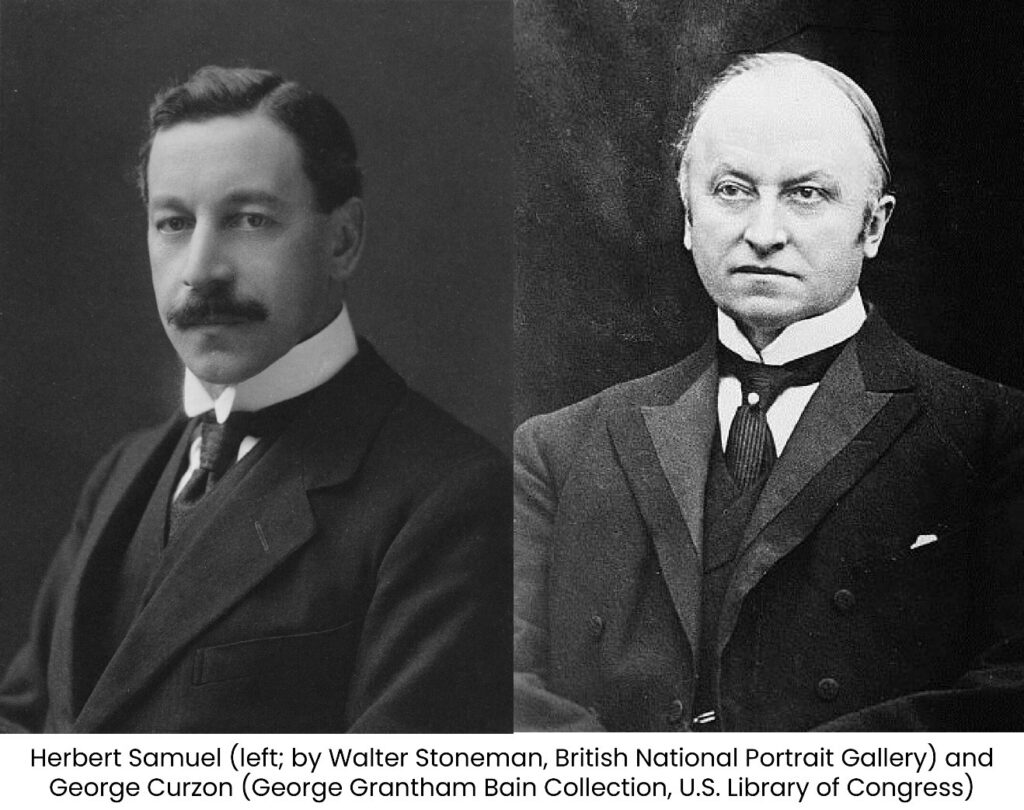

Sir Herbert Samuel, a review of present and future Zionist-Arab interactions in a report on Palestine to The Right Honorable Earl Curzon of Kedleston, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, London, April 2, 1920

Source: Herbert Samuel Files, Box 6, Israel State Archives, Jerusalem, Israel

Note: Herbert Samuel would be appointed the first of seven British High Commissioners to govern Palestine through the British Colonial Office from 1920-1948. He served from 1920-1925, and was the only Jew appointed to the position and the only High Commissioner not to have served in the military prior to his appointment. Like his successors as High Commissioner, he exercised absolute control over the political, executive, and judicial operations in Palestine, always with the consent of the Colonial Office, the Colonial Secretary, the Cabinet and ultimately the Prime Minister. Samuel’s tenure as High Commission had the greatest influence of the seven (Herbert Plumer, John Chancellor, Arthur Wauchope, Harold MacMichael, Viscount Gort (John Vereker), and Allan Cunningham) because he set the tone for governance. He allowed each community to develop independently, did not want to repress either, or fully understood Arab opposition to Zionism. The political impact of his evenhandedness evolved into what might be termed, “internal” or “institutional partition.” By doing so, the High Commissioner in Palestine became the umpire, referee and judge to both communities, tilting to and fro as local, regional, and international politics demanded. After visiting Palestine, he shared his views with the profoundly anti-Zionist Lord Curzon, just prior to his inauguration the British civilian administration in July 1920.

Curzon saw the Middle East as a strategic buffer to Russian penetration and notably two decades before the British and French agreed on their division of the Arab provinces of the former Ottoman Empire into Mandates (trusteeships- French in Lebanon and Syria and the British in Iraq, Palestine and Transjordan), Curzon actively promoted securing friendship treaties with Arab led Persian Gulf states as part of the British interest in linking Britain’s interest in Egypt (1881-1882) across the Middle East to Iraq the Gulf states and into Afghanistan and Persia. He served in India in the British Foreign Office in the 1880s through the early 1900s and was British Foreign Secretary from 1919-1924. There he oversaw the division of the British Mandate in Palestine with the establishment of the Emirate of Transjordan in 1921-1922, alongside Palestine, with London’s promise to establish the Jewish National Home.

