(24 February 1949)

Printable PDF

United States. Department of State. “General Foreign Policy Series 117.” American Foreign Policy 1950-1955. Department of State Publication

6446. vol 1. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1957. Print.

Israel’s War of Independence ended with the signing of separate armistice agreements between the newly established Jewish state and four Arab states (Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria). However, peace treaties were not signed between Israel and her Arab neighbors, or with the Palestinian Arabs. No international borders were fixed or recognized between Arab States and Israel. On January 12, 1949, on the Island of Rhodes, Egyptian-Israeli armistice talks commenced in the format of proximity talks with Ralph Bunche, the mediator, shuttling messages between floors of the Hotel Roses. These were not official face-to-face talks, but some took place informally. Egyptian-Israeli talks resulted in a signed armistice agreement on February 24, 1949. Similar armistice agreements were signed by Israel with Lebanon on March 23, with Jordan on April 3, and Syria on July 20. Several individual groups of Palestinians met with Israelis to discuss political and economic matters, particularly the release of back assets to Palestinian depositors (a quiet event completed in 1950 and 1951). While Israel achieved official international legitimacy when it was sovereign state and non-acceptance of her territorial integrity officially continued until Egypt became the first Arab state to sign a peace treaty with Israel in March 1979.

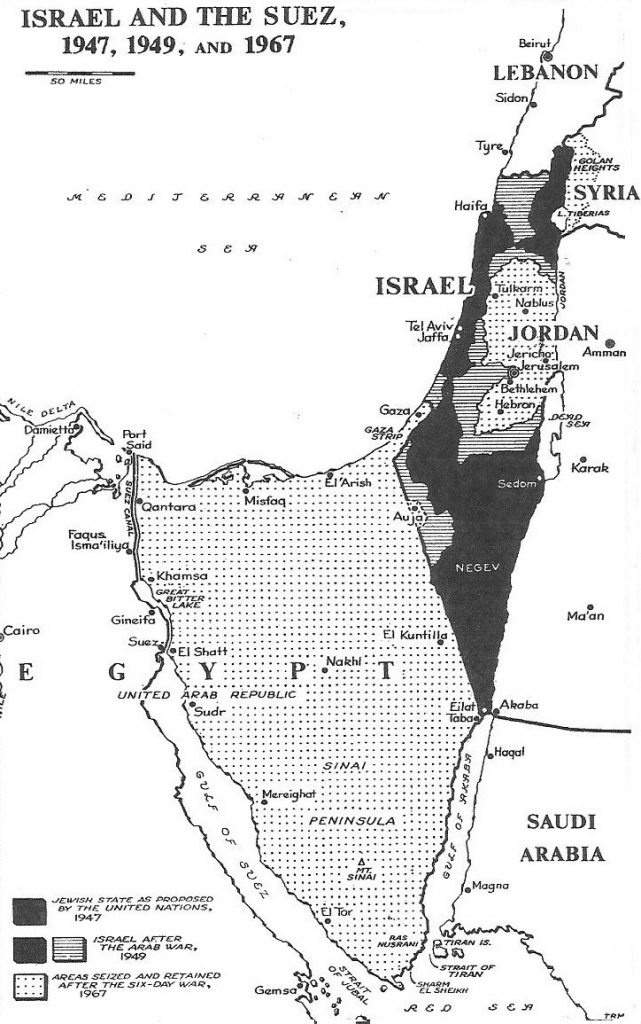

When the 1949 armistice agreements were signed, they affirmed demographic and territorial realities resulting from the war.

In terms of territory, the land that the UN allocated to the Jewish state in the 1947 partition plan was enlarged by 37 per cent, from 14,900 square kilometers to 20,500 square kilometers. Had Arab states accepted the partition plan in 1947 and established an Arab state alongside a Jewish state, not only would an Arab state have been created in Palestine, but the Jewish state would have been more than 5,000 square kilometers smaller than it ultimately ended up being. In terms of demography, during the 1947-1949 conflict more than 700,000 Palestinian Arabs became refugees from different parts of Palestine, settling in Arab states and migrating elsewhere.

