David Ben-Gurion, “Vision and Redemption,” 1958. Reprinted in Zionist Background Papers, The Land of Israel in Jewish History, American Zionist Youth Foundation, New York, 1969.

Note: In addition to being Israel’s first prime minister and a significant leader in the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine or Eretz Yisrael before the state’s establishment, David Ben-Gurion was above all a Zionist enthusiast, expressed through prolific writings. He also kept detailed diaries of events, wrote books, letters and articles, and gave hundreds of speeches about the Jewish people, Zionism and Israel. He was as much a Jewish historian as he was an effective political leader. He was uncompromising in his drive to make and sustain the Jewish state, finding its contemporary justification in the biblical and Jewish past. He was Zionism’s most articulate voice for Israel as part of Jewish continuity. What follows is an abbreviated version of one of the many deep, lengthy and nationalistically conscious presentations Ben-Gurion made. It was presented and written in 1958 as “Vision and Redemption” and was reprinted in Zionist Background Papers: The Land of Israel in Jewish History, American Zionist Youth Foundation, New York, 1969.

Redemption

We are now in the tenth year after the renewal of the Jewish State in our ancient homeland. In our days we have seen a number of nations that have emerged from bondage to freedom, in Europe, Asia and Africa. India, Burma, Ceylon and other countries gained their independence almost simultaneously with the State of Israel. But everyone knows the fundamental difference between the rise of Israel and that of those countries. The nations of India, Burma and Ceylon lived on their own territories all the time; but at certain periods they fell under the domination of foreign conquerors, and when they cast off foreign rule, they were left independent. Not so with Israel. Nor does the rise of Israel resemble the rise of the United States, Canada, Australia, or the Latin American countries.

These countries were rediscovered by conquering voyagers from Spain, Portugal and Britain. The metropolis in Europe sent them emigrants whom they settled, and after the settlers had arrived at a certain degree of development, they split off from the metropolis by force or by agreement, and took over command of their own affairs. The rise of Israel, like the survival of Israel in exile, is a unique phenomenon in world history, and it can shed light on the riddle of the survival of Israel in exile.

The Jewish state was revived in a period when the House of Israel in the Diaspora was not as wholehearted and united as it was two hundred years ago in its faith; neither in the observance of the laws and commandments nor in the “religious idea”, in which Professor Kaufmann sees the secret of the survival of Judaism. There is no doubt, however, that without the forces which preserved Judaism in the Diaspora we would not have achieved the revival of Israel. It was not a conquering and settling power, nor an enslaved nation in its own land casting off the foreign yoke, that revived Israel. In the beginning of our revival was the vision.

