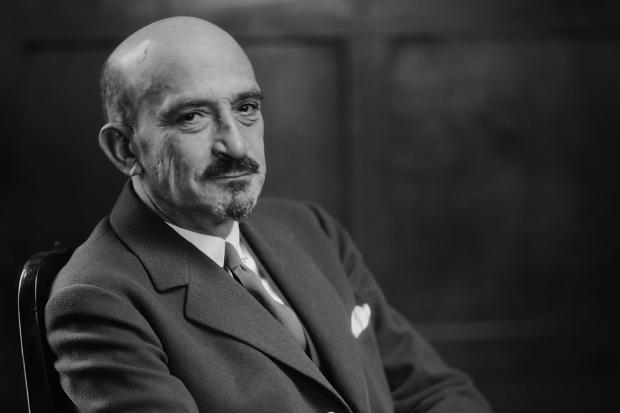

The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann, Volume II, Series B (December 1931 – April 1952), Volume II, Series B, Editor: Barnet Litvinoff.

Weizmann traveled to Palestine in November 1937 and made two widely publicized speeches in Hebrew, based on these notes. He addressed Va’ad Leumi in Jerusalem on January 23, 1938, and a mass meeting in Tel Aviv on February 3, 1938. While in the country he was heavily guarded.

1. Looking back on past few months stay in Palestine, am going away greatly heartened by what I have seen. Don’t want to minimize in the least what the Yishuv is going through at present: shall certainly not minimize it in London. At the same time have been enormously impressed by the strength and resource the Yishuv has shown both in economic and security spheres under most unprecedented difficulties and in face of constant provocation. Refer briefly to last week’s visit tot h North and to Emek Hepher. What I have seen there is an indestructible force, a force as real as the rocks of Palestine. I have seen a people which has become again rooted in its land. The Jewish boys and girls in Emek Hepher are parts of the landscape of Palestine. They look as though they and their parents and their grandparents had always been there. There is the strength of the soil in Jewish Palestine. The Jews have transformed the physiognomy of this country. They have brought to life again the old strength that was slumbering in this soil for thousands f years. That is the message I am taking with me to the world at large. A new generation has grown up, which I am deeply convinced is capable of taking upon it the new political responsibilities which it is intended now to impose upon it. In London they have not yet sufficiently understood what is happening in this country. They have to be told that this force has come to stay and to grow and that it is impossible to make any arrangement whatsoever in regard to this part of the world without taking this force into account.

2. Let me again briefly analyze the situation. You all know the Report of the Royal Commission, how it viewed the situation, and what two forms of remedy it prescribed. Their essential analysis was to the effect that Arab and Jewish aspirations could not be satisfied within the framework of the Mandate and that the latter was therefore inherently unworkable. Let me say at the outset that all of us, whatever our attitude towards the concrete recommendations of the Royal Commission be, regard this analysis as definitely incorrect. It runs counter to the view which has been officially upheld by every British Government and by the League of Nations ever since the Mandate was created. The complexity of the task which was inherent in the Mandate was always realized, but government after government, and session after session of the Mandates Commission, declared that there was no fundamental incompatibility between the several obligations imposed on the mandatory Power. We maintain that the unprecedented prosperity which all sections of the Palestine community attained under the regime of the Mandate, the unheard of improvement in the conditions of life, of health, of education of all sections of the population, which is evidenced from such facts as increase of the Arab population by more than 50 per cent, and the phenomenal reduction of the infantile mortality rate, we maintain that these facts have shown that the Mandate offered wide opportunities of beneficial development to both e sections of the population. The Royal Commission saw Palestine in the aftermath of a period of unprecedented disorders which, as suggested in the observation s of the Permanent Mandates Commission, and may even be implicit in the Royal Commission Report, might well have been stopped at an earlier stage by a more definite and resolute policy of the Palestine Government.

If the Royal Commission had seen the country in a more tranquil state, such as prevailed during the preceding years, they would assuredly have found many elements of cooperation between Jews and Arabs which encouraged the hope of a future collaboration of the two nations in an undivided Palestine. It was certainly the conviction of authoritative Jewish opinion that as the country developed under the Mandatory regime and all sections of the population shared in its progress, a modus vivendi would be evolved between Jews and Arabs free from the virus of fear and of domination. Nor were these aspirations without response from the Arab side. In various fields of economic and social activity contacts were being established between Jews and Arabs which, though still tenuous, held out the respect of eventual collaboration in wider spheres.

