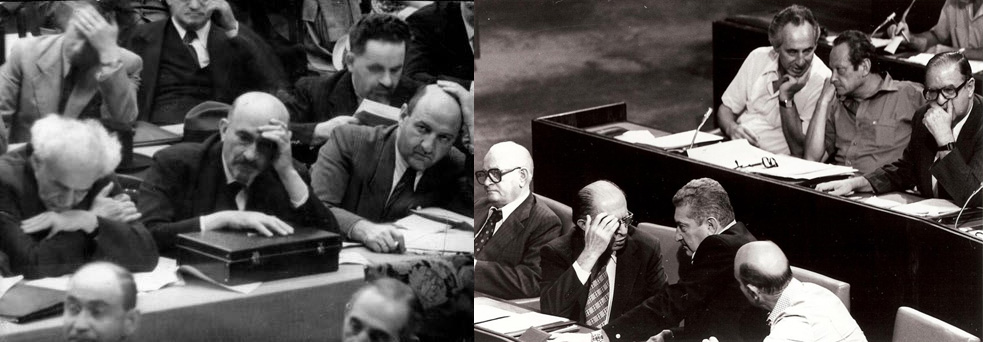

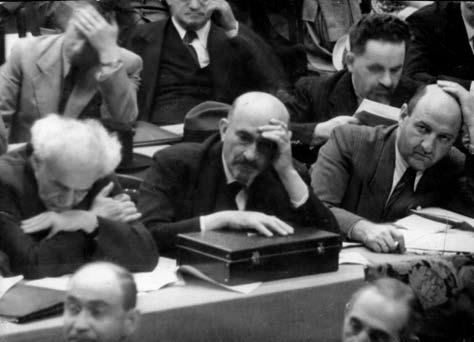

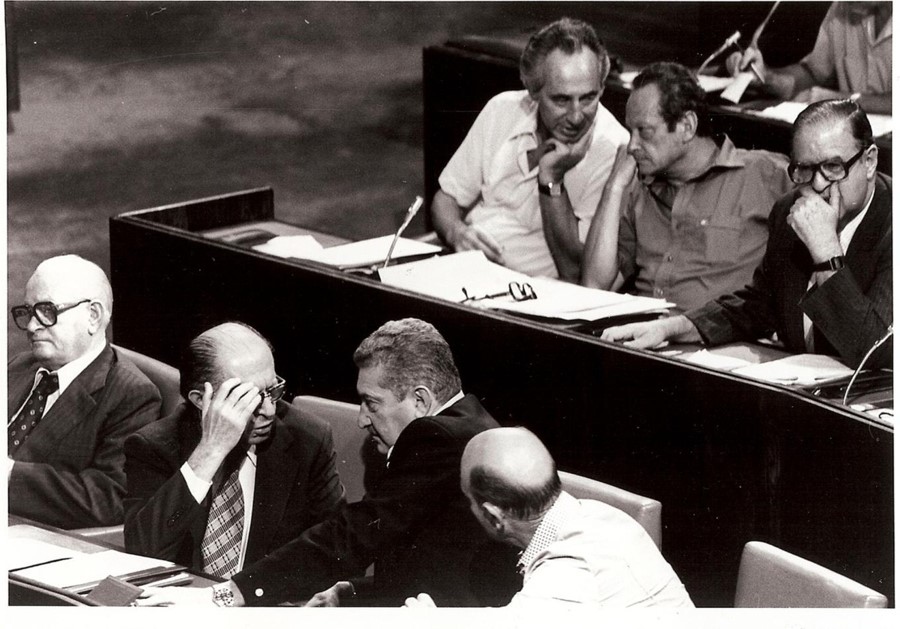

Right: Israeli Knesset, September 1978, Jerusalem Israeli leaders with Israeli Self-Determination. With Permission, Israeli Government Press Office

Professor Kenneth Stein, President Center for Israel Education

April 27, 2023

A connection exists from Jewish self-rule in the Diaspora to Zionist political autonomy during the Yishuv and to contemporary Israeli political culture. Likewise, the origins of Israeli democracy are found in the hundreds of years of Jewish Diasporas transitioning into the Zionist movement to Jewish state-building; from aliyot before the Palestine Mandate to the state and since 1948. Components of Israeli political culture and the elements of Israel’s democracy have evolved through Jewish history: adherence to core beliefs, a communal focus, pluralism, self-governance, self-defense, adapting to the majority non-Jewish world, institution building, and a stable of almost unending communal leaders who carried the baton forward.

