Ken Stein, Center for Israel Education, July 13, 2020

Introduction

Using original sources and employing perspective are keys to substantive Israel education. Failure to use either, handicaps and prejudices learning about Israel. When documents and texts or a broad overview of the literature in a field are not employed, there is a strong possibility that the educator either has a personal political agenda or, is covering up for their own lack of knowledge of what they are teaching. This premise is true for teaching any country’s history and through the lens of any discipline. I reside in the discipline of history.

It is fully understood that teachers of modern Israel—depending on age of students and educational settings—have limited times to teach about Israel. I adhere to three guideposts in teaching and therefore in Israel education. First, I start with the origins of Judaism covering Jewish history and experience through time. Why? The choice of where Israel’s story starts has a core impact on what one omits, what is conveyed, and what is condensed. It provides perspective. Second, in terms of successful pedagogy, I have found that blending sources with context of what came before and after is critical for understanding complexity. Third, I emphasize with examples that in every period of Jewish history, including today, Jews repeatedly reconfigured or realigned their perennial minority status to the geo-political realities of the non-Jewish world about them.

Where a teacher or author chooses to begin Israel’s story is a transparent foreshadowing of what students will learn. For more than forty years, I have read and witnessed Israel’s story told or taught using a variety of starting points: from the Bible, before 1840, 1897, 1903, 1917, 1945, 1948, 1967, 1979, and 1991 and more. Tell the story from before 1840 and the origins and development of Judaism are told along with peoplehood, expulsion, survival, Haskalah and early rumblings of Zionism. Teach it from 1945 forward and chances are that the devastation of the Holocaust will be the platform for understanding Israel and its Arab neighbors. Begin teaching modern Israeli history with the aftermath of the June 1967 war, and subsequent learning becomes pros and cons about what needs to be done with the territories, the “occupation,” or in the “peace process,” terms all born in June 1967. The learning that funnels Israel’s relationship with the Palestinians, as if there was no pre-history; it then omits lessons learned from the 1956 and 1948 wars, the 1947 partition, Zionist nation-building, Arab decision-making to boycott any compromise with the Zionists, or Jewish history from biblical times. When the history of Israel is taught only in the context of the conflict, there are usually not so hidden explanations: both the teacher detests history and perspective in general or worse possesses an invidious acceptance that either Jews as a people or Jewish history is irrelevant.

Devotion to sources: an intersection of personal and professional journeys

Like the history of all countries, Israel is unfinished. It may be 72 plus years old, but its history predated the events of May 1948, perhaps by as much as 3000 years. American history did not start in 1776, but rather before 1620 and Plymouth Rock. German and Italian history certainly began before the 1870s. Modern Israel did not evolve simply because of anti-Semitism, an outbreak of pogroms, and what befell European Jewry between 1933 and 1945. Israel emerged because the organizers of the idea for a state had inherited a central core from diaspora existence, that Jews centered their lives on belief, Torah, Eretz Yisrael, ethics, and community. They continuously found ways to maintain traditions while reconciling their Judaism to the changing world about them. Adaptation within limitations is as much a part of Jewish and later Israeli history as is the “Exodus”, expulsions, and egregious anti-Semitism.

Before college, I thought that Israel came into being because the western world felt remorseful about the destruction of one-third of world Jewry. Early in college, I remember referring to modern Israel’s creation as payback for Jewish suffering in the Holocaust. I learned later that many smart people deeply believed that without the period of 1939-1945, Israel would not have materialized. At age 18 or 19, I had no idea that Israel evolved through persistence, strategic thinking, or lobbying for a cause. What changed my view? I had superb teachers at the University of Michigan and at the Hebrew University in the late 1960s and early 1970s. They taught me to question accepted premises through reading original sources.

