Transcripts of interviews with history makers and witnesses

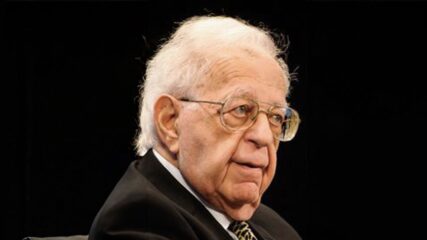

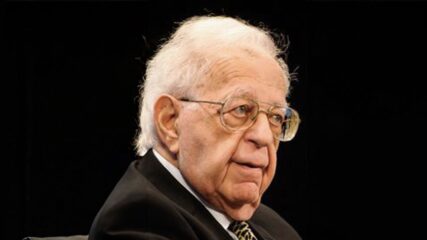

July 16, 1992 Ken Stein Interview with Ambassador Roy Atherton, Washington, D.C., July 16, 1992 Alfred Roy Atherton Jr. participated in U.S-Soviet Middle East negotiations and formulation of the Rogers Plan, 1969; Kissinger-Ismail secret meeting…

Serving as director general of the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1976-1977, Avineri recounts Romanian overtures to Rabin for a visit to gauge interest in another agreement with Egypt. He estimates that Rabin and Begin both took strategic considerations in hand in negotiating; he is highly critical of Carter’s political naivete.

In the 1975-1979 period, Hanan Bar-On served in the Israeli Embassy in Washington and then for seven years as director general of the Foreign Ministry. His insights highlight the building strain that evolved between Jimmy Carter and Menachem Begin. From an Israeli viewpoint, he recalls how unpredictable Zbigniew Brzezinski behaved toward the Israelis, how flexible Moshe Dayan was in seeking compromises, and how the Leeds Castle foreign minister talks in England in July 1978 established the contours for the successful Camp David negotiations two months later. He sheds important light on the context of the four Egyptian-Israeli agreements: Sinai I (1974), Sinai II (1975), the Camp David Accords (1978) and the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty (1979).

Tahsin Bashir served as spokesman for Egypt and for the Arab League in many capacities from 1963 to 1978. He knew Anwar Sadat intimately, revealing that Sadat kept his own counsel while using others to test political and diplomatic options. His long-term goal was to reorient Egypt away from Moscow and obtain Sinai’s return. Sadat cleverly managed others, including Kissinger, Carter and his own advisers.

As a longtime confidant of Menachem Begin involved in the Herut party, Eliyahu Ben-Elissar was Israel’s first ambassador to Egypt. He was a staunch supporter of keeping the area of the West Bank — Judea and Samaria — under Israeli control. Later he became Israel’s ambassador to France and then the United States.

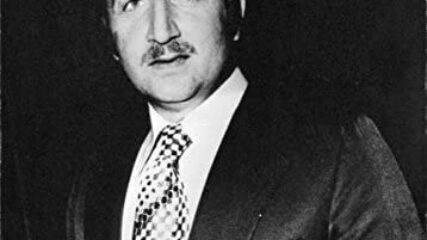

Dinitz focuses on mostly the 1973 October War period, the controversy of delay in the resupply of American military materials to Israel, his relationship with Kissinger and how the US Secretary of State maneuvered the Soviet Union out of postwar diplomacy. He notes that elements of the Israeli army leadership strongly wanted to embarrass Sadat after the war by harming his Israeli surrounded Egyptian Third Army. In the end Israel’s political leadership allowed diplomacy to unfold. Dinitz has great praise for Egyptian President, Anwar Sadat.

Hermann Eilts played a pivotal role in representing the U.S. to Egypt and vice versa in the vital 1973-1980 period when Egypt embraced Washington and turned away from Moscow, and made peace with Israel. Eilts knew Egyptian President Sadat as well as any American official in the period. He provides rich detail and vivid insights into Sadat’s often mercurial decision-making.

