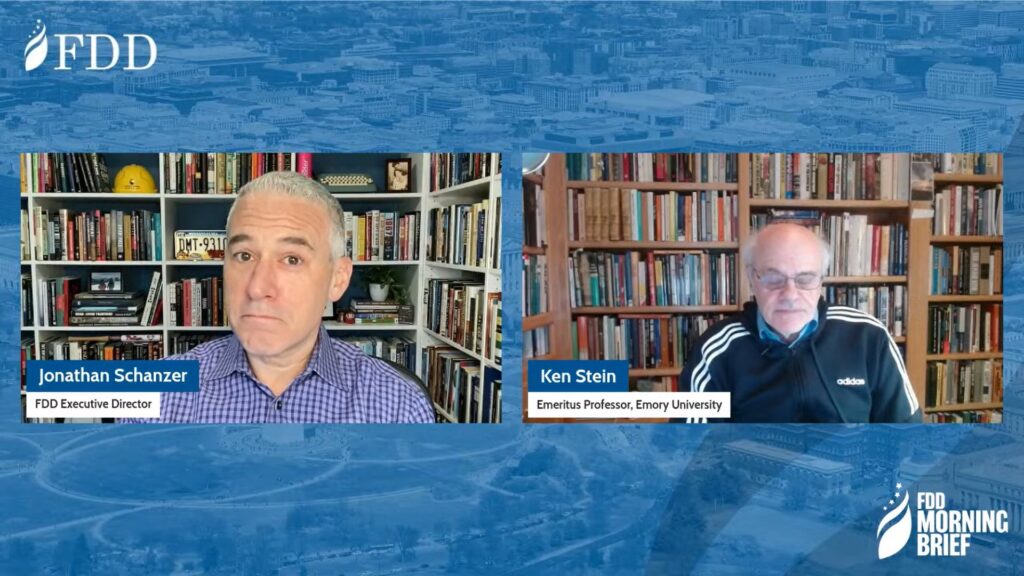

CIE President Ken Stein is interviewed about Jimmy Carter by Foundation for Defense of Democracies Executive Director Jonathan Schanzer on the “FDD Morning Brief” on January 6, 2025. Jonathan Schanzer: It’s now time for my...

By Topic

Find content relevant to your specific interests or area of study.

By Type

Choose the format that best suits how you want to engage with the content.

By Language

Access content in the language that best supports your learning.

By Era

Explore content organized by historical period to focus your learning by timeframe.

CIE President Ken Stein is interviewed about Jimmy Carter by Foundation for Defense of Democracies Executive Director Jonathan Schanzer on the “FDD Morning Brief” on January 6, 2025. Jonathan Schanzer: It’s now time for my...

CIE President Ken Stein addresses what is and what is not known about why Hamas attacked October 7, 2023, why Israel was caught off guard, and what happens after the war across the region.

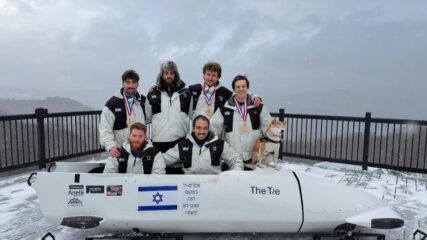

Israel wasn’t expecting gold, silver or bronze in the 2026 Winter Olympics, but it also wasn’t expecting controversy to mar the happy story of its first Olympic bobsledders.

CIE President Ken Stein briefly reviews the 2023-2025 Hamas-Israel war and examines the short- and long-term consequences.

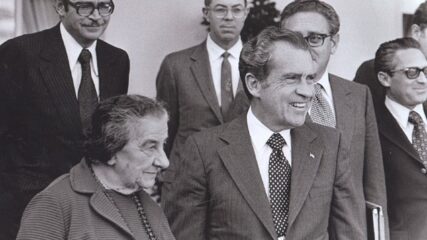

Using published archives, press conferences, speeches and numerous interviews, this compilation of quotations traces how official American views on Zionism and Israel have evolved over a century.

In the waning days of the Reagan administration, Secretary of State George Shultz pushes for U.S.-mediated peace negotiations, including Palestinians, and offers the outlines for a resolution to the conflict.

The following scholars, academics, think-tank leaders and other academics offer their thoughts on israeled.org. “CIE’s website is the most comprehensive and reliable resource pertaining to the modern State of Israel that I know of. With…

Maya Rezak and Ken Stein, February 8, 2026 Hussain Abdul-Hussain, “Why Is Saudi Arabia Abandoning Peace?” The National Interest, January 23, 2026. Oded Ailam, “‘The Glass Wall’: How Israel Turned Intelligence Into an Insurance Policy…

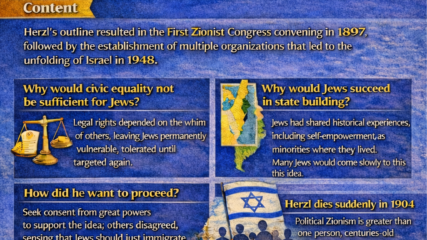

Nine questions guide key understandings about Theodor Herzl’s “The Jewish State.”

Israel is competing in bobsled, alpine and cross-country skiing, skeleton, and figure skating at the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan and Cortina, Italy.