(22 November 1967)

United Nations. Security Council. Resolution 1967/242. 22 November 1967.

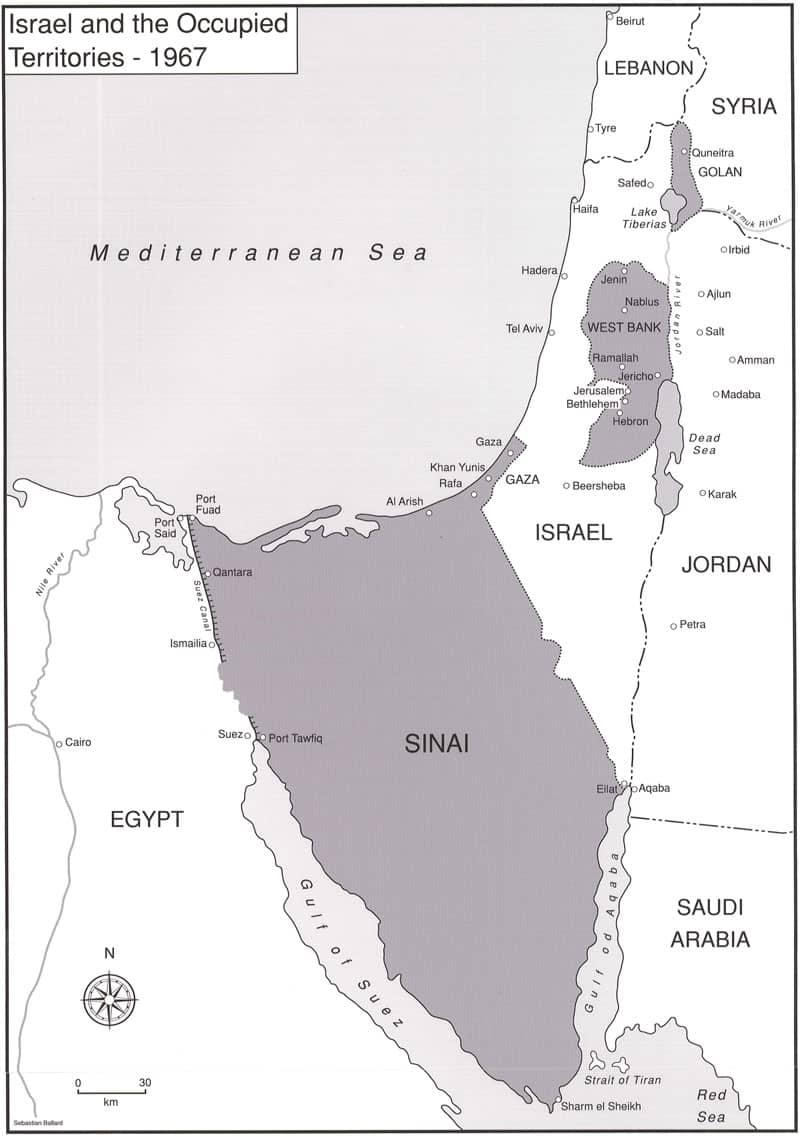

Adopted on November 22, 1967, in the wake of the June 1967 Middle East War, United Nations Security Council Resolution 242 became the context and framework for subsequent official Arab- Israeli negotiations. [1] Given the changes in regional and international politics, the resolution has remained central to the conflict’s resolution; it has not been replaced or amended. Both the resolution’s ambiguity and its omissions gave it prolonged life and interminable interpretations. The central concept in the resolution is an Israeli exchange of land that it won in the 1967 war – the Sinai Peninsula, the Golan Heights, portions of Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip – for peace to be granted by Arab neighbors and states. The popular shorthand of the resolution remains “land for peace.” The resolution includes a formula for achieving peace, namely withdrawal from lands Israel won in the June 1967 war, without establishing specifically how much land should be returned for what nature of peace. It called for “withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict,” without stating how much withdrawal should take place, in the belief that the respective sides would judge what the final borders should be. However, the resolution was specific in its call for the “termination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgment of the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and political independence of every State in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force.” It also affirmed the need for “guaranteeing freedom of navigation through international waterways in the area, and for achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem.”