Of course, no one knows exactly how many Palestinian Arabs might not have left Palestine if an Arab state was created. For the Palestinian Arabs, their flight was a seminal moment in the shaping of their identity as a community; their passionate desire to return to Palestine became a central part of the Arab-Israeli conflict for the next six decades. As a result of the war, the city of Jerusalem was divided into an Arab sector and Jewish sector, not to be reunited until after the June 1967 war.

The West Bank of the Jordan River was a spoil of war for Jordan’s Emir Abdullah, and he and his long-term successor, King Hussein, controlled it outright or had active influence over it until 1988. The 130 square kilometer Gaza Strip, located in southern Palestine, came under the administration of the Egyptian government until after the June 1967 war. While Jordan and Egypt controlled the West Bank and Gaza areas, neither promoted the establishment of an independent Palestinian state except in 1948-1949, when the “All Palestine Government” was formed for a brief period of time.

For Zionists who had diligently labored since the end of the 19th century to establish a territory where Jews could be free from persecution and determine their own future, the war culminated in the reestablishment of a Jewish state. The Zionists were not handed Palestine by a world guilty for sitting by while six million Jews died in the Holocaust. The armistice ended in favor of the Zionists because they chose to take destiny into their own hands by lobbying great powers and by laboring for seven decades to merge people with land and an economy created by hard work. While they made mistakes along the way, in the end, diverse groups of Zionists chose to fight for self-determination and to bury their profound ideological differences. For a brief period between 1947 and 1949, Zionists pulled together to establish a state. Anti-Semitism in the world certainly did not end because there was now a Jewish state; however, Diaspora Jews were suddenly viewed by non-Jews as a people capable of wielding power and defending their own. These were certainly unintended consequences for Jews not living in Israel.

For the Palestinian Arabs, this event in their history – the loss of Palestine – came to be known as the “nakbah,” or disaster. For the great power interests in the region, the departure of the British opened up a fertile field for the Soviet Union in its aggressive objective of pushing its influence into third-world areas, including the Middle East. By the 1950s, Moscow had created friendships with many Arab states, while the U.S. had slowly moved in its relationship with Israel from distant friend, to occasional partner, to ally, and ultimately saw Israel as a strategic asset.While the U.S. sought to curb Soviet penetration of the Middle East, as demonstrated in the 1947 Truman Doctrine, the tense eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation between Moscow and Washington evolved over the Berlin blockade in June 1948. Despite the mutual contentiousness over Berlin, both countries, for differing reasons, recognized Israel within two days of its establishment on May 15, 1948.

By the end of the 1947-1949 war, rank and file Palestinian Arabs had their prerogatives and political ‘voices’ usurped by self-interested and self-absorbed Arab leaders, facing the challenges of “divided leadership, exceedingly limited finances, no centrally organized military forces, and no reliable allies.”[1] It took another four decades after the 1947-1949 war for Palestinians to assert their own independent political voice, no longer stifled by political leaders in Damascus, Cairo, Amman, the Arab League, and elsewhere. This finally happened in December 1988. For Arab states, the armistice agreements did not end physical or political hostilities; they were merely a temporary political interlude in the continuing effort to isolate, destroy, and delegitimize Israel internationally. For Palestinians and the entire Arab world, their defeat by the Zionists was viewed as only a failed ‘battle’ in the longer war to bury Zionism and remove Israel from the Middle Eastern political landscape. Arab states continued on that course until after the June 1967 war, when some Arab states and leaders began to question whether support for the Palestinian cause and Israel’s destruction was worth the sacrifice of manpower, money, and delay in national economic development. In the early 1970s, Egypt became the first Arab state to make and implement the calculation that ending the state of war with Israel was its primary national interest – not abandoning the Palestine cause, but placing its own sovereign interests ahead of Israel’s destruction or the liberation of Palestine.

