September 29, 1978

Source: FBIS-MEA-78-190, Vol V No. 190, TA280906Y Jerusalem Domestic Television Service in Hebrew 2352 GMT 27 Sep 78 TA

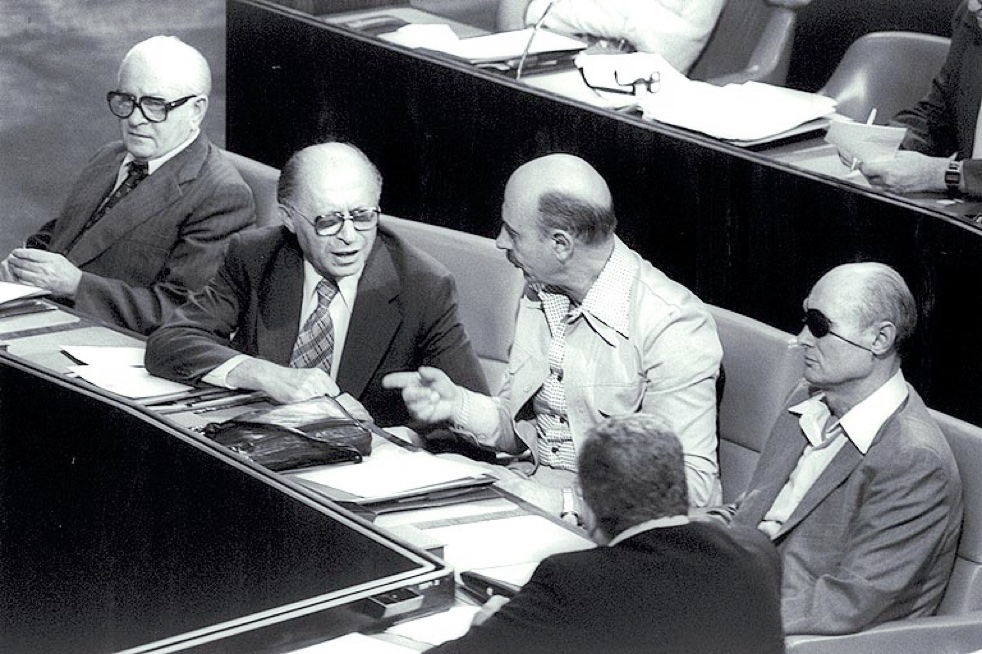

In Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan’s opening remarks explaining the Camp David Accords he omitted telling the parliament that President Carter did in fact apply considerable pressure to Israel, especially during the last two days of the Camp David negotiations. Dayan played down U.S. pressure to win over Knesset votes in favor of the Camp David Accords. Here at the Knesset, however, Dayan’s position was clear. He told his fellow members they could turn the agreements into a “basis for negotiations for peace with Egypt or into a worthless piece of paper.” Dayan asked rhetorically, “We should also ask ourselves whether we are prepared to evacuate 14 settlements and three airfields beyond the border on condition that we get a full peace and after more than a year elapses from the beginning of the implementation of the agreement until those conditions of full normalization — of diplomatic ties, when the withdrawal constitutes half of the territory we should evacuate — are completed.”

Quoting himself from eight years earlier, Dayan said, “We are not talking now of a proposal for an interim agreement, and I can ask myself even sharper questions such as: What has changed from the time when I said we had better have Sharm ash-Shaykh without peace that peace without Sharm ash-Shaykh? …

“At that time I said this, in ‘Abd an-Nasir’s time, I thought just as I said — that the one is preferable to the other. Eight years have elapsed since, and there is a different situation and a different regime. When I look and ask what’s next? What is ahead? I then say that peace without Sharm ash-Shaykh is preferable to Sharm ash-Shaykh without peace if freedom of navigation is guaranteed to Israel. I can cite examples, mine and others, and the question, in each period of time, is whether the issue is realistic. …

“I view the fact that not only the U.S. president signed this as a witness, but also the president of an Arab state as a party, as being extremely important. For all the respect I have for agreements between us and the United States, when we have such an agreement on the issues of no to a Palestinian state, presence of IDF forces and Arab representation of the residents of the territories — an agreement signed by the president of an Arab state together with the U.S. president’s testimony — this is much more important. …

“The Knesset can endorse or refuse to endorse the proposal submitted by the government. If it endorses it I believe that peace negotiations will open and if it does not endorse it, it is possible that in time, when we see, if we see, the developments of unity in the Arab world, the behavior of As-Sadat’s successor, of As-Sadat himself after this proposal is struck off the agenda, of renewed Soviet intervention in the negotiations, we will be sorry that we have not started the peace negotiations under the present conditions — but it will be impossible to do so then, of course.”