3. For all these reasons, we Jews cannot accept the thesis that the Mandate has failed. The Mandate has never had a really fair chance from those who were entrusted with its administration. Subjective and objective factors were responsible for this. There was the romantic conservatism of those who wanted, at all costs, to preserve the East as it is; there was the aversion to the ‘foreign’ psychology of the Jewish immigrants; there was the incapacity of the average colonial official to deal with such an essentially un-colonial population as Palestine Jewery; there was also, I am afraid, the genuine anti-Semitism. But over and above everything, there was the failure of the official mind to grapple, in the daily routine of administration, with the problem of the creation of a new society within the existing order of things. The task imposed on the Mandatory Power was not incapable of execution; the Mandate was not unworkable, but it required a high degree of administrative statesmanship to translate its abstract provisions into concrete deeds. This is where the Administration of Palestine has failed. It failed completely to visualize the latent forces of Jewish development which, in these two decades, have so fundamentally transformed the economic and social structure of this country. Their unimaginative outlook inevitably led them to keep their minds fixed entirely on the Arabs and to conciliate those whom they regarded as dominating Arab opinion. Such a line of thought was bound to militate against the pursuit of a vigorous constructive policy for implementing the National Home clauses of the Mandate. It produced an opportunist policy of compromise and vacillation, which of necessity prevented the Arabs from believing that the Administration was genuinely concerned to give effect to the National Home conception. It strengthened the influence of the Arab irreconcilables and it weakened that large body of Arab moderate opinion which might well have been led to adopt a positive attitude towards the Mandate if the Administration had shown that it was resolved to carry it into real effect. It was not, as the report of the Royal Commission suggests, bombs and machine guns that were needed to give effect to the policy embodied in the Mandate. What was needed was a genuine belief on the part of the Administration of Palestine that the task entrusted to it was both equitable and practicable. Had there been this conviction from the very beginning, and had firm and consistent effect been given to it in action and omission, no repression would assuredly have been considered necessary to carry the Mandate into effect.

4. If for all these reasons Jews cannot accept the thesis that the Palestine Mandate has been tried and found unworkable, we realize, on the other , that we cannot ignore the fact that this view has been adopted by the Royal Commission and has been officially endorsed by the British Government.

This authoritative pronouncement of the Royal Commission and the British Government has created a new situation which has to be faced, even if the analysis on which it was based is wrong. The Permanent Mandates Commission, which was as skeptical of this analysis as we are, made the following observations on this subject: ‘The application of the present Mandate became almost impossible on the day when it was publicly declared to be so by a British Royal Commission speaking with the double authority conferred upon it by its impartiality and its unanimity, and by the government of the Mandatory Power itself.’ But if the situation thus created has to be faced, it becomes all the more urgent that, in discussing any schemes for political reconstruction, the underlying purpose of the Mandate should be kept clearly in view, and that the errors committed in the administration of the Mandate should not be repeated in determining the character of any new regime that may be established in its place.

5. Mandates have been liquidated before now, but in all those previous cases the essential question asked by the League of Nations was whether the Mandated territory had reached the degree of maturity which would justify its emancipation from the Mandatory regime. In the case of Palestine, the Mandatory Power, to use the words of the P.M.C., pleads ‘not so much the maturity of the ward, as the difficulties of the tutelage.’ There is another difference. In the other cases, the ward was already there, it was merely a question of whether he was mature enough for self-government. In the case of Palestine, to use the same simile, the ward has not even yet established it full identity. The Jewish nation whose indissoluble connection has not been internationally recognized, is at present represented in Palestine only by a small minority of its numbers. It is there only as it were potentially, and the essential object of the Mandate was to transform that potentiality into a reality. Whatever new order may be set up in this country, we have a right to demand that it shall be so designed as to render possible the continuous consummation of that process of re-establishment. That means that the problem cannot be solved on static lines. If the proposed political reconstruction of Palestine is carried through with the view only to the population which now inhabits this country, this would mean to repeat the same error of policy as has vitiated the administration of the present Mandate. If it is really held that a Mandate is unable under present political conditions to facilitate the development of the Jewish National Home which it was established to promote, then it is all the more important that the regime shall be so constructed from the beginning as to enable a more effective realization of that object.

6. For, on one point, there is no disagreement between us and the Royal Commission. If it had doubts in regard to the workability of the Mandate, it has in no way disputed the urgency of the underlying purposes of the Mandate. On the contrary, the deep significance and urgent necessity of the National Home policy, both from the Jewish and the international point of view, and the force of the promise embodied in the Balfour Declaration, have rarely been expounded with such eloquence as in the opening sections of the Report. They have also testified to the reality of Jewish achievement in Palestine and to the substantial benefits it has conferred on the Arab population. On the basis of their own analysis of the situation we have a right to claim that the progress of our work shall not be hampered, but shall be effectively assisted and creatively promoted through whatever new regime arises from the present discussions.