Commenting on the resolution’s ambiguity with respect to exchanging land for establishment of final borders (in his secret conversations with Hafez Ismail, Egypt’s National Security Adviser) in February 1973, U.S. National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger noted that Resolution 242 “passed only because all the parties thought they could give the phrases the meaning they preferred.”[2] In the academic and policy-making communities, entire publications have been devoted to interpreting the resolution’s meaning and scope. [3] The Resolution is as important for what it includes as for what it omits. At the time of the June 1967 war, the Arab- Israeli conflict was understood as a state-to-state conflict; the Palestinians had not yet achieved recognition by the international community or by Israel as its core adversary. Thus, the Palestinians were not mentioned by name as the Palestinian people, nor was there any mention of ‘Palestinian self-determination,’ or the establishment of a future ‘Palestinian state.’ Resolution 242 referenced solving the ‘refugee problem’ without a precise indication of which refugees should have their status changed, though the assumption was that this referred to some or all of the Palestinians displaced by the 1947-1949 Arab-Israeli War, as well as those more recently displaced by the June 1967 war. The resolution did not define the 1967 war as a war of aggression, as Arab states and the Soviet Union had wanted in the resolution; nothing was definitively said about the future of the Gaza Strip or the West Bank, which had been occupied and administered by Egypt and Jordan respectively since 1949. Nothing was said about earlier resolutions dealing with Palestine’s partition or the refugee issue. Moreover, it did not call for direct negotiations between the parties. Instead, it maintained that mediation similar to the 1948-49 armistice negotiations was the appropriate negotiating mechanism, and it called on the UN to be that mediator. Intentionally or not, the stipulation for third-party mediation reinforced the consensus Arab view and strong preference not to enter into any direct negotiations with Israelis. Months before the passage of Resolution 242, the August 1967 Khartoum Arab summit conference called for ‘no negotiation, no recognition, no peace’ with Israel. ‘Direct negotiations’ between the parties to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict was not requested by anyone until UNSC Resolution 338 was passed in the days immediately following the end of the October 1973 War. By then, the mediation had fallen into the hands of the Americans and away from the United Nations. Direct political level negotiations did not take place until Egyptian President Anwar Sadat visited Israel in November 1977.

Specifically, the resolution considered the results of the June 1967 War and Israel’s occupation of territories previously controlled by Syria, Jordan, and Egypt, but it also considered the unstable and indefensible 1949 Arab-Israeli armistice lines. In other words, the resolution aimed to create borders — not boundary lines or armistice lines like those that remained from 1949 — and at making those borders tenable. As a junior senator from Texas, Lyndon Johnson observed firsthand Israel’s forced withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula in March 1957. As President ten years later, witnessing the June War, Johnson shaped the war’s diplomatic aftermath.

According to then-Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs Joseph Sisco,“the one thing that influenced Johnson the most at the time [was] that he saw the Eisenhower role…that we forced the Israeli withdrawal, and Johnson’s view was that the Israelis got very little in return [then] and so that this time the approach was far less the notion that there should be total Israeli withdrawal, but rather, in the aftermath of the war we should try to do was to try to establish a structure, a framework, for peace.” [4] Johnson took the view that when Israel withdrew from the territories this time, final treaties, not some interim arrangement, should be the outcome of negotiations. In an address to a conference of educators on June 19, 1967, five months before UNSC Resolution 242 was unanimously passed by the Security Council, Johnson provided the five policy principles that became the core concepts for UN resolution 242. Johnson said, “…Now, finally, let me turn to the Middle East—and to the tumultuous events of the past months. Those events have proved the wisdom of five great principles of peace in the region. The first and the greatest principle is that every nation in the area has a fundamental right to live, and to have this right respected by its neighbors…. Each nation, therefore, must accept the right of others to live. Second, [there]… is a human requirement: justice for the refugees. The nations of the Middle East must at last address themselves to the plight of those who have been displaced by wars. There will be no peace for any party in the Middle East unless this problem is attacked with new energy by all, and certainly primarily by those who are immediately concerned. A third lesson is that maritime rights must be respected. The right of innocent maritime passage must be preserved for all nations. Fourth, this last conflict has demonstrated the danger of the Middle Eastern arms race of the last 12 years. Here the responsibility must rest not only on those in the area—but upon the larger states outside the area. Now the waste and futility of the arms race must be apparent to all the peoples of the world. And now there is another moment of choice. The United States of America, for its part, will use every resource of diplomacy, and every counsel of reason and prudence, to try to find a better course. Fifth, the crisis underlines the importance of respect for political independence and territorial integrity of all the states of the area. We reaffirmed that principle at the height of this crisis. We reaffirm it again today on behalf of all.” [5]

