January 17, 1930

Cabinet Papers 108 (1930)/file 20835; also found in Great Britain, Colonial Office files, CO 733/183/77050, Part 1

Sir John Chancellor was the third British High Commissioner in Palestine. He served from 1928 to 1931. When he began his tenure, he had no particular positive or negative attitude towards the Zionists or Arabs. By the end of his three-years of service, however, he was staunchly pro-Palestinian Arab to the point where he wanted the Jewish National home stopped in its tracks. He grew to believe that there “was bitter hostility of the Arabs in Palestine for the Zionists.”

In great detail, Chancellor expressed his anti-Zionist or more specifically pro-Arab views in this January 17, 1930, dispatch. Some ninety pages in length, it is the longest known dispatch from a High Commissioner in Palestine seeking a drastic policy change.

Chancellor came to view the concept of a Jewish national home as unjust to the interests of the local Arabs, and a detriment to the British Empire, where it had geopolitical interests with many Muslim Arab states and leaders. During his tenure in Palestine, major communal Arab-Jewish riots occurred in August 1928 and August 1929. They forced him to look at what caused those disturbances. Chancellor’s pro-Arab views evolved into influencing the conclusions of major investigatory reports that analyzed economic causes underlying Arab unrest in Palestine: Shaw Commission (1929), Hope Simpson Commission (1930) and Johnson-Crosbie Report (1931).

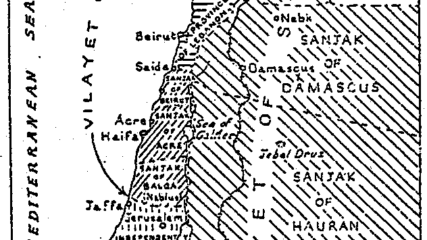

These reports concluded in one way or other that the growth of the Jewish national home was a threat to tranquility in Palestine. He took the view that there was no more open land available for Jewish development, contrary to the Zionist view that with increased economic investment extensive agriculture could be shifted to intensive farming, thereby supporting a larger overall population. Chancellor, however believed that the impoverished and severely indebted Arab peasantry needed to be protected against becoming landless. Chancellor believed that Arab agricultural workers might increasingly be turned off their lands and become an immediate threat to lawlessness. Chancellor recognized that the growth of Zionism (Jewish land purchase and Jewish immigration) was almost unstoppable because of the unrelenting Jewish unrelenting drive to build a national home. He realized also that there was a pervasive inability of Arab leadership, and often unwillingness to thwart Zionist development privately because significant numbers of Arab leaders were deeply engaged in land sales or in collaboration with the Zionists in other ways to benefit themselves individually. Fragmented Arab political leadership was caused in part by being tied to villages, localities, and sometimes adopting a narrow focus on personal rather than a ‘national’ well-being.

Chancellor made the case that it was the British who had to protect the Arab population against displacement. His paternalism for the Arab population was evident and Zionist leaders like Yehoshua Hankin, Josef Weitz, Chaim Arlossoroff realized the severe threat that Chancellor’s views posed. By the middle of 1930, Chancellor persuaded the Colonial Office to issue the October 1930 Passfield White Paper reflecting the need to slow down Jewish growth. While the Colonial Office issued the 1930 White Paper was rescinded, with Chancellor’s outlook against Jewish growth not fully implemented in the 1930s, the goals of the 1930 Passfield White Paper, namely limiting Jewish immigration and halting Jewish land purchase were eventually applied against the Zionists in the 1939 White Paper. By then, another had decade passed where the Jewish national home grew enormously in terms of organizational, demographic, and physical growth.

He enumerated why the Arabs in Palestine were so vexed, and what should be done to assist them. He pointed to Arab grievances but he also knew full well that the Arab community, its leadership and majority peasant population could not and would not withstand the Zionist commitment to build a state. He persuaded his colleagues in Palestine that the Balfour Declaration and the 1922 League of Mandate that governed British policy were not in broader British Middle Eastern political interests.

Specifically, Chancellor suggested that immigration and land purchase be curtailed. Short of stopping Zionist growth entirely in the 1930-31, Chancellor’s ideas spawned the application of half of dozen laws and regulations aimed at keeping keep Arab peasants on the land they worked. He had the Palestine administration pass a law to prevent Arabs from being displaced through collusive mortgage debt forfeiture between an Arab seller and Jewish buyer; he removed loopholes in the existing agricultural tenant protection laws (so they would stay on lands they worked and perhaps refuse compensation to leave lands sold to Jewish buyers), and he instituted an investigation to determine how many Arabs were actually landless. Chancellor could not persuade his colleagues to provide massive funding for an agricultural bank that would have enabled some of the peasants to emerge from perennial indebtedness.

A British objective to prevent Arabs from selling land to Jews failed. The Palestine Arab press and British officials continuously complained publicly and privately that Palestinian Arabs willingly, actively, and continuously sold land to Jewish buyers. Many editorials in the Palestinian Arab press claimed that their leadership looked the other way when land passed from Arabs to Jews. The application of the 1939 British White Paper on Palestine, that restricted Jewish immigration and clamped down on Jewish land purchase did slow down but did not stop the growth of a Jewish state; illegal Jewish immigration and Jewish land purchase continued until Israel was established. Likewise, Arab sales continued, with overwhelming evidence provided in 1945 The Land Transfer Inquiry Report, about the magnitude of land sales in the early 1940s when it was supposed to be prohibited.

Chancellor’s choice to impose legal restrictions on Jewish state building failed. Neither he nor other British officials could stop an economic process were buyers and sellers sought each other out vigorously and continuously. In 1940, a Colonial Office official, Sir John Shuckburgh in commenting on Zionist land purchase restrictions noted that ‘the Arab had to be protected against himself.’ Ernest Begin as Foreign Minister after World WW II wanted to stop Jewish state building as did Truman’ State Department. British paternalism to assist the Arabs or oppose and stop Zionism as a movement did not succeed in large measure because the Arab population in Palestine itself was not fully committed and engaged as individuals and as a collective in preventing the Zionism’s growth.

— Ken Stein, July 12, 2024