Yohanan Plesner, Israel Democracy institute, February 10, 2020

With permission, read full article at IDI.

Introduction

On March 2, Israelis will head back to the polls for a third time in twelve months. This previously unimaginable situation has left many asking: How did we get here? The short answer is that, perhaps in an uncharacteristically surprising fashion for politicians, everyone kept their promises. Benny Gantz turned down all offers that would mean sitting with an indicted prime minister; Benjamin Netanyahu stayed true to his pledge not abandon his right-wing and religious partners; and Avigdor Liberman kept his word to only sit in a broad unity government.

Going forward, Israelis are wondering what if anything, will be different this time around? Will the newly publicized Trump peace plan prove to be a boon for Benjamin Netanyahu and help his Likud party succeed in forming a government after having failed to do so following the past two elections? Will Netanyahu’s official indictment, that was finally been presented to the Jerusalem District Court on the same day on which Trump’s plan was published, convince voters that it is time to move on and put their trust in Benny Gantz and his Blue and White party?

These two events would have been considered momentous game-changers in any past campaign, and the effects of the Trump plan in particular merits full analysis once we better understand whether any unilateral steps will be taken in the time remaining before the election.

What we do know is that it is very likely that we will be seeing similar results. Thus, to achieve a stable outcome, the two largest parties – Likud and Blue and White – will need to find a way to finally sit together in a unity government. Alternatively, Israelis might very well find themselves doing this all over again, in a fourth election in August.

What to Look Out For

As we enter this last phase of the election, from now until Election Day, the fight is now focused on who sets the agenda. Gantz and his Blue and White Party want the electorate to focus on Netanyahu’s legal troubles and on the prospect of a sitting prime minister attending his trial in Jerusalem’s District Court in the morning, and then heading to his office to convene the cabinet in the evening. They know that Israelis, almost completely across the political spectrum are uneasy about the prospect of business as usual, as Netanyahu’s legal predicament worsens. Blue & White hopes to ensure that from now until March 2nd, the front pages of the morning papers and the evening news broadcasts focus on Netanyahu the defendant and on the alternative that Gantz and his colleagues present.

For the Likud, the plan is to focus on their own strengths – the relative security and stability Israelis have enjoyed during the last ten years that Netanyahu has served in office. This is why the Trump peace plan and the possibility of annexation (or more correctly, extending Israeli sovereignty) over parts of the West Bank, is back in the headlines. Netanyahu first promised to extend Israeli sovereignty in the Jordan Valley in the weeks leading up to the second round of elections in September, saying that it would be one of the first items on the agenda of the government he hoped to form. He knew then, and he knows now, that this issue not only enjoys popularity among his right-wing base, but also among the more hawkish members of the Blue and White party. This creates an added bonus for the Likud, as they seek both to placate their base and perhaps split the main opposition at the same time.

We also know that that annexation is only one piece of a larger plan. As prime minister, even one sitting at the head of a government that has not received a vote of confidence from the Knesset, Netanyahu has enormous sway over matters of diplomacy and security. The Trump plan and the ripples it is already causing are excellent opportunities for Netanyahu to focus on what he and his supporters believe is his greatest asset —that is, his ability steer the ship of state through turbulent regional and international waters.

While the so-called ‘deal of the century’ may threaten to upset the more extreme elements of the right-wing base, since it implies some possible Israeli concessions, the very fact that the Israeli voter could focus on Netanyahu the statesman as opposed to Netanyahu the defendant, is a net gain for the Likud.

Who Will Show up?

Once the campaigns are over and March 2nd is upon us, the focus will shift to voter turnout. It is impossible to predict how Israelis will react to this third election and if they will show up at the polls. IDI’s latest survey indicates that the public is not following this campaign as closely as in the previous round. Still, in September the pundits were surprised by the amount of faith shown in our democratic system, with voter participation actually increasing to 70% from 68% in April’s election.