While Johnson’s principles became the resolution’s outline, key State Department and White House officials involved in the negotiations recollect that the debate over the wording of the resolution was long, tedious, and intentionally ambiguous. The phrase “withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict” became the most controversial, repeatedly debated, and misinterpreted phrase in the resolution. There were half a dozen drafts of the resolution that were not accepted, including several that included a phrase specifically calling for “withdrawal from all the occupied territories.”[6]

However, each of those drafts of the resolution was defeated. The word ‘all’ never made it into the final resolution. The final draft of the resolution was drawn up by the British representative to the United Nations, Lord Caradon (Hugh Foot), who had his first posting in the British colonial service as an administrative officer in Palestine in the 1930s. Caradon always asserted that nothing was exactly specified by ‘withdrawal.’ While the resolution was being drafted, “speaker after speaker [at the UN] made it explicit that Israel was not to be forced back to the “fragile and vulnerable” Armistice Demarcation Lines, but should retire, once peace is made, to what UNSC 242 called “secure and recognized boundaries agreed to by the parties.” [7] The term “secure and recognized boundaries” was never fully defined. Likewise, American drafters of the resolution believed that the resolution was meant to be implemented in all its parts, “linked together to make a balanced whole, to be carried out together or not at all.” [8] Sisco, who was intimately involved in the drafting of the resolution, said that the “resolution did not say ‘withdrawal to the pre-June 5 lines.’”

Though the resolution was drafted in English, it was the French translation of the resolution that Arab states and supporters of full Israeli withdrawal from the territories constantly cited as the proper meaning and only interpretation of 242. The reason was simple: in French, the key phrase, “withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict,” is translated as “retrait des forces arrives Isreliennes des territoires occupes lores due recent conflit.” The English version intentionally omits the definite article “the” before the word “territoires,” leaving imprecise the amount or whereabouts of territory from which Israel might be expected to withdraw. By contrast, the French text because of the requirement in the French language to add an article prior to a noun necessitated the phrase “des territoires,” specifying “the” territories, which was often presented by supporters for full or total Israel withdrawal as “the territories,” or, even more inaccurately: “from all the territories.” Political leaders and spokesmen for all sides have given their interpretation of what withdrawal mean. Meir Rosenne, who served as legal adviser to the Israeli Foreign Ministry from 1971-1979, cogently argued that the French translation cannot be accepted because under international law the accepted procedure when there are clashing texts is to give preference to the text that was originally submitted, in this case English.[9] By contrast, Nabil Araby, who served in the Egyptian Foreign ministry in several key positions, downplayed the absence of the word “the,” referring instead to the resolution’s statement of “the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by force,” a key phrase that he asserted with equal vigor is an overarching principle, appearing in the resolution’s preamble.[10] Contrary to the intention of implementing either full withdrawal or withdrawal from all the territories, Menachem Begin, as Israeli Prime Minister from 1977-1982, sought to exchange only the territory of Sinai for a peace treaty with Egypt. Begin did not want to apply UNSC Resolution 242 to the Golan Heights, and, more specifically, not to East Jerusalem, the West Bank, or the Gaza Strip. Begin once remarked to long-time adviser Yahiel Kadishai that “we actually fulfilled [242] by relinquishing the Sinai, we did our share.”[11] In 1991, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir’s political adviser explained that “a Likud man does not give up areas inside Eretz Yisrael, right? Nevertheless, we did give up 95 percent of the territory in the Sinai to which UN Resolution 242 applies, right? Well, in handing over such a high percentage of the territories we fulfilled our part of Resolution 242.”[12]

The Resolution stated that the parties must negotiate to achieve agreement on the so-called “final, secure, and recognized borders. In other words, the question of the final borders was to be a matter of negotiations between the parties.” [13] Israel accepted the resolution in May 1968. Egypt and Jordan accepted 242 with the explicit understanding that it required Israel to withdraw unconditionally from all the occupied territories captured in the June 1967 war. Until February 1971, Syria fully rejected the resolution and then hinted, as Syrian President Assad said publicly and clearly, that he would not oppose the implementation of 242 as long it ensured full Israeli withdrawal from all Arab lands and the fulfillment of all Palestinian rights. For Assad, fulfillment of Palestinian rights meant the right of any Palestinian to return to pre-1967 Israel. Assad accepted the portion of the resolution that spoke about the inadmissibility of acquiring territory in war, but he did not refer to making peace with Israel. By attending the 1991 Madrid Peace conference, Syria accepted the invitation to a conference that mentioned 242, but did not indicate that it was prepared to recognize Israeli sovereignty and territorial integrity as deemed by the resolution.