— Ken Stein, July 26, 2023

Remarks by Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan at the Knesset About the 1978 Camp David Accords

29 September 1978

Mr. Speaker, honorable Knesset: There was no U.S. pressure on us at Camp David. No one threatened us or hinted that if we did not meet their demands, proposals or views that the United States would reduce its aid to Israel in economic matters, in arms or in political aid. However, we were under pressure at Camp David, the same pressure that we all find ourselves under now. Not President Carter’s pressure; he did not even hint that if we did not achieve a peace agreement we would be viewed as those not prepared to move toward peace.

We were under the same pressure that we are under now: the pressure with ourselves between peace–the desire to achieve peace negotiations with Egypt — and the price that has to be paid for it, between the hope for total peace with normal relations — this is the proposal and I know that there are Knesset members who say that this is not peace; we have never had formal proposals which speak about the normalization of relations as in the proposal for the framework achieved at Camp David — between the proposal for a total settlement and the demand for a total withdrawal, a total withdrawal of the army and a total withdrawal of civilians.

It was said here by Knesset Member Qatan that we came here with a fait accompli. We have not brought faits accomplis. We have brought a recommended proposal. However, it is the Knesset, in its vote, which can turn this proposal into a basis for negotiations for peace with Egypt or into a worthless piece of paper. If the Knesset approves this proposal I believe that there will be a basis for peace negotiations with Egypt. If the Knesset does not approve this proposal another piece of paper will be added to the archives of the various bits of paper. This is what the Knesset has to decide.

The question that we face — that the whole Knesset has to face is if we reject this proposal, what happens next? What will happen tomorrow and the day after, next year and in two years time. What conditions will be more convenient and which conditions will be created that will be better for Israel to be able to achieve peace then. Will it be more comfortable when the whole of the Arab world is united? With the United States and the Soviet Union together, will it be easier for us? Is King Hussein of Jordan becoming more moderate now? King Hussein’s answers now and his rapprochement with Syria — do these show that as the years go by it is becoming easier for us to reach an agreement with him? The possibility of continuing the military government for another 10 years and continuing a state of war for another 10 years and the criticism that is showered upon us by the world, and the major dependence that we have on the United States — will these make things easier for us in the future? Does anyone have the security that the person who will rise in Egypt after As-Sadat will be comfortable for a settlement with Israel than As-Sadat’s predecessor in Egypt? We have gone through these periods.

I remember at the end of the war of liberation in 1948 when Ben-Gurion was prime minister. He was prepared to make a peace agreement on the borders as they existed at the time. This was what could be achieved at the time. The Arabs did not agree to this. They did not agree to anything other than a cease-fire agreement.

However, from a border point of view — when we did not have Jerusalem — Ben-Gurion said this is what we have and if the Arabs are prepared to make peace with us on these borders we will do so.

In 1967, with Prime Minister Eshkol and a national unity government, after we got to the Suez Canal and the Jordan River and we took the Golan Heights — did we not offer the making of peace with a withdrawal from Sinai with security arrangements and freedom of shipping, and a return of the Golan Heights with suitable arrangements to insure the sources of the Jordan River? Did we not offer this? I am neither criticizing nor regretting the fact that when we got a negative answer from Egypt and Syria we decided not to stand idle and wait until they (came?) but established settlements in accordance with various plans on all fronts — on the Golan Heights and in Sinai and in Judaea and Samaria. Standing idly was no way to advance toward peace of toward the achievement of our yearnings.

However, from time to time we said that it was not the settlements that would determine the border if we achieved a peace agreement but that the borderline would determine the settlements, because we were dealing with ourselves. To the best of our minimal military and national considerations — not the desire to expand endlessly — there were differences of opinion in favor or against the Allon plan; there were questions around how far we should settle Sinai; should we settle Nahal Sinai west of Al-‘Arish or be satisfied with the Rafah approaches. No one endlessly sought territory, but this predicament did have one solution: the solution was that we were discussing matters only with ourselves in an effort to consider what the Arabs would agree to. However, we were discussing only with ourselves.

