Udi Dekel, Anat Kurz and Noa Shusterman, INSS, February 24, 2020

With permission, read full article at INSS.

Special Publication, February 24, 2020

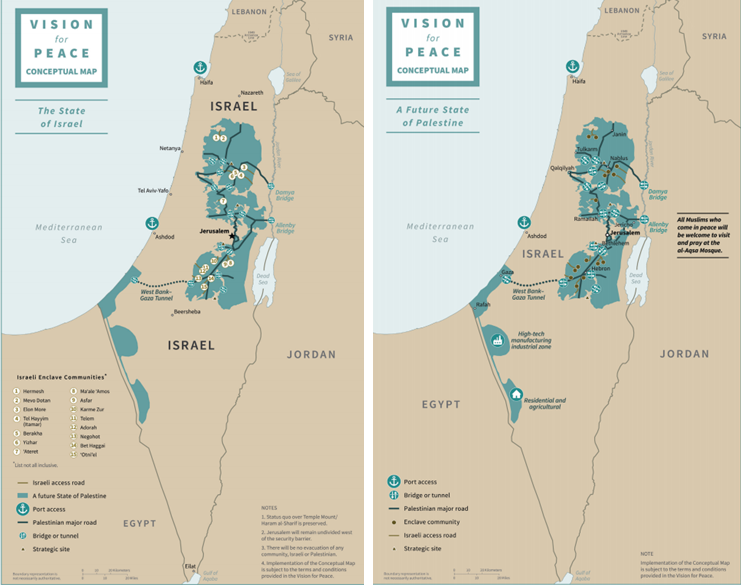

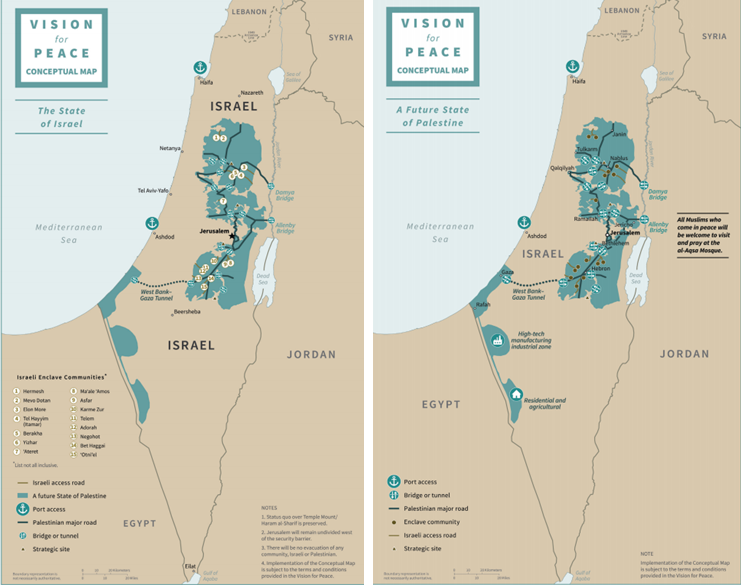

“The Deal of the Century,” formulated by the Trump administration, is presented as a new paradigm for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that also shapes the architecture of a new Middle East. The plan recognizes Israel’s extensive security requirements and enables Israel to apply its sovereignty on the settlement blocs, the Jordan Valley, and the isolated settlements; avoids uprooting and evacuating Jewish settlers; and preserves a united Jerusalem under Israeli sovereignty. For the Palestinian side, the plan outlines the terms for establishing a non-contiguous state divided into six cantons that will be entirely enclosed by Israel, with full Israeli control of the surrounding territory and the border crossings. In addition, the plan denies a “right of return” of Palestinian refugees to Israeli territory. For the Palestinians, the practical meaning of the plan is tantamount to surrender, and they have therefore rejected it outright.