-Ken Stein, July 2010

Preamble

The Parties to the present Agreement, responding to the Security Council Resolution of 16 November 1948, calling upon them as a further provisional measure under Article 40 of the Charter of the United Nations and in order to facilitate the transition from the present truce to permanent peace in Palestine, to negotiate an Armistice; having decided to enter into negotiations under United Nations Chairmanship concerning the implementation of the Security Council resolutions of 4 and 16 November 1948; and having appointed representatives empowered to negotiate and conclude an Armistice Agreement;

The undersigned representatives, in the full authority entrusted to them by their respective Governments, have agreed upon the following provisions:

Article I

With a view to promoting the return of permanent peace in Palestine and in recognition of the importance in this regard of mutual assurances concerning the future military operations of the parties, the following principles, which shall be fully observed by both Parties during the Armistice, are hereby affirmed:

- The injunction of the Security Council against resort to military force in the settlement of the Palestine question shall henceforth be scrupulously respected by both Parties.

- No aggressive action by the armed forces — land, sea, or air — of either Party shall be undertaken, planned, or threatened against the people or the armed forces of the other; it being understood that the use of the term “planned” in this context has no bearing on normal staff planning as generally practiced in military organizations.

- The right of each Party to its security and freedom from fear of attack by the armed forces of the other shall be fully respected.

- The establishment of an armistice between the armed forces of the two Parties is accepted as an indispensable step toward the liquidation of armed conflict and the restoration of peace in Palestine.

Article II

- In pursuance of the foregoing principles and of the resolutions of the Security Council of 4 and 16 November 1948, a general armistice between the armed forces of the two Parties — land, sea, and air — is hereby established.

- No element of the land, sea, or air military or para-military forces of either Party, including non-regular forces, shall commit any warlike or hostile act against the military or para-military forces of the other Party, or against civilians in territory under the control of that Party; or shall advance beyond or pass over for any purpose whatsoever the Armistice Demarcation Line set forth in Article VI of this Agreement except as provided in Article III of this Agreement; and elsewhere shall not violate the international frontier, or enter into or pass through the air space of the other Party or through the waters within three miles of the coastline of the other Party.

Article IV

With specific reference to the implementation of resolutions of the Security Council of 4 and 16 November 1948, the following principles and purposes are affirmed:

- The principle that no military or political advantage should be gained under the truce ordered by the Security Council is recognized.

- It is also recognized that the basic purposes and spirit of the Armistice would not be served by the restoration of previously held military positions, changes from those now held other than as specifically provided for in this Agreement, or by the advance of the military forces of either side beyond positions held at the time this Armistice Agreement is signed.

- It is further recognized that rights, claims, or interests of a non-military character in the area of Palestine covered by this Agreement may be asserted by either Party, and that these, by mutual agreement being excluded from the Armistice negotiations, shall be, at the discretion of the Parties, the subject of later settlement. It is emphasized that it is not the purpose of this Agreement to establish, to recognize, to strengthen, or to weaken or nullify, in any way, any territorial, custodial, or other rights, claims, or interests which may be asserted by either Party in the area of Palestine or any part or locality thereof covered by this Agreement, whether such asserted rights, claims, or interests derive from Security Council resolutions, including the resolution of 4 November 1948 and the Memorandum of 13 November 1948 for its implementation, or from any other source. The provisions of this Agreement are dictated exclusively by military considerations and are valid only for the period of the Armistice.

Article X

- The execution of the provisions of this Agreement shall be supervised by a Mixed Armistice Commission composed of seven members, of whom each Party to this Agreement shall designate three, and whose Chairman shall be the United Nations Chief of Staff of the Truce Supervision Organization or a senior officer from the Observer personnel of that Organization designated by him following consultation with both Parties to this agreement.

- The Mixed Armistice Commission shall maintain its headquarters at El Auja, and shall hold its meetings at such places and at such times as it may deem necessary for the effective conduct of its work.

- The Mixed Armistice Commission shall be convened in its first meeting by the United Nations Chief of Staff of the Truce Supervision Organization not later than one week following the signing of this Agreement.

- Decisions of the Mixed Armistice Commission, to the extent possible, shall be based on the principle of unanimity. In the absence of unanimity, decisions shall be taken by a majority vote of the members of the Commission present and voting. On questions of principle, appeal shall lie to a Special Committee, composed of the United Nations Chief of Staff of the Truce Supervision Organization and one member each of the Egyptian and Israeli Delegations to the Armistice Conference at Rhodes or some other senior officer, whose decisions on all such questions shall be final. If no appeal against a decision of the Commission is filed within one week from the date of said decision, that decision shall be taken as final. Appeals to the Special Committee shall be presented to the United Nations Chief of Staff of the Truce Supervision Organization, who shall convene the Committee at the earliest possible date.

