Two letters detail how Arab peasants are sometimes swindled out of their lands by Arab land brokers and effendis, noting economic harm to them, and how they learn to avoid landlords and sell directly to Jewish buyers. Intra-Arab communal tension rises.

Latest articles from CIE

Israel Sends 10 Athletes to Milan-Cortina Winter Olympics

Israel is competing in bobsled, alpine and cross-country skiing, skeleton, and figure skating at the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan and Cortina, Italy.

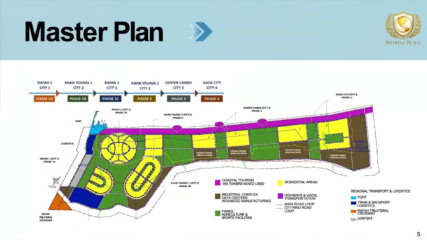

Kushner, Gaza Officials Present Rapid Gaza Redevelopment, January 2026

While the Palestinian official leading the technocratic Gaza administration promises to open the Rafah Crossing and the Bulgarian high commissioner for Gaza urges the world to focus on the big picture, U.S. envoy Jared Kushner lays out a vision for Gaza as a rapid, phased real estate redevelopment.

Zionist Organization Statement to Paris Peace Conference, 1919

A Zionist delegation to the Paris Peace Conference makes an effective, largely successful case for the League of Nations to incorporate a future Jewish national home into the British Mandate for Palestine.

Charter of the Board of Peace, January 2026CIE+

The Trump administration’s proposed charter for the Board of Peace, the body the United Nations has charged with overseeing the Gaza ceasefire, does not mention Gaza or any other specific location of operation but does grant its chairman, Donald Trump, extensive control over its mission and operations.

Status of Israel’s Judicial Overhaul, January 2026CIE+

Three years after the Israeli government began the process to overhaul the judiciary, and after two years of war delayed efforts, the drive to rein in judicial independence continues.

Aharon Barak, December 2025: Israeli Democracy Depends on Judicial IndependenceCIE+

Former Supreme Court President Aharon Barak makes the case against the Netanyahu government’s efforts to overhaul the judiciary, arguing that Israeli democracy requires judicial independence and protection for minority rights.

Israeli Supreme Court President Defends Judiciary Against Intentional Disruption (With Justice Minister’s Response), December 2025CIE+

Supreme Court President Yitzhak Amit warns about the danger to the Israeli public and democracy of sustained political attacks on the judiciary and individual judges.

Explainer: A Short History of HamasCIE+

Updated January 5, 2026; originally posted October 2023. By Ken Stein CIE+ Reliable resources for deeper Israel understanding Embrace informed content on Israel, the Middle East and the Diaspora. Begin with 7 days free to…

New Year’s 2026 Unrest in Iran and Its Context for Israel and the Middle EastCIE+

A week of unrest in Iran does not guarantee a revolution even if 85-plus million Iranians are angry at the country’s autocratic, theological rulers. Iran is a security-clerical oligarchy where kleptocracy, cronyism and authoritarianism have…