Go to The Timeline starting at Era I

From the biblical covenants, Jews bound themselves to the belief in one G-d, an unbreakable tie to the Land of Israel. From its inception, Jewish identity was wrapped around the mutual commitments between G-d and the people.

These included living in the land of Israel, G-d’s promise to make of them a ‘great nation,’ giving them a name, and being a blessing for other nations of the earth. For those promises, Jews were required to engage in specific behavior, namely keeping laws, rituals, customs, etc. Knowing Torah (the Bible) and halakhah (the oral tradition that encompassed all aspects of a Jews life) were core elements in Jewish identity. Both originated before the Common Era (BCE). Torah study included educating the young where the importance of Zion, or the land of Israel was affirmed as integral to Jewish identity. In Psalms it is written: “By the waters of Babylon, there we sat down and wept when we remembered Zion.”

Jews evolved as a people based on their laws, their common historical experiences, and because of what others did to them as Jews. After wandering under Moses’ leadership, Jews founded their state, and built their temple as a center from which their beliefs radiated. Then it was destroyed in 586 BCE, rebuilt again, and destroyed again in 70AD. Two Jewish states were established and destroyed. Since their displacement from the land of Israel by the Romans, Jews strove to hold fast to their core belief in monotheism, the Sabbath, and core rules of behavior. Learning Torah, obeying its prescriptions, and staying attached to life-cycle events provided internal communal cement. Through Liturgical References to Zion and Jerusalem, the Jewish people sustained their connection to their ancestral land. Moreover, their religious calendar was determined by the schedule of holidays and fast days as celebrated in Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel). Regardless of whether they lived in Baghdad, Berlin, or Budapest, Jews all read the Torah, maintained their customs and observed their laws, and retained a “longing” to return to Zion.

Wherever they lived, Jews existed as a minority. That repeated demographic reality affected their daily lives and, especially, their interactions with non-Jews. Without established or protected rights and privileges, they regularly suffered physical abuse at the hands of caliphs, church officials, czars, kings, popes, notables, politicians, sultans, theologians, and others. They were routinely punished for their collective perseverance in adhering to their beliefs (many non-Jews called it obstinacy) and for not embracing the majority faiths of Christianity or Islam. It was not uncommon for Jews to be blamed for the killing of Christ, bad economic times, causing plagues and disease. Dying in defense of Jewish practice was not exceptional. In good times Jews were tolerated, in bad times persecuted. More often than not, anxiety and uncertainty characterized Jewish existence. Speculation in Jewish communities always centered on whether the next autocrat would be better or worse than the current one? Dependence for security of life and property rested with the powerful non-Jewish autocrat. When possible, Jews sought and were granted limited rights by a ruler of a region where they lived.

Sometimes these agreements, pacts or charters were mutually negotiated, other times they were simply imposed. These agreements, sometimes in writing and sometimes merely understood, stated the limitations on Jewish civil rights, the professions that Jews could or could not practice, restrictions on where Jews could live, and their ability to own property. For Jews, these understandings with autocrats were all aimed at “buying time” until social and political living conditions improved, and of course sometimes they did not. Within the lifetime of rulers such as Ferdinand and Isabella in Spain at the end of the 1400s, tolerant acceptance swung swiftly to severe persecution. In the case of Spain, after their announced expulsion, Jewish options included forced or volunteer conversion to Catholicism, secretly practicing their Judaism, being killed for refusing to accept edicts against them, or fleeing Spain for other parts of Europe or the Mediterranean region. In the Moslem world as well, Caliphs and Sultans imposed restrictions on Jewish life. Jews endured centuries of precariousness where physical, social, and economic uncertainties loomed as sure as the Sabbath’s arrival at the end of every week. Jews could never undo their minority status, but they looked to minimize their vulnerability.