A summary of Samuel’s observations appears here

On Arab political sentiment, jealousies prevent homogenous coordination “This nationalism (here) is not free from a strong religious element, and the nationalist teaching often assumes the form of hostility against the infidel. It would be difficult to ascribe to this movement any great political value. There is no political organization and no political leadership: the Arab families and tribes are much too divided among themselves and the jealousies between them much too pronounced. They are not welded together and do not form, at least at present, anything like a homogeneous body.”

Arab views toward Jews- motivations “The hostility against Zionism, which was so manifest six months ago, is due to various causes. Firstly, ignorance of Zionist aims and methods. The Arabs were repeatedly told that the Jews were coming in masses into the country in order to despoil them of their land and property. Naturally, they became enemies of the Jews. Some exaggerated statements in the Jewish press and speeches of extremists like Mr. Zangwill have also served to mislead the Arabs as to the real intentions of the Zionists and have done the Jewish cause in Palestine incalculable harm.

The second cause is also perhaps more economic than political and is chiefly applicable to the Effendis or large landowners. These people were in a privileged position during the Turkish regime. They controlled large numbers of fellaheen or peasants whom they bled white. They also formed in the time of the Turks the chief part of the administration and still continue to do so now under the temporary military British rule. It is not for me to criticize their administrative methods and habits. No doubt the Foreign Office is aware of these from the reports of its own advisers.) The establishment of the Jewish National Home would lead no doubt in the course of time to a considerable change in the personnel and methods of administration, and the Effendi feels his privileged position slipping away from him. He abhors all European methods, feeling that they would mean a reform of the political and economic abuses from which he profits. But the British being too strong for him to oppose openly, he seizes Zionism as a very convenient pretext in order to embarrass the British administration.”

“The Arabs were told that Jews were returning in great numbers to Palestine to which Jews had an inalienable claim; that Jews did not intend to swamp the country as that would lead to a catastrophe; that Jews were working for a well organized immigration ; that there was ample room in the land for Jews and for them and that the development of the country would inure to our common benefit. Jewish colonists receive daily numerous offers from landowners, big and small, and requests to come and buy property in various districts.”

The Land question “Palestine is at present very uneconomically cultivated. The Arab method of agriculture is primitive and extensive. With irrigation, modern roads, sanitary conditions, and the use of machinery and other methods of Modern farming, probably not more than one sixth of the land which at present is used by an Arab farmer would be required to yield a livelihood for a family accustomed to European standards. The power of the large absentee landowners, the oppressive system of taxation and the ignorance of the fellaheen combined to prevent a more economic use of the land under the Turkish regime. The incidence of taxation at present falls almost wholly on the gross yield of the land. The development of intensive farming, which entails comparatively heavy operating costs, is consequently discouraged, while no effective check is placed on the uneconomic use of the land and its retention solely for speculative gains.

Jewish education “The Zionists have given considerable attention to the development of a system of Hebrew education in Palestine; and under very difficult circumstances have achieved progress. Before the advent of the Zionist Organization into Palestine, there was no unified system of Jewish education. Every European Jewish community established its system of schools. These schools taught in the languages of their respective mother countries, and naturally became political advance guards of the various European powers. The national idea naturally militated against this disintegrating tendency and it found its practical expression in the one fundamental demand for a national system of schools with one language of instruction, which naturally was Hebrew. Out of 16,000 Jewish children who go to school in Palestine, 14,000 are at present in the Zionist schools, but even the remaining 2,000 who are still in other schools are forcing them to adopt Hebrew as the language of instruction. This does not mean that there is an antagonism towards the European languages on the contrary, the Palestinian young generation speaks European languages with great ease. Particularly since the occupation of Palestine by the British, the children have been most eager to learn English. But the Palestinian child receives its fundamental training and education in Hebrew just as the English child receives its training and education in English.”

Possible future population of Palestine – “The density of population in the hilly Lebanon, only one eighth of the area of which is cultivated, in approximately160 inhabitants per kilometer. In Palestine it is approximately 25. If one assumes the Palestine may become no more densely populated than Lebanon, there is room for another 135 inhabitants per kilometer. Assuming the proper boundaries for Palestine, it would contain approximately 30,000 square kilometers, and could support a population of 4,000,000 people. If one takes into consideration that the trans-Jordanian plains are almost empty, that at present it is practically no man’s land, and that it is very fertile and crossed by numerous streams, these estimates appear to be rather conservative.”

— Ken Stein, August 5, 2024

Sir Herbert Samuel Report on Palestine to the Right Honorable Earl Curzon of Kedleston, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, London, April 2, 1920

April 2, 1920

The Right Honorable Earl Curzon of Kedleston, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs,

London

My Lord,

I hope you will find the enclosed report on our work in Palestine of some interest and use. It is my present intention to return to Palestine the end of February with the hope of initiating the program of actual work therein outlined. I am particularly anxious, as I have already had occasion to inform Your Lordship, that Dr. Arthur Ruppin who is perhaps the foremost authority on Palestine should accompany me. I am sure that his services would be most invaluable, and I hope that his going will meet with your approval.