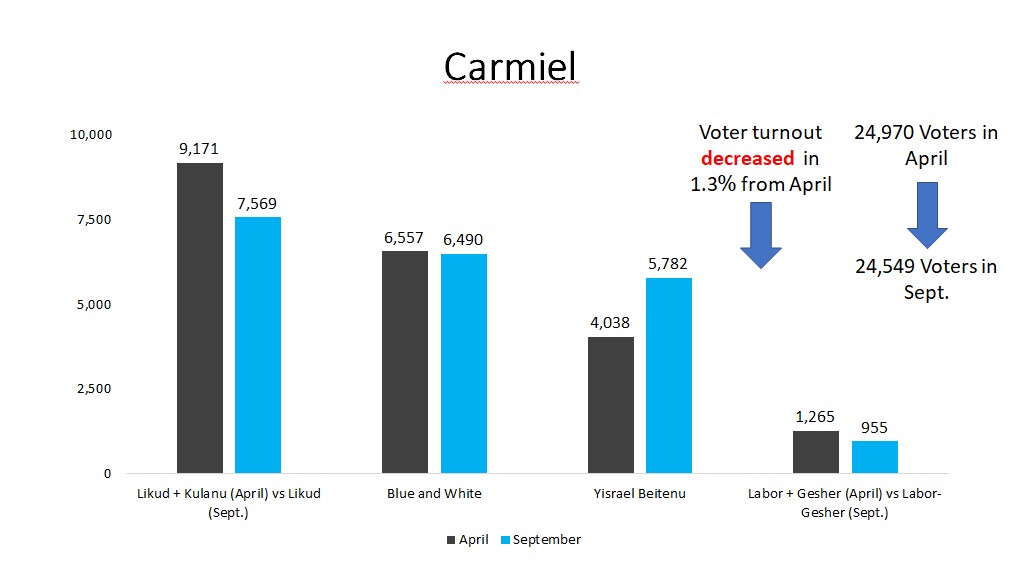

For the parties, where turnout will be strong is even more important than general turnout. As in the United States, geographic location can tell you a lot about people’s voting. Cities and towns, whose residents enjoy higher socioeconomic status, have consistently voted for parties belonging to the center-left bloc. Conversely, Israelis living in ‘development towns and lower to middle class cites such as Karmiel or Bat Yam almost always vote for the Likud or one of its satellite parties. If we take Karmiel as a case study, we can see why the Likud’s representation in the Knesset dropped. While 37% of those who voted in the April election chose Likud, in September this went down to 31%. At the same time, Blue and White’s share of the vote stayed steady at 26%. The real change can be seen in the numbers supporting Liberman’s Yisrael Beitenu party, which rose from 16% to almost 24%. It is important to note that this shift occurred despite the fact it took place after Liberman already made clear that he no longer necessarily sees himself as a member of the traditional center-right bloc.

