Historical Background

Unlike any other region of the world, Europe has had the most intimate, impactful and longest-lasting relationship with contemporary Israel and its origins. As the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity and with the Holy Land’s valuable strategic location, Europe’s rulers and popes established covetous connections with the land on the shores of the eastern Mediterranean, especially the Galilee, Bethlehem and Jerusalem. Antisemitism, springing episodically from all corners of Europe, catalyzed Jewish migrations. European persecution of Jews marginalized their lives and ironically sustained communal survival. Both realities eventually led to the percolation and development in 19th century Europe of modern political Zionism.

Having made promises to Arabs, Jews, and one another during and after World War I, the British and French ultimately carved up the Middle East into trusteeships or Mandates for themselves, with the British governing Palestine until May 1948. Jewish immigration in the periods of the most significant growth, between 1882 and the founding of Israel, came primarily from European and Eastern European areas. While the Jewish national home grew significantly in Palestine before the beginning of World War II, the unique circumstances of the Holocaust had significance in generating the world’s sympathy for establishing Israel.

With the Arab economic boycott of Israel’s goods and services, denying its commercial outlets to proximate neighbors, Europe became and remains Israel’s primary trading partner. Since the 1960s, Israel has maintained a twofold relationship with Europe: one that is bilateral between Israel and individual countries, and the second that connects Israel to the European community as a whole. The bilateral is heavily dependent on who the leader of a European country is at a particular moment and whether Israel is in competition with that country for commercial markets; the multilateral is frequently dependent upon international matters or specifically Middle Eastern regional issues.

During the Cold War, Israel found itself on the side of European democracies in their political struggles with Moscow. In the early 1950s, Germany provided valuable monetary reparations to individual Israelis and to the state. France, Britain and Israel colluded in the Suez War, which failed to bring down Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser but kept Israel aligned with both London and Paris in obtaining needed military supplies. Additionally, France provided Israel with the primary know-how and technology for building its nuclear weapons program. After the June 1967 war, French President Charles de Gaulle blasted Israel for starting a defensive war, causing those bilateral relations to sour. In the October 1973 war, Europe as a whole shut down use of its airspace and airports for American resupply of Israel and issued a scathing statement against Israel, in large measure because of fears of the loss of oil supplies from Arab producers.

Israel’s 1975 Free Trade Agreement with Europe went beyond trade to include cooperation in scientific matters and touched on possible exchange of technological know-how. The enlargement of what is now the European Union in the early 1980s, including Spain, Portugal and Greece, slowed Israel’s trade with the Common Market because these countries directly competed with Israeli agricultural exports. In November 1995, Israel signed an Association Treaty with the European Community. Implementation of the treaty was delayed in great measure until 2000 because of stark disagreements between EU countries as a whole and the Israeli Likud governments that had previously frozen the negotiation process with the Palestinians.

Episodic Changes in Israeli-European Relations Since 2000

Since 2000, European opposition and support for Israel swung like a pendulum. European-Israeli relations had been in decline by the time of 2010-2011 “Arab Spring” mostly because of Israel’s expanded settlement construction, but the downslide accelerated when, in November of that year, a resolution came before the U.N. General Assembly to upgrade Palestine’s status in the body to “non-member observer state.” Whereas Palestine’s bid to join UNESCO, the United Nations; cultural arm, had been endorsed by few European states in 2011, Israeli-European relations had soured enough in 2012 that eight European countries that had voted no the previous year now voted in favor or abstained. Noting the change, prominent news outlets ran headlines that read like epitaphs for Israeli-European cooperation. The Christian Science Monitor announced, “Israel Faces Lowest Point in Europe Relations in Decades.” Haaretz explained, “How Israel Lost Europe’s Support,” and The Washington Post told of “The Growing Divide between Israel and Europe.” Portended changes in Arab governance, or at least its initial failures, slowed down European capital distancing to Israel. There was collective uncertainty of the region’s stability, with Israel standing as a reliable ally, even if its policies toward the Palestinians were not embraced.