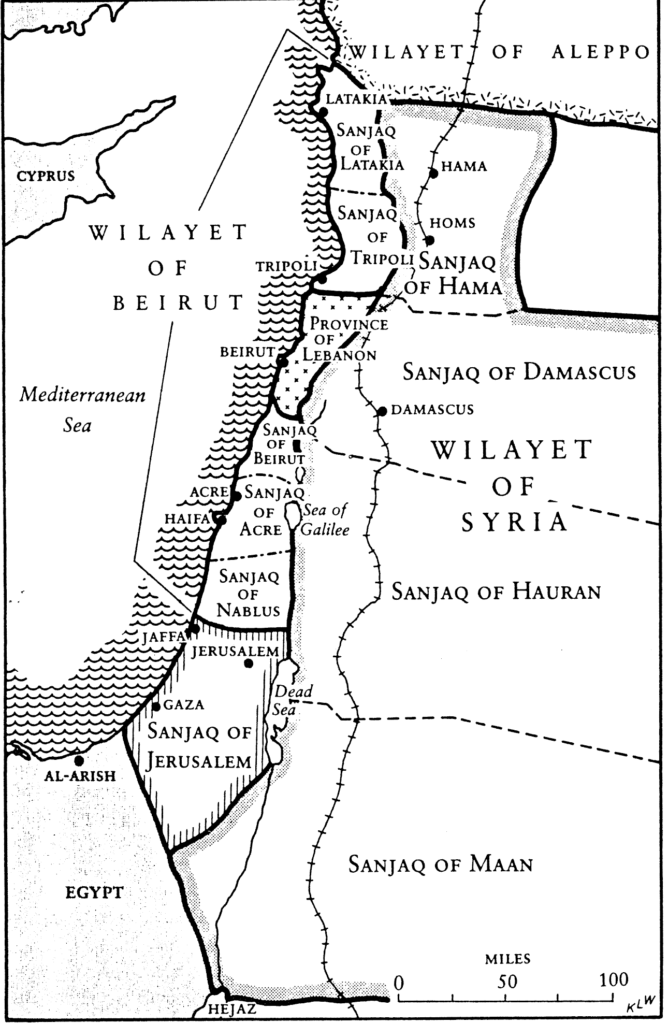

The State of Israel was established in a country which had been inhabited by Arabs for 1,400 years, and it is surrounded on the South, the East and the North by Arab countries. The land of Israel itself was ruined and impoverished and the standard of living in it was lower than that of the countries from which the Jews who began to rebuild it came. As late as 1918, at the end of the First World War, there were fewer than, 60,000 Jews in this country, i.e. less than 10 percent of its non-Jewish inhabitants. And yet in this land there has arisen in our days the Jewish state.

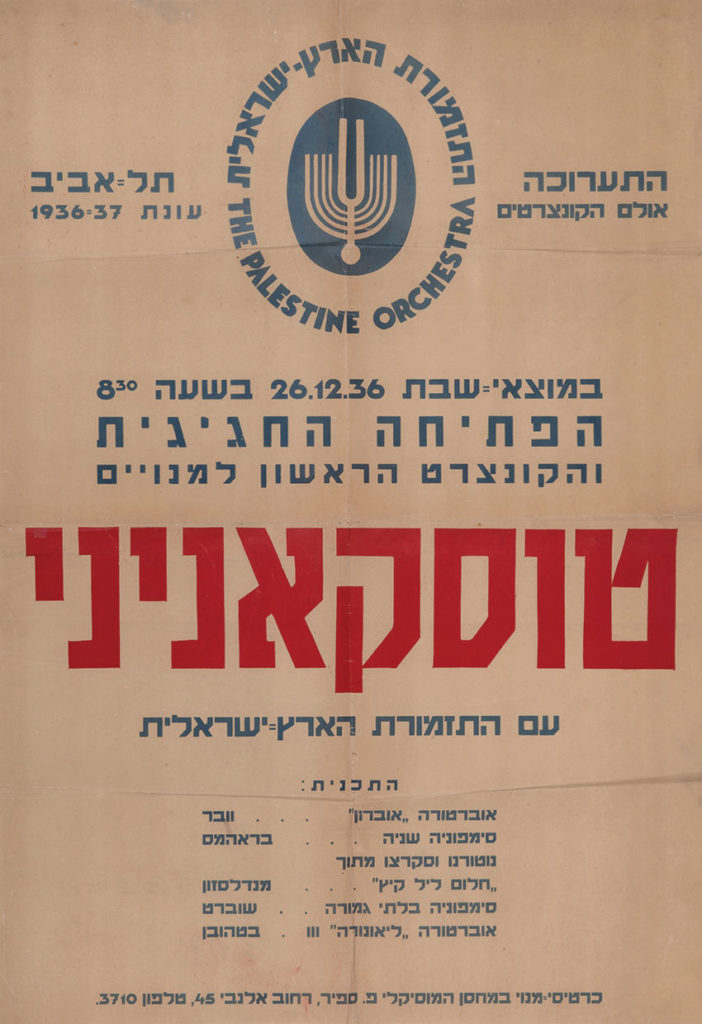

The second thing that has happened is also unique: the Hebrew language, which the people appeared to have laid aside for two thousand years, came to life again, and became the language of speech, life and literature, and of the revived State of Israel. Nothing like this has ever happened in the history of languages.