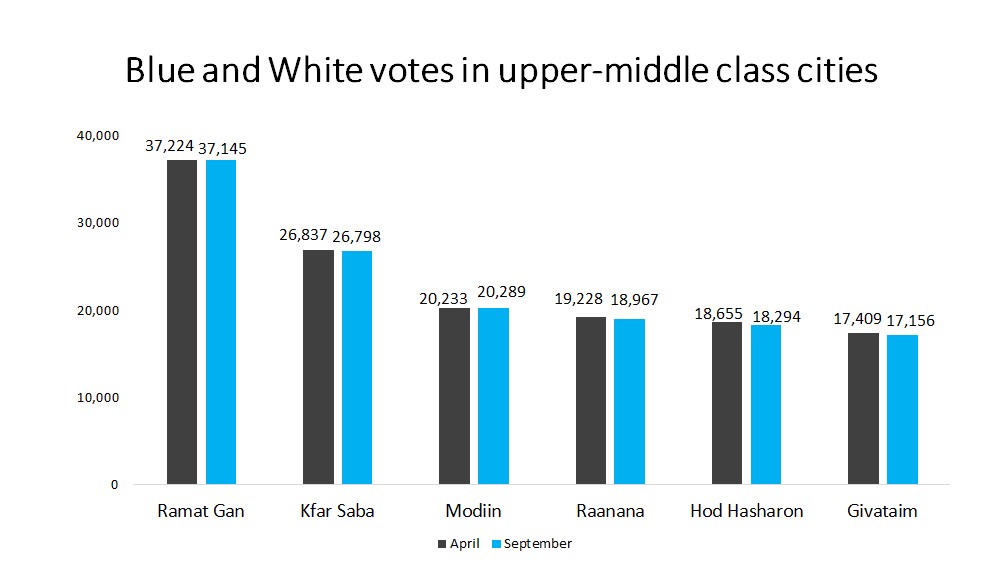

A mirror image of this phenomenon can be found in upper middle-class cities such as Givatayim, Kfar Saba or Ra’anana. In these cities, Blue and White was able to keep its share of the votes, garnering between 40% and 50% in both national elections. More importantly, voter turnout remained steady– or even rose– from April to September. In the Likud strongholds, on the other hand, turnout dropped between the two rounds by 0.4%, and in some cities such as Karmiel, it sank as much as 1.3%.

This is exactly the trend that Netanyahu hopes to reverse in March. He is counting on his base coming out to vote this time. Netanyahu is assuming that while they stayed home in September, now–when they see that the Likud-led government is in danger, and perhaps empathize with his sense that he is being victimized by the so-called elites, traditional Likud voters will come out in droves. Gantz, of course, hopes for the opposite, and is betting that his base will be fired up by Netanyahu’s indictment and the prospect of defeating him for the first time in over a decade.

A Silver Lining?

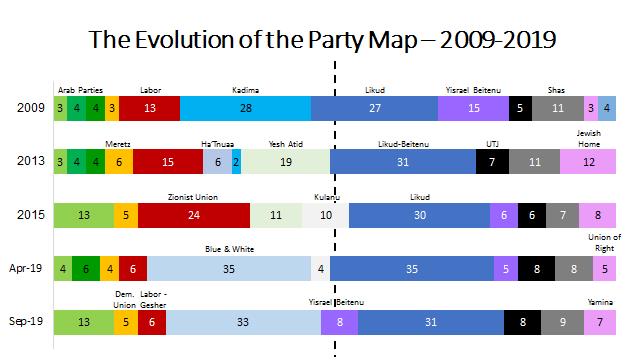

Putting aside the dysfunctional situation whereby the elections have failed to ensure that the vote of the people results in a functioning government, this situation actually has a silver lining. The number of parties which succeeded in crossing the electoral threshold and making it into the Knesset has dropped to nine in September’s election, and is expected to sink even lower in March. This has led to a reality in which over the course of these three elections, we have seen the solidification of two major blocs in Israel’s parliament, with both Likud and Blue and White obtaining a significant number of seats in the Knesset.

This impact of this change on the political system is significant. If the trend continues, we could be inching closer to a reality in which smaller sectorial satellite parties will hold less leverage over the larger parties, thus ensuring that the needs of powerful minorities do not overshadow those of the mainstream Israeli electorate.

Nevertheless, this snapshot of the state of Israeli parties can be deceiving. Many of the slates presented to the Central Elections Committee are actually conglomerations, or what are termed –technical blocs—of parties, that are made up of smaller political movements. This phenomenon is especially prominent on the left of the political map. In 2013, eight center-left lists were elected to the Knesset. In the 23rd Knesset which will be voted into office in March, we expect to see only three parties representing these same voters: Blue and White, Labor-Gesher-Meretz, and the Joint List. These three, however, are actually made up of ten different parties: three in Blue and White, three in Labor-Gesher-Meretz, and four in the Joint List.

It is too early to ascertain the full implications of this new reality. On one hand, we could be at the beginning of a movement in which these unified lists actually become permanent mergers of the smaller parties into larger ones, and an eventual stabilization of the Israeli political system. On the other hand, this trend towards unification may only be temporary. It could very well be that the slates will split after the election and they make it into the Knesset. More problematically, in future elections we could see a further proliferation of these personality-based ‘micro-parties.’