Neither Israel’s political culture nor Israel’s democracy based on Jewish self-determination simply materialized on May 15, 1948.

Centuries of innovation and practice of autonomy emerged from centuries of collective Diaspora Jewish experiences. These experiences became part of the Jewish diasporic DNA, brought as luggage and baggage to the Zionist movement and to Palestine in the 19th and 20th centuries. In Palestine, without local Ottoman restraint, with countrywide socio-economic impoverishment and entrenched Arab political inefficacy, later stimulated by British encouragement, the exercise of Jewish/Zionist self-rule accelerated. State development through land purchase, immigration, and institution building defined and refined Jewish self-governance.

Very limited Jewish autonomy in parts of the Diaspora was a far distance from sovereignty. Jewish history and Jewish political culture in the Diaspora spawned self-governance. Variations of Jewish self-rule emerged as Jews lived as minorities, for example, in kehillot in Eastern Europe and in millets around the Middle East, established communal self-governance.

In a January 2021 presentation on Israel’s democratic origins, esteemed Hebrew University Professor Shlomo Avineri said, “The reason that Israeli democracy developed had to do with history. Jews did not have political power in the meaning of sovereignty and political power with armies and the military and total self-governance. But when you look at the way in which Jewish communities existed in Europe and in the Middle East, but mainly in Europe, you have to realize that until the Holocaust almost 85% of the Jewish population in the world were living in European countries. The Jewish communities in Europe and in the Middle East had centuries of experience of self-governance. The Jewish kehillah or the Jewish kahal, were really political entities in a very minor but meaningful way.”

In charting Jewish history through self-rule/autonomy, Avineri easily acknowledged that when Jews practiced self-governance, they had an abundance of shortcomings by modern standards. Women did not vote. Some regions and the Jewish enclaves within them were more oligarchic than others, as authority and leadership passed from one family member to another, or from one set of established leaders to another. When that occurred, some left a community and migrated to another. In the centuries before modern Zionism’s emergence, Jews practiced self-rule before they had a territory of their own. As a perennial minority wherever they lived, Jewish leaders, when they could define political compromise, engaged in marketing their cause, particularly in times of enormous insecurity and keen ruling opposition to maintaining Jewish rules, ethics and laws per biblical prescription and adaptation. Jews in Diaspora communities exercised authority and political/social autonomy without possessing sovereignty. Jews practiced self-governance before they had a territory; they exercised political and social autonomy without enjoying sovereignty. Before there was a state bureaucracy, they learned to be bureaucrats. Before there was a state government, Jews engaged in compromises, held elections, set agendas, disciplined their own with fines and more, grappled with crises, and managed obstacles where they could. Before they were citizens of a state, Jews created a budding civil society and became accustomed to judicial review.

In their pre-Palestine communal settings, Jews taxed themselves, educated their own, and endured both austerity and systematic persecutions. They shared a common ancient language and dealt with voices of dissent. Said the noted Jewish historian Jacob Katz, “Zionists were influenced by an extensive Jewish experience of self-government in the East European shtetl. This experience involved political institutions that were voluntary, inclusive, pluralistic, and contentious. It was also a closed system, facing a hostile external world and not equipped to deal with non Jews as a group. It was marked by the necessity of bargaining, lack of defined hierarchy, proliferation and influence of organized groups, and the reality of powersharing, rather than undiluted rule of the majority.” (Jacob Katz, Out of the Ghetto The Social Background of Jewish Emancipation, 1770-1870, 1973, pp. 210-216.)

Before Jews had a sovereign foreign ministry, they engaged in foreign affairs. Wherever Jews lived and it was needed, Jews lobbied their views to czars, dukes, kings, popes, and elites. Jews were granted charters to provide services and live sometimes in designated locations in the medieval and early modern periods; in giving allegiance to local rulers and a variety of concessions, these autocrats often preserved Jewish security for some designated period of time (Salo Baron referenced below).In 19th century Europe, heads of state, or the lawmakers decided the status of Jews, sometimes protected, sometimes they were allowed a modicum of equality, sometimes restricted in occupation and residency, sometimes systematically attacked either physically or verbally. It was the withering repetition of precarious existence that unleashed a Zionism that sought a political leader or state that would protect Jewish life and property. Jews sought to be citizens, not merely inhabitants.

