Peel Commission Report, Findings and Recommendations of the Royal Commission, excerpts

(July 1937)

Royal Institute of International Affairs, Great Britain and Palestine, 1915-1945, Information Paper No. 20, Oxford University Press, 1947. 155-9. See also Palestine (Peel) Partition Report. Conclusion and Recommendations 263-397. Cmd. 5479. 1937.

In 1928 and 1929, civil disturbances broke out in Palestine. Inter-communal tensions increased, as Arab political leaders and Arab peasants increasingly felt unable to direct British policy away from supporting the Jewish national home. The British government in London and those in the British administration in Palestine were greatly distressed that violence had erupted between Muslim and Jew. In an effort to look at the underlying causes of the unrest, the British government sent commissions of inquiry to Palestine (the Shaw Commission and Hope Simpson investigation) in 1929 and 1930 respectively. Each found that Jewish immigration was a cause of Arab unrest; and found that Arab action in selling land to Jews was also a cause of civilian unrest. British officials concluded that the per capita amount of available cultivable land for the Jewish and Arab populations decreased as the population of both communities increased, (Jews via immigration and Arabs mainly via improved health care). Despite these findings, British policy continued along the path of allowing the Jewish national home to grow.

Complicating Palestinian politics in the early 1930s was the severe deterioration of the agricultural economy upon which ninety percent of the Arab community depended.

While draught and poor agricultural yields plagued the Arab rural population, Jewish immigration and land purchase continued. Neither the Arab leadership in Palestine nor the British policy makers in Palestine or London did much to assist the rural Arab population. In the early 1930s, writers in Arab newspapers in Palestine and various Arab political leaders continued to protest against Zionism, demanding a cessation of Jewish immigration and land acquisition; criticism in the Palestinian Arab press was leveled at the Arab leadership for doing little than other issuing protests. Zionists were steadily bolstered by the reality that Arab sellers constantly approached Jewish buyers. For most Zionists, the dramatic inconsistency between public demands to stop the Jewish national home, and private Arab actions of aiding the Zionists through land sales maintained Zionist disbelief about a true Arab commitment to claimed nationalist ideals.

In late 1935, leaders of the Palestinian Arab community made three demands of the British High Commissioner, Arthur Wauchope:

1) the establishment of a democratic government in the country

2) immediate cessation of Jewish immigration

3) prohibition by law of the transfer of Arab land to Jews

High Commissioner Wauchope did not acquiesce to these demands, although he did indicate that some legislation would be enacted in the land sphere and that immigration would be restricted. Motivated to remain in Palestine for strategic reasons, particularly the protection of the Suez Canal, Britain was not prepared to relinquish control over Palestine to the Arab community.

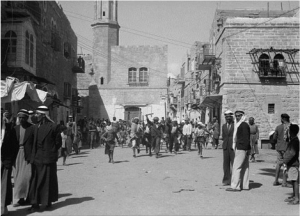

By the spring of 1936, in addition to the five previous years of poor agricultural yields, the impact of the world-wide recession on Palestinian exports, and reduced inflow of Jewish immigrant capital, Arab unemployment increased to higher than ever levels. Arabs who migrated from the central hills to the coastal plain in order to find employment in the earlier urban building boom or around Jewish areas of settlement could no longer find work. In April 1936 Arab peasants rioted against their economic state of affairs, pro-Zionist British policy, and the idea that Jews were controlling large swatches of land along the coastal plain. The disturbances evolved into a prolonged Arab general strike. Arab bands attacked Jewish settlements, uprooted crops, squatted on Jewish property, attacked British installations and personnel, and destroyed railway tracks, bridges, telegraph equipment, and army depots— all symbols of the British colonial presence. The Arab “disturbances,” or “revolt,” radicalized Arab politics, making any agreement with the Zionists highly unlikely. The revolt deepened the control of the more radical elements among the Palestinian Arab community. In particular, the position of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Amin al-Husayni; remained adamantly uncompromising to Zionism, the British, and the Jewish national home.

A lull in the disturbances came in August, a month after Britain had named a Royal Commission to ascertain their underlying causes of the unrest, to inquire into the operation of the Mandate, to evaluate legitimate Arab and Jewish grievances, and to recommend means to prevent the recurrence of such disturbances. For the Zionists, Arab violence against them reaffirmed their commitment to confront the physical challenges and engage furiously in a political and diplomatic battle to postpone any limitations on the growth of the Jewish national home.