At Camp David we faced a disadvantage and an advantage in the same thing. The disadvantage was what we saw in reality was not similar to our dream and this was also an advantage. The advantage was that what we saw at Camp David was no dream but reality, a concrete proposal. This is the reality that we are now approaching but this is a reality in which there are two sides and not a reality that we have created for ourselves. Egypt is not the only country and was not the first country prepared to make a total peace with us. Jordan — especially in the past two years — the Jordanian government has said that it is prepared to reach a full peace agreement with us. This happened during the Rabin government and, if I am not mistaken, during the days of the Meir government. There were lengthy deliberations with the Jordanian government which lasted for a long time and the Rabin government did not reach agreement with them.

If I may make a side remark here; when we did not manage to influence the Jordanian government into accepting our concept — the Allon Plan, let us say — we did not denigrate ourselves and did not call that government unsuccessful, worthless and gauche because Jordan did not accept our proposals. I did not hear anybody say that had he conducted the negotiations he would have convinced King Hussein to accept Allon’s plan.

We said — and this was the truth — that what we want is unacceptable to the Jordanian government and what it proposes we are not prepared to accept. That was not a question of capability, errors, incapability or all those terms of left handedness and numerous, continuous mistakes, of, let us do it better. This may be done better. However, there is a large gap between the Arab concept prevailing in each Arab country and what we want, and not only what we want — when the United States, in the framework of those proposals of ours and in order to help the two parties to find a way out of the conflict, proposed that a U.S., not an Israeli, air base be set up to replace the ‘Eytam airfield, Egypt did not agree to this.

Not only did it refuse us but it also refused the United States, even though we viewed this as an opening for a political settlement that could have answered some of our wishes. Egypt repeatedly rejected this despite the personal appeals of President Carter to President as-Sadat. With my own ears I heard Carter turn to him and say again and again: Agree to this since this will solve many things. They refused the Americans because of their concept.

We cannot but ask ourselves whether we are prepared to pay this price or to refuse to pay it, and in that case, what will happen in the future, in five or 10 years? Will most of the agreements we will reach with the Arabs be the results of war, with a sword put to the neck? Most of our agreements with the Arabs to date have been like that — in 1948, in 1967, after the Yom Kippur War with the disengagement of forces — with the sword laid to their neck, our army mobilized and the agreements being a result of war.

For the first time now an agreement is discussed without the pressure of the sword laid to the neck and not as a result of war. Do we really want to wait for the possibility of future negotiations stemming from a war, a war that we will win, but a war nevertheless? Will the chances of a settlement be better then than now?

We should also ask ourselves whether we are prepared to evacuate 14 settlements and three airfields beyond the border on condition that we get a full peace and after more than a year elapses from the beginning of the implementation of the agreement until those conditions of full normalization — of diplomatic ties, when the withdrawal constitutes half of the territory we should evacuate — are completed. We are either prepared for this or we way that we are not ready to evacuate 14 settlements and three airfields beyond the border even if this is connected to a full peace agreement with Egypt. Then we will have to ask ourselves, what is a better goal we should seek in the foreseeable future?

When we learned of the Jordanian demand for a full peace agreement — I am neither surprised nor disapprove that the various governments did not bring the Jordanian proposals to the Knesset’s decision, while non, I together with the other cabinet members, recommend that this issue be decided in the Knesset. It is not that we should listed to every Arab proposal that may be raised and say: We shall see and decide on way or the other. …

(MK Yigal Allon) In light of remarks that you have just made — why did you vote against the interim agreement with Egypt in the Knesset in 1975?

(Dayan) I did so because that interim agreement did not give peace. We gave it in return for nothing, do you know why, Yigal, if I may address you as Yigal? It is because of the very reasons that moved you to refuse to sign that interim agreement at the beginning. You later changed your mind and decided to sign it.

(Indistinct interjections) Well, you asked one question, and it is possible the answer does not satisfy you. Do you at least accept that that was not a proposal for a peace settlement but for an interim agreement?

(Interjection apparently by MK Aharon Yadlin to the effect that there was not a total withdrawal and that it was a bilateral discussion not against the background of war but during a state of peace.)

(Dayan) We are not talking now of a proposal for an interim agreement, and I can ask myself even sharper questions such as: What has changed from the time when I said we had better have Sharm ash-Shaykh without peace that peace without Sharm ash-Shaykh?

At that time I said this, in ‘Abd an-Nasir’s time, I thought just as I said–that the one is preferable to the other. Eight years have elapsed since and there is a different situation and a different regime. When I look and ask what’s next? What is ahead? I then say that peace without Sharm ash-Shaykh is preferable to Sharm ash-Shaykh without peace if freedom of navigation is guarantee to Israel. I can cite examples, mine and others, and the question, in each period of time, is whether the issue is realistic.