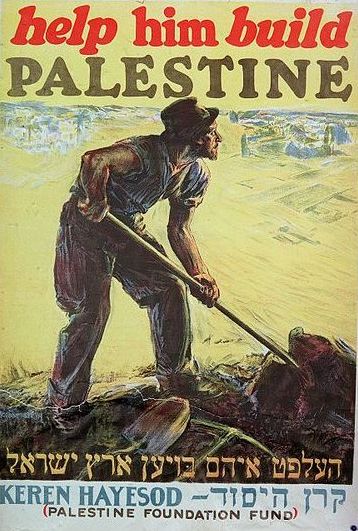

Still a third thing has happened in Israel: in this country the Jews have fundamentally transformed their economic way of life and taken up manual labor and the tilling of the soil. What, therefore, is the explanation of this extraordinary political and cultural phenomenon, which has no parallel in human history?

The Messianic vision of redemption, the profound spiritual attachment to Israel’s ancient homeland and to the Hebrew language, in which the Book of Books is written, were the deep and never-failing springs from which the scattered sons of Israel in the Diaspora drew from hundreds of years the moral and spiritual strength to resist all the difficulties of exile and to survive until the coming of national redemption. In the Messianic vision of redemption an organic bond was woven between Jewish national redemption and general human redemption.

In order to understand the function of the State in Jewish history from now onwards, it is necessary to discuss the further changes which radically altered the nature of the Jewish people in the first half of the present century, before the rise of the State.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were ten and a half million Jews in the world. More than 80 percent of them (8,673,000) were concentrated in Europe, and less than 10 percent lived on the American continent: about one million in the United States, and about 50,000 in the other countries of the New World. At that time about 700,000 Jews lived in Asia and Africa, and about 55,000 in the Land of Israel. Before the beginning of the Second World War, the Jewish people numbered about 16,500,000, and although in the meantime millions had emigrated overseas, the great majority of the Jewish people, almost nine million souls, lived in Europe.

European Jewry, especially that of Eastern Europe, had been for the previous three centuries the Mother of Jewry: it housed the centers of learning; within it there arose the Emancipation movement; in it there was born the Haskala and Modern Hebrew and Yiddish literatures. In its midst Judische Wissenschaft flourished, from it there grew the Hibbat Zion movement and the Jewish workers movement, and when the First Zionist Congress was convened at the end of the nineteenth century by the creator of political Zionism, Dr. Theodor Herzl, European Jewry was the major part, the fortress and support, of the Zionist movement.

In the Zionist movement we must distinguish between ancient sources, almost as ancient as the Jewish people itself and new circumstances and factors which grew on the soil of the modern era in Europe in the nineteenth century and in the beginning of the twentieth. These ancient sources are the profound spiritual attachment to the ancient homeland and the Messianic hope.

The sporadic waves of immigration from various countries, the visits of emissaries from Palestine to the various parts of the Diaspora, the Messianic movements that arose from time to time, from the period following the destruction of the Temple to the eighteenth century -all these were a real and living expression of the attachment and the longing for the homeland, and the hopes that throbbed in the hearts of the people for national redemption and salvation. Until the beginning of the emancipation in the nineteenth century, all Jews wherever they were, knew that the places where they lived were only a temporary exile, and it did not even occur to them that they were a part of the peoples among whom they lived, just as such an idea was foreign to those people themselves. This feeling of being foreign existed in East European Jewry till the last moment. The Jewries of Russia, Poland, Rumania and the Balkans knew all the time that they were a minority people in a foreign land, and in the eighties of the nineteenth century there began a mass “migration from the countries of the East to lands overseas.

The Modern Movement of Redemption

Only in the last quarter of the nineteenth century did the pioneering spark flame up and grow and incessantly gather strength, until it arose like a pillar of fire lighting the way for the loyal sons of the Jewish people in all parts of the Diaspora to the establishment of the Jewish State.

Without the guidance of a social ideal, which ‘was also born in the nineteenth century, the pioneering impetus would have lost its way and wasted its efforts, and the Jewish state would not have been established: this was the idea that labor is the principal foundation for a healthy national life. Not only did the Jews in the Diaspora live in exile and depend on the decisions of others, but the structure of their economic and social life as different from that of any independent people living in its own land and controlling its destiny. The Jews were landless and were not employed in the principal branches of the economy on which the self-supporting existence of a nation depends. Without a mass return to the soil and to labor, without the transformation of the economic and social structure of the Jewish population in the Land of Israel, we would never have arrived at a Jewish State. It is impossible to conceive of a state the majority of whose people does not work the soil and carry out the types of work required for its economic survival.