- The Mixed Armistice Commission shall formulate its own rules of procedure. Meetings shall be held only after due notice to the Members by the Chairman. The quorum for its meetings shall be a majority of its members.

- The Commission shall be empowered to employ Observers, who may be from among the military organizations of the Parties or from the military personnel of the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization, or from both, in such numbers as may be considered essential to the performance of its functions. In the event United Nations observers should be so employed, they shall remain under the command of the United Nations Chief of Staff of the Truce Supervision Organization. Assignments of a general or special nature given to United Nations Observers attached to the Mixed Armistice Commission shall be subject to approval by the United Nations Chief of Staff or his designated representative on the Commission, whichever is serving as Chairman.

- Claims or complaints presented by either Party relating to the application of this Agreement shall be referred immediately to the Mixed Armistice Commission through its Chairman. The Commission shall take such action on all such claims or complaints by means of its observation and investigation machinery as it may deem appropriate, with a view to equitable and mutually satisfactory settlement.

- Where interpretation of the meaning of a particular provision of this Agreement is at issue, the Commission’s interpretation shall prevail, subject to the right of appeal as provided in Paragraph 4. The Commission, in its discretion and as the need arises, may from time to time recommend to the Parties modifications in the provisions of this Agreement.

- The Mixed Armistice Commission shall submit to both Parties reports on its activities as frequently as it may consider necessary. A copy of each such report shall be presented to the Secretary-General of the United Nations for transmission to the appropriate organ or agency of the United Nations.

- Members of the Commission and its Observers shall be accorded such freedom of movement and access in the areas covered by this Agreement as the Commission may determine to be necessary, provided that when such decisions of the Commissions are reached by a majority vote United Nations Observers only shall be employed.

- The expenses of the Commission, other than those relating to United Nations Observers, shall be apportioned in equal shares between the two Parties to this Agreement.

Article XI

No provision of this Agreement shall in any way prejudice the rights, claims, and positions of either Party hereto in the ultimate peaceful settlement of the Palestine question.

Article XII

- The present Agreement is not subject to ratification and shall come into force immediately upon being signed.

- This Agreement, having been negotiated and concluded in pursuance of the resolution of the Security Council of 16 November 1948 calling for the establishment of an armistice in order to eliminate the threat to the peace in Palestine and to facilitate the transition from the present truce to permanent peace in Palestine, shall remain in force until a peaceful settlement between the Parties is achieved, except as provided in Paragraph 3 of this Article.

- The Parties to this Agreement may, by mutual consent, revise this Agreement or any of its provisions, or may suspend its application, other than Articles I and II, at any time. In the absence of mutual agreement and after this Agreement has been in effect for one year from the date of its signing, either of the Parties may call upon the Secretary-General of the United Nations to convoke a conference of representatives of the two Parties for the purpose of reviewing, revising, or suspending any of the provisions of this Agreement other than Articles I and II. Participation in such conference shall be obligatory upon the Parties.

- If the conference provided for in Paragraph 3 of this Article does not result in an agreed solution of a point in dispute, either Party may bring the matter before the Security Council of the United Nations for the relief sought on the grounds that this Agreement has been concluded in pursuance of Security Council action toward the end of achieving peace in Palestine.

- This Agreement supersedes the Egyptian-Israeli General Cease-Fire Agreement entered into by the Parties on 24 January 1949.

- This Agreement is signed in quintuplicate, of which one copy shall be retained by each Party, two copies communicated to the Secretary-General of the United Nations for transmission to the Security Council and to the United Nations Conciliation Commission on Palestine, and one copy to the Acting Mediator on Palestine.

In faith whereof the undersigned representatives of the Contracting Parties have signed hereafter, in the presence of the United Nations Acting Mediator on Palestine and the United Nations Chief of Staff of the Truce Supervision Organization.

[1] Rashid Khalidi, Palestinian Identity The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 190.