UNSC 242 bedeviled the PLO. Until 1988, the organization refused to accept the resolution for a variety of reasons. First, the original resolution made no mention of Palestinians or Palestinian political rights; second, recognition meant implicitly recognizing Israel’s right to exist and the prospect of “living free from the threats of force,” which for the PLO meant removing the option of armed struggle, freedom fighting, or terrorism against Israel or Israeli targets. In the 1970s and well into the 1980s, the PLO was not willing to relinquish armed struggle as a core political tool applied against Israel. In 1988 and 1989, when discussion was ripe to convene an international Middle East conference, Yasir Arafat, chairman of the PLO, provided conditional acceptance of 242, on the assurance of a Palestinian state, self-determination, and repatriation; his approval of 242 “included all UN resolutions, not just one resolution.”[14] For the Palestinians, this meant that if they accepted 242, the international community would, in Arafat’s view, be obliged to apply UN General Assembly Resolution 194 of 1949, which the PLO, most Palestinians, and most in the Arab world interpreted as their right to return to all the land which constitutes Israel.

Presidents Richard Nixon, George W. Bush, and Jimmy Carter each weighed in differently on the meaning of 242. Nixon told Kissinger during the early days of the October 1973 War, “You and I know they [the Israelis] can’t go back to the other [pre-1967] borders. But we must not, on the other hand, say that because the Israelis won this war, as they won the ’67 war, that we just go on with the status quo. It can’t be done.” [15] When George W. Bush exchanged letters with Israeli Prime Minister Sharon about the future of Israel’s borders in 2004, he made it clear that Israel did not have to return to the 1949 armistice lines, essentially the 1967 boundary demarcation. In March 1977, Carter, prior to his major engagement in Israeli-Egyptian diplomacy, said that “the Arab nations, the Israeli nation, had to agree on permanent and recognized borders, where sovereignty is legal as mutually agreed. Defense lines may or may not conform in the foreseeable future to those legal borders. There may be extensions of Israeli defense capability beyond the permanent and recognized borders.”[16] Thirty years after he left office, Carter erroneously stated that the resolution “mandated” or “required” Israeli withdrawal from the territories taken in the June 1967 war, which, if applied, meant there would be no need for an Arab side to negotiate with Israel prior to withdrawal to establish the parameters for peace, and it would be contrary to Lyndon Johnson’s specific intention. [17]

Finally, delay by Arab sides in accepting Israel’s legitimacy or its existence as a Jewish state, resulted in the unwillingness to open negotiations with Israel based on 242, gave Israeli leaders a virtually open opportunity to interpret 242 as they wished. Egypt’s President Sadat opened public negotiations with Israel a decade after the resolution’s passage, and in an exchange of land for peace, all of Sinai was returned to Egyptian sovereignty. Not being ready to negotiate with Israel, immediately after the resolutions passed with or without 242 as a basis for talks, resulted in the Israeli government’s consideration and then readiness to change the demography of the newly acquired territories. Israeli government policy to build settlements in the areas won in the June 1967 War might have been fully avoided had the Arab-Israeli negotiations evolved in the late 1960s. Israel was never tested by Arab states, to withdraw from these lands with or without UNSC 242 used as a framework for negotiations.

-Ken Stein, April 2010

The Security Council, Expressing its continuing concern with the grave situation in the Middle East; Emphasizing the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war and the need to work for a just and lasting peace in which every State in the area can live in security; Emphasizing further that all Member States in their acceptance of the Charter of the United Nations have undertaken a commitment to act in accordance with Article 2 of the Charter;

- Affirms that the fulfillment of Charter principles requires the establishment of a just and lasting peace in the Middle East which should include the application of both the following principles:

- Withdrawal of Israel armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict;

- Termination of all claims or states of belligerency and respect for and acknowledgment of the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and political independence of every State in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force;

- Affirms further the necessity:

- For guaranteeing freedom of navigation through international waterways in the area;

- For achieving a just settlement of the refugee problem;

- For guaranteeing the territorial inviolability and political independence of every State in the area, through measures including the establishment of demilitarized zones;

- Requests the Secretary-General to designate a Special Representative to proceed to the Middle East to establish and maintain contacts with the States concerned in order to promote agreement and assist with efforts to achieve a peaceful and accepted settlement in accordance with the provisions and principles in this Resolution;

- Requests the Secretary-General to report to the Security Council on the progress of the efforts of the Special Representative as soon as possible.

Adopted unanimously at the 1382nd meeting.