Issued in July 1937, the 400-page Peel (Royal Commission) Report was an incisive and balanced review of the British Mandate. It gave sympathetic accountings of both Jewish and Arab aspirations. It ascertained that the underlying causes of the recent disturbances were the same as those in 1920, 1921, 1929, and 1933: the Arab desire for independence, the Arab hatred and fear of the Jewish national home and the determination of the Jewish national movement to realize its goals. It concluded that the two communities’ aspirations were irreconcilable, that the Mandate in its existing form was unworkable, and that Palestine should be partitioned into distinct Jewish and Arab entitites. The Report attached a map of the proposed Arab and Jewish states and a neutral enclave for British control of the Holy Places in Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

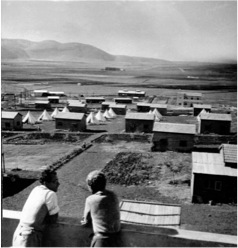

The Report said, “The Jewish National Home is no longer an experiment. The growth of its population has been accompanied by political, social and economic developments along the lines laid down at the outset. The chief novelty is the urban and industrial development. The contrast between the modern democratic and primarily European character of the National Home and that of the Arab world around it is striking. The temper of the Home is strongly nationalist. There can be no question of fusion or assimilation between Jewish and Arab cultures. The National Home cannot be half-national.”

Britain had come to the conclusion that the conflict in Palestine was not between a right and a wrong but between two rights. The use of force to settle the conflict was not an option for Britain. The British Foreign Secretary Ormsby-Gore said that there were, “Two forces operating on public opinion in England: a desire to help the suffering Jews of Europe and a considerable volume of opinion formerly represented by the Liberal Party, but now shared by all, which stood for the inherent rights of the indigenous native population.”

The Report marked the first time that partition, or the division of Palestine into two states had been proposed by an official British body. By suggesting partition, Britain admitted partial failure of its policy of trying to manage, if not reconcile the needs of the Arab and Jewish communities. Still, the Jewish national home, whose establishment had been a central part of Britain’s Mandate, had in fact been constituted. And while the Arabs had not gained independence, they had derived great moral, intellectual and material advantages from the Mandate.[2]

The Arab community in Palestine utterly rejected the notion of partition, as did neighboring Arab leaders and states: in September 1937, in Bludan, Syria, a non-governmental pan-Arab Congress of over 400 Arab delegates rejected the partition of Palestine, declaring instead its goal as “liberation of the country and establishment of an Arab government.” The Zionist response was more nuanced, neither endorsing partition nor rejecting it outright. Sandwiched in between the publication of the Peel Report and the Bludan meeting, the Twentieth Zionist Congress met in Zurich. It was forty years after the first Zionist Congress had met in Basle. Hebrew had been revived, Tel Aviv had been founded, the Hebrew University had been established, the Jewish population had grown from 24,000 to almost 400,000, Jewish land ownership had tripled, Jewish settlement on the land was a national ethos, faith in Jewish political power and organization was a reality – in other words, the territorial, economic, and financial infrastructure for a Jewish state had been put in place. Yet Zionists, while happy to hear that the British recommended partition, believed the time was not yet ripe and that the proposed Jewish state was too small. Zionist leaders involved in the deliberations over the partition debate did not sense that European Jews were facing an immediate danger radically different from those which Jews had lived with throughout history, so the immediate need for a Jewish national home did not, at the time, seem more pressing than in years past.3 Zionist leaders wanted to further strengthen the Jewish national home in preparation for the state on the way.

After the issuance of the Peel Report, not completely certain that leaving Palestine was at the moment the strategic choice, given unfolding events in Europe and Britain’s need for the oil refinery port at Haifa, Britain sent a technical commission to Palestine to look into possible boundaries for the two-state solution. In October 1938, the Partition (Woodhead) Commission concluded that dividing Palestine was impossible. When partition was ruled impracticable, Britain invited Zionists, Arab state leaders, and Palestinians to London in early 1939 to confer about future policy. The combined effects of the 1936-39 Arab disturbances against Britain and Zionism and the issuance of the Peel and Partition Commission Reports gave London policy- makers a cover to restructure the Mandate’s operation. Gathering war clouds in Europe and concern for maintaining reasonable relations with Arab leaders meant ending the unrest in Palestine by truncating the Jewish national home. That directive came via the May 1939 White Paper that severely limited Jewish immigration and land purchase.

The 1937 partition proposal had long-term ramifications for the Arab-Jewish conflict in Palestine. Even before the Peel report was issued, the notion of partition was in Palestine’s political air; the Zionists and the Arabs understood the implications. There is no doubt that the Arabs in Palestine knew that Zionism was already a success. British officials in London and the Middle East made the case that it was more important to mollify Middle Eastern Arab leaders’ interests than it was to worry about the growth of the Jewish national home. The idea of partition was eventually withdrawn, because it was felt certain to alienate positive Arab sentiment toward Britain.5 The partition option would continue to be evaluated by British policy makers during the war years, without any definitive conclusion being reached.