The feeling of foreignness, either as a reaction to anti-Semitism in central and western Europe, or as the outcome of the consciousness of a specific Jewish character and the absence of a traditional bond with the gentile nation and its culture, as in Eastern Europe; the example of the national and social liberation movements; and the recognition of the value of labor as the main basis for national life all these were, common to large parts of European Jewry, and almost only of European Jewry. It was there that there appeared the pioneering movement which transformed the aspiration of generations into an act of daily implementation; it was this movement that laid the foundations for the Jewish State, the most wonderful event in the life of the Jewish people since the conquests of Joshua, son of Nun.

But during the twenty-eight years between the end of the First World War and the end of World War II, European Jewry was visited by two appalling disasters: one-third of East European Jewry was cut off from World Jewry by force about forty years ago, at the end of the First World War, by the Bolshevik regime in Russia; and about two-thirds were slaughtered by the Nazi butchers during the Second World War.

This was a double disaster, unparalleled even in the history of our people, which visited us in the first half of this century, before the establishment of the State. Only scanty fragments of European Jewry were left in freedom, and the period of European Jewry in the life of the Jewish people came to an end, never to return. In the second half of this century, however, there was a second change, a fruitful and beneficial one, in the growth of the great Jewish center in the United States of America, from one million at the beginning of the century to over five millions in our own day.

And this was not only a quantitative growth. In the foremost country of the New World there grew a Jewish center, the like of which was never seen in the Diaspora for wealth, influence and power, for political and spiritual capacity. And this Jewry, which had first considered itself a spiritual ‘colony’ of European Jewry, has become in our own day the political, material and cultural metropolis of Diaspora Jewry. Here there arose a great labor movement, though it is now shrinking as the second and third generations of the immigrants go over to trade and industry and the free professions. Here there arose important centers of Jewish scholarship, Jewish universities and academies for teachers and rabbis; here the feeling of exile and foreignness grew weaker and disappeared completely, and although the ideology of assimilation struck no roots in American Jewry, assimilation in practice -in language, culture, manners, economy and political life -is constantly growing. The Jews of America, including the Zionists among them, see themselves as a part of the American people, while at the same time they consider themselves a Jewish community; their hearts are alert to every Jewish cause, and their material and political assistance for the building of the Yishuv and the establishment of the State has been of inestimable value.

When the Jewish State arose in the middle of 1948, the character, status, distribution and conditions of life of the Jewish people were completely different from what they were at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century,

The State — A New Chapter

The rise of Israel opened up a new chapter not only in the history of this country but in the history of Jewry as a whole. It straightened the back of every Jew wherever he lived; in the course of a few years it redeemed hundreds of thousands of Jews from poverty and degeneration in exile, and transformed them into proud, creative Jews, the builders and defenders of their country; it poured new hope into the hearts of the helpless and muzzled Jews of the Soviet bloc; it revealed the extraordinary capacity of Jews for accomplishment in all spheres of human creative work; it revived Jewish heroism; it assured every Jew who enjoys freedom of movement in the land where he lives, of the opportunity to live in his independent homeland if he chooses to do so, thus ensuring potentially, if not in practice, a life of independence for the entire Jewish people.

On the international scene there appeared a free Jewish nation, equal in rights with the rest of the family of nations. It is not remarkable that all parts of the Jewish people in the Diaspora, whether they called themselves’ Zionists or non-Zionists, orthodox or non-religious, whether they lived in lands of prosperity and freedom or in lands of poverty and enslavement, welcomed the rise of the State with love and pride, and the State became the central pillar on which the unity of Diaspora Jewry now rests. Let us not, however, be overconfident; the vision of redemption brought forth the State, but the State is still far from the realization of the vision.