The disclosure that representatives of the Prime Minister of Israel helped formulate the plan raises several questions, including: in which Israeli government forum was the decision taken that the annexation of isolated settlements deep in Palestinian territory is more important than retaining areas in the Negev, which represent strategic depth for Israel, and in the Triangle region, in the heart of Israel? In which forum was there a discussion of the complex, weighty, and very expensive significance of the need to secure isolated settlements and a border of about 1,400 kilometers, while adding some 450,000 Palestinians within the boundaries of Israel?

Some in Israel tend to see the Trump plan and the Palestinian rejection as an opportunity for extensive moves toward annexation in the West Bank. However, when looking at the long term, annexation represents numerous risks from all dimensions – security, economy, civil society, international and regional standing – as well as the actual danger of accelerating the slide into a one-state reality. In order to keep the State of Israel Jewish, democratic, secure, and moral, it is necessary to adopt the components of the plan that both enhance security and at the same time can jumpstart the process of separation from the Palestinians, thus creating a better strategic reality for Israel.

“The Deal of the Century,” formulated by the Trump administration, is presented as a new paradigm for a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that also shapes the architecture of a new Middle East, on the basis of on an Arab-American-Israeli coalition. The plan lends different significance to principles that have guided the negotiations for a permanent status agreement between Israel and the Palestinians over the last three decades, essentially emptying them of any content. Inter alia, it rejects the Palestinian demand for “all or nothing,” in particular, the Palestinians’ ability to veto any arrangement that does not provide a complete response to their goals or deviates from the borders of June 4, 1967. However, the chances of implementing the Trump plan range between slim and nil.

At the declarative level, the plan honors Palestinian national aspirations and outlines a vision of a sustainable Palestinian state. At the same time, it emphasizes Israel’s security and the need to prevent the West Bank from becoming a kind of second Gaza Strip. However, there is a considerable gap between the vision and the conditions for implementation. For example, the conditions for recognition of the Palestinian state require Palestinian recognition of the Jewish state, i.e., an agreed arrangement between two nation states – Israel as the national home of the Jewish people and Palestine as the national home of the Palestinian people. This includes canceling the “right of return” to Israel of Palestinian refugees from 1948. Other material demands are the establishment of a functioning, democratic Palestinian regime that respects human rights at higher standards than in any other Arab state; acceptance of Israel’s security requirements; disarmament of Hamas and other terror organizations; restored control of the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian Authority, although the latter will have no military capabilities; and the cessation of Palestinian incitement against Israel in the political, public, and education systems. Clearly, it will be extremely difficult for the Palestinians to accept and implement this set of conditions.

The Practical Manifestation of the Plan’s Principles

The two state solution: Contrary to previous declarations by the plan’s authors, Jared Kushner and Jason Greenblatt, which avoided specifying a two-state objective, the plan includes the establishment of a Palestinian state with limited sovereignty over areas of the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and two enclaves in the western Negev.

Consideration of the reality created on the ground over the last five decades: Settlement blocs west of the existing security barrier, with 345,000 settlers, will be annexed to Israel. No residents of Jewish settlements east of the barrier, home to some 100,000 Jews, will be uprooted or evacuated (including 15 isolated enclaves with about 14,000 people); Israeli law will apply in full to all settlements. Palestinian enclaves of about 140,000 people will remain on Israeli territory, and their residents will have to cross Israeli territory in order to move around the West Bank.

Territory of the Palestinian state: In addition to Areas A and B, which are under Palestinian Authority rule, and the Gaza Strip, which is under Hamas control, the Palestinian state will include about half of Area C, which constitutes 60 percent of the West Bank. The remaining 30 percent of the West Bank, to be allocated to Israel, comprises the Jordan Valley (17 percent); Jewish settlement areas (3 percent); and Jewish settlement blocs and traffic routes (10 percent). In exchange, Israel will transfer two areas in the Negev (currently under Israeli sovereignty) to the Palestinian state, which will expand the Gaza Strip area (the rationale is largely humanitarian: to reduce population density in the Strip), and territory south of the Mount Hebron regional council. In addition, Israel will have the option to transfer populated areas under its sovereignty – villages and towns in the Triangle, inhabited by some 250,000 Arab citizens of Israel. There will also be traffic contiguity – roads, interchanges, and tunnels – connecting the respective Palestinian areas and the respective Israeli areas, to allow freedom of movement for people and goods and economic vitality.

