Arik Rudnitzky, Israel Democracy institute, February 26, 2020

With permission, read full article at Israel Democracy Institute.

Election rallies for the Arab parties in Israel rarely garner much attention or excitement. But recent policy proposals engineered thousands of miles away may have re-energized a once stagnant and unreliable voting bloc.

The peaceful Arab village of Bartaa, home to about 4,500 residents, is located in the northern Triangle region, not far from the city of Umm al-Fahm. The inhabitants are all Muslim; most of them are members of the Kabha family. Despite its relatively remote location away from the main road that connects the coastal plain of Israel with the northern valleys and the Galilee, the peaceful village attracts many Israelis for shopping. The local street market offers visitors local goods and handmade food.

Several days ago, the Joint List — a union of four disparate Arab-Israeli parties that advocates for that minority’s rights in Israel, as well as Palestinian statehood — held an election rally in Bartaa. As a rule, few people bother to show up for these events — after a year of a political stalemate, and after two elections, people are worn out and are showing less interest in the campaign. But at this rally, things were different because of President Donald Trump’s “Deal of the Century” and his idea that the Triangle should be annexed into the future Palestinian state.

The Triangle, whose population currently exceeds 300,000, was annexed to Israel as part of the 1949 armistice agreements. All of its Arab residents hold Israeli citizenship. The idea of annexing the Triangle to a future Palestinian state spurred fierce anger there and triggered a wave of popular protest in Arab localities all over the country. Two weeks ago, there was a mass protest rally in Baqa al-Gharbiyya, one of the largest towns in the Triangle, with more than 30,000 inhabitants. Thousands from all over the country — Arabs and Jews — turned out.

The story of Bartaa is the story of the Arab-Israeli conflict. The armistice agreement signed by Israel and Jordan in 1949 drew the border between the two countries down the wadi in the center of the village. Bartaa was split in two: Half was annexed to Israel, with its residents holding Israeli citizenship, and the other half remained in the West Bank. Until 1967, Jordan controlled the village until 1967, later it came under Israeli military rule and since the mid-1990s has been under the Palestinian Authority.

As the years passed, the economic disparities between the two parts of the village became more and more conspicuous: The villagers on the Israeli side enjoy a higher standard of living.

The residents of “Israeli Bartaa” did not pour out into the streets to protest the Deal of the Century, but neither did they conceal their anger — and even more so, their fear and concern — at the possibility that their homes would be made part of the Palestinian state. Despite all the criticism of the Jewish character of the state, life under Israeli rule is more stable and far better from an economic standpoint. Annexation by a State of Palestine, where there is no political stability or full territorial sovereignty, could make their lives hell. So as far as they — and all the residents of the Triangle — are concerned, the idea of annexation is a nonstarter.

Over the past two decades, there have been proposals to annex the Triangle to the future Palestinian state as part of the final agreement between Israel and the Palestinians. These proposals were authored by Jewish Knesset members, among whom the most prominent is Avigdor Liberman, the chair of the Yisrael Beitenu party. He has floated the proposal several times over the past 10 years. This time it is part of Trump’s plan. It became the talk of the day on the Arab street, not only because of its controversial content, but also because it surfaced in the midst of an Israeli election campaign.

Over the past two decades, Arab parties have found it more difficult to attract the public to their political battles, as they succeeded in doing in the 1970s through the 1990s. In the period between Land Day (March 1976) and the outbreak of the second intifada (October 2000), Arab parties often organized popular rallies and general strikes in protest of discriminatory government policies. In a period in which individualism has come to overshadow collective values, Arab citizens are looking for political results here and now. They may hold the Arab parties in high esteem, but believe that solutions to their problems are more likely to come from nonpartisan civil society organizations.

At the level of local government as well — one of the most important sources of services for citizens — the parties have become weaker. According to Mohammed Khlaile and Amir Fakhoury, writing in Kull al-Arab in January, fewer than 25% of the members of Arab local councils today are identified with a political party.

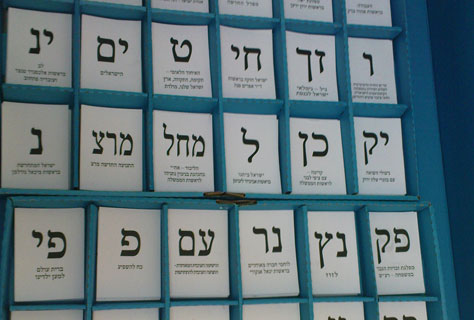

In response to the wishes of their constituency, the Arab parties re-established the Joint List before the September elections, and the Arab turnout rate jumped from 49% in April to 59% in September. But the trigger that will lead the Arabs to flock to the polls next month is located outside the realm of Arab politics. As demonstrated in the past couple of months, developments in the wider political arena in Israel create the real change in the election campaign.

In September, it was Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his anti-Arab campaign that brought Arab voters to the polls in order to challenge his remarks. Next week, it may be Donald Trump’s Deal of the Century that does the trick.

In the coming elections, the turnout among Triangle residents will be at the center of public attention. There is no doubt that the proposal to annex the Triangle to a Palestinian state will provide them with an incentive to vote so as to demonstrate that they are not going to give up their Israeli citizenship.

The article was first published in the JTA.