-Ken Stein, November 2011

A. The Underlying Causes

…This seems to us to be an appropriate point to deal with the first of our terms of reference, which requires us “to ascertain the underlying causes of the disturbances…

B. Recommendations under the Mandate Administration

There should be no hesitation in dispensing with the services of Palestinian officers whose loyalty or impartiality is uncertain.

There should be more decentralization.

A British Senior Government Advocate should be appointed.

The Jaffa-Haifa road should be completed as speedily as possible.

Public Safety. Should disorders break out again of such a nature as to require the intervention of the military, there should be no hesitation in enforcing martial law. In such an event, the disarmament first of the Arabs and then of the Jews should be enforced.

In mixed areas, British District Officers should be appointed.

Central and local police reserves are necessary. A large mobile mounted force is also essential.

A more rigorous Press Ordinance should be adopted.

Financial and Fiscal Questions. Negotiations should be opened to amend the provisions of Article 18 of the Mandate and put the trade of Palestine on a fairer basis.

Land. The High Commissioner should be empowered to prohibit the transfer of land in any stated area to Jews. (The amendment of the Mandate may first be necessary.)

Until survey and settlement are complete, the sale of isolated and comparatively small plots of land to Jews should be prohibited. The Commission favors a proposal for the creation of special Public Utility Companies to undertake development schemes.

An expert Committee should be appointed to draw up a Land Code.

Settlement should be expedited.

In the event of further sales of land by Arabs to Jews, the rights of any Arab tenants or cultivators must be preserved. Alienation of land should only be allowed where it is possible to replace extensive by intensive cultivation, i.e. in the plains, and not at present in the hills.

Legislation vesting surface water in the High Commission is essential. Possibilities of irrigation should be explored. The scheme for the development of the Huleh district is commended.

Measures of afforestation are recommended.

Immigration. The volume of Jewish immigration should continue to be restricted in the first instance by the economic absorptive capacity of Palestine, but it should be subject to a “political high level,” covering Jewish immigration of all categories. This high level should be fixed for the next five years at 12,000 per annum. Amendments in the categories under the Immigration Ordinance and in the definition of “dependency” are proposed.

Education. The Administration should regard the claims on the revenue of Arab education as second in importance only to those of public security. The present proportion between the grant to Jewish education and the amount spent on the Arabs should not be altered: an increase in the grant to the Jews should result from an increase in the total expenditure on education.

In any further discussion of the project of a British University in the Near East, the possibility should be considered of locating it in the neighborhood of Jerusalem or Haifa.

Local Government. An attempt should be made to strengthen those few local councils which still exist in Arab rural areas, but not to revivify councils which have been broken down, or to create new ones unless there is a genuine demand for them. The more important local councils and all the municipalities should be reclassified, by means of a new Ordinance, into groups according to their respective size and importance.

The services of an expert on local government should be obtained to assist in drafting the new Ordinance and improving the relations between the Government and the municipalities.

The need of Tel Aviv for a substantial loan should be promptly and sympathetically reconsidered.

Self-Governing Institutions. The Commission does not recommend that any attempt be made to revive the proposal of a Legislative Council, but they would welcome an enlargement of the Advisory Council by the addition of Unofficial Members.

Conclusion. The above recommendations for dealing with Arab and Jewish grievances under the Mandate will not “remove” them or “prevent their recurrence.” They are the best palliatives the Commission can devise, but they will not solve the problem.

C. Recommendations for Termination of the Mandate on a Basis of Partition

Having reached the conclusion that there is no possibility of solving the Palestine problem under the existing Mandate (or even under a scheme of cantonization), the Commission recommends the termination of the present Mandate on the basis of Partition and put forward a definite scheme which they consider to be practicable, honorable, and just. The scheme is as follows:

The Mandate for Palestine should terminate and be replaced by a Treaty System in accordance with the precedent set in Iraq and Syria.

Under Treaties to be negotiated by the Mandatory with the Government of Transjordan and representatives of the Arabs of Palestine on the one hand, and with the Zionist Organization on the other, it would be declared that two sovereign independent States would shortly be established:

- An Arab State consisting of Transjordan united with that part of Palestine allotted to the Arabs; and

- A Jewish State consisting of that part of Palestine allotted to the Jews.

The Mandatory would undertake to support any requests for admission to the League of Nations made by the Governments for the Arab and Jewish States. The Treaties would include strict guarantees for the protection of minorities. Military Conventions would be attached to the Treaties.