Land swaps at a ratio of 2:1 in Israel’s favor: In return for the 30 percent of the West Bank area to be annexed by Israel, territory within Israel equal to about 15 percent of the West Bank (which must be approved by a referendum/with the support of 80 Knesset members) will be transferred to Palestinian control.

Israeli control of strategic routes, including Highway 1 from Jerusalem to the northern Dead Sea; Route 505, the trans-Samaria highway from Ariel to the Jordan Valley; Route 90 along the Jordan Valley; Route 80 along the hills that overlook the Jordan Valley; Highway 443 from Modiin to Jerusalem.

Two capitals in the Jerusalem area: The Palestinian capital (al-Quds, or any other name to be chosen) will include the neighborhoods outside the security barrier, including Abu Dis. This means the complete separation of the Palestinian state from East Jerusalem, and above all from the Old City, Haram a-Sharif (al-Aqsa) and Sheikh Jarrah.

Status quo of the holy sites in Jerusalem: Freedom of access and worship will be assured for all religions but Israel will have sole control of Jerusalem. (The plan recognizes Israel for having protected the holy sites over the years and ensured freedom of worship at the various sites.)

Israel’s overriding security responsibility in the air, at sea, and on land in the entire area west of the Jordan River. Thus, the Jordan Valley will be under Israeli sovereignty and serve as Israel’s eastern security border (based on sovereignty and not only security arrangements). This means Israeli control around the external perimeter of the future Palestinian state, enclosing it.

Solution to the problem of the Palestinian refugees will occur in the Palestinian state, or on the basis of rehabilitation in their places of residence or in a third country, with no “right of return” to Israel. The right of refugees to immigrate to Palestine will be determined with Israel’s agreement, limited to its security considerations. A compensation mechanism will be instituted, but Israel will not be accountable for this compensation, as it invested in the absorption and rehabilitation of Jewish refugees who fled from Arab countries after the establishment of the state.

Significance of the map: A non-contiguous Palestinian state, divided into six cantons and completely surrounded by Israeli territory; Israeli control of all the routes connecting the Palestinian territories; and Israeli security control and sovereignty of the perimeter, including external crossings (the Allenby Bridge crossing to Jordan and the Rafiah crossing to Egypt). There will be an international border of nearly 1,400 km between Israel and Palestine (almost double the length of the existing security barrier, which under the plan will be moved to the new line). The practical significance of this outline for the Palestinians is tantamount to surrender.

Jerusalem, Security, and Economics

Jerusalem

Under the plan, the core of the city of Jerusalem will remain united so that the neighborhoods within the security barrier, including the Old City, Temple Mount, the Mount of Olives, and the City of David will be included in the capital of Israel. The Palestinian capital will include the village of Abu Dis and Palestinian neighborhoods beyond the security barrier.

The plan stresses the importance of Jerusalem to the three religions, freedom of access to holy sites and freedom of worship, and Israel’s commitment to maintain the status quo in the city. The Temple Mount will be open to prayer for all religions (including Jews, which in practice means a change of the status quo). However, there is noticeable failure to mention Jordan’s special status in the holy places (Holy Custodian). Accordingly, the Palestinian Authority will be completely separated from Jerusalem, and there is no mention of Palestinian institutions and sites in the city.

Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem who remain within Israel’s borders, about 300,000 people, will be able to choose from three options: 1) Israeli residency without citizenship; 2) Palestinian citizenship; 3) Israeli citizenship. Palestinians with a blue ID card (Israeli residents) who live in neighborhoods outside the security obstacle that are designated for the Palestinian capital, including Kafr Akab and the Shuafat refugee camp, will likely move into Jerusalem to retain their current benefits.