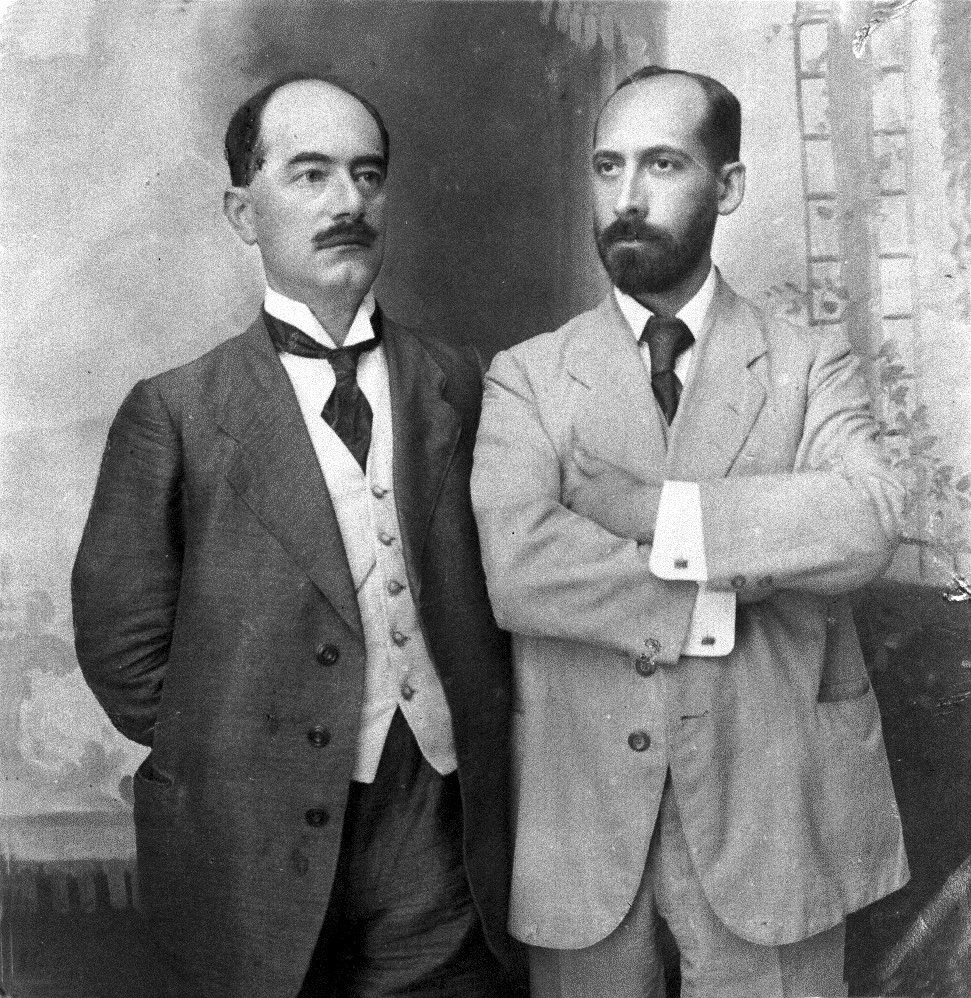

(With permission from the Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem)

Upon immigrating in several thousands to Palestine before World War I, Jewish preferences were to evolve and build their own institutions. The Zionists had created the World Zionist Organization and it met for the first time in Basle, Switzerland in 1897. From the WZO developed various committees, the Palestine Colonial Trust Bank and from it evolved the Anglo-Palestine Bank, the Jewish National Fund in 1901, and its Palestine office in Jaffa in 1907. For funding, the WZO sought contributions, but also applied a tax to its members. Between 1897 and the outbreak of WWI, the WZO met thirteen times expanding and inventing necessary institutions for the future state, as it did in 1913, when it resolved to build a Hebrew University of Jerusalem which opened in 1925.

On the Jewish secular side, Jewish self-government evolved when the British recognized in 1918, the “Zionist Commission” (ZC) led by Chaim Weizmann. It assisted Palestinian Jews in need and in crisis who had suffered during WWI. The ZC became a quasi-official political liaison with the occupying British military administration while other Zionists represented Palestine Jewish interests at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. When the British administration of Palestine officially began in 1920, the ZC became the Palestine Zionist Executive (PZE), led by a chair, Colonel Frank Kisch. Kisch met weekly with British High Commissioner Herbert Samuel’s administration about drafting laws and regulations pertinent to the growth of the Jewish National Home idea.