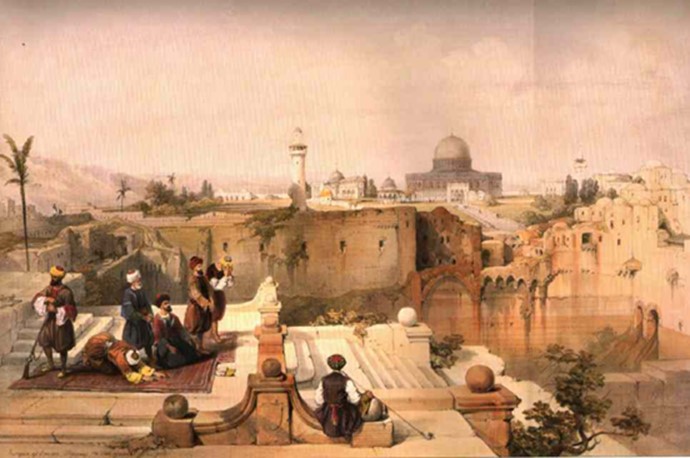

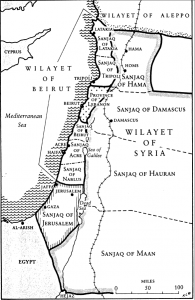

Across western and eastern Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East Jews sustained themselves as communities to survive. They took care of their Jewish life cycle events, educated their own, taxed themselves for communal needs, and made necessary adjustments about daily life without sacrificing core beliefs. For Jews living in the Ottoman Empire, across North Africa and in the Middle East with notable exceptions over time, life was generally more tolerable than western European or eastern European experiences. In Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, Istanbul, Fez, and elsewhere among small and larger Jewish communities in the Ottoman Empire, Jews found themselves highly successful in commerce, having access to education, and sometimes becoming advisers and ministers in Arab and Moslem settings. Many Jews who settled in the areas where Ottoman rule extended, were treated as a tolerated minority, similar to Christians living under under Islam. Jews were permitted to run their own civic affairs, make their own religious judgments, and essentially lived a tolerated existence. In economics and commerce, Jews generally interacted regularly and often successfully with Moslem populations.

Jewish messianism continued to dominate their theology. At its core was the belief that if one continued to practice laws and customs rigorously and without fault according to what G-d had outlined in his covenants, and commandments, then there would be an ‘end of days’ and Jews would return to the land of Israel. That would relieve them of their prolonged exile. The basic question was posed: should Jews continue to wait for the messiah, or me proactive and reach toward what was perceived as a changing world around them?

Life for Jews in Europe continued to be harsh. Habitually barred from many professions, excluded from schools and universities, and forced to live in confined geographic areas in towns, villages, and rural areas was normal. From the mid-1700s forwards, prospects of continued persecution diminished slowly as the period of emancipation unfolded in Europe. The core concept which affected Jews and non-Jews alike was to what degree could individual rights overtake or replace the power of the autocrat. These were core themes found in the American and French Revolutions. Adopting the notion of individual rights imbibed from their surroundings greatly undermined the notion of waiting for divine intervention to alter their precarious existence. Where Jews were exposed to literature and philosophies that argued for individual rights, traditional boundaries of the historically autonomous Jewish community also began to breakdown. This actual shift in politics and political life, away from the hated autocrat who had punished Jewish life and property for centuries and toward promotion of individual rights was of course welcomed by Jews who lived on the social and economic margins. Not surprisingly, Jews evolved expectations that they might be accepted as equals by the non-Jewish world. From the middle of the 1700s forward, Jews in European areas slowly questioned the role Judaism and Jewish practices should play in a modernizing world.

Some answered the question of redefining their Jewish traditions by fashioning or adopting new ideological paths. Reform and Conservative Judaism emerged in response to seeking acceptance by the non-Jewish world; for others it was conversion or total lapse of Jewish practice. Some accepted socialist ideals, maintaining some religious practice, others converted to Christianity. Already in the 1840s, Rabbis Yehuda Alkalai and Zvi Kalischer, independently of one another, suggested that the Jewish condition could be bettered if it were driven by human decisions to resettle in Zion, rather than waiting for divine or messianic intervention.

Alkalai also suggested that Hebrew be used in daily affairs to unite Jews, and not simply be relegated to sacred usage. In places where the concepts of nationalism were known and applied, small groups of Jews spoke about Jewish nationalism, having a Jewish territory, or Zionism as another identity option for Jews to consider.