A new Mandate should be instituted to execute the trust of maintaining the sanctity of Jerusalem and Bethlehem and ensuring free and safe access to them for all the world. An enclave should be demarcated to which this Mandate should apply, extending from a point north of Jerusalem to a point south of Bethlehem, and access to the sea should be provided by a corridor extending from Jerusalem to Jaffa. The policy of the Balfour Declaration would not apply to the Mandated Area.

The Mandatory should also be entrusted with the administration of Nazareth and with full powers to safeguard the sanctity of the waters and shores of Lake Tiberias, and similarly with the protection of religious endowments and of such buildings, monuments and places in the Arab and Jewish States as are sacred to the Jews and the Arabs respectively.

The frontier between the Arab and Jewish States recommended is as follows: Starting from Ras an Naqura, it follows the existing northern and eastern frontier of Palestine to Lake Tiberias and crosses the Lake to the outflow of the River Jordan, whence it continues down the river to a point rather north of Beisan. It then cuts across the Beisan Plain and runs along the southern edge of the Valley of Jezreel to a point near Megiddo, whence it crosses the Carmel Ridge in the neighborhood of the Megiddo Road. It then runs southward down the eastern edge of the Maritime Plain, curving west to avoid Tulkarm, until it reaches the Jerusalem-Jaffa Corridor near Lydda. South of the Corridor, it continues down the edge of the Plain to a point about ten miles south of Rehovot, whence it turns west to the sea.

Haifa, Tiberias, Safad, and Acre should be kept for a period under Mandatory administration. Jaffa should form an outlying part of the Arab State, narrow belts of land being acquired and cleared on the north and south sides of the town to provide access from the Mandatory Corridor to the sea.

The Jewish Treaty should provide for free transit of goods in bond between the Arab State and Haifa.

In view of possible commercial developments in the future, an enclave on the north-west coast of the Gulf of Aqaba should be retained under Mandatory administration, and the Arab Treaty should provide for free transit of goods between the Jewish State and this enclave, as also to the Egyptian frontier at Rafah. The Treaty should provide for similar facilities for the transit of goods between the Mandated Area and Haifa, Rafah, and the Gulf of Aqaba.

The Jewish State should pay a subvention to the Arab State. A Finance Commission should be appointed to advise as to its amount and as to the division of the public debt of Palestine and other financial questions.

In view of the backwardness of Transjordan, Parliament should be asked to make a grant of ₤2,000,000 to the Arab State.

As a part of the proposed Treaty System, a Commercial Convention should be concluded with a view to establishing a common tariff over the widest possible range of imported articles and to facilitating the freest possible interchange of goods between the three territories.

The rights of all existing Civil Servants, including rights to pensions or gratuities, should be fully honored.

Agreements entered into by the Government of Palestine for the development and security of industries, e.g. that with the Palestine Potash Company, should be taken over and carried out by the Governments of the Arab and Jewish States. Guarantees to that effect should be given in the Treaties. The security of the power station at Jisr el Majami should be similarly guaranteed.

The Treaties should provide that if Arab owners of land in the Jewish State or Jewish owners in the Arab State wish to sell their land, the Government of the State concerned should be responsible for purchases at a price to be fixed, if required, by the Mandatory Government.

An immediate inquiry should be undertaken into the possibilities of irrigation and development in Transjordan, the Beersheba District, and the Jordan Valley. If it becomes clear that a substantial amount of land could be made available for the resettlement of Arabs living in the Jewish Area, strenuous efforts should be made to obtain an agreement, in the interests of both parties concerned, for an exchange of land and population. To facilitate such an agreement, the United Kingdom Parliament should be asked to make a grant to meet the cost of the necessary development scheme.

For the transition period which would intervene before the Treaties came into force, the Commission’s recommendations are as follows: Land purchase by Jews within the Arab Area or by Arabs within the Jewish Area should be prohibited. No Jewish immigration into the Arab Area should be permitted. The volume of Jewish immigration should be determined by the economic absorptive capacity of Palestine less the Arab Area. Negotiations should be opened without delay to secure amendment of Article 18 of the Mandate and place the external trade of Palestine on a fairer basis. The Advisory Council should, if possible, be enlarged by the nomination of Arab and Jewish representatives. The municipal system should be reformed on expert advise, as recommended. A vigorous effort should be made to increase the number of Arab schools.

