Ken Stein, President, Center for Israel Education, May 19, 2025

Introduction

Since 1937, the idea of geopolitically separating Jewish and Arab populations west of the Jordan River has been a recommended solution to mitigate violence between the populations. While this political outcome has been supported by hundreds of international and regional voices, at no time in nine decades have Palestinian and Israeli leaders directly or indirectly possessed sufficient will and courage to negotiate, engineer and fund a two-state outcome. Above all, leaders must tell the other side and show by demonstrated trust that their side fully agrees that whatever arrangement will end once and for all the conflict between them; otherwise, no two-state solution is possible. Moreover, loud and influential constituencies in the Palestinian and Israeli communities, as well as regional actors, continue to engage in multiple violent actions.

Still, statements continue in favor of a two-state political outcome, however that end might be aspirationally outlined, and dozens of plans, schemes, road maps and frameworks defining borders and addressing other issues have been put forward.

The voices advocating for a two-state outcome remain loud and constant, but they are analysts, editorial writers and politicians who are disconnected from what the people on the ground want or do not want. Advocates for a two-state solution are not being realistic; they are relentlessly hopeful. Advocates of a two-state solution in spring 2025 probably do not regularly read or comprehend the voices presented in either Arabic or Hebrew publications or blogs where the true sentiment of communal disparagement and vile distance percolates almost daily. Arabic newspapers habitually refer to Israel as the “occupying state,” and that is not in reference to the West Bank or Gaza Strip. As Samuel B. Lewis, the U.S. ambassador to Israel from 1977 to 1985, told a conference in Miami in 2011, “The mediator to the Arab-Israeli conflict cannot want an agreement more than the respective parties.”

In 2025, Hamas, Islamic Jihad and many secular-oriented Palestinians oppose any Jewish state under any conditions west of the Jordan River. On the other side, members of the Israeli political right and their affiliates view all the land of Judea and Samaria as integral to the Jewish patrimony. Both sides refuse to consider sharing the land in a manner that allows two separate political entities. Surveys by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR) and the Israel Democracy Institute from late 2023 to the present show significant minorities in both populations favoring a two-state solution.

Palestinians’ and Israelis’ hopes and anger are disconnected from the international community of voices, who appear to hope that continual advocacy and promotion of a two-state political outcome will erode obstinacy and eventually produce two states. In a May 2025 poll by PCPSR, four out of 10 Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza supported a two-state solution, with no information available for Palestinians outside those areas.

A profoundly weak, divided and dysfunctional Palestinian political community is denying the commencement or even serious consideration of devolution to a two-state outcome. Perhaps the Palestinian political community in 2025 is the most divided geographically and politically in a century-long evolution. Both the Palestinian Authority and Hamas are dominated by elites, autocracy, kleptocracy, nepotism and poorly developed civil institutions. Palestinian factions do not want to talk to or compromise with one another, let alone come to an agreement on what the Palestinians will relinquish to Israel.

The distance between Hamas and the PLO-controlled Palestinian Authority has not been bridged since Hamas took over Gaza in 2007. Perhaps Palestinians of all hues intend to come together to take advantage of the billions that might flow into rebuilding Gaza? An alliance of convenience or one of conviction? Few can logically argue that after 19 months of war, a majority of Israelis, let alone the Israeli government, are willing to trust Palestinian intentions, particularly in a regional setting where half of Israel’s contiguous neighbors are in the midst of massive political upheavals. When Israel and Egypt made their agreements with each other in the 1970s, at least until the fall of the Shah in 1979, the region around Israel was highly stable, not sitting on volcanic and toxic ideologies.

On the Israeli side, absolutely no consensus, not even a plurality, exists after October 7 to take a chance on withdrawal from any lands that might even slowly evolve into a Palestinian state. Neither Palestinian nor Israeli leaders in spring 2025 can even consider persuading their respective communities that a two-state solution should or must be over the horizon. Who will provide $3 billion a year for a decade to support a budding Palestinian state economy? That sum would be separate from what is required to rebuild the Gaza Strip. Will Muslim and Arab states agree not to interfere in an implementation process where the outcome will be the slow evolution and mutual acceptance of places for two populations?

Nineteen months after the outbreak of the Hamas-Israel conflict in October 2023, the best that politicians could hope for was the separation of the populations, applied perhaps over five years, in a process that could involve some form of a trusteeship.