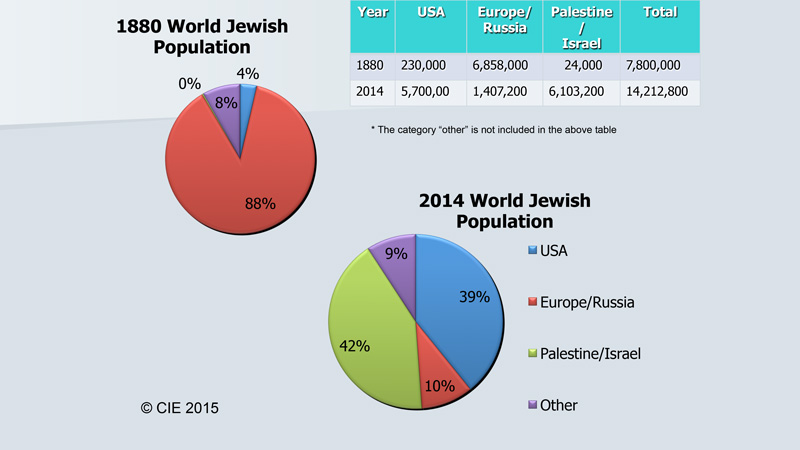

Zionism appealed to those few Jews who had sniffed freedom, sought liberty and security, but wanted it in their own place, Eretz Yisrael. That was a key point of Zionism: Jews no longer wanted to be at the mercy of someone else’s uncertain attitude about Jewish rights. Jews wanted to control their own destiny in their own land. In the 1800s, very few Jews in Middle Eastern lands were sufficiently impassioned with Zionist belief to move to Eretz Yisrael, though a small group of Yemini Jews immigrated at the end of that century. The great majority of Jews who immigrated from Europe to North America in the 18th and 19th centuries paid little attention to the development or support of Zionism. In the middle of the 1800s most Jews lived in non-democratic settings; a century and a half later most Jews were living in democracies where Jewish life was no longer determined by the will and whim of others.

Not surprisingly, Zionism gained faster traction in those places where Jews had been systematically oppressed, where government sanctioned anti-Semitism and violence against Jews was more frequent. In Germany in the 1870s, anti-Semitism took on a racial dimension and in eastern Europe, pogroms, or attacks against Jewish life and property increased in frequency and intensity. Since Jews were often denied civic equality because they practiced their faith openly, many Zionist thinkers, but not all of them, chose secular Jewishness as part of their newly evolving national ethos. Thus, there was frequent dismissal of Talmudic and Rabbinic affinities. Historical references to the bible rather than religious practice became important to for the early Zionists, though a goodly number of orthodox Jews as well embraced the notion of re-establishing a national Jewish presence in Palestine. Some early Zionists sought only a Jewish cultural revival as advocated by Ahad Ha’am, a renewal of Hebrew as a spoken or literary language rather than one of prayer; other Jewish nationalist thinkers wanted their Zionism suffused with socialist ideals. A common thread for all Zionists however, was the quest to renew their identity and practice their future in a Jewish national territory. And yet, no matter how “revolutionary” Zionism was, it was practiced or endorsed by only a tiny sliver of world Jewry.

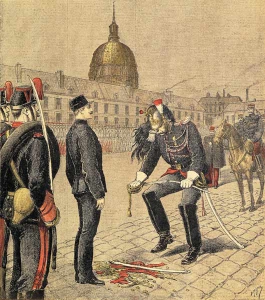

The truly precarious status of Jews, even in liberal countries like France, revealed itself again in the Dreyfus Affair. That unfolding event influenced the Viennese journalist, Theodor Herzl, to write a pamphlet in 1896 (The Jewish State) calling for Jews to eliminate their insecurity by establishing a state of their own. Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish French army captain, was falsely accused and found guilty of providing military secrets to the German Government. Witnessing the trial in liberal France, of all places, Herzl recognized that Jews, like Dreyfus would be insecure wherever they lived. Herzl captured an already existing motif of Jews seeking security and freedom in their own place.