In 1920, the Jewish National Fund opened their Palestine office. Along with other financial and land settlement organizations, (Keren Hayesod, Palestine Land Development Company, Palestine Colonization Association), they were established to foster support and growth of the national home idea. The ZC and PZE evolved into the Jewish Agency (JA) that was officially recognized by the British in the Mandate to represent Jewish communal interests; for the duration of the Mandate the JA, and its predecessor the PZE, were the political liaisons to the British government in Palestine, to the League of Nations in Geneva, and to the international community in promoting the national home. Within the Jewish community, before and after 1920, Jewish political parties developed, representing all political shades from capitalism to Marxism. In building a workers society, a general federation of Labor (Histadrut) was formed which looked after workers’ needs from womb to tomb. Collectively but not always collaboratively, Zionists created the Vaad Leumi (VL) or Jewish National Council. In 1920, the self-established VL pulled together ideologically heterogeneous viewpoints. In 1937, the British credited the VL for counteracting divisive forces within the Jewish community and for forging a ‘national self-consciousness.’ It promoted universal suffrage. In 1928, the British gave legal recognition to it as it focused on attending to internal needs of the community, including health and social welfare needs, and education. From the first days in Palestine, the Jewish community took upon itself the education of its own and later under the Mandate, the British provided meager annual subventions to a much larger Arab population with greater degrees of illiteracy. Arab and Jewish education systems had no contact with one another; throughout the Mandate, “they widened the gulf” between the two communities said a 1945 British Report on the Jewish Education system in Palestine.

Newly arrived Jewish immigrants to Palestine from the 1870s forward chose mostly to live apart from Arab communities; they did not seek to be absorbed into existing Arab villages or live among the majority Arab population. Initially, they chose to live in the valley and coastal regions of Palestine, much of those areas sparsely populated. They did not for example seek to live in areas of Judea and Samaria, that had become the longest continuity of Arab village settlements. Jews applied their hard-learned lessons from European experiences of living apart; they built their own moshavim, kibbutzim, and villages. Most new Jewish immigrants had only limited engagements with local Arab populations. Ottoman Arab administrators in Palestine, like the successor British administration, showed little interest in encouraging physical or communal integration. For centuries in Mediterranean areas, Ottoman Arab authorities encouraged each religion to control its own civil matters – marriage, divorce, inheritance. With strong Jewish preferences and precedents in place from European experiences, and that of religious separation already in place, the British did not try social engineering to thwart either religious or secular separation.

Within the Jewish community, local Rabbinical Courts existed, and then nationally, competing rabbis styled themselves as lead rabbis up until February 1921, where the Jewish communities of Palestine elected a Palestine wide Rabbinical Council of two Chief Rabbis, one for the Sephardic and one for the Ashkenazic communities, respectively. The Arab communities in Palestine as early as 1919 established local Moslem-Christian associations, which in-turn created a Palestine-wide Arab Higher Committee to represent Arab political interests to the British. In 1921-1922, the British created the Supreme Moslem Council to oversee religious matters. With the February 1926 Religious Communities Ordinance in Palestine, the British reinforced communal separation. The Ordinance asserted that each religion could continue to make judicial rulings over its own communities and to request self-taxation for communal needs. Spatial distancing, self-regulating autonomy was reinforced with government sanctioned religious separation. British efforts to have Jews, Moslems and Christians engage in collaborative self-government failed, though Jews and Arabs populated the departments of the British administration in large numbers, as well as cooperated on local municipal governing institutions. Well before the British suggested in 1937 the physical partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, to relieve inter-communal violence, the British evolved institutional partition among the communities.

Where Herzl tried and failed to have the Ottoman Sultan grant Jews a charter to gain permission to build a Jewish entity, Weizmann and the London Zionist Executive succeeded in helping draft the Balfour Declaration. Jewish Agency representatives successfully advised Palestine Attorney General Norman Bentwich in the drafting of laws for implementation of the Mandate’s governance. Weizmann and others successfully lobbied against the implementation of the 1930 Passfield White Paper (Palestine policy statement) that would have put severe immigration and land acquisition restrictions on the Jewish National Home. Indeed, those choke holds on Jewish state growth were implemented in the 1939 White Paper, giving the Zionists a crucial decade of the 1930s to significantly expand their grip on Palestine geopolitically and demographically. In the same decade, the Jewish Agency “proved” that Arab land sales to Jews had not created Arab displacement. In the 1930s, JNF and Jewish Agency lawyers wrote and amended laws that allowed unimpeded acquisition of property from small and large Palestinian Arab landowners. Arab leaders meeting in Damascus in 1938 concluded that a Jewish state was in the making.