(From left) Israeli territory from 1949 to 1967; the West Bank and Gaza Strip; Israeli settlements in the West Bank in 2005.

Meanwhile, a loud minority advocates one state for both peoples. That idea is a nonstarter for Israelis, who refuse to give up Zionism’s fundamental principle of a territorial Jewish majority. The intention of one-state advocates is not subtle: They seek the elimination of Jewish territorial sovereignty and the erasure of the Zionist effort that built and sustained a Jewish state the past 150 years. One-state advocates seek to negate history. They want to reboot the Palestinian Arab-Jewish relationship and cleanse history of multiple decisions that were wrong-footed, ideological and devoid of pragmatism.

Going back to April 1920, the British administration in Palestine failed to persuade the Arab and Zionist political elites to cooperate with the British government. The Arab community totally opposed the British facilitating Jewish growth. The Zionists did not want to participate in any self-governing institutions where they would be an established minority. The Zionists diligently employed the British commitment in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, as legitimized by the 1922 League of Nations Mandate, “to secure the establishment of the Jewish National Home and facilitate Jewish immigration while ensuring the rights and positions of other sections of the population are not prejudiced.”

Zionists purchased land, built self-governing political and social institutions, and brought in people to grow the national home. But the British did not promise a Jewish state.

The Arab political elite boycotted proposed British institutions such as an Arab Agency to represent Arab interests and achieve parity with the Jewish Agency (then the Palestine Zionist Executive). A significant number of Palestinian Arabs did work for the British administration as bureaucrats, clerks and heads of departments, but a political boycott was almost always employed against the British for continuing to support the development of the Jewish national home. Perhaps if the Palestinian Arabs had chosen compromise rather than boycott, they would have achieved self-determination. Throughout the Mandate, dozens of British officials in Palestine, London and elsewhere — the 1918-1920 British military administration, Ernest Richmond, Sir John Hope-Simpson, Lord Passfield, High Commissioners John Chancellor and Harold MacMichael, Sir Miles Lampson in Egypt, Ernest Bevin, and a host of bureaucrats in the Colonial Office and Foreign Office — urged the Arab elite to work with them to develop Palestinian Arab self-rule.

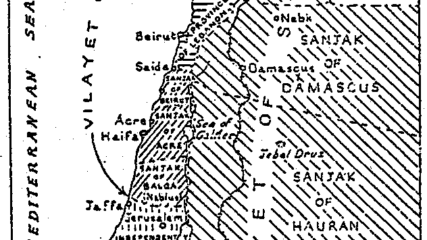

From the late 1880s, Jews and Arabs outside cities had voluntarily lived apart from each other, so when the British first proposed partition in July 1937, geopolitical separation had been happening for half a century. Eloquently and fairly, the 400-page Peel Commission Report, which suggested the partition of Palestine into two states, recounted the intricacies of British administration since 1920 and gave a sympathetic account of Jewish and Arab national aspirations. The report found that the underlying causes of the civil disturbances that began in 1936 were the same as had ignited unrest in 1920, 1921, 1928, 1929 and 1933: the Arab desire for independence, the Arab hatred and fear of the Jewish national home, and the “intensive character of Jewish nationalism.” The report concluded that the aspirations of the two communities were irreconcilable and that the British Mandate was unworkable.

For the first time, an official British government paper suggested “partition as a chance for ultimate peace.” The Peel Report recommended a “final limitation” of the boundaries of the Jewish national home; a new regime for the protection of holy places, to be guaranteed by the League of Nations to remove all anxiety that the holy places “ever should come under Jewish control”; prevention of further loss of Arab territory to future Jewish growth; and financial support for the would-be Arab state and Transjordan.

Partition would allow the Palestinian Arabs to obtain national independence and cooperate on an equal footing with the Arabs of neighboring countries in the cause of Arab unity and progress, the report said, and Palestinian Arabs would be delivered from the fear of being “swamped” by the Jews and subjected to Jewish rule. For Jews, partition would convert the prior 17 years of Jewish demographic and physical growth into a state and avoid future Arab rule. Jews in their own state could admit as many additional Jews as they themselves believed could be absorbed and thus attain the primary objective of Zionism: a Jewish nation giving its citizens the same status in the world as other nations give theirs. Partition with the creation of a Jewish state would relieve Jews of living as a minority.

