Coming up, fifty years after the June 1967 War. How many times have I taught the causes and effects, or written about the War? Hundreds of times in forty years.

For years I used the premise that once Egypt put massive amounts of troops in Sinai and blockaded the Straits of Tiran at the entry to the Gulf of Aqaba and to Israel’s southern port of Eilat, Israel saw both actions as provocations for war.

Israel mobilized its citizen army, particularly after Arab leadership promised to eliminate the Jewish state. Israel launched a pre-emptive attack on Egypt’s air fields on the morning of June 5, 1967.

Israel wiped out Egypt’s air force in four hours, and in three days sped across Sinai to the Suez Canal. Until Arab leaders were emotionally driven to join Nasser’s war of liberation led by Egypt, Israel did not want to go to war against either Jordan or Syria; Israel preferred not to fight either Jordan or Syria, nor any predetermined intention to take the West Bank, East Jerusalem, or the Golan Heights. All true.

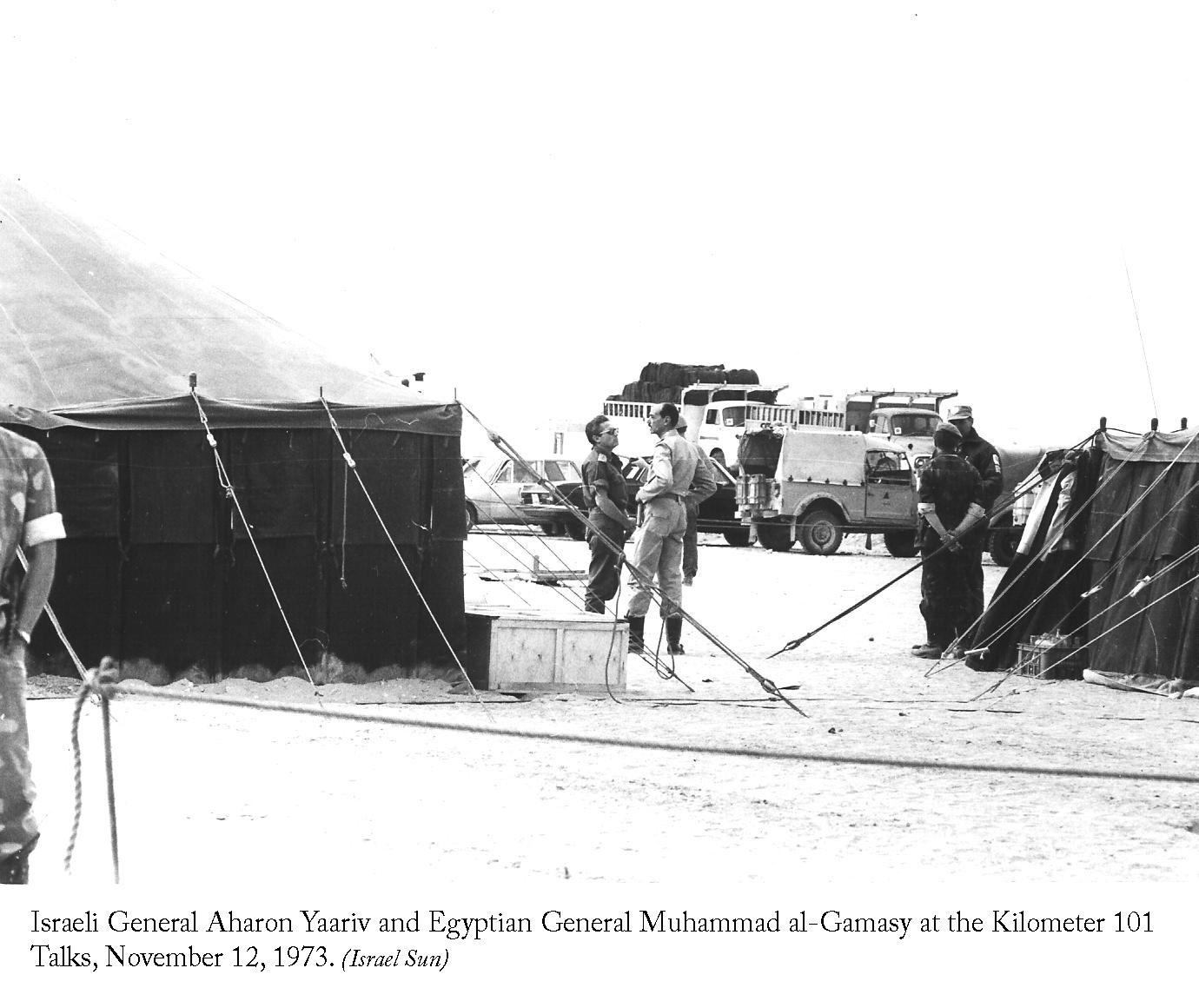

In preparing a CIE learning curriculum for adults and students to be ready for use in March, “The 1967 June War: How It Changed Jewish, Israeli and Middle Eastern History,” I looked at Arab sources not previously read about the war. Specifically I read Mohamad el-Gamasy’s memoir. El-Gamasy was part of the Egyptian military command at the time of the 1967 War, and later Egyptian Chief of Staff in the 1973 October War. He and an Israeli counterpart, Aharon Yariv negotiated the separation of their forces after the October 1973 War.

What was learned? El-Gamasy was brutal in criticizing the Egyptian military’s unpreparedness; he was scathing in blame heaped on Nasser for Egypt’s losses in the war, “Egypt was not at the time prepared for the war… our call up system was deficient, we had a shortage of officers and trained army, our air force lacked trained fighter pilots… fewer than the number of planes available, and there was a power struggle at the top between President Nasser and Abdul Hakim Amer, the Vice President.”

Amer and Nasser let their own personal squabbles and political aspirations take Egypt into a war, ignoring the army’s dramatic shortcomings. Egypt dragged the rest of the Middle East into a war for which it was not prepared, a war that led to Israel’s control over Sinai, the West Bank, Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and East Jerusalem; a war that led to Israel’s administration and occupation of the West Bank. What if Jordan’s King Hussein had stayed out of the June War instead of being sucked into Nasser’s political vortex?