Security

The plan meets most of Israel’s security demands, which are presented as conditions for the arrangement, and takes into account the lessons of the disengagement from the Gaza Strip. The goal is to prevent the emergence in the West Bank of a similar security situation. While these arrangements recognize Israel’s demands that were raised in previous rounds of talks, it is unlikely that the Palestinians will agree to accept arrangements that severely limit the sovereignty of the Palestinian state and damage the fabric of life in its designated territory.

Among the main security demands are:

- A demilitarized Palestinian state, including disarmament of the terror organizations.

- Overriding Israeli security responsibility: on land – freedom of action throughout the territory west of the Jordan River; in the air – full air space controlled by Israel; at sea – Israeli control of the territorial waters of the Gaza Strip; in the electromagnetic space – Israel will allocate frequencies for use by the Palestinian state.

- Strategic depth: Israeli sovereignty and security control of the Jordan Valley, strategic traffic routes; control of strategic sites (two sites under Israeli sovereignty – Tall Asur and Metzudot Yehudah, as well as Mount Eival warning station).

- Protective space to secure Ben Gurion Airport: Israeli sovereignty over the land controlling the airport and the tarmacs.

- Israeli control of the security perimeter: Under the plan, Israel will encircle all the sections of Palestinian territory and will control its external borders, where it will have responsibility for security checks (Allenby Bridge – crossing into Jordan, and Rafiah – crossing into Egypt). In the first stage, no port will be built in the Gaza Strip, and Israel will commit to allow Palestinian use of Israeli ports at Ashdod and Haifa, subject to absolute Israeli control of security checks.

- Adapting the security barrier to the new border: In addition to rebuilding the barrier based on the new border, Israel will have the right to approve all planning and zoning decisions for land use and construction on the Palestinian side based on its security needs.

- Close security cooperation between Israel and the Palestinian state’s security apparatuses: the plan rejects the integration of international forces in the security arrangements between the states, based on negative experience of the effectiveness of UN peacekeeping forces.

- Decisive Israeli authority to determine performance measures for the Palestinian security apparatuses, before any areas are transferred to their security control.

According to the plan Israel receives a comprehensive response to its security demands, but implementing the framework in accordance with conditions on the ground creates a long, winding border, isolated enclaves and villages, mix of populations – a situation in which it will be hard for the IDF to implement the security arrangements. Inter alia, it will be difficult to prepare for the ongoing and uninterrupted defense of long and narrow traffic routes (with no security breadth) reaching isolated settlements; there will be increased friction with Palestinian populations and security forces along these routes; and there will be additional challenges involved in the protection of isolated settlements, as well as entrances and exits and crossings between the Palestinian territories, and along the twisting border. Guarding the settlements and their lifelines, particularly those deep within Palestinian territories will require considerable reinforcement of IDF forces. In such conditions there will be only a slight chance for close and effective cooperation with the Palestinian security apparatuses. Moreover it will be necessary to move the security barrier to the new border line (involving huge expenditure); in southern Israel there will be a growing security challenge of weapons smuggling and infiltration by terrorists and extremists along the Philadelphi Axis from the Sinai Peninsula into Palestinian territory, which will be extended to enclaves in the Negev. Therefore, if the plan is implemented in its present format, it will be hard to ensure a better security situation than at present.

Economics

The economic portion of the Trump plan was presented at a workshop in Bahrain in June 2019. At its center is the establishment of an investment fund of $50 billion, of which $28 billion is for investment in the Palestinian Authority and Gaza Strip areas, and the rest for investment in neighboring countries, in order to enlist their support for the plan: $7.5 billion in Jordan and $9 billion in Egypt. The economic framework is intended to lay the foundations for an independent, functioning Palestinian entity, and also serve as an incentive to the Palestinian public to accept the plan and soften any opposition. The grant to the Palestinians will be distributed over a decade – $2.8 billion dollars. The difference between this amount and the total annual donations to the Palestinian Authority from donor countries, together with the UNRWA budget (the UN Palestinian refugee organization) is not large. The plan mentions almost two hundred projects in various fields, including infrastructure (such as the overland crossing between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank), health, law, education, and employment. In other words, the plan is extremely ambitious, although the sources of its funding are not clear. In addition, the timetables for promoting the most important objectives mentioned – doubling GDP, creating one million jobs, reducing unemployment to single digits in a decade – are unreasonable.

