By Ken Stein The ripe conditions that prefaced the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli treaty and might presage additional Arab-Israeli agreements are almost totally absent in 2025. Why? Today, there is an absence of political will, courage and...

By Topic

Find content relevant to your specific interests or area of study.

By Type

Choose the format that best suits how you want to engage with the content.

By Language

Access content in the language that best supports your learning.

By Era

Explore content organized by historical period to focus your learning by timeframe.

By Ken Stein The ripe conditions that prefaced the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli treaty and might presage additional Arab-Israeli agreements are almost totally absent in 2025. Why? Today, there is an absence of political will, courage and...

The following scholars, academics, think-tank leaders and other academics offer their thoughts on israeled.org. “CIE’s website is the most comprehensive and reliable resource pertaining to the modern State of Israel that I know of. With…

Maya Rezak and Ken Stein, February 8, 2026 Hussain Abdul-Hussain, “Why Is Saudi Arabia Abandoning Peace?” The National Interest, January 23, 2026. Oded Ailam, “‘The Glass Wall’: How Israel Turned Intelligence Into an Insurance Policy…

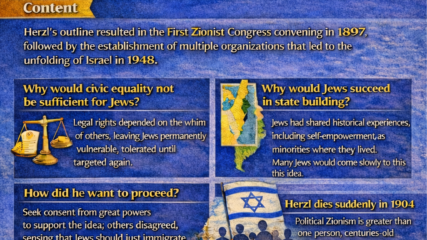

Nine questions guide key understandings about Theodor Herzl’s “The Jewish State.”

Israel is competing in bobsled, alpine and cross-country skiing, skeleton, and figure skating at the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan and Cortina, Italy.

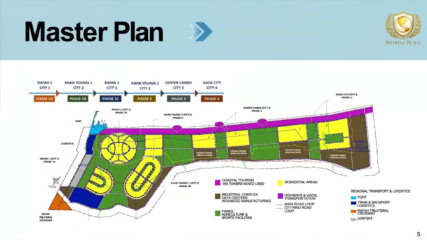

While the Palestinian official leading the technocratic Gaza administration promises to open the Rafah Crossing and the Bulgarian high commissioner for Gaza urges the world to focus on the big picture, U.S. envoy Jared Kushner lays out a vision for Gaza as a rapid, phased real estate redevelopment.

A Zionist delegation to the Paris Peace Conference makes an effective, largely successful case for the League of Nations to incorporate a future Jewish national home into the British Mandate for Palestine.

The Trump administration’s proposed charter for the Board of Peace, the body the United Nations has charged with overseeing the Gaza ceasefire, does not mention Gaza or any other specific location of operation but does grant its chairman, Donald Trump, extensive control over its mission and operations.

Three years after the Israeli government began the process to overhaul the judiciary, and after two years of war delayed efforts, the drive to rein in judicial independence continues.

Former Supreme Court President Aharon Barak makes the case against the Netanyahu government’s efforts to overhaul the judiciary, arguing that Israeli democracy requires judicial independence and protection for minority rights.