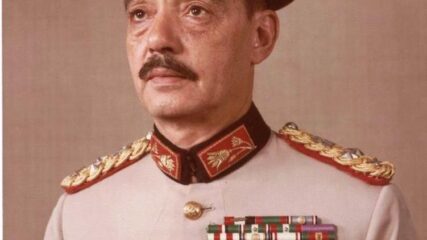

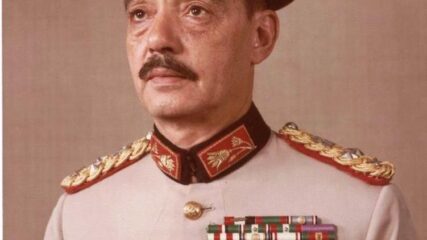

General Ghani el-Gamasy served as Egypt’s chief of staff during the October 1973 war, executed Egypt’s limited success across the Suez Canal, and negotiated with an Israeli counterpart, General Aharon Yariv, the details of the Kissinger-choreographed Kilometer 101 talks, which led to the January 1974 Egyptian-Israeli Disengagement Agreement. Gamasy was surprised when Sadat told him at Aswan then, “Egypt was making peace with the United States and not with Israel.” Gamasy to Yariv, “We (the Egyptians) are finished with the Palestinians.”

A life-long Israeli civil servant, Epi Evron was deeply engaged with Kissinger, Sadat, Meir, Rabin, Carter, Begin and others, as Egyptian-Israeli negotiations unfolded in the 1970s. One will find crisp in his interview insightful assessments of personalities, decision-making processes, and colorful vignettes.

Mordechai Gazit served as Director General in Prime Minister Golda Meir’s office from March 1973 to her resignation in April 1974. He observed the outbreak of the October 1973 War and Henry Kissinger’s diplomatic choreography as it unfolded thereafter. Gazit suggests that he was the source of Israeli and Egyptian generals to negotiate face to face at the end of the war near Kilometer 101.

Ashraf Ghorbal represented Egypt to the US for four years from 1968 to 1972 until Egypt restored diplomatic relations with the US in the wake of the October War. Ghorbal was Sadat’s Ambassador in Washington for 11 years until 1984. He credits Sadat with foresight in setting out and fulfilling his diplomatic objectives; breaking from the USSR, aligning Cairo with the US, harnessing US diplomacy under Kissinger and Carter to secure Sinai’s return to Egyptian sovereignty, and even if that meant signing agreements and recognizing Israel.

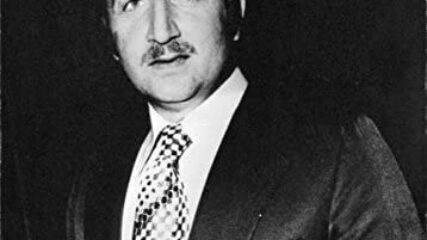

Hafez Ismail was a close adviser to Egyptian President Anwar Sadat. Ismail carried out secret negotiations with Henry Kissinger before the 1973 war to see if the U.S. would quietly start talks with the Israelis. Kissinger said no. Ismail provides notable insights into Sadat’s sophisticated decision-making.

From 1970 to 1984, Khaddam served as Syria’s foreign minister, and later he was Syria’s decision-maker for actions in Lebanon. He recounts Syrian anger toward Egyptian President Sadat’s slow but continual bilateral engagement and recognition of Israel. He recalls how Syrian President Assad, after a four-hour meeting, refused Henry Kissinger’s invitation to attend the 1973 Geneva peace conference, not wanting to sanction the closeness Sadat was establishing with Israel and with Washington. These were the same reasons why Syria refused President Carter’s invitation to attend a similar Middle East peace conference in 1977. Khaddam says, “We were shocked by Sadat’s actions.”

Mustafa Khalil served as the primary Egyptian negotiator in tying up the Egyptian-Israeli treaty with Israeli Foreign Minister Moshe Dayan between September 1978 and March 1979. Though most of the talks took place in Washington, the final excruciating details were negotiated in difficult exchanges in Jerusalem between Jimmy Carter and Menachem Begin in the week before the March 26, 1979, treaty signing.