Moreover, the boundary between Israel and the future Palestinian state according to the plan – the long, twisting border and the enclaves of both sides – will make economic separation very difficult and require a unified customs framework, as there will be no other effective way to combat smuggling.

(The deceleration on the Deal of the Century)

The Palestinian Response

The Palestinians’ sweeping rejection of the plan is expected to place considerable problems in the way of implementation.

The Palestinian Authority and the PLO can be deemed “present by their absence” from the Trump plan, which presumes to determine the Palestinian national future. The significance of the proposed framework is a defeat of the Palestinian national struggle, because inter alia it undermines the belief that time is working in favor of the Palestinian national enterprise and that eventually the international community will force Israel to accept the Palestinian conditions for an arrangement. It is therefore not surprising that all the Palestinian factions have vigorously rejected the plan. As they see it, the plan and its implications pose an existential threat to their achievements and their vision of an independent Palestinian state that enjoys full sovereignty. It is hard to point to a Palestinian leader past or present who would agree to the outline of such a small, divided Palestinian state surrounded entirely by Israel, with its capital at the end of East Jerusalem. Representatives of the Palestinian people, who have so far rejected all offers of a final status agreement, cannot accept the Trump proposal, since its clear significance for them is surrender, and a concrete threat of the absolute loss of their public legitimacy.

Upon publication of the plan, an attempt was made by the Palestinian Authority and the Hamas regime in Gaza to coordinate their positions and ways to oppose the idea, particularly in view of the possibility of unilateral annexation of territory by Israel. However, the PA and Hamas were unable to overcome their disputes and conflicting views. Meanwhile, Mahmoud Abbas’s condemnation of the plan has resonated in the international arena and the Arab world. Despite his mild diplomatic success, in the domestic arena Abbas is the object of criticism because of his inability to lead significant international action against Israel on the one hand, and his avoidance of increased friction with the Israeli security forces on the other hand, and he is unable to foment popular protest. According to an opinion poll conducted by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research (PCPSR), 94 percent of respondents expressed opposition to the plan, yet there was no significant escalation in demonstrations in the West Bank or attacks on Israel. For the moment, Abbas is clinging to his policy of condemning terror and is not interfering in security coordination with Israel, for fear that outbreaks of terror in the West Bank will lead to a strong Israeli response and undermine the status and political achievements of the PA. But despite the relative quiet and lack of public enthusiasm for street demonstrations and friction with Israeli forces, unilateral annexation by Israel of territory in the West Bank could be expected to push Fatah and Hamas into a corner and impel them to resort to violence (although the scope and intensity of such a development would depend on the scope and location of the annexation).

Regional and International Responses

Other problems may arise in view of the lukewarm regional and international response to the Trump plan (although opposition is mainly due to the formulation of the plan without Palestinian involvement and the Palestinians’ decisive rejection of its contents).

Jordan

Jordan is the weak link in the inter-Arab system. The Hashemite Kingdom faces a serious dilemma – its economy and security depend on the United States, but it is very concerned that implementation of the plan will actually prevent a two-state solution, and then the idea of Jordan as the alternative Palestinian homeland will resurface. Moreover, Palestinian demographics within the Kingdom makes it hard to express a position that could be seen as damaging to the Palestinian people. In spite of this dilemma, King Abdullah contacted Mahmoud Abbas after the plan was made public, in order to support him and express Jordanian support for the idea of two states, based on the traditional paradigm that is accepted in the Arab world. At the same time, the Kingdom does not permit the expression of public criticism against the continuation of peace relations with Israel.

