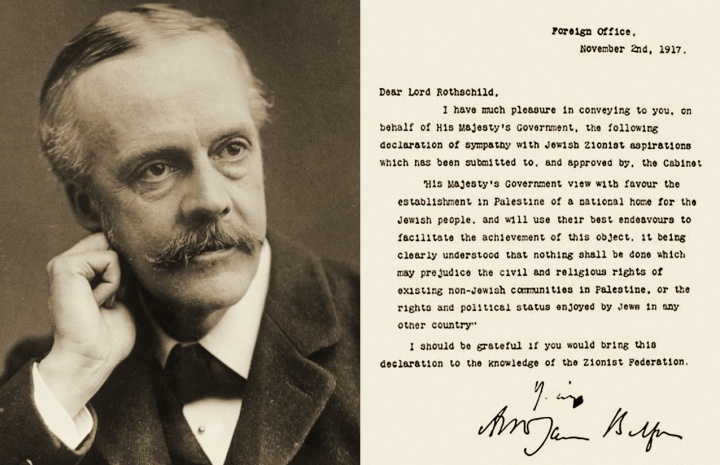

November 2, 1917

The Balfour Declaration was the Jewish charter that Herzl failed to obtain from the Ottoman sultan 20 years earlier. The terms were included in the preamble of the Palestine Mandate’s Articles in 1922 after being given international sanction and political legitimacy by the new League of Nations at San Remo in 1920.

Many historians of Zionism and Israel view the Balfour Declaration as part of a progression, from Herzl’s “The Jewish State” in 1896 through the Mandate in 1922 and U.N. General Assembly Resolution 181 in 1947, calling for separate Arab and Jewish states in Palestine and culminating in Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948. Those interested in delegitimizing Israel argue that the Balfour Declaration, and therefore anything based upon its validity, including the State of Israel, is null and void. This was the official position of most of the Arab world well into the 1990s.

The Declaration made Zionists euphoric. Recognition of their will to establish a homeland meant that the Zionist movement had received permission, first from a great power, England, and then from the League of Nations, to fulfill the objective of re-establishing a territorial base for expressing Jewish identity on the land God had promised the Jewish people. For some 40,000 Jews who had immigrated to Palestine and purchased land to build homes from the 1880s to 1917, the Declaration confirmed the justice of their ideological and physical choice to return to the land of their forefathers. For Jews worldwide, who had for centuries lived on the margins as a minority in sometimes extraordinarily hostile environments while constantly subject to the whims of rulers, protection from a great power was a major political break from the past. The Declaration’s 128 words granted permission to build a national home while promising protection for the civil and religious rights of the non-Jewish population.

For Jews who were non-Zionists or anti-Zionists, the Declaration caused worry if not profound consternation. Would non-Zionist Jews in Britain be labeled as disloyal citizens because their co-religionists were so enthusiastic about having a homeland elsewhere? Jews who opposed Zionism believed in Jewish equality or emancipation in the countries where they lived, not in a national home for Jews. These Jews weren’t sufficiently organized, and their reasoning failed to bring them much immediate or long-term notice.

A Jewish national home in Palestine supported by Great Britain fit conveniently with British strategic interests in the Middle East. Before, during and after World War I, those British interests included a land bridge from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea to ensure British economic and political influence and control from India to Egypt. For the British, the Declaration was one of many building blocks that asserted influence and territorial control over the Middle East, connecting Britain’s Arab allies, clients, kings and tribal leaders into a geopolitical network of influence across the region.

This strategy included agreements with tribal leaders in Yemen, Oman, Kuwait, Qatar, Afghanistan and the Arabian Peninsula. Securing Palestine as a geographic buffer for the British presence in Egypt and protection of the Suez Canal was necessary from Britain’s viewpoint. Thus, Zionist and British interests dovetailed into a workable and functioning symbiosis. Never to be forgotten or ignored, Arab leaders made agreements with the British and French to legitimize their control over their populations, barely considering the notion that their populations should vote or participate in self-determination.

For the Arabs living in Palestine, particularly among the politically engaged landed elites, the Balfour Declaration posed several problems. First, by establishing mandates for the Arab regions of the defunct Ottoman Empire, the French and British brought some measure of administrative efficiency to areas dominated by a few powerful families. Second, sanctioned Zionist development meant the British were not focused on establishing local control over politics by Arab elites. So dismayed were local Arab elites in the major towns of Palestine that they decided not to officially recognize the British Mandate. Instead, the political leadership boycotted official participation with the British.