I am, My Lord,

Your most obedient Servant,

(Signed) Herbert Samuel

Paris

April 2, 1920

The Right Honorable Earl Curzon of Kedleston, K.G., F.R.S.,

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs,

My Lord,

Supplementing my conversation with Your Lordship last week, I beg to submit for your consideration the following observations respecting Palestine.

THE ARAB POSITION IN PALESTINE

It is not easy to give a clear account of the Arab position in Palestine. It is difficult to distinguish what is a particularly Palestinian manifestation and what is a repercussion of happenings in Egypt and Syria. There is certainly an intimate connection maintained between Jerusalem and Damascus, and Jerusalem and Cairo. Many Palestinians, especially from Nablus, have entered the services of the Sheriff and have become officers in the sheriffian army. Sheriffian and Turkish Agents are coming through Palestine on their way to Egypt and Bedouins from the desert are coming into Palestine, and so effervescence and agitation constantly goes on and is maintained. Rumors spread with great rapidity throughout the country, in most cases in an extremely exaggerated form.

In Palestine itself there are some clubs and circles consisting chiefly of young men in which nationalist ideas are preached and fostered. This nationalism is not free from a strong religious element, and the nationalist teaching often assumes the form of hostility against the infidel. It would be difficult to ascribe to this movement any great political value. There is no political organization and no political leadership: the Arab families and tribes are much too divided among themselves and the jealousies between them much too pronounced. They are not welded together and do not form, at least at present, anything like a homogeneous body.

The hostility against Zionism, which was so manifest six months ago, is due to various causes. Firstly, ignorance of Zionist aims and methods. The Arabs were repeatedly told that the Jews were coming in masses into the country in order to despoil them of their land and property. Naturally they became enemies of the Jews. Some exaggerated statements in the Jewish press and speeches of extremists like Mr. Zangwill have also served to mislead the Arabs as to the real intentions of the Zionists and have done the Jewish cause in Palestine incalculable harm.

The second cause is also perhaps more economic than political and is chiefly applicable to the Effendis or large landowners. These people were in a privileged position during the Turkish regime. They controlled large numbers of fellaheen or peasants whom they bled white. They also formed in the time of the Turks the chief part of the administration and still continue to do so now under the temporary military British rule. It is not for me to criticize their administrative methods and habits. No doubt the Foreign Office is aware of these from the reports of its own advisers.) The establishment of the Jewish National Home would lead no doubt in the course of time to a considerable change in the personnel and methods of administration, and the Effendi feels his privileged position slipping away from him. He abhors all European methods, feeling that they would mean a reform of the political and economic abuses from which he profits. But the British being too strong for him to oppose openly, he seizes Zionism as a very convenient pretext in order to embarrass the British administration.

A third reason is the presence in Palestine of numerous agents of great European powers who try to influence the population. It is interesting to note that foremost amongst the powers which display a considerable, and a somewhat dangerous, propaganda are the Italians. In that connection one should remember that in Palestine the Vatican and the secular Italian Government seem to be identical. The cleavage which exists in Rome is not apparent in Jerusalem; almost every religious order, particularly the Franciscans, are at the same time political agents. The ABanco di Roma@, which is a Vatican bank, is trying even under the present military law to create vested interests in Palestine, by methods which cannot always be considered as the very best. The French propaganda has also been active and extensive, although recently, especially since the occupation of Syria by the French, it has abated and is likely to diminish still more in the future if a settlement of the Anglo-French relations in the Near East is not unduly protracted. All these foreign influences operate on the population of Palestine and keep it in a state of unrest. They all appeal to its national and religious instincts and they all make use of Zionism as a weapon against England, and there is no doubt the anti-Zionist and anti-British propaganda amongst the Arabs run parallel.

One place in Palestine occupies a somewhat particular position, both in its attitude to Great Britain and to Zionist policy, that is Nablus. Nablus is very powerful economically. The prosperity of Nablus is based chiefly on the olive tree and the industry connected with the production of oil and soap. The chief argument against Zionism of the people of Nablus is that Zionism may build modern factories and so compete successfully with their oil industry. One important agitator based his opposition against me particularly on the ground that I was a chemist and probably had the intention of making soap in Palestine.

Nablus is also a powerful center not merely of Mahommedan but of Turkish influence. Extensive communications are established between Nablus and Mustapha Kemal. Large stores of arms and ammunition are accumulated there. Through the cooperation of the Zionist Intelligence service several thousand bombs and rifles of German origin were recently discovered in Nablus.

The feeling in Nablus against the Jews, unlike in other parts of Palestine, is of long standing. NO Jew has lived in Nablus or the neighboring towns of Tulkarem and Qalqilya for centuries. The Anti-Jewish feeling is due in on small measure, I believe, to the ancient Samaritan Community which still dwells in Nablus and still retains its belief in the animosity between Samaritans and Jews which was supposed to exist in Biblical times. These ancient prejudices will, however I am convinced, disappear in time when the Samaritans see what help the Jews can be to them. I have been in very close touch with their High Priest, unfortunately a man of not a very attractive personality and not entirely reliable and trustworthy. As a result of our conferences, however, certain members of the Samaritan community presented to the Zionist Commission a number of requests for assistance, including a request for the establishment of a school with Hebrew teaching. The most interesting request, perhaps, was that the Zionist Commission should use its influence with the Jewish community of Jerusalem so as to induce Jewish girls to marry Samaritan young men. The Samaritan Community has hitherto never concluded any marriages outside their own circle. Inter-marriage would take place, it would certainly contribute greatly towards the establishment of an entente between the Jewish community and the Samaritans, who would in their turn use their good offices in order to pacify the Arabs. It is of course difficult to break down prejudices which have been persisting for about thirty centuries, but from a political point of view it is very desirable that the Jewish community should give increased attention to the welfare of the Samaritans. The Zionist Commission is at present engaged in setting up a school and sending down some teachers and also a relief agent.