Egypt

Egypt’s official response did not refer to the terms of the plan but rather expressed support for the American mediation efforts and the attempt to advance a resolution of the conflict. Egypt’s main difficulty derives from the need to support the Palestinians, which it has done vis-à-vis the Arab League and a meeting between Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and Mahmoud Abbas, alongside Cairo’s wish to maintain good bilateral relations with Washington. Several elements of the plan suit Egyptian interests: the demilitarization of Hamas and return of the Palestinian Authority to power in the Gaza Strip; the idea of economic peace, and above all the promised investment of $9 billion in Egyptian development, subject to implementation of the Plan; the lack of influence on Egyptian sovereignty in northern Sinai; and the reference to Egypt’s security needs. The Egyptian criticism focuses on the fact that the plan was announced in the presence of one side only and it is therefore perceived as a political move by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

The Gulf States

Those who drafted the plan expected the Arab regimes that are close to the United States to make an effort to persuade the Palestinian leadership to show a positive approach and not reject the plan outright. But these expectations were not met, and in fact publication of the plan led the Arab and Muslim world to stand up to support the Palestinians’ position.. At the same time, in spite of criticism of the plan heard from the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and the Arab League, which officially rejected it, there is no complete agreement between the member states of those forums in this respect. Some even see it as a basis for negotiations, or alternatively, an unreasonable scenario, and therefore they do not see it as a reason to create problems for themselves with the Trump administration. However, not one of the states that expressed support for the plan has accepted it unequivocally. Representatives of the Emirates, Oman, and Bahrain who were present at the White House when the plan was unveiled claimed later that they were not familiar with its details and were invited to the event based on an assurance that the most important principles for the Arab world – a Palestinian capital in Jerusalem and the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip – were included. After the plan was announced, it was clear that its principles were far from the expectations of the Arab states, and that it proposed a change in Muslim status in the al-Aqsa Mosque and approval of Jewish worship in Haram a-Sharif. In spite of the close relations between the Trump administration and Saudi Arabia, the Kingdom did not express support for the plan or recognition of it as a basis for negotiations, and in conversation with Mahmoud Abbas, King Salman expressed unconditional support for the Palestinian people. Kuwait and Qatar had reservations about the plan, but praised the American administration for its efforts. In the face of Israel’s search for normalization with the Arab world over the last decade, there was clearly a mutual desire to promote relations based on shared strategic interests, but this is not enough for them to accept a peace plan based on the Trump framework.

The International Community

Most of the international community did not share Israeli and American enthusiasm for the plan, and it was rejected by a number of important entities and countries, although not always with condemnation. After the plan was rejected by the Arab League, a Kremlin spokesman, Dimitri Paskov, said that it ran contrary to UN resolutions on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and could not be implemented as far as the Palestinians and the Arab world were concerned. The European Union has difficulty formulating a position that is acceptable to all its member states and did not formulate an official stance for or against the plan, although the EU High Representative for Foreign and Security Affairs, Josep Borrell Fontelles, mentioned the organization’s commitment to the two-state solution based on the 1967 lines, with an independent and contiguous Palestinian state, and thus in effect rejected the proposed formula. At the same time, the EU sees the plan as an opportunity to renew Israeli-Palestinian talks. Furthermore, criticism of the plan has also been voiced in the US Congress: 107 Democratic members of Congress submitted a letter to President Trump, arguing that the plan would not enable the creation of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. The authors claimed that the plan lacked good will and therefore could not be treated seriously.