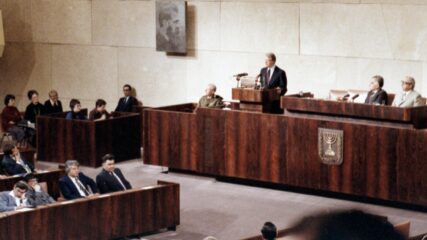

In the ensuing three years, these heightened tensions between Europe and Israel continued to mount, as a series of crises threatened to strain the relationship to breaking point. In 2013, the EU, much to Israel’s outrage, issued a directive prohibiting funding for Israeli firms and institutions connected in some fashion to the settlements. So exasperated was Israel that, in retaliation, Jerusalem suspended cooperation with the EU in the West Bank, barring access to EU personnel and aid workers. Israel also cancelled the 2013 meeting of the Israeli-European Association Council, a body established in 1995 to strengthen European-Israeli relations. It would be 10 years until the council, whose meetings were intended to be annual, would convene again. The increased tension was on full display in the Knesset in early 2014 when rightist parliamentarians walked out in protest as the president of the European Parliament addressed the chamber. Nor did European high officials hold back their criticism later that year when Hamas and Israel fought the third of their five wars.

Emboldened by President Barrack Obama’s own criticism of Israel and his suspension of munitions shipments to the Jewish state, European leaders and ministers denounced Israel unsparingly and embargoed arms exports. Then, both in 2014 and 2015, draft EU position papers were leaked to the press, revealing that Brussels was even weighing sanctions against Israel, including rolling back its free-trade agreement with Israel. Another blow to the relationship came at the end of 2015 when the EU mandated that labels on goods and produce from Israel distinguish between those from Israel proper and those from the West Bank. Israel retaliated by freezing cooperation with all EU bodies involved in “the diplomatic process with the Palestinians,” as the Israeli Foreign Ministry described the suspension.

But since this low ebb of European-Israeli relations, the tide has turned, and events have conspired to improve European-Israeli relations markedly. The reasons for the reversal are several:

- Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s efforts in the latter half of the 2010s to set up a bloc of Central and Eastern European countries as a counterweight to the unfriendly countries of Western Europe.

- Growing diplomatic self-assertion by post-Communist European states that acceded to the EU in 2004, 2007 and 2013.

- Rise of nationalistic populism in Europe and the ascent of the European right.

- Recognition of the benefits of cooperation with Israel in various sectors, including security, technology and energy.

- Desire for closer relations with the United States (particularly during the Trump era), closer relations with Israel being a means to this end.

- Stagnation of the Israeli-Palestinian peace process since 2014 and the drift of the Palestinian issue to the margins of international attention before Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023, massacre.

- European backlash to the surge of terrorist attacks in Europe between 2015 and 2017.

- European backlash to the mass influx of Muslim migrants in 2015 and 2016.

- Yair Lapid’s bid as foreign minister in 2021 and as prime minister in 2022 to repair Israel’s relations with the EU.

- Increasing frustration with Palestinian division and with the corruption and dysfunction of the Palestinian Authorit.y

The most significant change has come about in what Netanyahu often calls “New Europe,” the former Communist states of Central and Eastern Europe that joined the EU starting in 2004. In the latter half of the 2010s, Netanyahu set about courting “New Europe” in the hope of making it a counterweight to “Old Europe.” Far from concealing this scheme, he declared it openly, declaring on a trip to Lithuania in 2018, “I am also interested in balancing the not always friendly attitude of the European Union towards Israel so that we receive fairer and more genuine treatment. I am doing this through contacts with blocs of countries within the European Union, Eastern European countries, [and] now with the Baltic countries, as well, of course, with other countries.”

With this objective in view, Israel has forged particularly close ties with the so-called Visegrád Group, a bloc of four states (Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia) that have been avid to harness Israeli expertise in the fields of high technology, research and development, and innovation. Israel has found receptive partners elsewhere in “New Europe” and developed cordial relations with the countries of the Balkan Peninsula (Croatia, Bulgaria and Romania) and the Baltic Sea (Lithuania, Latvia and, more recently, Estonia). Nor has the rapprochement been limited to former Communist countries. Ever since Israeli-Turkish relations declined to their nadir in 2010, Israel has drawn ever closer to Turkey’s adversaries in southeastern Europe, Greece and Cyprus. With Turkish sensitivities no longer a concern, Israel’s relations have flourished with the two Greek-speaking states, strengthened by defense procurement, joint military exercises and, since 2020, a de facto energy-sharing alliance.