During the World War II period, the Jewish Agency spent great effort in seeking to smuggle Jews out hostile Europe. “Aliyah B” evolved for that purpose, (B stood for Bilti Legal – illegal immigration to Palestine). At the UN in 1945, Zionist diplomats worked against the proposition that the British might remain in Palestine, with renewed international sanction. In 1947, persistent Jewish Agency bureaucrats persuaded country delegates to vote in favor of the 1947 UN Partition Plan. The most impressive exercise of pre-state civil society engagement came in the first months of 1948. Without the rule of law forcing them, Jews in the Yishuv, voluntarily mobilized civil society, just as they supported from the 1930s forward organizing self-defense units in the decades before the state’s emergence.

With permission, Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel

[LR—David Ben-Gurion, Chaim Weizmann, Eliezer Kaplan]

With Permission, Israeli Government Press Office

[LR—Simcha Ehrlich, Menachem Begin, Ezer Weizman, Yigal Yadin]

[LR—Shimon Peres, Yigal Allon, Abba Eban]

On the way to becoming the state of Israel, the heterogeneity of the political culture was evident, friction-laden, and dynamic: Ashkenazim, Yemini, Poles, Germans, Sephardim, Mizrahim, Russians, Ethiopians, religious, non-religious, Jews and Arabs (Moslem and Christians), native born and recent immigrants. Israel in 2021 continues to evolve internally. Its relationships with its neighbors remains unfinished, just as the US was unfinished in 1848, 72 years after its birth. Israel is still evolving, with a steady and vociferous flow of voices, content and styles influencing its politics, culture, and a constantly “recooked” pluralistic nature. The ease and difficulties in absorbing immigrants are not confined to only people; it incessantly embraces culture in the forms of food, literature, music, politics, and so much more. Yet according to the 2020-2021 INSS National Security Index, there remains a deep national belief that being an Israeli provides enormous capacity of meeting any challenges ahead, with faith in their security establishment at 85%, a mere 25-30% of the population has confidence in their governments or government officials.

Israel has had 13 prime ministers; its November 2022 Knesset election is the 26th in 75 years. More than 800 individuals have served in the parliament. To say Israel is a vibrant democracy is an understatement: the civil society challenges to the proposed coalition’s suggestions for a judicial overhaul is the perfect case in point as highly diverse elements from within Israeli society have demonstrated week after week against giving one branch of government control over another.

Jews instinctively transported their centuries learned political culture from eastern European and Mediterranean and Asia minor origins. Jewish immigrants easily continued self-taught practices in the period before the state’s establishment. It was natural to see Israel’s first parliament evolve as a parliamentary democracy because Jews had accommodated minority viewpoints in the past, beginning at the first Zionist Congress in 1897. It was relatively easy to establish sovereign ministries from the departments that served Jewish needs during the Mandate. The commitment to sustain a national home evolved easily into commitments to defend the state. Despite vast differences in defining Zionism or the everyday role that religion was to play in state affairs, a deeply held singular belief existed, premised by the uncompromising ideal that Jews needed to be a free people in their land.

For further reading on the evolution and refinement of Jewish political culture and its democracy refer to Salo Baron, The Jewish Community: Its History and Structure to the American Revolution (1942). David Horowitz, State in the Making (1953); Leonard Stein, The Balfour Declaration, (1961); Alan Zuckerman and Calvin Goldscheider in The Transformation of the Jews, University of Chicago, 1984, pp. 3-75; Alan Dowty in “Jewish Political Traditions and Contemporary Israeli Politics,”Jewish Political Studies Review, 1990; Daniel Elazar, “Communal Democracy and Liberal Democracy in the Jewish Political Tradition,” 1993; Daniel Elazar, “The Jews’ Rediscovery of the Political and its Implications,” 1996; Jacob Katz, Out of the Ghetto – The Social Background of Jewish Emancipation, 1770-1870, (1973), Jacob Katz, Jewish Emancipation and Self-Emancipation, (1986) and Mosha Naor, “Israel’s 1948 War of Independence as a Total War,” Journal of Contemporary History (2008). For sources see Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State, (1896), Max Nordau, Address at the First Zionist Congress, (1897), Israel’s Declaration of Independence (1948), and Israel’s Basic Laws, (1958 – 2018). For an excellent analysis of Israel’s Declaration of Independence, please see Neil Rogachevsky, “Against Court and Constitution: A Never Before Translated Speech by David Ben Gurion,” Mosaic Magazine, March 10, 2021.

Finally, for a discussion of the elements in the domestic controversy of 2023, see a Review of the Four Elements of the Planned Judicial Overhaul.

Ken Stein

April 27, 2023