Mordechai Kidron served in the Israeli Foreign Ministry during and after the October 1973 War. He touched on the war, its aftermath and the unfolding of the Sinai I – Egyptian-Israeli military negotiations and short military talks that took place after the war. He thought that the December 1973 Geneva conference was going to be a long process, not knowing that the conference was stage managed by Kissinger, Sadat, and Meir. Meir was deeply emotional about having Israeli POW’s returned. He notes that Foreign Minister Abba Eban, whom he called an optimist … “was not really altogether founded in reality.”

October 29, 1992 After learning Hebrew, David Korn rose to become chief of the political section while at the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv (1968 to mid-1971). Later, he was office director for northern Arab…

For years, Naftali Lau-Lavie worked closely with Moshe Dayan. His remarks here focus on Dayan as Menachem Begin’s foreign minister (1977-1979). He provides sumptuous detail on Dayan’s thinking and interactions with the Carter administration as it tried to force a Palestinian/PLO state on Israel in seeking a comprehensive Middle East peace.

From 1974 – 1981, Dan Pattir served as advisor on media and public affairs for Prime Ministers Yitzhak Rabin and Menachem Begin. Prior to working for two Prime Ministers, he Pattir worked in the Israeli media, and here he recalls in detail how Kissinger maneuvered the Geneva 1973 conference to keep the Soviets out of decision-making. Likewise he was intimate with the negotiating details and personal relationships that unfolded between Egypt and Israel in that period, especially 1977-1979 including his rendition of the September 1978 Camp David negotiations. Pattir concluded that the Carter administration, no matter how long it earnestly tried, it failed to grasp that neither Egypt nor Israel, were going to allow other Arab states or the Palestinian issue to interfere with their eagerly sought mutually beneficial bilateral agreement, before, during or after Camp David.

Gideon Rafael’s contributions to Israeli diplomacy spanned four decades. His recollections are from the 1930s, the end of the 1947-1949 war, unfolding events before the June 1967 war, and his clear

criticisms of his government’s insufficient response to Sadat’s negotiating overtures to Israel prior to the 1973 War. His life long conclusion: he had hoped that diplomacy would have worked better than it actually did.

Jordanian Prime Minister Zaid Rifai lucidly explains Jordan’s role (inclusion and exclusion) in regional politics from before the 1973 October war to the late 1980s. His insights into Kissinger’s diplomacy and Arafat’s unfounded fear of being absorbed by Jordan are as worthy as they are insightful.

June 10, 1992 (Permission to publish this interview granted by Peter Rodman, June 1992) Peter Rodman, member of United States National Security Council Staff and Special Assistant to Henry Kissinger and Brent Scowcroft, August 1969…

Moshe Sasson spanned four decades in his service to Israel, from the Haganah’s Arab Department of Intelligence in the 1940s to being Israel’s Ambassador to Egypt in the 1980s. He recollects analytically and in detail his conversations with Arab leaders at Lausanne as well as personal impressions of Moshe Dayan and Anwar Sadat. A tour de force.

From 1961 until the early 1980s, Harold Saunders was a key US State Department bureaucrat, an enormously capable word-smith. He had his hand in drafting the 1974-1975 ARab-Israeli Disengagement Agreements, Camp David Accords and E-I Treaty. His memory for detail enabled consequential decision-makers to understand the historical context of events and ideas such as ‘land for peace,’ ‘territorial integrity,’ ‘legitimate rights,’ and a myriad of diplomatic promises made spanning multiple presidencies.

Omar Sirry provides intimate details of the diplomatic aftermath of the October 1973 War, the Kilometer 101 talks, Kissinger’s choreography of the December 1973 Middle East peace conference, and admiration for Sadat as the “modern Egyptian Pharaoh” who was not ever politically passive but took repeated initiatives for Egypt’s benefit.