The Arabs in Palestine rejected partition because they opposed any permanent Jewish presence. Zionists accepted the idea of partition but disliked the geographic limits proposed. Within a year, Britain withdrew the partition offer. In 1939, the top Palestinian Arab leader rejected a British proposal for a federal state with an Arab majority, to be established within 10 years, because he opposed all Jewish presence in Palestine.

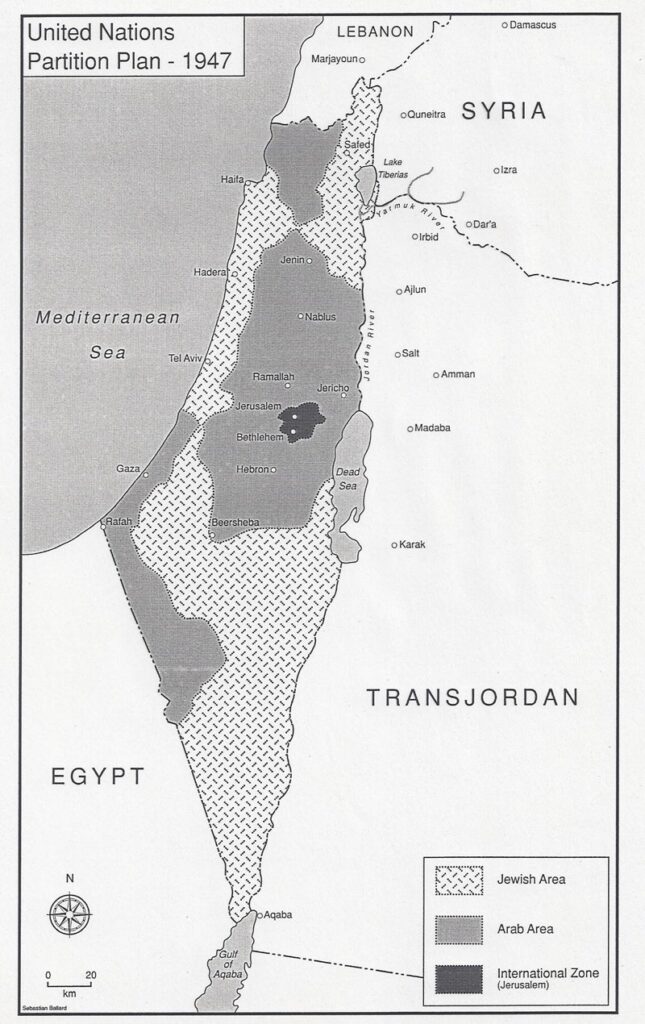

By February 1947, Britain was ready for a U.N. solution to replace its Mandate in Palestine, and the U.N. General Assembly voted for partition into Jewish and Arab states in November 1947. Each state was to compose a constitution, and they were to construct an economic union, while Jerusalem was to fall under international authority. The Zionists accepted the two-state solution; surrounding Arab states and the Palestinian Arabs vigorously opposed it. Amid war from late 1947 into spring 1949, Israel was established, but no independent Arab state emerged alongside it. Jordan took the West Bank, and Egypt administered the Gaza Strip. Massive numbers of Palestinians became refugees living in the West Bank and Gaza, surrounding Arab states, and elsewhere.

After 1947 the idea of two states for two peoples did not resurface diplomatically until the late 1990s; the 1993 Oslo Accords did not call for a Palestinian state or two states for two peoples. The notion of two states publicly promoted beginning in the late 1990s usually came with a caveat: If Arab states were going to recognize Israel, the Palestinians who left Israel and their descendants would have to be returned to their homes. This idea was vaguely stated throughout U.N. resolutions, including U.N. General Assembly Resolution 194 in 1948, speaking of refugee return. Every Israeli government balked at Resolution 194 because Israel would lose its Jewish majority. The highly touted 2002 Arab Peace Initiative referenced “applicable U.N. resolutions,” which is one reason why Israel rejected it as a negotiating framework. Hamas’ attack on Israel in October 2023 in great measure was meant to halt any Arab state from recognizing Israeli sovereignty over any part of the land from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.

From the early days of Zionism and during all of Israel’s existence, Arabs and Muslims have articulated antagonistic or mixed views toward Jews, Zionism and Israel. Israelis have listened and noted what their friends and enemies have said and generally have reacted accordingly.

— Ken Stein, May 19, 2025