(March 1939)

Al-Husayni, Hajj Amin. “The Decision by Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husayni to reject the 1939 White Paper.” Izzat Tannous, The Palestinians Eyewitness History of Palestine. New York: Igt Co, 1988. 309-310. Print.

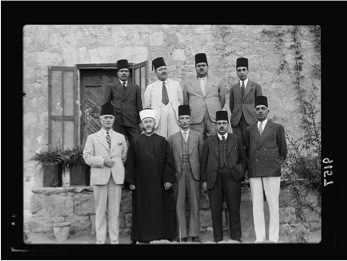

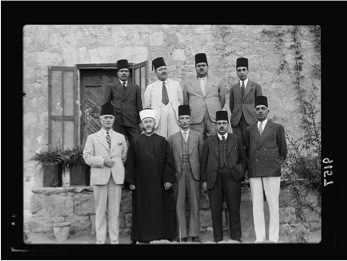

Dr. Izzat Tannous, an Arab Christian, headed the Arab Center in London, an organization formed to promote support for the Palestinian Arabs. In 1936, he was a supporter of the Mufti and a member of an Arab delegation to London. Palestinian Arab delegations went to London half a dozen times between 1920 and 1936 to protest the British policy of supporting the development of the Jewish National Home and to urge Palestinian Arab self-determination. According to British Colonial Secretary Malcolm MacDonald, Tannous “tended to be a moderate, therefore his influence in Palestine was not very great…he [was] a man capable of reason and some courage…whatever influence he may have had would be exerted on the side of peace.”

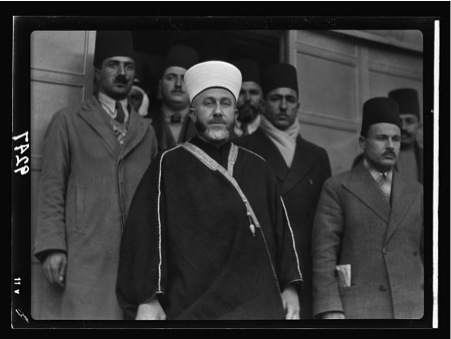

Tannous, like many of his Palestinian peers, vigorously opposed Zionism and the development of the Jewish national home; specifically, he opposed the British policy of promoting the 1937 partition of Palestine into separate Arab and Jewish states. In 1938, the British withdrew the partition idea as quickly as they had introduced it in the 1937 Peel Commission Report: it was deemed unworkable primarily because the Arab state would not have been viable and Arab leaders in surrounding states were clamoring for partition to be still-born. In its new policy statement on Palestine released in early 1939, Britain proposed to severely limit Jewish immigration and land purchase, and to establish a unitary state in Palestine that would come about within a decade. In such a state the Arab population would have become a majority and the Jews a minority. Tannous and all members of the Arab Higher Committee were in favor of accepting such a solution. The only dissenting and apparently important voice was that of Hajj Amin al Husayni, the Mufti of Jerusalem. The Mufti had enormous power in his hands, yet he chose non- engagement with the British. Furthermore, he chose not to take any political path that might sometime in the future compromise total and absolute Palestinian Arab control over all of Palestine. He did not want to consider sharing any present or future political power with any other Arab leader in Palestine, and he steadfastly opposed any Jewish presence in Palestine, even with minority status. For the Mufti, there simply was no place for the Jews or Zionists in Palestine. For the Palestinian Arabs, 1939 was a moment when active British policy and Arab state support for Palestinian national aspirations was at its peak. In the late 1930s, in the 1940s, and particularly from 1945-1948, British political leadership and the American State Department, especially the Near East section, vigorously opposed or sought to delay Palestine’s partition, which would have seen the creation of a Jewish state. Yet again, in this nine year period, as in 1939, Palestinian and Arab leadership chose emphatically not to engage in political discussions to secure either a federal state dominated by the Arab population, or a two state solution. Arab leaders consistently wanted an absolute guarantee that the Zionists would have no influence in determining Palestine’s future. As for those ‘moderates’ who wanted to consider a compromise with the British in 1939, they simply did not want to stand up in public against the Mufti of Jerusalem.[1]

Below, Tannous recollects the Mufti’s spring 1939 decision to reject the federal state solution, going against fourteen other Palestinian notables who favored the federal state solution idea. For more information, see Malcolm MacDonald’s “Discussion on Palestine” (August 21, 1938), which holds considerable detail of Tannous’s meetings with MacDonald in August 1938. See British Cabinet Papers 190 (1938) and Great Britain, Foreign Office 371/21863.