For a period of nine months in 1972 and 1973, while doing dissertation research, I sat daily in a warehouse in Kiryat Eshkol in Jerusalem. Pouring over some 2500 boxes, with an average of 11 files per box with material from the Land Registry offices of the British administration in Palestine, I learned the reasons and processes through which Jewish immigrants acquired land from middle class as well as impoverished yet willing Arab sellers. I found corroboration about those sales in hundreds of articles in Palestine’s Arabic newspapers from as early as 1931! These findings were reinforced in detail by Jewish histories such as Sefer Toldot Hahaganah, Sepher HaPalmach, Yomani (Yosef Weitz), and documents in hundreds of files from the Jewish Agency’s S25 Political Department files, housed at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem. Transcripts of Jewish National Fund meetings from 1924-1948, also housed in the Central Zionist Archives confirmed the intricacies of land transfers and the politics surrounding them. British mandate administration, Colonial Office records, diaries and memoirs provided first-hand accounts of transfers stating unequivocally Arab Palestinian complicity in assisting the Zionists create the state. In later years, the writings of Musa Alami, Issa Khalaf, Rashid Khalidi, and others confirmed a broader picture of the disintegrating nature of the Palestinian Arab community in the late 1930s and 1940s. Indelibly and undeniably, I learned how the geographic nucleus for a Jewish state evolved dunam by dunam, in parallel to Hitler’s rise to power in Germany. I wrote my daily archival collections on 3×5 cards, and then converted those thousands of cards into chapters of a book. These notes became chapters in The Land Question in Palestine, 1917-1939 (1984); I pieced together other socio-economic issues present in the British Mandate from Hebrew, English, and Arabic sources. They detailed Zionist finances, Jewish institutional development, fragmentation of the Arab community, the Arab population’s chronic impoverishment, the disastrous impact on the Palestinian Arab economy of the 1936-1939 unrest in Palestine, and concluded as did Arab notables who met in Damascus in 1938, that a Jewish state was lurking around the corner before Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939. I dared to conclude in a speculative article that there was a demographic and geographic nucleus for a Jewish state by 1939.

Choice—the link to self-determination

Still, major holes existed in my perspective of Israel in the context of Jewish history. I possessed only a limited understanding of how Jews lived in biblical, ancient, and early modern times and interacted with surrounding rulers. For about two months in fall 1972, I took a vacation from archival research and the #9 bus, and sat at the Hebrew University library in Givat Ram. I read how Jews in earlier centuries in the Middle East and Europe organized themselves and survived. Existing as demographic minorities wherever they lived, Jewish populations took challenges and turned them into opportunities. Alternatively, depending on stability or precariousness at any one moment, Jews repeatedly asked the gnawing question: do we stay or do we go? My grandfathers answered the question in the affirmative in the late 1920s and 1930s. They sent their offspring to America from Germany.

To survive in the diaspora, whether in the Middle East or Europe, Jews learned to negotiate with the local religious or political autocrat. Jews did not wallow too often or too long in being victimized for their beliefs. They learned to improvise ways to manage unfriendly bureaucracies and lethal autocrats. Jews developed lobbying skills centuries before they had a foreign ministry. How many times did Jews negotiate rights or seek a charter from a ruler? What was Chaim Weizmann doing with the British in the World War I period other than negotiating a charter or declaration for Britain to give permission to Jews to build a homeland under the protective umbrella of a great power? What did Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu try to do in March 2015 other than seek to persuade American politicians that an Iran deal was neither in Israeli or American interests? Skills learned in the diaspora carried over to state making and state keeping.

The key concept that evolved from my self-imposed reading course was the repetitive appearance of Jews retaining choice. Jews chose to believe in one G-d; they chose to organize themselves; they threw up their hands in the middle of the 1800s and some of them said—as in the movie Network—“I am not going to take it anymore.” Zionism was a movement and a move. It took Jews from being a weak object in someone else’s sentence to becoming the central subjects of their own sentences. Having your own say where liberty and freedom could be practiced, transformed Jewish life from overwhelming powerless to accessing power.

