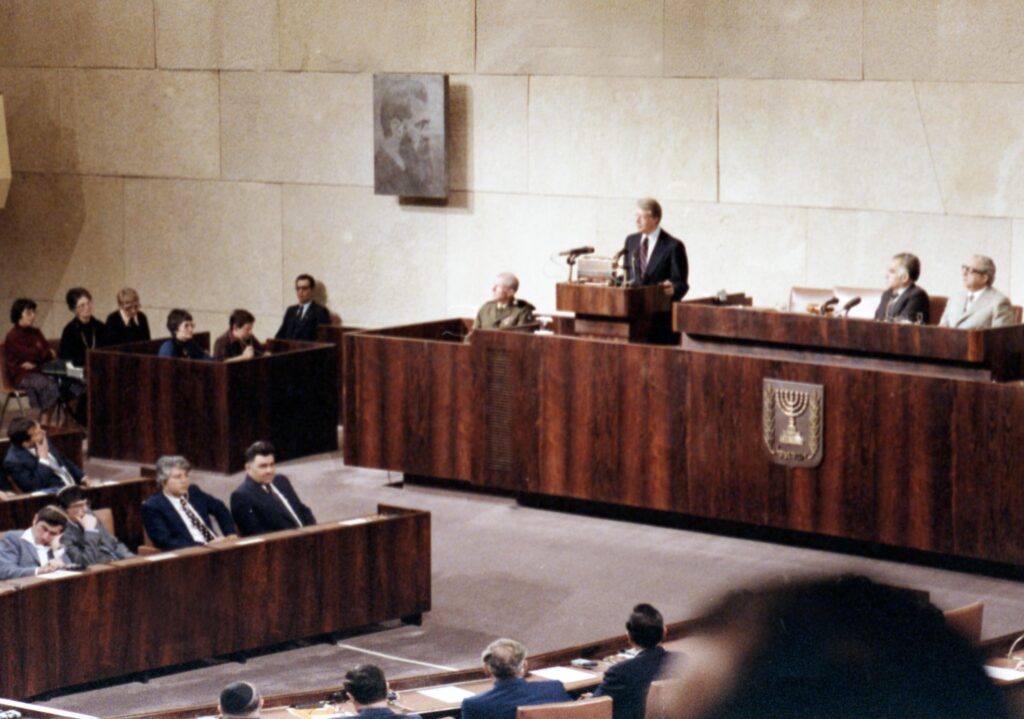

In an unprecedented presidential political gamble, President Carter meets Prime Minister Begin and then President Sadat to tie up loose ends for an Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, signed two weeks later. During the trip, he delivers the first Knesset address by a U.S. president.

Reliable resources for deeper Israel understanding

Embrace informed content on Israel, the Middle East and the Diaspora.

Begin with 7 days free to explore CIE's rich sources, expert analyses and guided knowledge building.

$39 / year

JOIN CIE+

Already have a CIE+ account?

SIGN IN