7. And this brings me to the actual problem which we now have to face. Let there be no mistake about one thing: any form of partition involves a very real sacrifice to every Jew. To all of us – not merely to Ussishkin and his friends – the hills of Judea and Samaria are as precious as the coastal plain and the Valley of Jezreel. But if we are asked to make that sacrifice, it can be only if by doing so we can save the realization of our essential idea. We cannot accept a caricature of tour supreme national object. If we have to acquiesce in a reduction of the area of the Jewish National Home, the limited area which is left to us must be such as to enable us to do three things: (a) To maintain ourselves strategically; (b) to build up an economic life which can stand on its own feet; (c) to find scope here for a continuous Jewish immigration which will bring to Palestine such a proportion of the Jewish people as to make the new settlement an organic continuation of the historic entity of Israel.

8. The object of the National Home policy embodied in the Mandate was twofold: it was first to give to the dispersed and homeless Jewish people a national and a political status in Palestine – as distinct from the exclusively civic status which Jews, qua Jews, enjoy in other countries. In the second place it was to make an effective contribution towards the solution of the Jewish world problem, by enabling a representative portion of the Jewish people to settle in this country. The terms of the preamble and a detailed provision of the Mandate made it clear that its object was not to establish in Palestine an exotic little community of Jews living in an Arab ghetto. Its object was to recreate in Palestine the historic Jewish nation.

9. It was because we felt that the concrete scheme embodied in the Peel Report did not conform to these requirements that we rejected it is Zurich. But let us be fair to the Peel Commission. Let us acknowledge that in devising their scheme they realized that it would be absurd, that it would be unfair, that it would be a betrayal of the promise of the Balfour Declaration and of the Mandate if we were given only that which we already possess, if we were not given room for bringing over Jews and establishing here a comprehensive Jewish settlement of several millions. Their frontiers may have been badly designed; the conditions they attached to their scheme may have been ill-conceived, but eh underlying idea of their conception was sound. They wanted to give us, in addition to what we have an area which, on the basis of the facts which are known, would be capable of extensive development and of absorbing large numbers of Jews. They did not choose the easy road which is not advocated by so many of our good friends, who suggest that instead of the areas which we know as being capable of absorbing Jews, we should be given districts which at present re desert land and which even we, with all our energy, may no longer be able to save for cultivation.

10. I think that in a situation of this kind and knowing the desperate position of the mass of the Jewish people today, Jewish leaders should have been eager to improve the offer of the British Government to the best of their ability, but not to destroy it by very shortsighted tactics. Instead of realizing that this offer gave us a most unexpected chance not merely of saving the Jewish National Home but of developing it in accordance with our own conceptions, some of our people suddenly lost all sense of reality. Some shouted “No”, because they refused to give anything away of Palestine. Others rejected the idea because they would not concede to Jews the ability to run a state of their own which they readily attribute to every non-Jewish people however primitive. Then again there were those who stoutly maintained, after all that was happening in Germany, Poland and Rumania, that the Jewish Diaspora status must be maintained at all costs and that the establishment of a Jewish State would endanger the position of Jews in the lands of their dispersion, glorious as we all know it to be.

However wide their divergencies of outlook and motive, all these outright opponents of partition use in discussion the identical critical arguments – which in reality are arguments not against partition in the abstract, but against the concrete partition scheme suggested by the Royal Commission. The small size of the proposed Jewish State, its untenability on strategical and political grounds, the unsatisfactory financial arrangements to which It would be subjected in relation to its Arab neighbor, the difficulties associated with the proposed population transfer – these and kindred arguments occur equally in the pronouncement of all these groups. Every one of these arguments against the scheme of the Royal Commission contains much that is true, but the conclusion which realistic political leaders should have drawn from these concrete criticisms should have been to make a united effort to get the Royal Commission project so changed as to produce a viable Jewish political unit capable of progressive development. Had the British Government been shown that at least one side – the Jews – were prepared to make something of the partition idea they might very well have felt impelled to carry it through in a way which would give satisfaction at least to that side which accepted it.

11. As it is, the government is told that the Arabs do not want it and that the Jews – to judge from the utterances of Anglo-Jewish leaders, prominent American Zionists, the Anglo-Jewish Press and even some outstanding Palestinian Jews – also do not want it. So it is very easy for our common enemies to argue that the only thing to do is to scrap the whole issue and to ‘solve’ the problem by liquidating the Jewish National Home. These Jews have provided most welcome ammunition to our enemies here and abroad. We definitely know that the Arab politicians are building great hopes on the dissensions in the Jewish camp. They believe that if the present phase of negotiations can be dragged out and partition comes to grief as a result of Arab intransigence and Jewish internal dissentions, everybody will be so tired of the whole business as to swallow their ‘solution’ of an independent Arab State with a permanent Jewish minority, the latter to provide the financial wherewithal for the upkeep of Arab political glory as in the good old days. I do wish some of our people would realize what dangers are lurking in their path and ours in consequence of their short-sighted obstructionism.