Since 2016, the thaw in Jerusalem’s relations with Europe produced tangible gains for Israel. Beginning in July of that year, the European Union’s Foreign Affairs Council, a body comprising all the member states’ foreign ministers, broke with its custom of issuing “conclusions” critical of Israel at its monthly meetings. The change came about thanks to obstructionism by the foreign ministers of friendly countries in “New Europe.” Then, in 2017, the EU’s 705-strong European Parliament passed a resolution for the first time that struck a balanced tone in apportioning blame for the impasse in the peace process. The resolution denounced terrorism against Israelis and deplored the deficiencies of the Palestinian Authority (e.g., canceling elections and corruption). In itself, the resolution was no scathing reproach of the Palestinians, but coming from a parliament that has been inclined to forgive rather than criticize Palestinian misdeeds, it was a milestone.

With the peace process stalled since 2014 and with President Donald Trump occupying the White House starting in 2017, the Palestinian cause receded from international attention and, consequently, from the top of Europe’s diplomatic agenda. The Europeans appeared to be coming to terms, however unwillingly, with the stalemate in the peace process and with the futility of new Israel-Palestinian peacemaking initiatives. Not since January 2017, when France convened its resoundingly ineffective peace conference, have they made another doomed push for a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The urgency with which the Europeans had always pressed for Israeli-Palestinian peace had given way to a grudging acquiescence in the peaceless status quo.

Meanwhile, Israel’s friends in Europe continued working against EU measures unfavorable to Israel. In 2018, France spearheaded an effort to coordinate an EU-wide statement denouncing the relocation of the American embassy to Jerusalem, but some of Israel’s allies in “New Europe” intervened to quash it. Then, in 2020, amid concerns that Israel was preparing to annex parts of the West Bank, the EU again polarized over an appropriate response, splintering between the mostly Central and Eastern European states aligned with Israel (Austria, the Czech Republic, Cyprus, Greece, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia) and the largely Western European countries ill-disposed to Israel (Belgium, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Spain). As is their custom, Germany and Italy tried to steer a middle course. In any case, collective action against Israel was again thwarted.

After years of Israeli efforts to build closer relations with Central and Eastern European countries, countries that were growing ever more confident in pursuing their own diplomatic course, a predictable pattern had evolved in the EU. Whenever policy toward Israel was at issue in the 27-country body, EU member states would coalesce into two camps: one sympathetic to Israel (largely in Central and Eastern Europe) and one unfriendly to Israel (largely in Western Europe). Elections and changes in government may move a country from one camp to another, but the members of the two camps are, for the most part, consistent.

The evolution of Europe’s posture toward Israel since 2016, though gradual and subtle, was such that Europe’s response to the 2021 Israel-Hamas war presented a notable contrast with its response to the last war between the two combatants in 2014. Whereas European rhetoric during the 2014 war incriminated Israel while exonerating Hamas, European officialdom’s statements about the war in 2021 were more measured and more balanced. During this round of hostilities, Israel was not reflexively made out to be the aggressor; full-throated declarations of support for Israel even came from many European leaders and foreign ministers — namely, those of the U.K., France, Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Romania and the four Visegrad countries.

Despite the hostility of some EU members and the anti-Israeli animus of the organization’s top diplomat, Israeli cooperation with the EU today is more extensive than ever. Israel and the EU — which remains Israel’s largest trading partner, with about a third of Israel’s imports coming from the EU and a quarter of its exports going to the EU — have concluded several landmark agreements in the past few years. The “Open Skies Agreement,” effectuated in 2018 and ratified by the European Parliament in 2020, permits direct flights between all of Israel’s and the EU’s airports. Easing travel and reducing airfare, the accord has led to a surge in bilateral tourism. Israel’s renewal in 2021 of its membership in the EU’s Horizon Europe program for research and development enables Israeli researchers and firms to secure grants and, according to the Israeli Foreign Ministry, “to participate in any part of the European R&D program on equal terms to those of EU member countries’ entities.” Israel’s 2022 Memorandum of Understanding with Egypt and the EU, signed in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, provides for future Israeli exports of natural gas to the 27-nation bloc. Although Israeli natural gas has not yet begun flowing to Europe, it is notable in itself that Brussels looked to Israel to reduce continental dependency on Russian natural gas.