The Commission points out that, while these proposals do not offer either the Arabs or the Jews all they want, they offer each party what it wants most, namely, freedom and security…

D. Conclusion

1. “Half a loaf is better than no bread” is a peculiarly English proverb; and, considering the attitude which both the Arab and Jewish representatives adopted in giving evidence before us, we think it improbable that either party will be satisfied at first sight with the proposals we have submitted for the adjustment of their rival claims. For Partition means that neither will get what it wants. It means that the Arabs must acquiesce in the exclusion from their sovereignty of a piece of territory, long occupied and once ruled by them. It means that the Jews must be content with less than the Land of Israel they once ruled and have hoped to rule again. But it seems to us possible that on reflection, both parties will come to realize that the drawbacks of Partition are outweighed by its advantages. For, if it offers neither party all it wants, it offers each what it wants most, namely, freedom and security.

2. The advantages to the Arabs of Partition on the lines we have proposed may be summarized as follows:

a. They obtain their national independence and can cooperate on an equal footing with the Arabs of the neighboring countries in the cause of Arab unity and progress.

b. They are finally delivered from the fear of being “swamped” by the Jews and from the possibility of ultimate subjection to Jewish rule.

c. In particular, the final limitation of the Jewish National Home within a fixed frontier and the enactment of a new Mandate for the protection of the Holy Places solemnly guaranteed by the League of Nations removes all anxiety lest the Holy Places should ever come under Jewish control.

d. As a set-off to the loss of territory the Arabs regard as theirs, the Arab State will receive a subvention from the Jewish State. It will also, in view of the backwardness of Transjordan, obtain a grant of ₤2,000,000 from the British Treasury and, if an arrangement can be made for the exchange of land and population, a further grant will be made for the conversion, as far as may prove possible, of uncultivable land in the Arab State into productive land from which the cultivators and the State alike will profit.

3. The advantages of Partition to the Jews may be summarized as follow:

a. Partition secures the establishment of the Jewish National Home and relieves it from the possibility of its being subjected in the future to Arab rule.

b. Partition enables the Jews in the fullest sense to call their National Home their own: for it converts it into a Jewish State. Its citizens will be able to admit as many Jews into it as they themselves believe can be absorbed. They will attain the primary objective of Zionism – a Jewish nation, planted in Palestine, giving its nationals the same status in the world as other nations give theirs. They will cease at last to live a “minority life.”

4. To both Arabs and Jews, Partition offers a prospect – and we see no such prospect in any other policy – of obtaining the inestimable boon of peace. It is surely worth some sacrifice on both sides if the quarrel which the Mandate started could be ended with its termination. It is not a natural or old-standing feud. An able Arab exponent of the Arab case told us that the Arabs throughout their history have not only been free from anti-Jewish sentiment but have also shown that the spirit of compromise is deeply rooted in their life. And he went on to express his sympathy with the fate of the Jews in Europe. “There is no decent-minded person,” he said, “who would not want to do everything humanly possible to relieve the distress of those persons,” provided that it was “not at the cost of inflicting a corresponding distress on another people.” Considering what the possibility of finding a refuge in Palestine means to many thousands of suffering Jews, we cannot believe that the “distress” occasioned by Partition, great as it would be, is more than Arab generosity can bear. And in this, as in so much else connected with Palestine, it is not only the peoples of that country that have to be considered. The Jewish problem is not the least of the many problems which are disturbing international relations at this critical time and obstructing the path to peace and prosperity. If the Arabs, at some sacrifice, could help to solve that problem; they would earn the gratitude, not of the Jews alone, but of all the Western World.

5. There was a time when Arab statesmen were willing to concede little Palestine to the Jews, provided that the rest of Arab Asia were free. That condition was not fulfilled then, but it is on the eve of fulfillment now. In less than three years’ time, all the wide Arab area outside Palestine between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean will be independent, and, if Partition is adopted, the greater part of Palestine will be independent too.

6. There is no need to stress the advantage to the British people of a settlement in Palestine. We are bound to honor to the utmost of our power the obligations we undertook in the exigencies of war towards the Arabs and the Jews. When those obligations were incorporated in the Mandate, we did not fully realize the difficulties of the task it laid on us. We have tried to overcome them, not always with success. They have steadily become greater till now they seem almost insuperable. Partition offers a possibility of finding a way through them, a possibility of obtaining a final solution of the problem which does justice to the rights and aspirations of both the Arabs and the Jews and discharged the obligations we undertook towards them twenty years ago to the fullest extent that is practicable in the circumstances of the present time…

UNISPAL.NSF/85255e950050831085255e95004fa9c3/fd05535118aef0de052565ed0065ddf7

[3]Shapira, Anita. “The Concept of Time in the Partition Controversy of 1937,” Studies in Zionism, Vol 6, No. 2 (Autumn 1985), p. 228. [4] Great Britain. Palestine Partition Commission Report, Cmd. 5854 (1938).