May 14, 1947

The British, facing increased violence in Palestine and pressure to expand Jewish immigration in the wake of the Holocaust, formally turned to the new United Nations for advice in early April 1947. In doing so, the British made clear that they would not be bound by any recommendations which they deemed as unfavorable to their national interests. After receiving approval from all but one of the body’s 55 member countries — only Abyssinia (Ethiopia) objects — the United Nations set April 28 for a special session on Palestine. On that morning, Brazilian Foreign Minister Oswaldo Aranha was appointed the president of the special session, and a steering committee was established to set the agenda.

After the first meeting of the special gathering, days of debate in both the U.N. General Assembly and steering committee took place. Among the issues were whether to allow the Jewish Agency to be represented in the discussions, Arab demands for independence in Palestine and the creation of a fact-finding commission to further investigate the Palestine question.

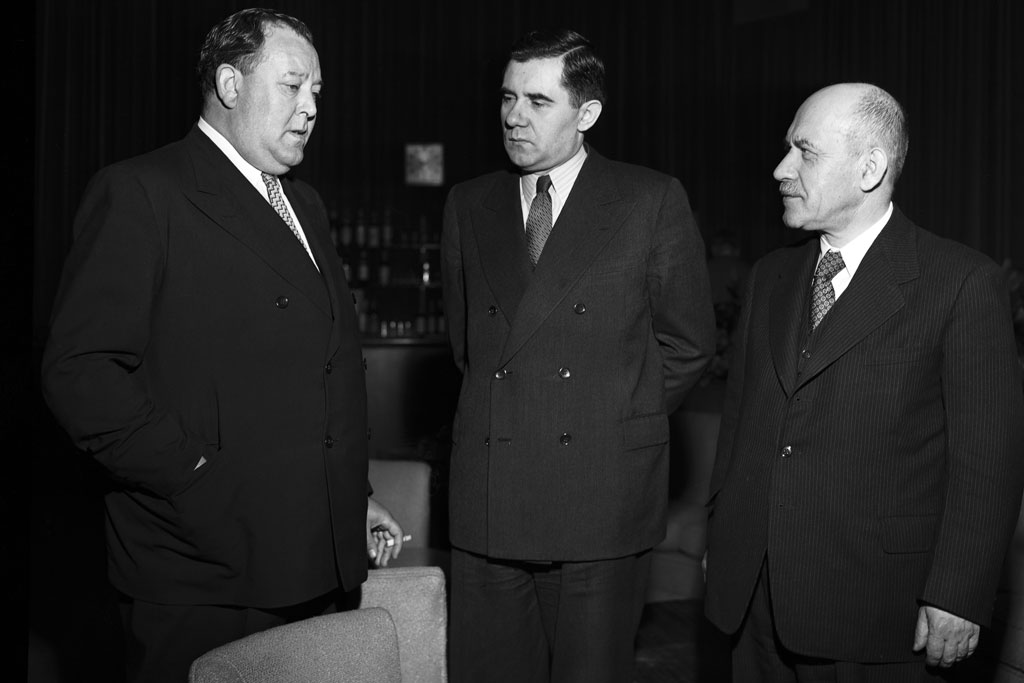

On May 14, Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko addresses the special session on the issue of Palestine. Gromyko highlights the failures of the Mandate system in Palestine, especially its inability to solve the “question of mutual relations between the Arabs and the Jews, which is one of the most important and acute questions, and that this administration has not ensured the achievement of the aims laid down when the mandate was established.”

He acknowledges the great suffering of the Jews during World War II and the hardships imposed on the survivors. Calling for action, he says, “The time has come to help these people, not by word, but by deeds.”

Gromyko accepts the right of Jews to self-determination, saying the inability of Western European states to protect their Jewish citizens “explains the aspirations of the Jews to establish their own state. It would be unjust not to take this into consideration and to deny the right of the Jewish people to realize this aspiration. It would be unjustifiable to deny this right to the Jewish people, particularly in view of all it has undergone during the Second World War.”

Despite this admission of the Jewish right to self-determination, Gromyko accentuates the concept of a unitary independent state in Palestine for Arabs and Jews, a view supported by Arab states. In his conclusion, however, Gromyko surprises most observers by saying, “If this plan proved impossible to implement, in view of the deterioration in the relations between the Jews and the Arabs — and it will be very important to know the special committee’s opinion on this question — then it would be necessary to consider the second plan, which, like the first, has its supporters in Palestine and which provides for the partition of Palestine into two independent autonomous states, one Jewish and one Arab.”

The following day, May 15, 1947, the special session passes U.N. General Assembly Resolution 106, which establishes the U.N. Special Commission on Palestine “to prepare for consideration at the next regular session of the Assembly a report on the question of Palestine.” Its purpose, like previous commissions that visited Palestine, is to investigate underlying causes for communal unrest and to make political recommendations about next political steps.