Little doubt exists that the Balfour Declaration’s contents and intents were abhorrent to Arab sensibilities, and those negative feelings grew from the 1920s forward. Despite public anger at the Declaration and its inclusion in the Mandate, local Arabs did participate as members of some boards, commissions and advisory councils, magistrates, and district and subdistrict administrators and were involved in investigations of public policy issues. In other words, in public the Arab political leadership protested the British presence and protection of the Jewish national home idea, but in everyday practice many Arabs cooperated with the British and even the Zionists in Mandate operations. Offered the opportunity in the 1920s to create their own Arab Agency, the equivalent of the Palestine Zionist Executive (later the Jewish Agency), Arab leaders refused, and they boycotted the underlying principle of the Balfour Declaration well into the 1980s.

In the 21st century, the Declaration still generates visceral anger in Arabic media. It remains a rallying point for those who find the idea of a Jewish state or Jewish national home abhorrent. Arabs place unqualified blame on the British and French for denying Palestinian Arabs a place of their own after World War I, ignoring that Palestine’s Arabs were reeling in economic disaster from the war, their local leaders were at great odds with one another, and political affinities focused on a Greater Syria.

The Declaration and the Holocaust seem to rise above all other events in the memory and the historiography of the conflict’s origins. What if neither had happened? What if a declaration for Palestine’s future had been written November 2, 1917, not to Lord Rothschild, the British Zionist leader, but instead to Sharif Hussein of Mecca, the Arab leader squired by the British during the war?

Suppose that declaration hypothetically said, “My Dear Sharif Hussein. I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty’s Government, the following declaration of sympathy with the aspiration of the Arab people which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet. His Majesty’s Government view with favor the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Arab people, and will use their best endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Arab communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Arabs in any other country that might be established.”

How would the Saudis and Rashidis (the two powerful tribal families in the Arabian Peninsula) have replied to such a declaration, while they themselves were struggling through arms with the Hashemites for control over Mecca and portions of the peninsula? There was not a single Arab political leader in Palestine who could have claimed the mantle of leadership there and then for the British to pen such a promise. By issuing a declaration to one Arab family or sheik, the British would have chosen a favorite and would have alienated others who were willing to fall under the umbrella of being a “London favorite.”

Finally, 1917 was not the starting line, and the Balfour Declaration was not the starting gun. An explicit British promise to Sharif Hussein to include Palestine in an Arab kingdom would not have erased Zionist intentions to re-establish a self-governing Jewish presence in the ancient homeland. It would not have made the Palestinian economy any stronger than its depressed state during and after World War I and into the 1930s. The crystallization of Jewish focus toward Eretz Yisrael was centuries old. Modern Zionism as a national movement for the restoration of a Jewish homeland was more than half a century old before World War I. No promise to Sharif Hussein or any other Arab notable would have erased concepts, notions and plans that emerged from the writings of Herzl’s precursors, such as Alkalai, Pinsker and Hess, and contemporaries, including Ahad Ha’am, Syrkin and Gordon.

The First Zionist Congress took place 20 years before the Balfour Declaration was issued because Herzl, Ussishkin, Nordau, Weizmann and hundreds of others caught the Zionist bug long before World War I. In 1882, 25,000 Jews lived in Palestine; by 1918, 60,000-plus Zionists were in Palestine. And, critically, Zionist institutions for nation-building emerged before World War I, including the World Zionist Organization, Jewish National Fund, Palestine Office of the Zionist Organization and settlement activities by significant private individuals. No such Palestinian Arab institutions existed, and no debate about a future homeland or state can be found in Palestinian Arab writings before World War I.

Mayir Verete in his article “The Balfour Declaration and Its Makers” (Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 4, 1970, pp. 48-76) argued cogently that the Balfour Declaration was not the start of Zionism but a confirmation of what had transpired since European Jews began trickling into Palestine in the early 1880s. Jewish nation-building in thought and in practice, even if only in pregnancy or infancy, began half a century before Rothschild received the Declaration from Balfour, though the work was tedious and at times disappointing to those who first embraced Zionism. Would Zionism have been suppressed simply because a promise was made to establish an Arab state in Palestine? Would Zionists not have continued to immigrate to Palestine in the 1920s, even if illegally? Would they not have brought their personal capital to invest, and would those funds not have been just as attractive to Arab sellers of land?

In short, were not Jews working to re-establish their place in their ancient homeland well before Arthur Balfour wrote his letter to Rothschild during World War I?

— Ken Stein, August 2025