The State has solved a number of problems, and also produced new ones, Jewish sovereignty enables the Jew in Israel to mould his own life as he wishes, according to his own needs and values, in loyalty solely to his own spirit, his historic heritage, his vision of the future, In Israel, the barrier between the Jew and the human has fallen, The Jews in their own state are no longer subject to two opposing and conflicting authorities: on the one hand to the authority of the gentile people in all economic, political and social matters and in most spiritual and cultural questions, as citizens and subjects of a state with a non-Jewish (or even anti-Jewish) majority; and on the other hand, their own authority in the one small and poor corner which draws its sustenance only from the past, in which they function as members of the Mosaic faith or of the Jewish people in the world.

Israel has restored to the people living in its midst their wholeness as Jews and human beings; the sovereign Jewish authority covers all the needs, acts and aspirations of man in Israel. In Israel, the profound cleavage, which in the Diaspora split, and still splits, the lives and souls of Jews, has been healed -the cleavage which impoverished both the man in the Jew and the Jew in the man. Our lives have again become, as in the days of the Bible, a complete unity of existence and experience, which embraces in a Jewish framework all the contents of the life of man and people, all his acts, needs, aspirations, cares, problems and hopes.

Only here, where we have become free citizens in the State of Israel, have we become citizens of the world with equal rights, who must adopt an attitude of our own on all the problems of the world and the relations between nations. This sovereignty also imposes on us heave responsibilities which were unknown to Jews in the world for many centuries: we bear the full responsibility for our fate and our future, and we have a heavy price to pay for this responsibility.

The State’s Two Supreme Laws

This state has been established by the strength of the entire Jewish people, and not only that of the Jewish people who live in our own generation; I have no doubt that all generations of Jewry have a share in the extraordinary and tremendous accomplishment of our day: the state has been established for the entire Jewish people. But in practice, the state is today inhabited by only 1,700,000 Jews, about 14 percent of the Jewish people. For this reason alone, the State considers itself no more than a beginning. The state of Israel has two central objectives that were laid down in the Proclamation of Independence and in two special laws, which- although they are not called basic laws- and I consider to be the supreme laws of the State of Israel, destined to be a light for the generations. Until these are fully implemented the work of the State of Israel will not be completed.

The first is the Law of the Return, which contains the objective of the ingathering of the exiles. This law decrees that it is not the State who grant the Jew the right to settle in Israel, but that it this is his right by reason of the fact that he is a Jew, if only he wishes to join the population of the country. In Israel a Jewish citizen has no privileges over the non-Jewish citizen. In the Proclamation of Independence we laid it down that “The State of Israel will uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of religion, race or sex, ” but the State sees the right of Jews to return to the Land of Israel as preceding its foundation, and having its source in the historic and never-broken bond between the Jews and their ancient homeland. The law of the Return is not like those immigration laws existing in other countries which lay down the conditions under which the state receives immigration from abroad. The law of the Return is the law of the historic permanence and continuity of the bond between the land and our people; it lays down the principle of state by virtue of which the State of Israel has been revived.

The two forces which were active in the process of aliya before the rise of the State -distress and the vision of redemption -have now been reinforced by the attractive power of Israel, its freedom and independence, and its creative momentum. Only the future will show what parts of our people will return to the homeland, but we are certain that the millions of Jews who long to come to Israel, and who for decades have been deprived of the right to do so, will surely come in the end.

The second law determines the social direction of the State and the character to which we aspire for the People of Israel -and it is contained in the State Education Law. Paragraph two of this Law says: “The object of State education is to base elementary education in the State on the values of Israel and the achievements of science; on the love of the homeland and devotion to the State of Israel and the Jewish people; on training in agricultural labor and handicraft; on pioneering implementation, on striving for a society built on freedom, equality, tolerance, mutual assistance and love of humanity.” This law lays down the main lines for making us into a model people and a model state, and asserts our unfailing bond with the Jewish people in the world.

Our historic goal is a Jew society built on freedom, equality, tolerance, mutual assistance and love of humanity, in other words, a society without exploitation, discrimination, enslavement, the rule of man over man, the violation of conscience and tyranny. This law also expresses our aspiration to develop in Israel a culture built on the values of Judaism and the achievements of science. And the Law demands devotion not only to the State but also to the Jewish people.

Both this Law and the Law of the Return are far from a state of complete realization; they are only signposts by which the State wishes, and is bound, to be guided, so that it may survive and achieve its historic aim.

