, as well, except for “total” withdrawal—they want some minor modifications. There is a stalemate now, though we are trying to make progress. His Majesty should see our determination. There is terrorism on both sides; and we deplore both.

In summary, to underline His Majesty’s commitment, is there some way to pursue the process of Camp David, without Jordan or the PLO in? This brings him to the conclusion that if Palestinian representatives were in for the next few months, and we see nothing happen, then we will explore something different—though always within 242.

Perhaps it was a mistake to go so far with Camp David without Jordan. We understand that Sadat after Camp David was to go to Morocco to see you (His Majesty). Later, we got your list of questions and responded to them. If we made a mistake, it was not deliberate. He (the President) believes that without some other process, this (i.e. Camp David) is the best. It is not perfect, but it is the best alternative.

One last thing, concerning the PLO: when he has met with Assad, His Majesty, and the Saudis—including Fahd—and Sadat, he has always asked that they induce Arafat to endorse 242 and Israel’s right to exist. Following that—or concurrently—we would deal with the PLO to look for a solution. This has not proved possible through private encouragement—Arafat talks about this as his bargaining chip—and is an element of the problem we have not been able to solve. Our commitment to Israel’s security is complete. Israel does not ask for U.S. forces; we provide its security needs. Maybe there is an incompatibility in our hopes to resolve the problem. Does His Majesty see what is possible to do?

King Hussein said that they can see when they are at home, with the PLO, what can be done.

The President said that he expects that getting Palestinians into the talks would be hard. But negotiations and communications are important. He had been surprised how far Israel had moved on the Egyptian front, and on its commitment to principles on withdrawal, etc. He cannot predict success, but he has seen movement before.

King Hussein said that it is precisely 242. Perhaps we can look at it later. That was adopted after the 1967 war and only talked about countries. The Palestinians objected: 242 did not talk about their rights.

The President said that 242 just mentioned refugees.

King Hussein said that it was the missing ingredient. The President said that with the Saudis, we drafted a statement the PLO could issue, putting forward its reservations on full Palestinian rights. He presumes that Arafat saw it, but it didn’t work.

King Hussein said that at that point Begin arrived (laughter)!

The President said that Begin went further on Sinai than the Labor Government. But he is more extreme about the West Bank.

The Prime Minister agreed.

The President said that Labor, whether under Meir or Rabin, had not been prepared to withdraw from Sinai or give up Sharm-el-Sheikh, etc. Begin has done some difficult things, and went against his political allies.

King Hussein agreed.

The Prime Minister said that it was hard now with the West Bank.

The President said he understood.

King Hussein said that he understood the President’s disappointment on Camp David concerning Jordan’s not supporting it. He had sent the President a letter then; and sent an identical letter to Sadat.

The Prime Minister said that Sadat wrote to His Majesty from Camp David.

The President said that Sadat had told him so.

King Hussein said that Sadat wrote that he was adhering to the same line and to all the points he (Sadat) had made in the Knesset. Jordan had agreed about them.

The Prime Minister said that did not include separating the process into two parts. It was a shock, therefore, when Sadat did so at Camp David and backed off on self-determination.

The President said that from Sadat’s and his perspective, he (Sadat) did not abandon this in a separate agreement. He (Sadat) did not give up self-determination or the return of Jerusalem. He (Sadat) did not abandon it. Rather they went round it, and said that the agreement would be an interim one, to provide later negotiations on the final status, including Palestinian rights. This is the difference between His Majesty on the one hand and Sadat and himself on the other.

The Prime Minister said that His Majesty is under the impression that the Israeli strategy has been to isolate Egypt, and they practically said to His Majesty that they wanted to solve the Egyptian problem and then Israel would absorb the West Bank.

The President said he doesn’t doubt that goal. Israel prefers to keep the West Bank, Gaza, and Sinai, but at the root wants peace. Many Israelis see that, if they insist on keeping the West Bank, they will not have a permanent peace. At Camp David, it was agreed that Palestinians could join the talks in the Jordanian delegation, and others could be brought in as mutually agreed. People from the West Bank and Gaza could come in as part of the Jordanian and Egyptian delegations. This still has promise. If Jordan is not in the talks—and he wished they would be—there should be another way.

The Prime Minister said that they had dealt with the Israelis for a long time.

The President said that he had read about it in the newspapers (laughter)!

King Hussein said that that had been a violation of the only agreement between Jordan and Israel (laughter)!

The Prime Minister said that Israeli actions are to absorb the West Bank—on the ground. Without a commitment that the result of the process is self-determination, Jordan couldn’t join the talks. Jordan would be used as an umbrella while Israel absorbed the West Bank through settlements—in the Arab view. This was the dilemma after Camp David. This was the fear they tried to convey before Camp David, that Jordan would look like the obstruction, whereas Jordan is trying to provide the basis for a viable settlement.

King Hussein said that there is a basis for future misunderstanding. There are two schools of thought in the Arab world. Some say that there should be concentration on the remaining problems. Others like to undermine Camp David and return to the past. This camp is more aligned with the extremists. Security should be for all; Jordan wants assurances for itself, too. All right, they will think about it (i.e. what the President had said on Palestinian involvement).

The President said he hopes His Majesty will think about it. He sees differences between the Jordanian position and ours; they are important.

The Prime Minister said that they were not fundamental.

The President agreed. The most difficult issue is Jerusalem. As Begin says, its ultimate status should be resolved in negotiations. Second, there is the end of Israeli occupation and military government, which Dayan and Weizman support. The definition of full autonomy needs to be hammered out. How much Israel should get out is to be negotiated. The Labor Party is for partition. Begin says that the Palestinians should be left to manage their own affairs. He (the President) is for full autonomy. Begin is for full autonomy. Some difference! (laughter)! We need to find a means for the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, with PLO support, to get in the talks—as long as we make progress. They can make strong demands, and Egypt will support them. If the process still breaks down, then all of us will look for alternatives. We will do our best now. He fears that otherwise the situation will get worse. There will be deterioration.

He feels much better after their talk. He regrets there has not been more communication.

The Prime Minister said that this was a good occasion.

The President said that, to be candid, he had felt that Jordan had led public condemnation of Camp David, even more than Iraq and Syria. He had had a grievance. Maybe he had expected too much; or assumed at Camp David to speak for Jordan. He (the President) has no criticism left; he understands better now. He had been grieved.

The Prime Minister said that that represented exaggerated reporting.

King Hussein said that they, too, have press problems (laughter)!

The Prime Minister said that, since Camp David, Jordan had worked on alternative routes, but had not denounced the United States or Camp David. The media in the West, and in the United States, were more influenced towards Israel. Jordan’s position was shown in a negative light, whereas they thought they were being positive. At Baghdad, they had tried to get a resolution that was not extreme.

The President said that was accurate: the negative aspects were emphasized.

The Prime Minister said that Begin and Sadat had distorted Jordan’s position.

The President joked that he couldn’t imagine that happening (laughter)!

(The meeting concluded at 12:22 p.m.)