May 8, 2014

http://www.state.gov/p/nea/rls/rm/225840.htm

Printable PDFLast July, President Obama and Secretary of State John Kerry launched a vigorous effort to reach a final status agreement between Israelis and Palestinians. Now it is early May, we have passed the nine-month marker for these negotiations, and for the time being the talks have been suspended. Some have said this process is over. But that is not correct. As my little story testifies. As you all know well— in the Middle East, it’s never over.

Think back to the spring of 1975, the year the United States brokered the Sinai II agreement. In March of that year, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger set out to the region to broker a second disengagement agreement between Israel and Egypt. After ten days of shuttling back and forth between the parties, the Secretary of State suspended his efforts and returned to Washington empty handed. The President, President Ford, and the Secretary announced they would step back. Kissinger vented his frustration. Maybe a David Ben-Gurion or a Golda Meir could lead Israel to a peace agreement, he fumed, but never a Yitzhak Rabin! We learned a little later what a peacemaker Yitzhak Rabin could be.

Everybody thought it was over. Of course, as we know now, everybody was wrong. A few months later the talks were restarted, and soon thereafter a deal was reached.

What was true then is possibly true today: this process is always difficult, but it is never impossible.

But in certain ways, things were more difficult in the Kissinger days and in some ways, they were easier. For an audience that loves Middle East history, I think it is interesting to take stock of what has changed and what has stayed the same since Henry’s time.

In some ways things are easier in the Israeli-Palestinian context today than in the past.

The international context for peacemaking is better today. The Cold War and fear that a conflict in the Middle East would trigger a nuclear superpower confrontation is no longer there.

The region has not faced an all-out Arab-Israeli war in 40 years. Peace treaties with Egypt and Jordan have held today despite very difficult circumstances—two intifadas, conflicts with Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza, and of course the Arab Revolutions. Turmoil in the Mideast is bringing Israelis and Arab states closer together. Indeed, there is a virtual realignment taking place between the enemies of moderation on the one side and the proponents of moderation on the other that crossed the Arab Israeli divide. As Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu has noted, “many Arab leaders today already realize that Israel is not their enemy, that peace with the Palestinians would turn our relations with them and with many Arab countries into open and thriving relationships.”

In the Israeli-Palestinian domestic arena there is, in some ways, greater political realism than before. Back in Kissinger’s day, Golda Meir said there was no such thing as a Palestinian people. Now a Likud prime minister says there has to be two states for two people. Back then, Yasser Arafat was committed to Israel’s destruction. Today, his successor, Abu Mazen, is committed to living alongside Israel in peace.

The U.S.-Israel relationship has also changed in quite dramatic ways. Only those who know it from the inside – as I have had the privilege to do – can testify to how deep and strong are the ties that now bind our two nations. When President Obama speaks with justifiable pride about those bonds as “unbreakable” he means what he says. And he knows of what he speaks. Unlike the “reassessment” Kissinger did in the Ford Administration, there is one significant difference: President Obama and Secretary Kerry would never suspend U.S.-Israel military relations as their predecessors did back then. Those military relations are too important to both our nations.

However, in many respects, when it comes to peace negotiations, things have proven to be much harder today than in the 1970s.

Kissinger faced Israelis and Egyptians who were coming off the painful 1973 war. I was an Australian student in Israel at the time. I remember well the sense of existential dread in the country brought on by the scope of Israeli casualties, and I remember also a willingness to consider withdrawals from Sinai that had previously been ruled out. Few of you remember Moshe Dayan stated before the 1973 war that he would rather have Sharm el Sheikh than peace. Egypt also had a sense of urgency, generated by Sadat’s belief that only peace with Israel could change Egypt’s dire circumstances and only U.S. diplomacy could achieve that peace.

Yet, where is this sense of urgency today? To be absolutely clear, I am not for a moment suggesting that violence is necessary to produce urgency and flexibility. That is abhorrent. We are very fortunate to have two leaders, in President Abbas and Prime Minister Netanyahu, who are committed to achieving a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through peaceful means.

But one problem that revealed itself in these past nine months is that the parties, although both showing flexibility in the negotiations, do not feel the pressing need to make the gut-wrenching compromises necessary to achieve peace. It is easier for the Palestinians to sign conventions and appeal to international bodies in their supposed pursuit of “justice” and their “rights,” a process which by definition requires no compromise. It is easier for Israeli politicians to avoid tension in the governing coalition and for the Israeli people to maintain the current comfortable status quo. It is safe to say that if we the US are the only party that has a sense of urgency, these negotiations will not succeed.