12. A word about the new statement of the government. It is gratifying in so far as it indicates that the government has not listened to those who urged on it the surrender of the Jewish National Home to its enemies, who for two years have been fighting it with bombs, with intrigues, with calumny. On the other hand, it shows that we have to start again from the beginning an we have to make out our case on its merits.

We are prepared to do so and I think we shall succeed as we essentially succeeded last year. But we must have behind us a united people in order to carry this through. I want to get such terms as will enable us to safeguard what we have, and to provide scope for that which still has to be built.

13. The most urgent need at the present moment is that a speedy decision be taken regarding the political future of this country. If there is determination in high quarters all these preliminary enquiries can be carried through within a comparatively short period of time. That would prevent any terrorist outbreak, bring about a quick restoration of confidence and enable the economic development of the country, which has suffered terribly from this long delay and uncertainty, to be effectively resumed.

14. Above all we need a return to the normal in the matter of immigration. This new Jewish society which is growing up in this country, and which is already an ineradicable part of it, cannot live without immigration. It is its lifeblood. It is an intolerable state of things that an arbitrary emergency measure like the imposition of the political high level should be introduced expressly in an emergency of temporary duration, and that then this emergency state should be kept in being for an indefinite period. We shall oppose any continuation of this arbitrary restriction of Jewish immigration with utmost force. The discussions of this summer both in the P.M.C. and in the Council of the League have shown us that in this great issue international opinion is on our side.

15. I have three messages. One to the Jews. One to the Arabs. One to the British Government.

My first is to the Jews, here and everywhere. What I ask from them is that there should be a stoppage of the internal Jewish controversies on partition until a definite scheme has been worked out, and can be considered and decided upon. I ask that nothing shall be said by authoritative Jewish voices in public and in Press which may lead the outside world to believe that Jews would accept anything short of the effective realization of the National Home conception. I am asking for a Burgfrieden while the battle is raging outside. This is all I ask but I ask for it in full.

I do not envy the responsibility before ht forum of Jewish history of those who, at this critical hour, join hands with our worst enemies to destroy that which may be our last chance.

Secondly, to the Arabs I say: we repeat in this hour what we have always said. We have no ill-feeling in our hearts against you, in spite of all that we have gone through in these two years. We hoped and believed that under the Mandatory regime there was room for joint development for both of us. You have seen what progress you have made in these 20 years under that regime which was created for the purpose of facilitating the establishment of a Jewish National Home in this country. Whatever demagogues may way, you know in your hearts that you have only benefited from our work. But there were those in your midst who, form short-sightedness, d selfishness, have undermined the peace of this country, and have induced in the Royal Commission and the British Government the conviction that within the frame of the Mandate there was no room for cooperation between us.

The solution which the Royal Commission have devised and which the British Government has now adopted did not originate from us, but we have to face it as you have to face it. We are not returning to Palestine in order to dominate you. We do not come here as agents of any imperialist power nor with any imperialist design. We are the returning sons of this land. We want to rebuild it, ad you have seen that we are able to rebuild it for the benefit of all its inhabitants. We have to cooperate with you as you have to cooperate with us in the new phase which will now begin. We are not your enemies and have no designs against your peace and prosperity. But make no mistake about this: you cannot stand on your own feet unaided. You will not escape the influence of modern culture and progress. In this world of ours there is no room for those who stand alone. You need the power of development which the Jews bring with them. We bring it to you without any of those political designs which are generally associated with Western influence in this part of the world.

To the British I would say: whatever solution is now adopted the essential purpose of the Mandate must be safeguarded. That purpose is development, scope for new growth. Many of do not know what is happening here. To throw us to the dogs will not save your Empire. On the contrary it will undermine its foundations. Here is a unique chance of fostering the growth of a new society which will establish peace and progress in this part of the world. I we were not there, we would have to be invented in your interests and in the interests of this part of the world. The British have a reputation for having instinct for budding forces. Now is the time to show it. This thing is perhaps today the supreme test of British statesmanship, of its ability to foster new life, to help the rebirth of a nation, of a new society. Show that you can give a positive and creative reply to the destructive forces which are today harassing the world, a reply which will shame your enemies and will re-establish the glory of your great Commonwealth in the new phase which humanity is about to enter through the present crucible.