Implications for Israel

The text of the plan outlines a final status agreement with room for negotiations only on the details of implementation but not the core issues, yet at the same time asserts that the plan describes a “vision.” These mixed objectives were also expressed by American administration officials – including President Trump himself while presenting the plan, and US Ambassador to the UN Kelly Craft during discussion of the plan at the Security Council – who defined it as a “vision” that calls on Israel and the Palestinians to start talks about its details and implementation. Indeed it is possible that a mediator in the talks will propose this “end state” as a bridging proposal, if there were agreement in principle between the parties on the outline of a solution. However, this situation does not currently exist in the Israeli-Palestinian arena due to unbridgeable gaps in the opening positions of the parties. The objective of ending the conflict and all claims, as defined in the plan, is not practical as long as neither side truly believes that the other side is making a supreme effort, in good faith, to respond to its needs. Therefore, the plan embodies a large degree of naivete, reflected in the belief that the parameters can indeed bring about a new regional order, shared by Israel and the moderate Arab states, and that an ethnic-emotional-instinctive conflict, which characterizes relations between Israel and the Palestinians, can be resolved by means of a far-reaching real estate offer and economic bait.

Although the framework is not a fair test for the Palestinians, its rejection by them – following their rejection of proposals previously on the negotiations table – reinforces the Israeli narrative of the lack of a partner for peace. In view of the weak negative reactions to the plan in the region, and particularly because its presentation did not arouse widespread violence in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, it is possible that elements in Israel that are looking for an opportunity to annex land will work energetically to launch the process. This will deepen the chasm between the sides and increase the difficulty of finding any future formulation for practical opening terms to restart talks. Moreover, the plan also threatens to seriously undermine the existing stability, however compromised it currently is, particularly if Israel decides to implement the parts of the plan that suit it without a serious effort to show flexibility toward the Palestinians in order to persuade them to get on board.

In addition, the plan does not offer substantive leverage to the Palestinians to establish a functioning, stable, and responsible state, or to bridge the existing rift in the Palestinian system, mainly between Fatah and Hamas and between the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. It lacks a formula to deal with the split in government and with the demand to restore the Strip to control of the Palestinian Authority and to disarm Hamas as a condition for the establishment of the Palestinian state. Even if the parties involved can overcome all the obstacles, if Israel and the Palestinians can fulfill all the conditions and the Palestinian state is established, it will still be divided into six cantons, making it very hard to achieve sustainable stability (history shows that countries without contiguous borders tend to break up). The expected problems to be faced by the Palestinian leadership trying to control such a complicated territory will force Israel to be responsible for the basic living conditions of about 3 million Palestinian in the West Bank – Judea and Samaria and Jerusalem – as well as another 2 million in the Gaza Strip (even after the disengagement). The security, economic, civil, and political burden on Israel will then be extremely heavy. Therefore, even implementation of the plan offers an interim solution only. Israel will have to continue managing the conflict, and in far more complex conditions than at present.

However this is the first time that an American administration has accepted Israeli demands for security arrangements and for annexation of all settlements – the settlement blocs and the Jordan Valley up to the heights that control the Valley from the west. As US Ambassador to Israel David Friedman suggested, there are two deals: the actual “deal of the century” and the “deal within the deal.” Israel would wait until a committee of six, three Americans and three Israelis, complete the work of adapting the map proposed by the Trump plan to the reality on the ground, thereby making it feasible, and would freeze construction in areas earmarked for the Palestinian state, and then the US would recognize Israeli sovereignty over areas that are not intended for the Palestinian state. In other words, the American administration is setting up the conditions that will allow Israel to annex land without Palestinian consent.

The plan embodies a genuine, substantive threat to the vision of a Jewish democratic state, since it would mean absorbing almost 450,000 more Palestinians within the boundaries of Israel. If following Israeli annexation the Palestinian Authority collapses, Israel will have to take responsibility for the entire Palestinian population. The unavoidable consequence will be a slide into a one-state reality. This will also accelerate the already existing trend, primarily among young Palestinians, of seeking a one-state solution and claiming equal rights for all.

Furthermore, under the conditions of the proposed map, in return for the land designated to be under its sovereignty, Israel is required to hand over significant territory in the western Negev with a possible addition of the Triangle area – Israel’s “narrow waist” (although the probability of implementing this option is nonexistent). In which government forum did Israel decide that the annexation of isolated settlements deep within Palestinian territory is more important than retaining land in the Negev – providing strategic depth for Israel – and in the Triangle, in the heart of Israel? In which forum was there a discussion of the complex, weighty, and hugely expensive consequences of the need to secure a border of about 1,400 kilometers, while adding about 450,000 Palestinians within Israel’s area? All this without involving the Israeli security establishment or instructing its staff to prepare for the various implications.