Kissinger also had the advantage of being able to pursue peace incrementally – what he labeled the “step-by-step” approach. He told me recently that he introduced that idea because, after the trauma of the Yom Kippur War, he believed Israeli society could not handle the big jump to a total withdrawal from Sinai. It took six years from war to peace on the Israeli-Egyptian front. On the Israeli-Palestinian front, the Oslo Accords provided for an interim process that was supposed to last five years. It has now been twenty years since Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat shook hands on the White House south lawn. Since then, thousands of Israelis and Palestinians have died and the interim process is now thoroughly stuck, with further redeployments and road maps turned into road kill along the way.

An interim period that was designed to build trust has in fact exacerbated mistrust: suicide bombings, the second intifada, and continuous settlement growth have led many people on both sides to lose faith. This is why Secretary Kerry, with the full backing of President Obama, decided to try this time around for a conflict-ending agreement.

There are other differences too. Egypt is a state with a five thousand year history, capable of living up to its commitments. The Palestinians are just now in the process of building their state and given the bitter experience of the second intifada and the consequences of the unilateral withdrawal from Gaza, Israelis don’t trust them to live up to any of their commitments. Even now, after a serious U.S.-led endeavor to build credible Palestinian security services, after seven years of security cooperation that the IDF and the Shin Bet now highly appreciate, and Abu Mazen’s efforts to promote non-violence in the face of pressure from extremists, the fundamental mistrust remains.

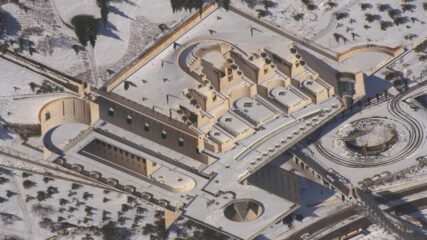

The geographic context is different too. The Sinai Peninsula is a 200 kilometer buffer zone between Israel and Egypt. Israelis and Palestinians live virtually on top of each other. Moreover, the geographic issues are at the heart of what it means to be a Palestinian or an Israeli. The core issues – land, refugees, Jerusalem – have defined both peoples for a very long time. It is part of their identity in a way that the Sinai desert was not.

Now, as back in 1975, we face a breakdown in talks, with both sides trying to put the blame on the other party. The fact is both the Israelis and Palestinians missed opportunities, and took steps that undermined the process. We have spoken publicly about unhelpful Israeli steps that combined to undermine the negotiations. But it is important to be clear: We view steps the Palestinians took during the negotiations as unhelpful too. Signing accession letters to fifteen international treaties at the very moment when we were attempting to secure the release of the fourth tranche of prisoners was particularly counterproductive. And the final step that led to the suspension of the negotiations at the end of April was the announcement of a Fatah-Hamas reconciliation agreement while we were working intensively on an effort to extend the negotiations.

But it is much more important to focus on where we go from here. And it is critical that both sides now refrain from taking any steps that could lead to an escalation and dangerous spiral that could easily get out of control. Thus far since the negotiations been suspended they have both shown restraint and it is essential that this continue.

We have also spoken about the impact of settlement activity. Just during the past nine months of negotiations, tenders for building 4,800 units were announced and planning was advanced for another 8,000 units. It’s true that most of the tendered units are slated to be built in areas that even Palestinian maps in the past have indicated would be part of Israel. Yet the planning units were largely outside that area in the West Bank. And from the Palestinian experience, there is no distinction between planning and building. Indeed, according to the Israeli Bureau of Census and Statistics, from 2012 to 2013 construction starts in West Bank settlements more than doubled. That’s why Secretary Kerry believes it is essential to delineate the borders and establish the security arrangements in parallel with all the other permanent status issues. In that way, once a border is agreed each party would be free to build in its own state.

I also worry about a more subtle threat to the character of the Jewish state. Prime Minister Netanyahu himself has made clear, the fundamental purpose of these negotiations is to ensure that Israel remains a Jewish and democratic state − not a de facto bi-national state. The settlement movement on the other hand may well drive Israel into an irreversible binational reality. If you care about Israel’s future, as I know so many of you do and as I do, you should understand that rampant settlement activity – especially in the midst of negotiations – doesn’t just undermine Palestinian trust in the purpose of the negotiations; it can undermine Israel’s Jewish future. If this continues, it could mortally wound the idea of Israel as a Jewish state – and that would be a tragedy of historic proportions.

Public opinion was another element that we found very challenging over the past 9 months. Kissinger focused very little on this element, because while the Israelis and Egyptians fought wars with each other, their societies were not physically intertwined. The peace between two states mediated by Dr. Kissinger was not psychologically difficult. Israelis and Palestinians by contrast are both physically intertwined and psychologically separated and terrorism and occupation have added to the trauma between the peoples, making everything harder.

Consistently over the last decade polling on both sides reveals majority support for the two state solution. But as many of you know neither side believes the other side wants it and neither seems to understand the concerns of the other. For example, Palestinians don’t comprehend the negative impact of their incitement on the attitudes of Israelis. When Palestinians who murdered Israeli women and children are greeted as “heroes” in celebration of their release, who can blame the Israeli public – parents who lost children, and children who lost parents – for feeling despair. On the other side, Palestinians feel that Israelis don’t even see their suffering any more, thanks to the success of the security barrier and the security cooperation. One Palestinian negotiator told his Israeli counterparts in one of our sessions: “You just don’t see us; we are like ghosts to you.”