We cannot boast that the people of Israel are today a model people, although within our short period of independence we have perhaps made more progress relatively than any other country in a similar period. Our society is far from perfect, and it needs reforms. Nor can we congratulate ourselves that by adding a million Jews to our population after the rise of the State we have carried out the ingathering of the exiles. But I shall try briefly to describe both the historic necessity of making this country into a model state, and the qualifications we have to carry out such a great ideal, as well as the need and the prospects for the ingathering of the exiles to the maximum extent.

Israel’s Faithful Ally

Israel has one faithful ally in the world: the Jewish people. Israel is the only country in the world which has no “relatives” from the point of view of religion, language, origin or culture, such as are possessed by the Scandinavian peoples, the English-speaking peoples, the Arab peoples, the Catholic peoples, the Buddhist peoples, etc. We are a people that lives alone. Our nearest neighbors, both from the geographical point of view and from the point of view of race and language, are our bitterest enemies and I am afraid they will not speedily be reconciled to our existence and our growth.

The only loyal ally we have is the Jewish people. There is no doubt that no considerable parts of scattered Jewry will join us in the near future: both Jews from the Islamic countries and Jews from Europe, as well as no small number from the Jewries of the prosperous countries. But there was a Jewish Diaspora as early as in the days of the First Temple, which preceded the Babylonian exile; this Diaspora was in Egypt. During the period of the Second Temple the Diaspora grew, and it is hard to imagine that the Third Commonwealth will absorb the whole of the Diaspora of our days. The survival of Jewry from now on is inconceivable without the State of Israel and an inner attachment to the State. But the survival of the State is also inconceivable without a loyal partnership between it and all the Jewries of the Diaspora. Without a moral, cultural and political illumination that will go out from Israel to all parts of the Diaspora, this partnership may be undermined. The War of Independence and the’ Sinai Campaign aroused Jewish pride and raised the status of Jews among the Jewish people and in the whole world. But the State of Israel was not created to be a Jewish Sparta, and it is not by military heroism that it will win the admiration of the Jewish people.

Only by being a model nation, of which every Jew, wherever he is, can be proud, shall we preserve the love of the Jewish people and its loyalty to Israel. Our status in the world, too, will not be determined by our material wealth or by our military heroism, but by the radiance of our achievements, our culture and our society -and only by virtue of these will we acquire the friendship of the nations. And although there is no lack of shadows -most of them heavy in our lives today, we have sufficient grounds for the faith that we have it in our power to be a model people.

And it is already possible to point to three elements in Israel today which give clear indications of the moral and intellectual capacities latent within us; they are the labor settlements, the Israel Defense Forces, and our men of science, research, literature and art, who can bear comparison in their relative quantity and high quality with those of any other people in the world.

The labor settlements have marked new road towards a society built on liberty, equality and mutual assistance, which have no parallel in any country, in the East or the West. The Israel Defense Forces are not only a loyal and effective instrument for defense, but an educational framework that raises human standards, breaks down communal barriers, and gives the youth of Israel self-confidence, responsibility to the community, and a vision for the future.

And although in the few years of our sovereign independence we have been compelled to invest tremendous resources in defense, the absorption of immigrants and the building of our economy, and we shall have to continue to do so for many years to come, we have succeeded in establishing institutions of science and research and development, literature and art, on a level as high as that of the most developed countries.

The Diaspora of Today

We are now faced with a Jewish Diaspora which is radically different from that which existed fifty years ago. The two largest and most important centers of Jewry ill the Diaspora are in the United States and the Soviet Union. The greater part of the Jewry of the Moslem countries has already come to Israel, and it may be assumed that most of the remainder will also come here within the next few years. American Jewry is different from any Jewish community we have known so far in our history, from Babylon Jewry in ancient times to Russian Jewry in the days of the Tsars. It has grown up in freedom and equality, and all those among whom American Jews live are descendants of immigrants like themselves. In one thing alone does it resemble all the other Jewish communities in the Diaspora: its economic and social structure is different from that of the majority of American people? The Jews of America belong more and more to the middle and upper classes; the number of farmers is almost nil and the number of workers is constantly declining. Jews are being absorbed in trade, industry and the free professions, and they are making great material progress in these vocations. How this will influence their situation and the attitude of the majority to them, time alone will tell.

