March 25, 2019

Kenneth Stein, the founding president of Emory University’s Center for Israel Education, has taught Middle Eastern history and politics at Emory for 43 years. He spent more than half that time serving as a key advisor to former President Jimmy Carter for his post-White House involvement in the Middle East. Stein resigned in 2006, citing falsehoods in the former president’s bestselling book “Palestine Peace Not Apartheid.”

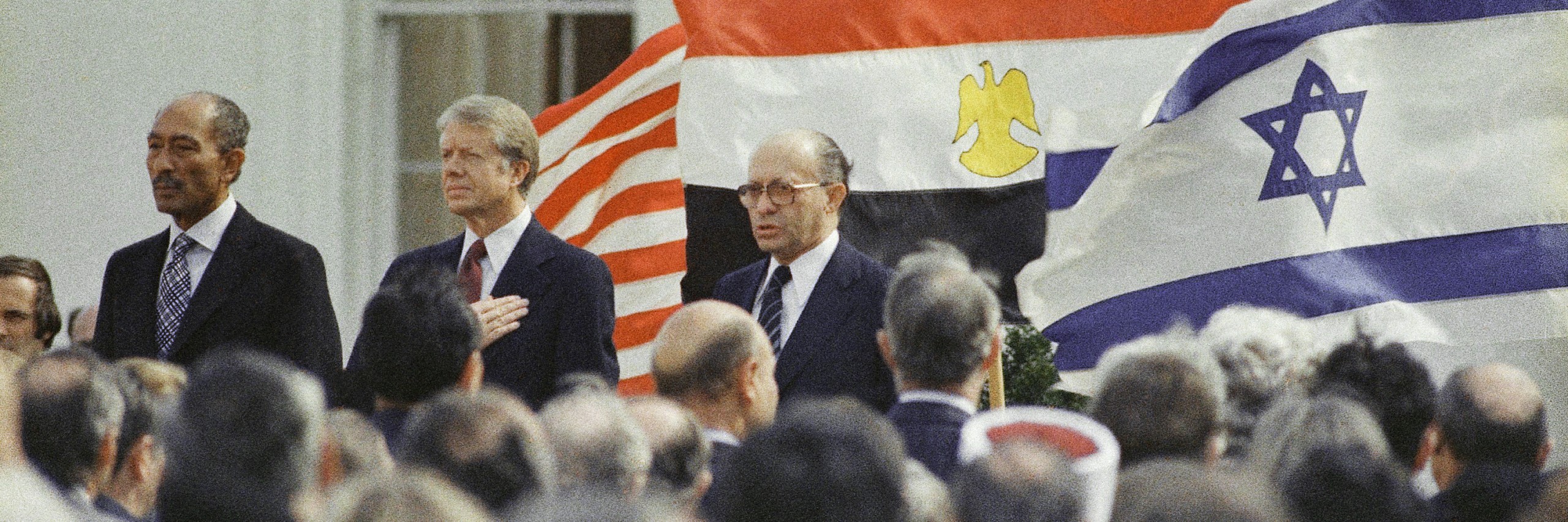

Stein says Carter was vexed that he had mediated only one successful peace agreement during his time in the White House – the Egypt-Israel Peace Treaty. He had hoped it would be a catalyst for comprehensive peace across the region. Regardless, that treaty, signed on March 26, 1979 by late Egyptian president Anwar Sadat and Israeli premier Menachem Begin, was a milestone for peace in the Middle East – the first such peace pact between Israel and an Arab state.

Ahead of the 40th anniversary of the watershed truce, AJC talked to Stein about the impact of that treaty then, now, and going forward.

How did Egypt and Israel reach an agreement?

No. 1: It ended the state of Israel’s belligerency with the region’s most populous Arab country. For Israel, that was a positive result of the negotiations with Egypt. Israel knew that once Egypt was no longer a wheel on the Arab military wagon, the wagon could not move forward. Taking the wheel of that wagon was vital to Israel’s long-term security.

No. 2: The treaty gained for Egypt a return of Egyptian land that Israel had won in the ‘67 war and Israel withdrew all of its settlements from Sinai. So Sadat’s victory was restoration of Egyptian land and removal of Israeli settlements. The trade-off for Begin and Sadat was, if you make a treaty with us, with full diplomatic relations, we will give you back all of Sinai and remove all of our settlers and settlements. Sadat had to recognize the Jewish state, and Begin had to return strategically important land and withdraw settlements, which means taking out settlers.