Various Arab notables of Nablus visited me and amongst other things asked me to set up a bank in Nablus which would give long term credit on mortgages. That is a distinct change for the better as compared with six months ago when an attempt to establish a branch of the Anglo-Palestine Company in Nablus met with considerable hostility. I also visited Qalqilya and Tulkarem, and outwardly at any rate, the reception was most cordial. It would be erroneous to suppose that these signs of oriental cordiality denote a deep change in the Arabs’ attitude but one is driven to the conclusion from the experience one gathers in the country that the Arab hostility should and can be met by a frank, honest and bold policy. The Arabs were told that Jews were returning in great numbers to Palestine to which Jews had an inalienable claim; that Jews did not intend to swamp the country as that would lead to a catastrophe; that Jews were working for a well organized immigration ; that there was ample room in the land for Jews and for them and that the development of the country would inure to our common benefit. On the whole such a statement is taken by the Arabs in a friendly spirit. They are suspicious, perhaps critical and therefore I think that mere propaganda on the Jew’s part would not help matters. It is only through the beginning of actual work in Palestine and the association with that of the Arabs with that work that we can hope to remove completely their suspicion and distrust.

It should be remembered that Arab hostility towards Jews and Zionists is a product of comparatively recent development. And Arabs know the general tendencies of Jewish colonizing activity and understood that it meant more to the Jews than the mere building up of a few villages. They always expected that there would be a time when Jews would be coming into the country in great numbers, still they never showed any hostility to Jewish colonies; on the contrary, the relations between the colonists and their Arab neighbors were cordial. And even now a great many of our colonists have numerous connections with the Arab world, especially among the fellaheen who always come to them for advice and guidance. The case of the Jewish colony Metullah is interesting as an illustration of this. Metullah, which is at present in the French sphere (we trust only temporarily), is a Jewish village placed almost at the foot of the Hermon rather away from the rest of the Galilean Jewish colonies. It is surrounded by a very mixed population of Arabs, both Christian and Mahommedan, Druses, Circassians and some Turks. There has never been any trouble between the colonists and their neighbors. The colonists are even now in this troublesome period the only Europeans who can go about unmolested in the remote trans-Jordanian districts of the Hauran and Jaulan. Jewish colonists receive daily numerous offers from landowners, big and small, and requests to come and buy property in various districts. Metullah has recently become a center of disturbance but that is due entirely to friction between French and Arabs. One notices the tendency of certain French agents to try and represent the trouble in Upper Galilee as Arab hostility against the Jew, but the facts belie this contention. The British political officer, Colonel Waters Taylor, had an opportunity to watch and study from Haifa the conditions in North Galilee, and he would bear out this statement fully. I went over the whole of the Litany district, visited Metullah and had ample opportunity of investigating the position. One could not notice any trace of hostility against the Jews. It was only the arrival of a small French garrison into Metullah and the attempt of the French to occupy Hasbeiya dn Rasheiya, two great Arab communities, which provoked the populations. Bedouins attacked Metullah and their leaders informed us this attack was directed against the French and not against the Jews. From many facts and observations gathered in the country one is driven to the conclusion that the hostility to Jews and Jewish aims is artificial, brought about by agencies working in the dark, operating against Great Britain=s position in the East. These agencies assume very different aspects. They assume the guise of Egyptian, Arab, or Turkish nationalisms, they sometimes utter Bolshovik threats. These dark forces of destruction work on the imagination of the primitive Bedouin, incite him to brigandage, pillage an even murder. These forces will develop as long as these political conditions in the Near East remain undefined. It is the duty of the Zionists in Palestine to take the Arab movement seriously and to try and establish friendly relations with the Arab community on t a basis of honest cooperation. This is possible and a great service would be thus rendered to the cause of civilization in the Near East.

THE LAND QUESTION

The land question is a crucial one. The Jewish National Home will be rooted in the soil and grow up about a sturdy Jewish peasantry. The improvement of the present poor state of the Arab fellaheen also depends largely upon a proper handling of the land question.

Palestine is at present very uneconomically cultivated. The Arab method of agriculture is primitive and extensive. With irrigation, modern roads, sanitary conditions, and the use of machinery and other methods of Modern farming, probably not more than one sixth of the land which at present is used by an Arab farmer would be required to yield a livelihood for a family accustomed to European standards. The power of the large absentee landowners, the oppressive system of taxation and the ignorance of the fellaheen combined to prevent a more economic use of the land under the Turkish regime.

