David Makovsky, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, February 4, 2020

With permission, read full article at Washington Institute.

If the latest U.S. effort winds up backing the Palestinians into a territorial corner from the outset, then Washington may not be able to move the process any closer to direct negotiations.

The newly released U.S. peace plan marks a very significant shift in favor of the current Israeli government’s view, especially when compared to three past U.S. initiatives: (1) the Clinton Parameters of December 2000, (2) Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice’s “Annapolis Process” of 2007-2008, and (3) Secretary of State John Kerry’s 2013-2014 initiative. The message is clear: the Trump administration will no longer keep sweetening the deal with every Palestinian refusal, a criticism some have aimed at previous U.S. efforts.

Yet the new plan raises worrisome questions of its own. Will its provisions prove so disadvantageous to the proposed Palestinian state that they cannot serve as the basis for further negotiations? And would such overreach enable Palestinian Authority president Mahmoud Abbas to sway Arab states who have signaled that they want to give the proposal a chance, convincing them to oppose it instead? If so, the plan may wind up perpetuating the current diplomatic impasse and setting the stage for a one-state reality that runs counter to Israel’s identity as a Jewish, democratic state.

This two-part PolicyWatch will address these questions by examining how the Trump plan compares to past U.S. initiatives when it comes to the conflict’s five core final-status issues. Part 1 focuses on two of these issues: borders and Jerusalem. Part 2 examines security, refugees, and narrative issues.

BORDERS

Is the Green Line still the basis for territorial calculations? The previous three peace deals made the Green Line (i.e., the pre-1967 boundary) the basis of calculations, and proposed that the Palestinians net anywhere from 97% of the West Bank (in the Clinton Parameters) to roughly 100%. These figures would have been reached via “land swaps”—Israel would have annexed some settlement blocs where most Israeli settlers live, largely (but not exclusively) adjacent to the Green Line and inside the West Bank security barrier; in return, it would have given the Palestinians equivalent amounts of land from Israel’s side of the Green Line. During the Annapolis Process, Prime Minister Ehud Olmert accepted the idea of a nearly 1:1 swap, with Israel annexing anywhere from 5.8 to 6.1% of the West Bank but swapping 0.5% less Israeli territory. During the Kerry initiative, the PA was counting on better terms, but the talks did not reach that point.

The Trump plan does not use the Green Line as a reference point at all, so the idea of a 1:1 swap based on that boundary is now moot. Swaps are mentioned in the plan, but they are not equivalent, and they would involve Israel gaining numerous additional areas further inside the West Bank.

It is important to note, however, that the Trump administration has described these as “conceptual borders” whose details can be negotiated, meaning the PA can propose alternatives. The president’s approach to this type of dealmaking is often designed to begin with the toughest position and move toward the middle.

How much of the West Bank? As will be shown in the revised Washington Institute interactive mapping project Settlements and Solutions, the Trump plan proposes a Palestinian state that incorporates about 67% of the West Bank (i.e., 3,907 of its 5,834 square kilometers). This figure increases to nearly 71% when one adds 259 square kilometers of proposed swap areas from Israel adjacent to the West Bank. Specifically, the Palestinian state would include three Israeli Arab communities in the northwest region called the Triangle: Arara, Umm al-Fahm, and Baka al-Gharbiya, all adjacent to the West Bank.

The Trump plan acknowledges that swapping this area requires consent of “the parties”—a vague formulation that presumably means Israel and the Palestinians, but fails to mention the approximately 109,000 Israeli Arabs who live in these three communities. In the days since the plan’s release, Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu has stated that he is not considering this option, apparently fearing Arab backlash at home and abroad on the eve of Israel’s election.

In total, the Palestinians would receive 83% of the combined territories. This means 5,152 of the 6,195 square kilometers comprising the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, the northern quadrant of the Dead Sea, half of the “No Man’s Land” near Jerusalem, and swap areas.