-Ken Stein, January 2012

The Arab Higher Committee and the White Paper

“As soon as the White Paper was published, the members of the A.H.C. (Arab Higher Committee) and all those Palestinians who attended the Palestine Conference in London gathered at Haj Ameen’s residence near Jouneh, the suburb of Beirut. The two Defense Party members, Ragheb Nashashibi and Yacoub Ferraj, were absent because they had resigned from the A.H.C. in 1937.

The Committee met every day and the White Paper was scrutinized in detail. We were fifteen in number. The Committee met for nearly three weeks. They were day-long meetings, only broken by generous luncheons served at Haj Ameen’s table.

The discussion was in a family like manner at first, sitting in a circle and all taking part. The morale was high and the expectation for a brighter future was higher. This went on for a time, dreaming of a Palestinian Arab as the head of a department, as a Minister or a Prime Minister or even at Government House, and why not? But this sweet dream did not last long. The discussion became more strained as some of us began to realize that Haj Ameen was not in favor of accepting the White Paper. This negative stand, which gradually became more pronounced, made the atmosphere extremely tense, The arguments between Haj Ameen and the rest of the members became acute and after a fortnight of discussion it became quite clear that the only person who was against accepting the White Paper was Haj Ameen Al-Husseini. The remaining fourteen members were not only strongly in its favor, but were determined to put an end to the negative policy Arab leadership had been adopting heretofore. “Take and demand the rest” was now their new motto. If there were excuses for our negative stands in the past, and there were, they were gone.

At this stage of the discussion, an atmosphere of resentment and dismay prevailed over the meetings and there was reason for it. The fourteen members knew very well that the acquiescence of Haj Ameen Al-Husseini was a very essential requisite and that without his blessing because of his magic influence on the Palestinian masses, the White Paper would not be implemented, a goal which the Zionists were madly seeking to score. Consequently, the sole concern of the Committee was now concentrated on convincing Haj Ameen that his negative stand was extremely detrimental to the Arab cause and was serving unintentionally, the Zionist cause,; and that he was doing exactly what the Zionists wanted him to do.

It is true that none of us could claim that the White Paper was a perfect political instrument without blemish; but at the same time; none of us could deny that it effected drastic changes in the despotic policy which had, so far, governed Palestine and that it had marked a decisive turning point in the history of Palestine. The fourteen members felt that they could not possibly discard a policy which had put an end to the Jewish National Home policy in Palestine; nor could they conscientiously refuse a policy which had cancelled the establishment of a Zionist State recommended by the Royal Commission and adopted by the British Government. And what right do we have to: discard a policy which stipulated that:

After the elapse of five years and the contemplated 75,000 immigrants have been admitted, H.M.G. will not be justified in facilitating, nor will they be under obligation to facilitate further development of the Jewish ‘National Home by immigration.

Did not this statement put an end to the development of the Jewish National Home and an end to the Balfour Declaration? And what gain do we, the Arabs of Palestine, expect to procure from discarding such a policy.

Another week of heated argumentation took place within the Committee with no tangible result. Haj Ameen kept repeating his arguments that the White Paper contained too many loopholes and ambiguities to be of any benefit; the “transitional period of ten years” was too long and the “special status of the Jewish National Home was too much of an ambiguity to be accepted. There were other objections he raised which space will not permit me to record; but, all in all, they were not important enough to permit the total discard of policy which gives us our major demands, put an end to our fears for the future and which our enemies simply crave to abolish!”

[1] Issa Khalaf, Politics in Palestine Arab Factionalism and Social Disintegration, 1939-1948, Albany, 1991, pp. 74-77.