In parallel with expanding trade, Israel’s relations with the EU have improved on the diplomatic front. For the first time in 13 years, Israel’s foreign minister was invited in 2021 to attend a meeting of the EU Foreign Affairs Council at the invitation of the EU’s foreign minister, and, for the first time in 10 years, the Israeli-European Association Council, the principal coordinating body between Jerusalem and Brussels, convened after their formerly annual meetings were suspended in 2013. And while the EU’s top diplomat, Josep Borrell, is, like his predecessors, no friend of Israel, the EU’s president since 2019 is the staunchly pro-Israel Ursula von der Leyen.

European Public Opinion and Antisemitic Outbursts

European public opinion toward Israel is far from unanimous, but a few generalizations may nevertheless be made. For its part, Western Europe has consistently proved more sympathetic to the Palestinians than to Israel. In 2007, the Pew Global Attitudes Project surveyed respondents in Germany, Sweden, France, Spain, Italy and U.K. and found that only in Germany did Israel garner more sympathy than the Palestinians. A YouGov poll 16 years later (May 2023) registered the same breakdown.

In these six countries, as elsewhere on the continent, the October 7 attacks occasioned a surge of sympathy for Israel. A December 2023 YouGov poll recorded a sharp spike in sympathy for Israel in Germany, Sweden, France, the U.K., and even in Europe’s most tenaciously anti-Israel country, Spain. The increase in Italy, however, was more a step up than a leap. If sympathy for Israel rose in Western Europe in the wake of the October 7 massacre, it flagged for the Palestinians. Yet, as Israel’s campaign to root out Hamas dragged on, the trend inverted, and sympathy for Israel started to sag while sympathy for the Palestinians began to climb.

In Eastern Europe, by contrast, attitudes to Israel are markedly more favorable, although, in some countries, they are harbored alongside adverse opinions about Jews. In Poland and Hungary, in particular, Israel enjoys considerable popular support even as Jews continue to be viewed with disfavor by a not inconsiderable segment of the population. There is no such contradiction in the Czech Republic, where support for Israel is significant and antisemitism marginal. To be sure, antisemitism remains a European-wide scourge, and the number of assaults on Jews has soared since October 7, particularly in Western European countries with significant Jewish communities — among them, France, Germany, Belgium and the U.K.

The Rise of the Pro-Israel European Right

In present-day Europe, more so than in America, exactly where a government or party stands on the political spectrum more often than not predicts its orientation toward Israel. This was not always so, but in today’s Europe, there can be no doubt that a rightwing persuasion translates to a more favorable line toward Israel. There are exceptions, of course, but they are vanishingly few. The European Coalition for Israel (ECI), a Brussels-based Christian Zionist lobby, analyzed the voting patterns of political parties across Europe from 2019 to 2022 and found that the ten parties in Europe with the most pro-Israel electoral record were exclusively on the right (half center-right and half far-right). Conversely, the ECI found that Europe’s ten most anti-Israel parties are all on the left — all a part of “The Left” bloc in the European Parliament.

In some measure, there is a natural affinity between Israel and the European right. Many of the characteristics that distinguish Israel as a state are shared, coveted, or admired by the European right: Israel’s unapologetic nationalism and self-assertion as a nation-state, its religiosity, its partnership with the United States, its Euroscepticism, and its bold resistance to Islamism. The contemporary European left, by contrast, rejects all of the foregoing, and it is no coincidence that its relations with Israel range from grudgingly cooperative at best to unreservedly hostile at worst. This is not to say that right-wing governments in European are reflexively pro-Israel. The Tories in Britain are a case in point. Britain’s Conservative Party, considered on its own terms, may not appear overwhelmingly pro-Israel, but compared to the British Labour Party, it most certainly is. The same is true of Finland’s incumbent government, led by the center-right National Coalition Party (NCP). The NCP is far from consistent in its support of Israel, but its left-wing rival, the Social Democratic Party of Finland, is positively hostile to Israel.