Point of territorial departure? The point of departure for the Trump plan is that no Israeli settlers or Palestinians are to be forced from their homes. This means that all 449,000 Israeli settlers living in 128 West Bank settlements would stay where they are. Fifteen of the settlements containing approximately 14,000 people would exist as separate enclaves in a Palestinian state, with a temporary four-year freeze on their outward expansion while the Palestinians consider their response to the U.S. plan.

The contrast with past initiatives is dramatic. Until now, it was assumed that Israel’s primary gains would focus on the blocs located in the vicinity of the Green Line and the security barrier, meaning 51 settlements that take up 8% of the West Bank and are home to 345,000 settlers (or 77% of the total settler population). When one factors in East Jerusalem, the figure goes up to approximately 660,000 Israelis (or 85% of all affected Israelis) in virtually the same amount of land (Israel has not counted East Jerusalem residents as settlers ever since it annexed the city).

Under the Trump plan, however, Israel would also annex the non-bloc settlements scattered further away from the Green Line—in all, an additional 77 settlements that lie outside the security barrier and contain 104,000 Israelis. In addition to producing a deeply fragmented Palestinian state, this proposal would increase Israel’s total share of the West Bank from 8% to 31%. Moreover, 3% of the Palestinian population would still be living under Israeli sovereignty, including the communities of Bani Naim, Qibya, Rantis, Shuqba, Kafr Qaddum, Hajja, and Immatin.

To illustrate these proposals, the administration has also released a “Conceptual Map.” The U.S. government did not publicly release a map with the previous peace plans, believing that such territorial specifics were up to the parties to negotiate. At the January 28 White House unveiling ceremony, President Trump stated that Netanyahu had put forward the current map—the first time any Likud Party leader has taken that step. During the Kerry initiative, Netanyahu saw any map as political dynamite that could alienate settlers in his coalition, particularly those who lived outside the proposed borders. He likely believes that the inclusion of a map this time around is offset by the plan’s stated principle that no one will be moved from their homes.

Changes in the Jordan Valley? In former rounds of peacemaking, Israel has emphasized its desire to maintain security control of the border with Jordan, not only to prevent the smuggling of materiel and personnel, but also due to strategic concerns stemming from the military attacks it faced on that front in the 1948 and 1967 wars. Past U.S. administrations assumed Israel would never agree to Palestinians manning that frontier—the Clinton and Annapolis efforts focused on multinational forces playing that role, while the Kerry effort proposed U.S. troops. The Trump approach goes further, giving Israel full sovereignty over most of the Jordan Valley. This would deny the Palestinians any border with Jordan, meaning Israel would effectively encircle the new state and determine who enters and leaves.

JERUSALEM

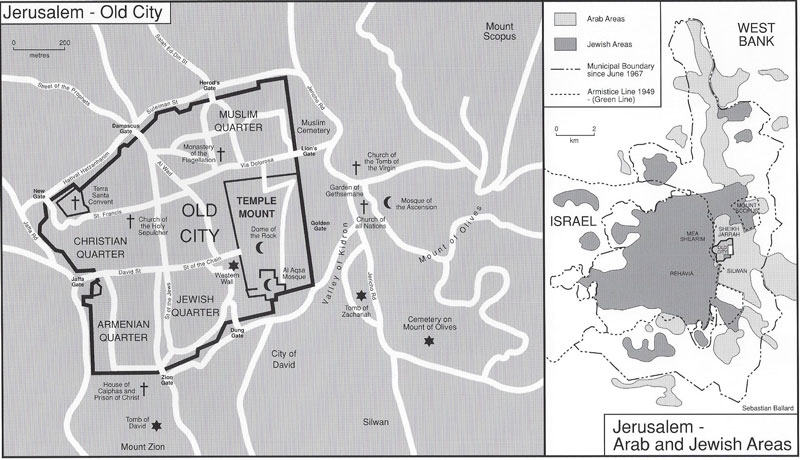

Geographical division and political status. Like previous U.S. initiatives, the Trump plan envisions Jerusalem as a geographically undivided city. Past plans largely focused on the idea of a geographically united city with divided sovereignty: Israel would hold sway over Jewish neighborhoods in the area formally known as East Jerusalem, while Arab neighborhoods would become part of the Palestinian state. Yet the details of the Trump plan sharply diverge on the latter issue.