The incidence of taxation at present falls almost wholly on the gross yield of the land. The development of intensive farming, which entails comparatively heavy operating costs, is consequently discouraged, while no effective check is placed on the uneconomic use of the land and its retention solely for speculative gains. In the interest not only of Jewish colonization by the Arab peasant as well, the system of taxation must be thoroughly revised. Measures will have to be taken like in Egypt and the Sudan which will tend to throw the incidence of taxation on the unimproved value of land, so as to encourage the cultivator to improve his holding and increase its productivity. Such measures would automatically tend to the breaking up of the large latifunda in so far as they have no economic basis and would doubtless bring into the market considerable quantities of land required for colonization . The entire question of taxation particularly in so far as it relates to the land, is of great importance and should receive immediate attention by experts.

The present uncertainty of land titles is likewise a serious impediment to economic progress, both from the Arab and Jewish point of view. A cadastral survey is essential for the prevention of tax evasion and as a basis for taxation reform. So long as the uncertainty of land titles exists, it will be difficult for the Zionists to take effective steps to acquire considerable areas of either public or private lands. One of the first measures required to facilitate the Zionist program and to lay the necessary basis for the economic development of the country therefore is a cadastral survey.

Taxation reform and a cadastral survey would make for the improvement of the economic welfare of the country and incidentally tend to bring land into the market for Jewish colonization. But it is doubtful whether these measures would be adequate in themselves to make sufficient land available for Jewish settlement at a reasonable price, i.e., a price bearing any relation to the productive value of the land or at all comparable to the price paid for similar land in other countries. The Zionists would have to rely on more direct measures to secure access to the land. From the point of view of national economy, a great deal could be said in favor of the compulsory breaking up on a basis of reasonable compensation of the large latifundia which are wastefully cultivated and in favor of settling Jews upon them, after first providing, of course, for the needs of the present tenants. It would, however, probably be politically unwise for the Zionists to press at the present time for such measures, which might provoke hostility upon the part of the landlords and lead to the intentions of the Zionists being misinterpreted to the people. There are, however, large quantities of state lands, waste and unoccupied lands in Palestine, and it seems to me only right and proper that these should be turned over to the Zionists upon reasonable terms and conditions for the purpose of colonization and development. Of course, the Zionists would have to make satisfactory provision for the comparatively few tenants who are now dwelling on such lands.

PUBLIC WORKS

I shall attempt only to touch upon a few of the main types of public works which should be carried out in Palestine in the nearest future. My remarks should be supplemented by reference to the attached report of Sir Charles Metcalfe and Sir Douglas Fox, Ltd., which deals with a number of projects of public works and which was drawn up after a technical inspection and survey of the country extending over several months.

Foremost among the public works which will have to be undertaken are those connected with drainage and sanitation. The prevalence of malaria stands in the way of any organized immigration. The vitality of the immigrants would be sapped and their life imperiled by the malaria mosquito. The drainage of the marshes is of course the only thorough way to combat malaria all other sanitary measures simply serve as a palliative and do not eradicate the causes of the disease. The number of marshes to be drained is relatively small, and this work should be begun immediately.

The most important district is the lake of Huleh to the north of Tiberias. The drainage of the Lake of Huleh would have a triple advantage: Firstly, it would get rid of the greatest center of infection; secondly, it would wet free a large tract of very fertile land; and thirdly, it would make available for irrigation the waters of Merom, which are at present a source of disease, thereby increasing the fertility of the neighboring district perhaps tenfold. It is the opinion of competent engineers, both British and Jewish, including the head of the Department of Public Works of the British administration, that the drainage of the Huleh could also yield a very considerable quantity of power which could be utilized for pumping the waters needed for irrigation upon the surrounding plateau.

Another important project is the drainage of the Jordan Valley. Here again a vast district, which, if freed from Malaria, could produce splendid crops and feed a population of perhaps 500,000 souls, is ling waste. Parallel with the draining of the Jordan Valley would proceed the irrigation of and the establishment of settlements on the adjacent hills.

While it would probably be unwise to undertake large irrigation schemes at present, local irrigation from underground waters, springs and streams can now be develop4d to advantage for this, however, power will be required. Assuming Palestine obtains her proper boundaries on the north, sufficient power can be developed from the Litany, the Jordan and the Yarmuk for irrigation, milling and other industrial enterprises closely associated with the agriculture of the country, although power is never likely to be abundant in Palestine and the economic life of the country must always be primarily agricultural. The development of power from the falls of the Jordan between the lake of Merom and the lake of Galilee could in the opinion of the Department of Public Works of the British Administration, be undertaken at once.

The establishment of a harbor in Haifa, which is destined to become the leading port of Palestine and the neighboring countries, would also receive early attention. Contrary to the usual projects, however, I should not contemplate the immediate erection of extensive facilities but should establish at first only modest accommodations for two or three ships, as the trade of Haifa and the surrounding district is not yet sufficiently developed to justify at present the building of a costly modern harbor with all the necessary appliances. More extensive facilities can be provided as the commerce of the country grows and develops. The views of the present Administrator of Ports in Palestine on this subject coincide with mine.