Nor is this to say that antisemitism on the European far right is a thing of the past. It used to be that the far right was the preserve of Europe’s antisemites. As opponents of the Jewish people, arch-rightists were opponents of the Jewish state. Since the far-right parties (with the exception of the Dutch Freedom Party), are tainted by fascist origins or fascist policies, the Israeli Foreign Ministry has upheld a longstanding boycott of Europe’s far-right parties, prohibiting Israeli diplomatic personnel from meeting with their members. In recent years, however, some of these parties have urged support for Israel and denounced antisemitism, prompting the Israeli Foreign Ministry, over the objections of many (including those within its own ranks), to relax the boycott.

Now, whether the far right’s about-face represents a genuine change of heart or is merely an exercise in image laundering is, in each case, a matter of some dispute. France’s far right National Rally, once an avowedly antisemitic party, has evolved since 2012, when the leadership of the party passed from its founder to his daughter, Marine Le Pen. Under her leadership, the party has sought to dissociate itself from antisemitism, expelling antisemites (including her father) and denouncing antisemitism. Many French Jews nevertheless remain leery of Le Pen and her party, and her habit of denying French complicity in the Holocaust gives good grounds for their suspicion. The zealously pro-Israel Sweden Democrats is another political party on Europe’s far right that claims to have exorcized antisemitism from its program and its ranks — this after a leadership change in 2005. Like French Jews vis-a-vis Le Pen’s National Rally, Swedish Jews have held aloof from Sweden Democrats, whose rhetoric and programmatic opposition to circumcision have alienated them. Hungary’s Jobbik Party and Austria’s Freedom Party, two far-right parties that just 10 years ago were both avowedly antisemitic and anti-Israel, have attempted a similar self-rehabilitation and claimed a similar transformation, but their supposed rebirth is more recent and even less convincing.

Whatever the European far right’s line toward Jews and Israel today, it remains that the European right is, in general, far more supportive of Israel and better disposed to Jews than the European left. Germany’s two pro-Israel left-wing parties — Die Linke and the Social Democratic Party — have become total outliers among their ideological confederates elsewhere on the continent. What’s more, not a few leftist parties in Europe justified, celebrated, or refused to condemn the October 7 atrocities. In France, for example, the far-left party France Unbowed, with 74 seats in Parliament, not only refused to condemn Hamas, but also refused to take part in a mass rally in November 2023 against antisemitism. Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, by contrast, participated.

In view of the European right’s more supportive posture toward Israel, the rise of the right in Europe in the past decade has been a boon for Israeli-European relations. Israel has enjoyed warm relations with the center-right governments in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, and Poland (since 2023), as well as with the far-right government in Hungary. Israel’s relations with the Nordic countries, a bloc traditionally hostile to Jerusalem, have even improved in recent years, after right-wing coalitions were sworn in Sweden in September 2022 and in Finland in June 2023. Bemoaning the shift in Sweden’s line toward Israel, Palestine’s ambassador to Stockholm told a local newspaper that Sweden “is no longer the country I knew.” As for Southern Europe, Israel’s relations with Croatia, Bulgaria and Greece have flourished under their center-right government, and its relations with Italy have improved markedly since the right-wing coalition of Giorgia Meloni came to power in October 2022.

Europeans and Israel Since October 7

The European response to the October 7 massacre has thrown into sharper relief three interrelated changes in the continent’s relations with Israel: unprecedented division over Israel, a more favorable orientation toward Israel in general, and a European right that is reliably pro-Israel. To the atrocities of October 7, Europe’s response was one of widespread sympathy for Israel. Blue and white were projected onto the Eiffel Tower, No. 10 Downing St. and the Brandenburg Gate while the Israeli flag was hoisted above the European Parliament and several national parliaments. Expressions of condolence and consolation poured in from all quarters of the continent, and European leaders hurriedly made solidarity visits to Israel. Among these eminent visitors were German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, French President Emmanuel Macron, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis. The Greek premier assured his hosts, “I come here not just as an ally but as a true friend.”

Still more remarkable was a resolution in support of Israel passed in the European Parliament — remarkable both for the wide margin by which it passed and for the text of the motion itself. Carried by a vote of 500 to 21, the resolution endorsed Israel’s declaration that Hamas had to be “eliminated.” Not only is the acceptance of, let alone support for, such “bellicosity” is atypical in contemporary Europe, but with this resolution, the EU was endorsing the liquidation of a group that it had not even considered a terrorist organization between 2017 and 2019.