Options for Israel

Following the publication of the Trump plan, Israel faces three alternatives for action. All three will be relevant after the elections and the inauguration of a new government:

- Looking at the plan as an opportunity, perhaps one-time, to shape the reality of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on Israel’s terms: In this situation, the rejection of the plan by the Palestinians, supplemented by the American backing, will be perceived by Israel, internally and also to some extent externally, as legitimacy to implement components of the plan according to its own interests. Israeli law will be applied in the Jordan Valley and the settlements (based on the framework in the plan) in one swoop, while completely ignoring Palestinian and Jordanian objections as well as international opposition. The consequences: closing the door to any future agreed settlement; undermining the special relationship with Jordan and possibly damaging the peace relations with it; increased terror and violence from the Palestinian side; a slowing down of normalization processes with Arab states; and isolation and even a possible boycott by the international system. The most dangerous response to unilateral annexation would be the breakdown of the Palestinian Authority, which would then “return of the keys” to Israel – leading to a one-state reality, with all the negative consequences for Israel in terms of its security, economy, society, and ideology.

- Acceptance in principle of the plan, without taking any practical steps until the new Israeli government is in place and the Palestinian Authority expresses willingness to resume negotiations: Israel could set new conditions for promoting an arrangement based on the Trump plan, including: seeking to establish mutual trust; strengthening security cooperation; improving economic and civilian conditions in the Palestinian Authority; deepening and broadening relations between Israel and Arab countries, specifically Egypt, Jordan and the Gulf States; reinforcing regional involvement in relations between Israel and the Palestinians; and recruiting aid from the Arab world in order to promote conditions for a sustainable and functioning Palestinian state (also in return for Israel’s refraining from any unilateral annexation). The significance: the Trump plan would remain “on the shelf,” with American backing and as a new benchmark for future talks, while firmly anchoring Israel’s essential security requirements as formulated in the plan, and also while encouraging Israel to show flexibility regarding the territorial and functional dimension of the Palestinian entity.

- Israel will see the plan as a strategic framework aiming at separation from the Palestinians, while striving for cooperation in implementation of transitional arrangements: Israel will call on the PA leadership and the PLO to study the plan and return to the negotiating table on that basis. At the same time, it will be clarified that Palestinian refusal to participate in talks will lead to gradual implementation of parts of the plan that advance geographic and demographic separation, but still leave the door open to negotiations and coordination with the PA. Without progress from the Palestinian side, Israel will begin incremental annexation of settlements and settlement blocs where there is public consensus and where they suit the trend towards separation. In return, Israel will grant the Palestinian Authority land of equal value in Area C (in areas settled by Palestinians, thus creating Palestinian territorial contiguity). If the Palestinian Authority retains its refusal to renew talks, Israel can continue to shape a reality of territorial, political, and demographic separation from the Palestinians, based on A Strategic Framework for the Israeli-Palestinian Arena, published by the Institute of National Strategic Studies (INSS). The INSS Plan has two goals: one is to improve the strategic position of the State of Israel; the second is to avoid a steep decline toward a one-state situation. The objective is to shape a better reality that will facilitate the opening of future options for ending Israeli control of Palestinians in the West Bank, and ensure a solid Jewish majority in a democratic Israel. In other words: the framework is designed to prepare the ground for a two-state reality, in which the Israeli ethos of a Jewish, democratic, secure, and moral state can be realized.

In the long term, the first option embodies many risks for the State of Israel from all aspects – its security, economy, civil society, international, and regional standing – and could lead to a one-state reality. In contrast, the second and third options (the third could be implemented after the second) could shape the conditions for separation from the Palestinians, and the creation of an enhanced strategic reality for Israel.