For teaching purposes, I place Israel’s story into four phases: evolution and sustaining peoplehood, state seeking, state making, and eventually state keeping. My life-long study of how Jews acquired a geographic nucleus for a state was part of the state making. My task as an Israel educator—using the historical continuum to track learning —is to explain what happened in these four respective phases. Then to connect seamlessly the phases together. The common conceptual thread between each of the last three phases is choice—“lehiyot am hofshi bearztenu”—to be a free people in our land. The concept of choice resonates in seeking, making, and keeping a state. Zionist and Israeli decision makers exercised choices. There are many, here are a few: organizing a movement with action orientation, linking people to the land, building settlements, resurrecting Hebrew as a spoken language, initiating “Aliyah Bet, lobbying for partition, choosing not to have a constitution, acquiring nuclear power, absorbing 850,000 Jews from Arab lands, striking pre-emptively in June 1967, building settlements, rescuing Entebbe hostages, making peace with Sadat, destroying the Iraqi nuclear reactor in 1981 and refusing to respond to Iraq’s scud attacks in 1991, and withdrawing unilaterally from Gaza and northern Samaria in August 2005. There are hundreds of more examples of Jewish self-determination, including too many to count on the domestic scene. In hindsight, some of the choices made have been controversial ones, but they were Jewish choices. Choices made by Zionists or Israeli leaders have been strenuously opposed by Jews in the diaspora, and vice versa. Hundreds if not thousands of more choices are still to come because Israel remains unfinished.

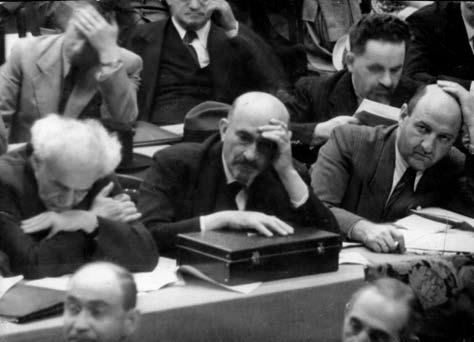

Jewish leaders without self-determination

March 1939 Zionist Congress, eve of WWII

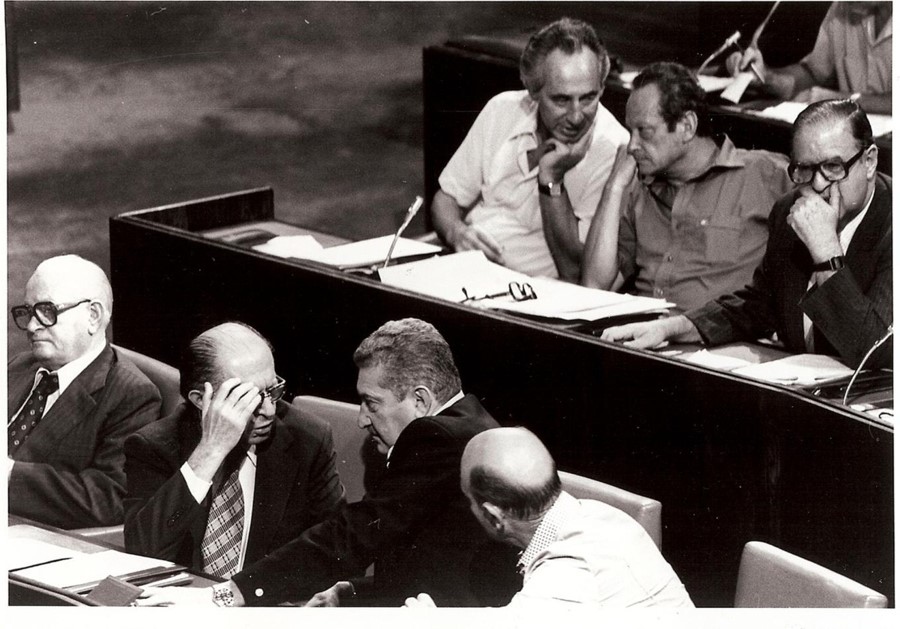

Israeli leaders with self-determination

September 1978 Knesset Debate on Camp David

Conclusions

All students and teachers approach a topic of learning with different levels of depth, detail, and objectivity. Layering learning insures comprehension. Repetition of what we already know when met with new discovery refines understanding, except if we have a closed mind and are emphatically resistant to allow new ideas to change long-term beliefs. In two books written sixty years apart, When Prophecy Fails, 1957 (Festinger, Riecken and Schachter) and The Influential Mind, 2017 (Sharot, an Israeli neuroscientist), the conclusions were the same: facts and evidence do not matter if you believe something deeply enough.

Show a person fact, they may question your sources. Present undeniable and unequivocal evidence that goes against a deeply held belief, what happens? The smarter the person is, the greater the preparedness is to rationalize away disagreeable information. In other words, the person will question your facts and sources, emerging not only unshaken, but also generally remain more convinced of the truth of their earlier beliefs than before new data points were provided.