In all other respects there is no difference between Jews and non-Jews. There is no ideology of assimilation among the American Jews, but there has been an increase in assimilation in practice, although this assimilation does not involve the denial of Jewishness. This Jewishness, however, has few and feeble foundations. There is an increase in religious worship, but it is doubtful whether it involves an intensification of religious consciousness. Membership in a synagogue or a temple is not identical with an attachment to traditional law or to the spiritual values of the prophets of Israel. Members of the bodies that belong to the Zionist Organization are no different from those Jews who do not belong to that Organization.

Zionism in America is not based on the consciousness of exile and foreignness, and on the will and the need to turn to Zion. Any comparison between the fate of European Jewry and that of Jewry in the United States whether for good or for ill is baseless. There is nothing to prevent the Jews in America preserving their Jewishness and their bond with Zion, but at the same time there is no internal or external obligation to do so. Any scientific prognosis based on historical necessity -if scientific prognoses are possible at all in history -is liable to be disproved. There is no particular usefulness in abstract discussions of the future of Jewry in America -but we should discuss what is to be done to safeguard its future in accordance with our Jewish aspirations and needs.

The position of Jewry in the Soviet bloc, and especially in the Soviet Union, is different. This Jewry has been condemned to disintegration for about forty years by a hostile, totalitarian regime. The generation that has grown up under Bolshevik rule cannot receive any Jewish education, and it has been forcibly severed from its historical tradition and its bonds with the Jewish people and the Land of Israel. It cannot read and write either Hebrew or Yiddish. It is forbidden to leave Russia. And had it not been for the rise of Israel, it would have been condemned sooner or later to disappearance in the Jewish sense.

But even a totalitarian regime is neither all-powerful, nor safe against changes and fluctuations. In contradiction to the declared theory of self-determination for all the peoples in the Soviet Union, the Jews, although they officially belong to a Jewish nationality, do not enjoy this right. The existence of the State of Israel, encourages and strengthens Jewish feelings, although under the conditions of the Communist regime they have no organized or cultural expression. The Jewish problem in Russia becomes more and more troublesome even from the point of view of the Russians, and it is not impossible that ultimately, and perhaps even in the next few years, they may arrive at the only real solution: the opening of the gates for the aliya of the Jews to Israel. According to reliable information, the number of Jews in Russia is three to three and a half millions. If the gates are opened it may be assumed that at least half of Russian Jewry will come to Israel, and the State of Israel and the entire Jewish people must prepare for this possibility which involves both tremendous difficulties and beneficial prospects such as we have not yet known, for the State and the future of the Jewish people as a whole.

Even though over 80 percent of Diaspora Jewry is concentrated in the two great world powers, we must not neglect the Jewish communities in the other prosperous countries, in Western Europe, Canada, Latin America, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Conditions in these countries are not exactly identical with those in the United States, but there is a considerable resemblance. Here, too, there is no point in engaging in abstract prognoses. What we have to deal with is methods of work and the means of deepening the consciousness of the Jewish mission and Jewish unity. In my opinion these methods are threefold:

- Hebrew education, the central place in which will be held by the study of the Book of Books.

- The intensification of the personal bond with Israel in all forms: visits; investments of capital; education of children, youth and university students in Israel for longer or shorter periods of time; training for the best of the youth and the intelligentsia to fit them to join the builders and the defenders of the country.

- Deepening the attachment to the Messianic vision of redemption that is the vision of Jewish and human redemption held by prophets of Israel.

These three elements are the common denominator which can unite religious, orthodox, conservative, reform and free-thinking Jewry, and give Jewish meaning, purpose and significance even to those Jews who will not join in the process of the ingathering of the exiles. It is these three elements that can serve as a moral and cultural bond between Diaspora Jewry and Israel. Attachment to Hebrew culture, and first and foremost to the Book of Books, in the original; to Israel; and to the Messianic vision of redemption, redemption both Jewish and human; that is the three-fold cord which can unite and bind together all sections of Jewry, of all parties and of all communities, and — if we will it, it shall never be broken.