I am pleased to find that comparatively little seems to be required in the way of the further development of the present network of roads and railways, except for a system of narrow gauge railways to link together the main trunk lines. The military authorities have built a splendid series of roads and railways, which should be sufficient to meet the economic needs of the country for some time to come. Unfortunately, however, the present service of maintenance and repair stands in urgent need of reorganization.

A few remarks should be made on the future of the railway from Qantara to Lod. This railway at present is run at a loss of approximately 500,000 pounds a year. In the opinion of experts like Sir Charles Metcalfe, the losses could be greatly reduced under a different system of management. But even under the best conditions there is very little prospect of the railway yielding a return, unless a through service could be maintained between Cairo and Jerusalem which would avoid the change from Qantara West to Kantara East. For that purpose, the swinging bridge over the Suez Canal would have to be opened up definitely for railway traffic. A considerable part of the tourist and pilgrim traffic would then travel on this route and the railway possibly could become self-sustaining. Otherwise, it would always remain a burden to the British Government, which would probably want to maintain the railway for strategic reasons. It would seem in any event a pity to tear up about two hundred kilometers of well laid track.

Finally, a very important branch of public works urgently requiring consideration is the afforestation of Palestine. The hills and the sandy dunes do not lend themselves to agricultural purpose in the ordinary sense of the word, but it is sufficient to observe what has been done in hilly and rocky districts between Nablus and Jerusalem and on the road between Jerusalem and Jaffa, to be convinced that there are vast possibilities, even on these hills which for centuries have been devastated, and which under the influence of winds and heavy rains have become more and more disintegrated B the rocks break up and cover the plains of Palestine with rolling stones and so import to the whole landscape an aspect of extreme desolation. The dunes are in fact eating up the fertile part of the maritime plain. One can measure the progress of the dunes and the devastation of the plains ever year. There is therefore pressing need that measures should be taken to stop this progress of desolation and convert this waste land into a source of wealth for the country.

In the opinion of competent experts, and this opinion is supported by actual experiment which ranges over a number of years and in different parts of the country, the hills could be covered with at least three sorts of trees; the olive, the pine tree and the carob tree. There is no need to dwell on the possibility of growing olive and pine trees. The wealth of Nablus and vicinity comes from the hills whose flanks are covered with magnificent olive groves. There is no reason why similar olive groves should not be planted on the barren hillsides all over the country. The same is true of the pine tree, particularly of the maritime pine. The carob also grows wild in Palestine, and one sees luxurious and shapely trees breaking out of rocks spontaneously all over Palestine and Syria. If the growth of these trees is developed systematically, they not only will protect the hills from further disintegration and will give Palestine abundant shads, of which it now stands sorely in need, but they will produce large quantities of cattle food. The carob particularly is perhaps the best cattle food known. Groves of carob would form the basis of an extensive cattle culture and all that is connected with it, and make the country again flowing with milk, if not honey. Here as elsewhere many a circumstance which tends towards making Palestine uninhabitable at present could be converted into a source of wealth and strength to the country. It only needs the hand of man, capital, intelligence and energy.

EDUCATION

I may be permitted to touch upon the subject of education which is most important from the Zionist point of view. The Zionists have given considerable attention to the development of a system of Hebrew education in Palestine; and under very difficult circumstances have achieved progress. Before the advent of the Zionist Organization into Palestine, there was no unified system of Jewish education. Every European Jewish community established its system of schools. These schools taught in the languages of their respective mother countries, and naturally became political advance guards of the various European powers. France, for instance, established an influence in Palestine through supporting the Alliance Israelite Universelle, and French influence spread in Palestine through the medium of the Jewish schools. When Germany entered into competition with France for the hegemony in the Near East, she encouraged the activities of the Hilfsverein Deutscher Juden in Palestine, which created a system of schools with German as their language of instruction. The Anglo-Jewish Association established the Evelina de Rothschild’s school, with English as the medium of instruction. And so, Palestine, and particularly Jerusalem, became a veritable tower of Babel. The Jewish community was the dumping ground of political intrigues, jealousies and rivalries. Needless to say, that this variety of systems did not render the children fit for remaining in the country, but on the contrary turned the eyes of the more ambitious among them to the countries they were taught to look upon as their mother lands. The national idea naturally militated against this disintegrating tendency and it found its practical expression in the one fundamental demand for a national system of schools with one language of instruction, which naturally was Hebrew. Out of 16,000 Jewish children who go to school in Palestine, 14,000 are at present in the Zionist schools, but even the remaining 2,000 who are still in other schools are forcing them to adopt Hebrew as the language of instruction. This does not mean that there is an antagonism towards the European languages on the contrary, the Palestinian young generation speaks European languages with great ease. Particularly since the occupation of Palestine by the British, the children have been most eager to learn English. But the Palestinian child receives its fundamental training and education in Hebrew just as the English child receives its training and education in English.

The educational budget per capita is the highest in the world. Owing to this rapid development of education it has been found necessary to proceed with the setting up of higher schools like a technical college and a university.