Why did it work then? Because each leader was willing to engage in a critical trade off, because they knew that their respective countries would be better off with the trade-off. Each of them had the pot sweetened by American foreign aid and assistance. The condition for making the agreement work was each country benefited. You would not have an agreement if only the mediator had wanted an agreement.

Why has the same strategy not worked between Israelis and Palestinians?

There are several reasons. The Palestinians, to reach an agreement, have got to recognize the existence of a Jewish state and end its belligerency with the Jewish state. Palestinians have already recognized Israel. They did that in 1993. But to end the conflict means the PLO has got to give up the retention of its largest constituency – the refugees. Can the PLO give up its No. 1 constituency? So far, the answer is no, they can’t. Or they won’t. You have to be able to bring along your domestic audiences with you if you’re going to succeed. And any PLO leader that does so may face a bullet.

Both Begin and Sadat had domestic constituencies that were not happy with what they were doing, but they had the capacity to bring those constituencies forward.

How much of it has to do with leadership?

Begin relished the idea of being prime minister. He had been dissed, punched, pushed down. He had been relegated to unimportant status by the founder of the state of Israel David Ben-Gurion. Begin wanted desperately to do what Ben-Gurion could never do – reach a peace treaty with an Arab neighbor. He was only going to do it if it was in Israel’s long-term interest.

One of the major reasons it worked between ‘73 and ‘79 was because of Sadat. Sadat was different. Sadat wanted to do something for his country, for his people. He loved the adulation of the crowd. He loved being recognized. He loved being dressed up like he jumped out of Gentleman’s Quarterly. He loved to puff on his pipe. He was a show man. At the end of the day, he knew what was good for his country and his people. Americans and American Jews were spoiled by Sadat, and I think were surprised that Begin was as forthcoming as he was.

I don’t think we knew what we had at the time.

Are the challenges different today?

When you tell this history, you always have to do it with emphasis on context. Because most folks don’t remember what it was then, even those who were alive. Historical context and perspective are very difficult for the modern user of information to have as part of their knowledge bank. Everything is blogs. Everything is instant. Everything is quick. Think about it. We used to read articles and books until someone said ‘You don’t have to read that much. Just write an executive summary.’

Much has happened since 1979 to change the context. Anti-colonialists in the post-World War II are dead. Arab secular nationalism has failed. Islam as a platform for mobilization has expanded, or even exploded. The strength of Arab states is shivering or on the brink of maybe collapse. Insurgents are now part of the Middle East. American dependence on oil from the Middle East is virtually non-existent. The Cold War is over. Settlements got the territories. Twenty or 30 things have changed. And if the environment changes, it has an impact on the willingness of sides to compromise. Each of these items I mentioned all have an impact on whether a Palestinian-Israeli agreement is doable or will even stick.

If the treaty didn’t lead to other peace agreements, did it have an isolated impact?

There’s no shortage of solutions offered by the international community, think tanks and diplomats. There must be dozens of them, many of them we don’t even know about. That’s the one thing the Egyptian-Israel Treaty did. It unfolded a whole series of plans of what to do next. Not just from America, but it came from the Europeans. It came through the Oslo Accords.

The Egyptian-Israeli Treaty has stuck and remains in force because it’s in the interest of both countries. Israel does not want Egypt as an enemy, and Egypt wants a friendly border state to its east. Each of them has other issues on their respective borders that are really troubling. They can each say’ ‘I don’t have an issue with the Egyptian Israeli border, that’s one less border I don’t have to focus attention on.’

Despite this success, where did the Carter administration go wrong?

We made a mistake in the Carter administration thinking we could have comprehensive peace. It just didn’t realize just how much difference there was amongst all the Arabs. Zbigniew Brzezinski (Carter’s national security advisor) acknowledged this. But when they came to office, they were focused on a comprehensive peace. Bring everyone together. Negotiate with rationale and logic. They’ll come to a conclusion, walk away and the lion will lie down with the lamb.

One of the great shortcomings of the Carter administration was its misunderstanding of Arab and Middle Eastern politics. They were interested in transactions and the art of the deal. That’s perfectly legitimate, but transactions that don’t change attitudes, or transactions that exist, but are undermined by mistrust, don’t last.