Another vote, though in a different body, within the war’s first month reflected the recent warming of Israel’s relations with the EU. On October 27, a resolution calling for a “truce” was put to a vote in the U.N. General Assembly. Twenty-two European countries abstained, four voted against it, and only eight voted in favor. Among the abstaining European countries were three that had formerly voted against Israel at the U.N.: Sweden, Finland and Estonia. As the war dragged on, European support for a cease-fire mounted, yet European division over Israel had never been starker. “I have never seen this kind of crossfire on EU foreign policy,” confided an EU diplomat to The Financial Times. “It’s a cacophony.”

On December 13, the U.N. General Assembly again voted on whether to endorse a cessation of hostilities in the ongoing war, only this time it was a “ceasefire” rather than a “temporary truce” that was at issue. The high Palestinian death toll had eroded European support for continuing the war, but even then, more than two months after the war had begun, two European countries voted no and 10 abstained.

Although by February 2024, the foreign ministers of every EU member state except Hungary had come to favor a cease-fire, Israel’s friends in Europe continued their support in other ways. After it emerged in late January 2024 that UNRWA staff had participated in and rejoiced over the October 7 massacre, the EU’s executive branch, the European Commission, and a number of European countries (Britain, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Finland, Estonia, Austria and Romania) suspended funding the U.N. agency. To be sure, most of these countries would resume funding weeks later in response to the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, but in early April the European Parliament adopted a number of resolutions denouncing UNRWA. The EU legislature took particular aim at UNRWA’s antisemitic indoctrination, even citing it as a cause of the war Hamas unleashed. A German member of the European Parliament declared that “education to [sic] hatred has direct and dramatic consequences on the security of Israelis, as well as the perspectives of a better future for young Palestinians. Therefore, the EP requests the Commission to closely scrutinize that no UNWRA funds are allocated to the use of such hateful materials.”

Israel’s friends in Europe continued arms exports throughout the war. It should be noted that about a third of all Israeli arms are sourced from Germany and about five percent are from Italy; the rest of Europe’s contributions to Israel’s arsenal trifling, consisting mostly of ammunition and spare parts. As Israel’s two main European arms suppliers, Germany and Italy have defied the appeals of the U.N. and part of their own populations and kept the pipeline of weapons flow; the U.K., for its part, despite the negligible volume of arms it furnishes Israel with, has also refused to stop sending military hardware to Israel. The Netherlands supplied spare parts for Israel’s F-35 fighter jets until a Dutch court in February ordered a halt to the shipments, over the objections of the government.

Will Israel’s Improved Relations with Europe Hold?

Geopolitics rests, not on a solid foundation, but on shifting sands, and relations between countries can change suddenly and drastically. Turkey and Iran, for instance, had been Israel’s closest regional partners against the Sunni Arab states for decades, but today, the Sunni Arab states are Israel’s closest regional partners and Turkey and Iran are its worst regional enemies. Similarly, Greece, the only European country to vote against the 1947 U.N. partition plan, fiercely opposed Israel for more than a half-century. But the same country that had thrown its full weight behind the PLO and refused to establish diplomatic relations with Israel until 1990 is now one of Israel’s closest partners.

The trajectory of Israel-European relations is neither a straight line up nor down. Fear of Iranian toxic foreign policy remains high as does concern about containment of Islamic radicalism again emerging suddenly in European countries. Care is taken to be ‘appropriate’ with Iran. The outcome or non-outcome to a conclusion of the Hamas-Israel War, Palestinian civilian impact from the war, the Hamas hostage keeping process, oil requirements from the region for Europe, the politics of the Palestinian future both internally and vis a vis Israel, as well as European trade with Israel all shape the European-Israel relationship’s future. Evidence of Europe’s lack of unanimity on Israeli-Palestinian matters was demonstrated in the April 18, 2024, U.N. Security Council vote to recommend full United Nations Membership for a State of Palestine. There were 12 votes in favor; the U.S. cast a negative vote, with Switzerland and the U.K. abstaining. The resolution did not pass. While there was some European support for the resolution, most of Europe did not want to impose a political conclusion on the issue, rather, most countries preferred Washington’s view of negotiated rather than unilateral devised outcomes to the conflict.

— Scott Abramson and Ken Stein, April 2024