On one hand, the new plan marks the first time the administration has stated that there should be a Palestinian capital inside the northern tip of Israel’s Jerusalem municipal boundary, that the United States would establish a separate embassy in this capital, and that it would encourage other countries to do the same. On the other hand, the plan states that Jerusalem will remain the capital of Israel and that much of the city will be ceded to Israel, noting that “the sovereign capital of the State of Palestine should be in the section of East Jerusalem located in all areas east and north of the existing security barrier, including Kafr Aqab, the eastern part of Shuafat, and Abu Dis” (p. 17). Kafr Aqab and Shuafat (a refugee camp) were among the twenty-eight Palestinian villages incorporated within the Jerusalem municipal boundary when Israel expanded it by 70 square kilometers after the 1967 war. Dubbed “No Man’s Land,” this zone is home to 56,000 Jerusalemite Palestinians and 70,000 West Bank Palestinians outside the security barrier.

In all, the administration’s formulation would give Israel sovereignty over areas of East Jerusalem that are home to approximately 294,000 Palestinians. Some of these individuals live in exclusively Palestinian neighborhoods such as Beit Hanina in the north and Jabal Mukaber in the south, so it is curious that the plan’s conceptual borders do not address this demographic fact. Instead, the plan offers these Palestinians the opportunity to become citizens of Israel or Palestine, or to simply retain their status as permanent residents of Israel.

Holy places. The Trump plan is somewhat vague on the highly sensitive issue of religious sites in Jerusalem. It does not explicitly deal with Israel’s sovereignty, nor does it mention Jordan’s day-to-day administration of Muslim holy sites as outlined in the Israel-Jordan peace treaty. After complimenting Israel for ensuring access to religious sites, the plan states the following:

“We believe that this practice should remain, and that all of Jerusalem’s holy sites should be subject to the same governance regimes that exist today. In particular, the status quo at the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif should continue uninterrupted. Jerusalem’s holy sites should remain open and available for peaceful worshippers and tourists of all faiths. People of every faith should be permitted to pray on the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif in a manner that is fully respectful to their religion, taking into account the times of each religion’s prayers and holidays, as well as other religious factors” (p. 16).

Two takeaways emerge from this passage. First, given President Trump’s intimacy with the Saudi leadership, the Jordanian government feared that the U.S. plan would seek to transfer custodianship of Jerusalem’s religious sites from Amman to Riyadh. This fear proved to be unwarranted. Second, the mention of all faiths being allowed to pray there will be interpreted to include Jews, though U.S. officials seemed to walk back this view after the plan was released.

CONCLUSION

The Trump plan’s parameters on borders and Jerusalem suggest that the administration has moved the U.S. position sharply in the direction of Israel’s current government. In the most hopeful scenario, the combination of a tough new U.S. approach and the initial openness of Arab states to consider the plan as a point of departure could jolt the Palestinians to decide that time is not on their side, perhaps leading the parties to resume talks and find suitable compromises. In a less hopeful scenario, Palestinian anger toward the plan proves too strong to dispel, and unilateral Israeli annexations in the West Bank produce broad international opposition to the plan, essentially ending any near-term prospects of negotiations or a two-state solution.

Abbas seemed isolated in the region prior to the plan’s release, but the February 1 Arab League meeting in Cairo and the February 3 Organization of Islamic Cooperation meeting in Jeddah may have changed that somewhat. Going forward, he may be able to paint the administration’s shift on core issues as American overreach, and silence Arab critics who are fatigued by the longstanding paralysis on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

David Makovsky is the Ziegler Distinguished Fellow at The Washington Institute and creator of the new podcast Decision Points: The U.S.-Israel Relationship.