POSSIBILITIES OF PALESTINE

It is true that Palestine has no great mineral wealth or great natural resources, but it is equally true that Palestine is rich in sun and in water (the yearly rainfall in Jerusalem is equal to that of Manchester), both of which can be utilized to produce out of the soil of Palestine, if not wealth, moderate prosperity. It is from the Zionist point of view happily a country which does not lend itself to the making of big fortunes but will yield a respectable return only for hard and honest work. With the preparation and cultivation of the land and the construction and maintenance of public works, employment for a large number of people should be provided. It is the opinion of experts that, even without great technical development, there is room in Palestine at present for at least three million people without in any way encroaching upon the rights of the present population. A little reflection will show that this is not at all paradoxical. The Southern Jewish colonies were established under Turkish rule about 20 or 25 years ago by people who had no agricultural training, no agricultural traditions and who were typical town dwellers. The colonies were established under a government which put every obstacle in their way. They experienced practically every difficulty imaginable. The acquisition of land was not allowed. The Jewish pioneers had to buy their land somehow and somewhere. They naturally were not in a position to select the most suitable tracts. Yet, in the course of thirty years they have transformed their sandy patches into flourishing gardens and one sees the Jewish colonies standing out as cases in the midst of sandy desert. Rishon, for instance, possesses about two and a half square kilometers of land and on this comparatively small stretch live 3,000 people. It is obvious that the density of population possible in Palestine is far above what is usually estimated. There is no reason why all of the maritime plain of Sharon should not be covered with colonies like Rishon.

The density of population in the hilly Lebanon, only one eighth of the area of which is cultivated, in approximately160 inhabitants per kilometer. In Palestine it is approximately 25. If one assumes the Palestine may become no more densely populated than Lebanon, there is room for another 135 inhabitants per kilometer. Assuming the proper boundaries for Palestine, it would contain approximately 30,000 square kilometers, and could support a population of 4,000,000 people. If one takes into consideration that the trans-Jordanian plains are almost empty, that at present it is practically no man’s land, and that it is very fertile and crossed by numerous streams, these estimates appear to be rather conservative.

Mention should be made also of the possibilities of trade and industry. With the harbors of Haifa, Gaza and Jaffa, Palestine should enjoy much of the trade of the hinterland of Syria and Arabia. It should become the point of transit between Mesopotamia and Egypt, when the Haifa-Damascus railway is extended to Baghdad. Trade communications should be maintained with the ports of the Black Sea, as the Jews coming from Russia, Romania, and other Balkan States, would naturally retain their connections with those countries. There should also be room for certain industries in the country itself, like silk weaving, carpet making, glass, oil, soap, and all industries connected with agriculture, like the preservation of fruit, jam making, wine, etc. Finally, the chemical deposits in and about the Dead sea should afford the basis of a considerable chemical industry.

COLONIZATION AND DEFENCE OF TRANSJORDANIA

I should like to add a few words on the subject of the maintenance of law and order in Palestine, particularly in Eastern Palestine, during the period following immediately after the publication of the mandate. I had many opportunities of discussing the question with the competent authorities in Palestine. It is generally thought that during the next two or three years, especially if the fermentation in Egypt and Syria continues, a small army of occupation will be needed in Palestine, which may gradually be replaced by a militia or gendarmerie recruited locally and under British guidance and tutelage. But the weak point in such a scheme centers about the defense of Transjordan. The eastern frontier of Palestine is always open to the inroads of Bedouin tribes and it can only be nationally defended through the planting of a settled Population in Transjordan. Already the Turkish Government tried to meet the Bedouin danger by founding Circassian villages, especially in the northeastern part of Palestine. As the vast unpopulated plains of Transjordan are particularly suitable for agricultural settlements and have in the past served as the granary of the whole of Syria, it would seem from every point of view desirable to bring into these districts Jews from Transcaucasia who are capable soldiers, good agriculturists and who have maintained for centuries a pure Hebrew tradition. Their number is about 60000 to 70,000 and from numerous letters and petitions which reach us at present they are all ready to emigrate. During my stay in Palestine two representatives of these Jews arrived there having made their way on foot from Pagheston. Such people would form a most valuable nucleus for the colonization and defenses of Transjordan.

IMMEDIATE PROGRAM

What is now required above all else in Palestine is the beginning of actual work. In many respects, there has been too much talk from all quarters. The starting of concrete work is bound to relieve the political situation from both Arab and Jewish point of view. For all practical purposes it may be accepted as a fait accompli the Palestine is to be placed under a British mandate and to be reestablished as the Jewish National Home. With the cooperation and under the supervision of His Majesty=s Government the Zionist Organization can now quietly and unassumingly begin its constructive work.

A modest program has been prepared by the Zionists with the help of experts and this has met with encouragement from Lord Allenby and the administration in Palestine as is evidenced from letters annexed to this report. We are prepared to initiate this program at once. It calls for the improvement and extension of a number of the existing colonies and the preparation of the soil looking towards the establishment of new settlements, particularly upon tracts of the state domains. It includes an extensive housing program, as at present the dire lack of accommodations stands in the way of even a most restricted immigration. The erection of 1000 houses in various parts of the country would be insufficient to meet the demand of the coming year. Our housing program will require the setting up of a number of factories to manufacture and prepare bricks, tiles, slabs, and other building materials.