In the teaching of Israel, it happens all too frequently because educators impose their political preferences, what they omit or include in assigned readings. One well-known Israel educator at the Jewish Agency conference on Israel education held in October 2018, in Jerusalem said, “Israel is an embarrassment, I can’t teach it.” Several years ago at a conference in Chicago, another noted Israel educator when presented with the documentary evidence that Palestinian Arabs in the 1930s acknowledged that they were colluding with Zionists, he could not absorb that into Israel state building. His view, I learned later was that only the Zionist were responsible for Palestinian dispossession. “Are you sure of the sources,” he asked, even with the sources in front of him. Gordon Pennycook and David Rand suggested in the New York Times in January 2019, that people fall for fake news because they are blinded by their political passions or are intellectually lazy. Both authors reinforced the conclusions of the two books noted above. Perverting a story to fit our personal preferences does not have a place in education. Personal political feelings or agendas have no place in teaching, and that includes teaching about Israel. Refusal to teach about Israel is denial of its connection to Jewish history. Educators have a responsibility to teach without fear or favor, to teach Israel’s story diligently to our children. What works effectively in teaching Israel and the Middle East for old and young alike? Constantly absorbing new data and information from textual sources. Blending them with context and perspective has proven enormously compelling.

A shortened version of this article was presented as a paper at a forum on new horizons in Israel Education sponsored by MAKOM and the Jewish Agency in October 2018. The forum was held in honor of Alan Hoffman. The full article, “Proven Success in Israel Education – Context, Sources and Perspective,” appears in Jonny Ariel and Alex Pomsen (eds.) Israel Education: The Next Edge, Makom, The Jewish Agency, Jerusalem 2020.

- “Analyzing Primary Sources” a guide to teaching with them, with case learning activities, Center for Israel Education, https://israeled.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Analyzing-Primary-Sources-Documents.pdf

- Kenneth W. Stein, “What if the Palestinian Arab Elite Had Chosen Compromise Rather than Boycott in Confronting Zionism?” in Gavriel D. Rosenfeld (ed.) What ifs of Jewish History, Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp. 215-237. http://ismi.emory.edu/home/documents/What%20if%20Arrabs%20not%20Boycotted%20in%20Mandate.KWS.pdf

- Amira Hass, Haaretz, April 18, 2001, Usmah al-Baz, Special Adviser to the President of Egypt, Cairo, Middle East News Agency, May 21, 2002; Jerome Shahin, Lebanese daily, al-Mustaqbal, December 22, 2005.

- 1945-1949, A Collection of Reasoned Views for the dysfunctional state of the Palestinian Arab’s political state of affairs, Center for Israel Education, https://israeled.org/themes/arabs-palestineisrael/1945-1949-reasoned-views-for-palestinian-arabs-dysfunctional-condition/

- “Zionists and Arabs – Sources Unfold the Jewish State State-Seeking, State-Making, State-Keeping Socio-Economic and Geo-Political Histories,” https://israeled.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/STATE-Making-CORE-state-making-pdf-6.25.-TEXT.pdf

- Kenneth W. Stein, “Palestine’s Rural Economy, 1917-1939,” Studies in Zionism, Vol. 8, no.1 (1987), pp. 25-49. http://ismi.emory.edu/home/documents/stein-publications/siz87.pdf, Hebrew version, Cathedra, Vol. 41, October 1986, pp. 133-154.

- Gershon Agronsky, “Palestine Arab Economy Undermined by Disturbances,” Political Department, Center Zionist Archives, January 20, 1939, S25/10.091, Center for Israel Education, Center for Israel Education, https://israeled.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/1939.20.1-Jan-Agronsky-CZA.pdf

- Arab Leaders Meeting in Damascus, September 30, 1938, Center for Israel Education, https://israeled.org/resources/documents/arab-leaders-meeting-damascus/

- Kenneth W. Stein “A Zionist State in 1939,” Chai (Atlanta), Winter 2002, http://ismi.emory.edu/home/documents/stein-publications/c122002.pdf

- With permission of the Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel and the Israel Press Office, Jerusalem, Israel.