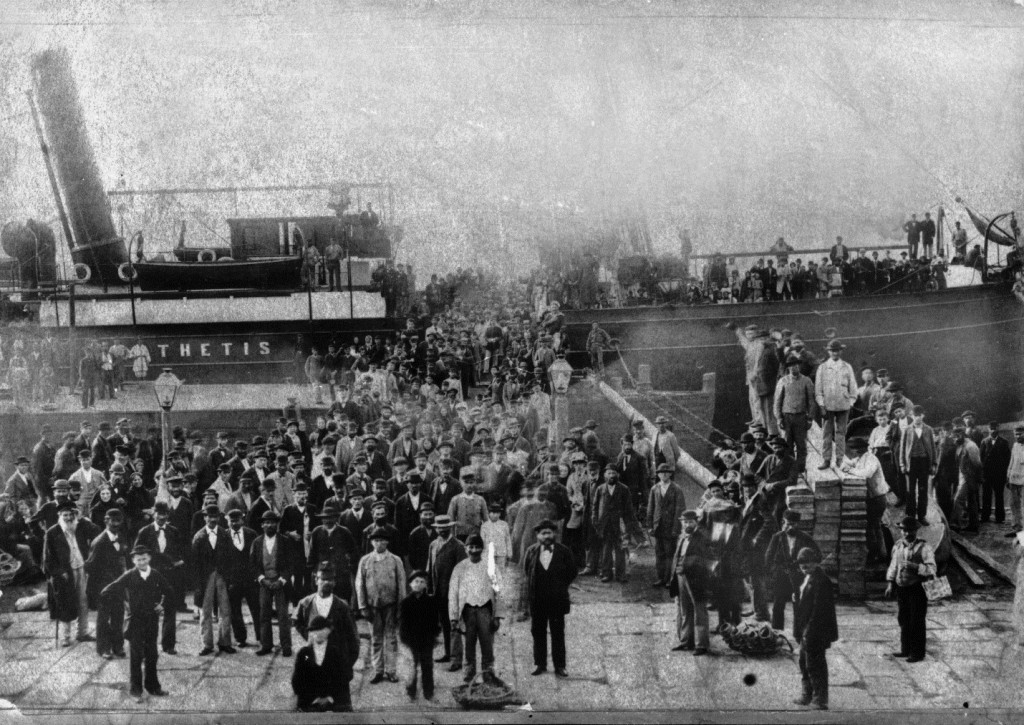

In August 1897, Herzl organized the First Zionist Congress in Basle, Switzerland. More than 200 Zionist delegates from all over the continent brought their varying opinions and energy to the first meeting of the World Zionist Organization (WZO). Already, during the previous two decades, some 15,000 Jews had trickled into Palestine from European and Middle Eastern origins, but unlike Jews visiting Eretz Yisrael before 1882, these new immigrants carried some degree of national political intention. Reinforced by centuries of anti-Semitism and held together by their Judaism, Zionists used their well-formed communal experiences to shape a new way of life. Continuing to negotiate with the politically powerful, Jews no longer focused on securing rights and privileges on someone else’s turf, they engaged in diplomatic negotiations about gaining rights in what they hoped would be their own national homeland. Zionists gradually moved from being powerless to acquiring and exercising political influence.

Initially, Zionists chose one of two methods along their journey to national sovereignty. The first centered on seeking diplomatic permission and physical protection from a Great Power or number of powers. This was political Zionism. The second method centered on simply creating facts. This meant building a place for themselves – immigrating, purchasing land in Eretz Yisrael, and creating Jewish enclaves, villages, and settlements – and asking for permission later from the powers that held influence over the Middle East. This was practical Zionism. Zionists argued amongst themselves about which method was preferred. In the first decades of the 1900s, the two methods gradually merged into a third. Still another strand of Zionism emerged, which wanted to use force to establish and secure Jewish presence in Eretz Ysrael. Differences remained about the definition of Zionism, and its economic, social, political, religious, and philosophical leanings. Its combinations were varied: capitalist, socialist, Marxist, rural, urban, religious or secular.

Without a dominant political stream, the practice of Zionism in Eretz Yisrael remained diverse, often contentious, but always dynamic. Whatever an individual immigrant’s outlook and however it evolved, life in Palestine was not easy, sometimes sufficiently difficult for some who tried Zionism to give it up and emigrate elsewhere. Changing events in the Middle East, Palestine, and Europe during the first two decades of the 20th century greatly influenced the pace of Zionist history, and particularly the ability to link people to the land. Jews who immigrated or helped the Zionist movement evolve, created new institutions to meet immediate needs. Some organizations like the Palestine Colonization Association predated the founding of the WZO; others emerged out of the WZO like the Jewish National Fund, the Palestine Colonial Trust, and the Jaffa/Palestine office of WZO. These organizations and dozens of smaller ones helped Jews catalyze the slow transition to a new way of life in Palestine, and reconstitute a secure a small but vibrant Jewish demographic presence there.