Israelis don’t seem to appreciate the highly negative impact on the Palestinian public of the IDF’s demolition of Palestinian homes, or military operations in populated Palestinians towns that are supposed to be the sole security responsibility of the Palestinian Authority, or the perceived double standard applied to settlers involved in “price tag” attacks. Palestinians cannot imagine how offended and suspicious Israelis become when they call Jews only a religion and not a people. Israelis cannot understand why it took a Palestinian leader 65 years to acknowledge the enormity of the Holocaust; Palestinians cannot understand why their leader should have been denigrated rather than applauded for now doing so. And the list goes on and on.

The upshot of these competing narratives, grievances and insensitivities is that they badly affected the environment for negotiations. While serious efforts were under way behind closed doors, we tried to get the leaders and their spokesmen to engage in synchronized positive messaging to their publics. Instead, Prime Minister Netanyahu was understandably infuriated by the outrageous claims of Saeb Erekat, the Palestinian chief negotiator no less, that the Prime Minister was plotting the assassination of the Palestinian president. And Abu Mazen was humiliated by false Israeli claims that he had agreed to increased settlement activity in return for the release of prisoners.

So, why then in the face of all of this, do I believe that direct negotiations can still deliver peace? Because over the last nine months, behind the closed doors of the negotiating rooms, I’ve witnessed Israelis and Palestinians engaging in serious and intensive negotiations. I’ve seen Prime Minister Netanyahu straining against his deeply-held beliefs to find ways to meet Palestinian requirements. I’ve seen Abu Mazen ready to put his state’s security in American hands to overcome Israeli distrust of Palestinian intentions. I have seen moments where both sides have been unwilling to walk in each other’s shoes. But I have also witnessed moments of recognition by both sides of what is necessary. I have seen moments when both sides talked past each other without being able to recognize it. But I have also seen moments of genuine camaraderie and engagement in the negotiating room to find a settlement to these vexing challenges.

The reality is that aside from Camp David and Annapolis, serious permanent status talks have been a rarity since the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. For all of its flaws, this makes the past nine months important. In twenty rounds over the first six months, we managed to define clearly the gaps that separate the parties on all the core issues. And since then we have conducted intensive negotiations with the leaders and their teams to try to bridge those gaps. Under the leadership of General Allen, we have done unprecedented work to determine how best to meet Israel’s security requirements in the context of a two state solution — which Secretary Kerry has emphasized from Day One is absolutely essential to any meaningful resolution to this conflict. As a result we are all now better informed about what it will take to achieve a permanent status agreement.

One thing that will never change and is as true today as it was during Kissinger’s time is that peace is always worth pursuing, no matter how difficult the path. Indeed, until the very last minute it may seem impossible, as it did in Kissinger’s day. The cynics and critics will sit on the sidelines and jeer. They will say I told you so. They are doing it already. They will even claim that the United States is disengaging from the world, even as we have been deeply engaged in this issue that matters so much to so many of our partners around the globe. But we will make no apologies for pursuing the goal of peace. Secretary Kerry certainly won’t. And President Obama won’t. To quote Secretary Kerry “the United States has a responsibility to lead, not to find the pessimism and negativity that’s so easily prevalent in the world today.”

And the benefits are just too important to let go. For Palestinians: A sovereign state of their own. A dignified future. A just solution for the refugees. For Israelis: A more secure Jewish and democratic homeland. An opportunity to tap into the potential for a strategic alliance and deep economic relations with its Arab neighbors. For all of us. For all of the children of Abraham. An opportunity for a more prosperous, peaceful, and secure future.

Whether we get there or not, however, ultimately comes down to leadership. After a five months pause, Kissinger was able to resume the negotiations with Rabin and Sadat and bring them to a successful Sinai II Disengagement Agreement because Rabin was eventually capable of overcoming his political constraints and Sadat was prepared to make positive gestures that made it possible for Rabin to do so. As Dr. Kissinger has noted, “The task of the leader is to get his people from where they are to where they have not been before.”

Let’s hope it won’t take a five month pause this time. Let’s hope that President Abbas and Prime Minister Netanyahu are able to overcome the hurdles that now lie on that path back to the negotiating table. When they are ready, they will certainly find in Secretary Kerry and President Obama willing partners in the effort to try again – if they are prepared to do so in a serious way. The obvious truth is that neither Israelis nor Palestinians are going away. They must find a way to live together in peace, respecting each other, side-by-side, in two independent states. There is no other solution. The United States stands ready to assist in this task, to help the leaders take their peoples to where they have never been, but where they still dream of going.

Thank you very much.