El-Gamasy held the Egyptian political and military leadership accountable for the devastating Arab losses in the June War. Days before the war started, Nasser told a group of army officers, “We knew that closing the Gulf of Aqaba meant war with Israel.”

What is certain from El-Gamasy’s memoir, and from other sources, is that Nasser did not understand the massive consequences of a war with Israel. In terms of territory, when Nasser lost sovereign Egyptian Sinai, Sadat decided six years later that he needed it back by means of the October 1973 war and America led diplomacy. Indirectly Nasser’s 1967 War defeat spawned Sadat’s peace with Israel.

The June 1967 War certainly solidified Israel’s existence as a state, but just as at the end of the 1948 War, Arab states did not accept a Zionist/Jewish/Israeli state in their midst. Fifty years after the June War, Israel does indeed have peace treaties with Jordan and Egypt, and even quietly cordial relations with many Middle Easter Sunni Arab states. Egyptian President Sisi told a visiting American diplomat in August 2016, that the Egyptian-Israeli Treaty is a central feature of his country’s national security.

In June 1967, when Jordan lost the West Bank and East Jerusalem, Israel’s subsequent control over them has unfolded into highly controversial issues about how the areas should be managed and what their futures should be. The notion of settling in the West Bank was not on anyone’s agenda the day the June war started. The war spawned an entirely new enterprise called the “peace process,” and from it hundreds of written titles. The “peace process” led to a new set of political terms, “two-state solution,” “withdrawal from territories,” “settlements,” “unilateralism,” “land for peace,” “occupation,” “negotiations between the parties,” and others. The war’s aftermath unfolded bunches of negotiating ideas: accords declarations, initiatives, non-papers, parameters, plans, reports, resolutions, road-maps, working papers, and more. As far as the Palestinian-Israeli relationship is concerned, it remains open-ended, and a major unfinished element from the June War.