[1] Its mention and terminology are found as the basis for convening the December 1973 Geneva Middle East Peace Conference, the aborted October 1977 U.S.-Soviet Declaration, and the September 1978 Camp David Accords. The resolution is the central concept of the March 1979 Egyptian-Israeli and the October 1994 Jordanian-Israeli Treaties. Acceptance of the resolution’s content was a pre-requisite for the opening of the U.S.-PLO dialogue in December 1988 and the convocation of the Madrid Middle East Peace Conference in October 1991. Reference to 242 is centrally placed in several U.S.-Israeli memoranda of understanding about the conduct of future negotiations, the 1980 Venice Declaration of nine European countries for Middle East peace, the September 1993 Israel-PLO Oslo Accords, the October 1998 Wye Accords, the March 2003 Road Map for Peace, and the exchange of letters between President George W. Bush and Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon in April 2004. The March 2002, Beirut Arab summit Declaration, also known as the Arab Peace Initiative does not include mention of 242, nor for any apparent reason was it mentioned as a term of reference in the convocation of the November 2007 PLO-Israeli Annapolis summit. [2] Memorandum of Conversation between Muhammad Hafiz Ismail and Henry Kissinger, 25 February 1973, Armonk, New York, Nixon Presidential Materials Project, NSC Files, Henry Kissinger Files, Middle East, Box 25. [3] For example see an excellent summary by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, UN Security Council Resolution 242 Building Block of Peacemaking, Washington, D.C., 1993; David Korn, The Making of United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, Pew Case Studies in International Affairs, Case 450, Washington, D.C, The Pew Charitable Trusts, 1992; and The Journal of Palestine Studies, Autumn 2007, Vol. XXXVII, Number 1. [4] Remarks by Joseph Sisco, Minutes of a Private Meeting, United States Institute for Peace, Washington, DC, April 3, 1991. [5] Address by President Lyndon Johnson, National Foreign Policy Conference of Educators, Washington, D.C., Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon B. Johnson, Office of the Federal Residence, Washington, D.C.,June 1967.[6] Gideon Rafael (Israel’s Ambassador to the UN in 1967), Destination Peace/ Three Decades of Israeli Foreign Policy/ A Personal Memoir, New York: Stein and Day, 1981, pp. 189-190.

[7] Eugene Rostow (Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs, 1966-1969), “The Intent of UNSC Resolution 242—The View of Regional Actors,” in The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, UN Security Council Resolution 242/ The Building Block of Peacemaking, Washington, D.C. 1993, p. 17. Examples of the detailed discussion leading up to the resolutions passage see U.S. Department of State, Foreign Relations 1964-1968, XIX, Arab-Israeli Crisis and War, 1967. Documents 481-504.

[8] Remarks by Alfred L. Atherton, Jr. Assistant Secretary of State of Near East and South Asian Affairs), AA Status Report on the Peace Process, address to the Atlanta Foreign Policy Conference on U.S. Interests in the Middle East, April 5, 1978.[9] Meir Rosenne, “Understanding UN Security Council Resolution 242 of November 22, 1967, on the Middle East,” in Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, Defensible Borders for a Lasting Peace, Jerusalem, 2005.

[10] Remarks by Nabil Araby, “The Intent of UNSC Resolution 242—The View of Regional Actors, “ in UN Security Council Resolution 242 The Building Block of Peacemaking, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1993, pp. 35-44.

[11] Kenneth W. Stein, interview with Yahiel Kadishai, Tel Aviv, Israel, July 5, 1993.

[12]Remarks by Yossi Ahime’ir, Yedi’ot Aharonot Shiv’a Yamim supplement, August 23, 1991. [13] Remarks by Joseph Sisco, NBC’s “Meet the Press,” 12 July 1970. [14] Text from Manama News service, Bahrain, January 5, 1989, Foreign Broadcast Information Service-Near East and South Asia, U.S. Department of Commerce, Washington, D.C.[15]Henry Kissinger, Crisis: The Anatomy of Two Major Foreign policy Crises, New York: Simon and Schuster, 2003, p.140.

[16] Remarks by Jimmy Carter, as quoted in Presidential News Conference, March 9, 1977, The American Presidency Project, www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/print.php?pid=7139.[17] See remarks by Jimmy Carter, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid, Simon and Schuster, November 2006, pp. 38-39, 207, 208, and 215. See also Carter’s acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, December 10, 2002; presentation before the Council on Foreign Relations, March 2, 2006; and the opinion piece that appeared in 70 newspapers (so claimed by the Carter Center). These remarks can all be found either on the Carter Center website (under news/documents), www.cartercenter.org, or on National Public Radio’s “Fresh Air” website, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6543594.