The Zionists are also prepared to undertake experiments in the afforestation of the hillsides and the planting of the dunes as soon as the necessary stretches of hills and dunes are placed at their disposal.

As the malaria swamps must be drained at once, if the Government is not prepared to carry out this most urgent public work, The Zionists would also undertake to do it under arrangements which would enable them to acquire the land reclaimed.

The magnitude of the Zionist work in Palestine is not to be underestimated. Already the Zionist budget which is now used mainly for education, agricultural experimental work and sanitation, almost equals that of the British Administration and it will be greatly increase as soon as the possibility of constructive work becomes a reality.

But the Zionists cannot carry through their program without the full hearted cooperation of the Government. In order to restore more normal conditions in the country and to make it possible for the Zionists to undertake the contemplated reconstruction, the following measures in my humble judgment, should be taken at once by His Majesty=s Government.

I. The enactment of the Land Ordinance which was submitted to his Majesty=s Government some time ago by the Chief Administrator with the approval of the Chief Political Officer.

This ordinance would modify the present prohibition of land transfers and permit small stretches of land to be transferred under proper conditions. The embargo was necessary during the war to prevent illicit transactions and harmful speculations in land, but its usefulness has now ceased. It is crippling the economic life of the country and causing great hardship. Unrestricted dealings in land would almost be preferable to the present all-embracing embargo which prohibits even the most legitimate and necessary transactions.

The land ordinance proposed by the administration does not permit all transactions in land but endows the authorities with powers adequate to prevent speculation and abuse. It permits in a limited degree transfers necessary to the resumption of the normal economic life of the country. It would enable the peasants and small proprietors to obtain credit upon their land. It would enable the Zionists to obtain small tracts of land and to start their building program. It would allay the unrest and suspicion which springs from the present static and abnormal economic state.

II. The appointment of a land commission for the following purposes:

(a) To make a cadastral survey.

(b) To revise the present system of taxation so as to encourage the close settlement and intensive cultivation of the land and discourage its uneconomic use or non-use.

(c) To arrange terms and conditions under which state, waste and other lands over which the state may possess the power of disposal should be turned over to the Zionist Organization for colonization and development, the rights of the present cultivator of such lands being equitably safeguarded.

The making of a cadastral survey has been greatly simplified by modern improvements in the art of aero-photography. One of the leading experts and inventors in this field is now in Palestine and the Zionists would be pleased to place him at the service of the Government. He has with him the most modern photographic appliances and equipment and would be prepared to undertake this work at once.

III. The modification of the present restrictions upon immigration.

The Zionists fully appreciate the danger of Jews coming into Palestine more rapidly than they can be absorbed into its economic life. The presence of a large idle and unemployed body of Jewish immigrants in Palestine would not advance the Zionist cause. But the gates cannot be kept closed forever, and the sooner regulated immigration is allowed the easier it will be for the Zionist Organization to allay the growing impatience of the masses and to control the flow of immigration in the future. There is no reason why expert and technical men desiring to familiarize themselves with the conditions and possibilities of the country, business men contemplating establishing productive enterprises in the land, and other people who in the judgment of the Zionist Commission would be likely to find productive employment and not become charge upon the community, should not be permitted to enter Palestine. It is believed that the present military administration might be quite prepared to accept the recommendations of the Zionist Commission in this matter. With the consent of His Majesty=s Government there should be no difficulty therefore in working out a policy of immigration along the lines suggested.

IV. The drainage of malaria-breeding swamps.

As already indicated the only effective way of combating malaria, which is the curse of the Country, is through the drainage of the swamps. The American Medical Unit is doing great constructive work in fighting malaria, but the more active cooperation of the Government in the drainage of the swamps is required. If the Government is not prepared to do this work directly, the Zionists, as stated above, would undertake to do it under arrangements which would enable them to acquire the land reclaimed.

V. The placing of stretches of dunes and hills at the disposition of the Zionists for experiments in afforestation.

In order to enable the Zionists to carry out contemplated experiments in afforestation on a larger scale than has heretofore been possible, suitable arrangements should be made to place at their disposition stretches of dunes and hills.

VI. Reforms in the Administration.

The Administration in Palestine is at present, with the exception of a few head officials, almost solely Syrian. The recruitment of more British and Palestinian Jews in the personnel of the post office, railways, and other administrative offices would, in my judgment make for increased efficiency and a better spirit de corps.

I am conscious that this report is not entirely unbiased. The Zionist idea is so much a part of my being that it naturally must influence my judgment. But I have tried, however, as far as possible to have my conclusions confirmed by trained experts and corroborated by the British authorities on the spot. It is now more than ever my firm conviction not only that Palestine will prove the best means of solving as a part of the world’s peace the difficult and far-ramifying Jewish problem but that it will as the Jewish National Home prove a source of strength and satisfaction to its mandatory.