I want to go back for a moment to the questions of the eastern and southern fronts. I want to say why, also in the event Jordan proposes to us a full peace under conditions it is raising today, I do not recommend that we discuss this. How do we, and should we, examine this? First, where will the proposed Arab agreement take us? To which border — to the border between Kfar Saba and Qalqilyah? This is demanded by King Hussein. Or to the international border between Gaza and Eilat? Will it bring us to security arrangements — the possible security arrangements described by the defense minister here — in the Sinai, or to impossible security arrangements when the Arabs refuse even to accept the Allon Plan in Judaea and Samaria? In addition, another, a less concrete question — when we withdraw, in which land should we be ready to become foreigners and in which land not?

I am prepared to be a foreigner in the Sinai and do not desire to be one in Judaea and Samaria. I am not at odds with the position of the Rabin government that did not bring Hussein’s plan to the Knesset for a decision, nor do I criticize those who conducted the negotiations for not succeeding in convincing the Jordanian king to accept the Allon Plan. He adhered to his positions and was not amenable to being influenced.

The question facing us now is whether this agreement can constitute, under the present circumstances, an appropriate basis which we should endorse.

Finally, I would like to touch on a question raised by MK Rabin regarding the agreements or understanding with the United States connected with these peace accords. It is not true that the agreement we are now presenting, an agreement which is also connected with another agreement called the working paper and achieved between us and the United States in October 1977, does not include clauses of agreement and commitment between us and the United States or agreement to and understanding of our position on the part of the United States — primarily and foremost, the question of the Palestinian state. Furthermore, in the U.S.-Israeli working paper of October 1977 we find the clear distinction stating that peace agreements will be between Israel and Jordan, Israel and Egypt, Israel and Syria, and Israel and Lebanon, while the issues of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip will be discussed with the Arab residents of the territories.

In the agreement submitted to the Knesset now the question of yes or no to a Palestinian state is linked to the question of a peace treaty and borders. It is most clearly stated in this agreement that what is now being done with the Arabs of the territories, with the representatives of the residents of Judaea and Samaria and the Gaza Strip — and only with them — is not a peace agreement and the borders on the basis of 242. It is not only Prime Minister Begin and President as-Sadat who signed this agreement but also President Carter, as a witness. There cannot be a more precise definition for the lack of intention to view the Arabs of the territories or these territories as a state — when peace agreements and borders should be determined only with Jordan, and the Palestinians can of course join the Jordanian delegation.

The same applies to IDF forces. It is indeed the five-year transitional period that is primarily and foremost talked of now. However, regarding these five years, it is for the first time, and with those signatures and with that testimony of the U.S. President, determined that the IDF forces will withdraw and redeploy in the areas of Judaea, Samaria and the Gaza Strip, or, in English, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

There is no fear and no room for the assumption that what is being talked of is presence in closed camps. Among the various clauses, not to mention our discussions and our map scrutinies, we also find the clause talking of joint Israeli-Jordanian patrols for the safeguarding of the border — not of sitting in camps, but joint patrols, both Israeli and Jordanian border police along the Israeli-Jordanian border. These three points then: A. We talk of Arab representation for the residents of the territories only; B. When we speak of an agreement with a state we are speaking of Jordan — and it is only with it that we talk of borders based on Resolution 242, and the Arabs of the territories can join the Jordanian delegation; C. Presence of IDF forces in these territories during the five-year period and maybe also beyond this.

I view the fact that not only the U.S. president signed this as a witness but also the president of an Arab state as a party, as being extremely important. For all the respect I have for agreements between us and the United States, when we have such an agreement on the issues of no to a Palestinian state, presence of IDF forces and Arab representation of the residents of the territories — an agreement signed by the president of an Arab state together with the U.S. president’s testimony — this is much more important.

The Knesset can endorse or refuse to endorse the proposal submitted by the government. If it endorses it I believe that peace negotiations will open and if it does not endorse it, it is possible that in time, when we see, if we see, the developments of unity in the Arab world, the behavior of As-Sadat’s successor, of As-Sadat himself after this proposal is struck off the agenda, of renewed Soviet intervention in the negotiations, we will be sorry that we have not started the peace negotiations under the present conditions — but it will be impossible to do so then, of course.