Scenarios

The benefit of this year’s previous two elections is that they provide us with e the most accurate statistics for predicting which parties Israelis can be expected to vote for in the third round in March. While it is true that two or three seats moving from one bloc to the other would alter the outcome of the election disproportionally, we are still facing four basic possible scenarios with regard to the type of government that might be formed.

The first is a center-left government that will significantly alter the country’s approach on both international and domestic policies. Based on the latest polls, this is an unlikely scenario, and could only materialize if Blue & White would take seats from the right, and if the new Labor alliance would significantly outperform its results from the previous two rounds. Then, Benny Gantz would have to convince everyone— from the Joint List to Avigdor Liberman – a very tall order – to join in his coalition, or at the very least– to enable a vote of confidence to enable him to form a government by abstaining in the initial critical vote.

The second, and most likely possibility, is a result similar to what we saw after the September and April’s elections. The question then would be, if this time Blue and White and Likud could agree to form a unity government, perhaps together with a number of other smaller parties. For this to happen, either Netanyahu would need to finally step aside, or Blue and White would need to change its policy on partnering with an indicted prime minster.

In terms of policy, in theory– a unity government could form the platform that would finally take on some of the most pressing issues facing Israeli society. By representing such a broad consensus, it would be able to pass much-needed electoral reform, articulate a grand bargain on matters of religion and state, and finally enact structural and constitutional reforms that government after government have avoided.

In reality, however, the same political compromises that will be necessary to form such a unity government, would likely result in the main partners holding veto power over all decisions, and thus limit its ability to make difficult decisions. Instead, the best that can be hoped for is what I like to call– a desperately needed ‘democratic ceasefire.’ In essence, this would mean a continuation of the foreign and security policies that have been guided by the defense establishment, a responsible stewardship of the economy that would begin to deal with our ballooning deficit, and a freeze on any initiative that would upset the delicate status quo that exists on issues of religion and state. More importantly, a unity government could provide the opportunity for the nation to heal, after eighteen months of bruising partisan wrangling, immunity battles, and savage attacks on the law enforcement agencies.

There is also the option of forming a ‘unity government’ without Netanyahu’s Likud. Since only a simple majority (as opposed to 61 members of Knesset) is needed to establish a functioning minority government, a coalition could be formed including Blue and White, the Labor-Meretz alliance on the left, Liberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu and even parts of Naftali Bennett’s Yamina party on the right. To inaugurate this government the Joint List would need to abstain in the critical vote of confidence. While such a government would enjoy the legitimacy afforded by the support of Zionistic political parties across the political spectrum, it would undoubtedly be criticized from the Right over its reliance on the tacit support of Arab MKs.

Finally, the possibility still exists that the right-wing and religious parties, led by the Likud, will obtain a parliamentary majority of at least 61 seats like they had until a year ago.

As the case against the Prime Minister has progressed and his fight for survival intensifies, it has become even more apparent how in Israel’s system, where there is no constitution, no bill of rights, and legislative and executive branches that essentially operate as one, such a majority could make significant changes that would alter the future of our democracy.

In such a situation, in which the Prime Minister’s primary main interest will be political survival, we can expect to see anti-constitutional initiatives be passed as law, either once they are initiated by the Likud or agreed to in order to placate coalition partners from the more extreme right. This would likely deal a significant blow to the independence of our judicial system, an entrenchment and radicalization of the ultra-Orthodox monopoly’s hold on key levers of power, and most likely– irreversible steps to change reality on the ground in the West Bank.

We must also recognize another painful scenario. If once again, the results are similar to those of the last two elections, and all sides continue to cling to their current positions, there is a real possibility of a fourth national election.

Conclusion

Thinking rationally would lead us to the conclusion that the March election will be the last one of this zany cycle. With no 2020 budget in place, Israel is now operating on 1/12th of the 2019 budget. All reforms and government plans are essentially frozen. And while the security services continue to do their utmost to keep the country safe, Iran is more belligerent than ever, the region is transforming at a dizzying pace, and now the American admiration is adding its peace plan to the mix. This should spur our elected officials to seek the quickest route to governmental stability.

Nevertheless, if the events of the past year have taught us anything, it is that Israel’s democratic system is more broken than we previously imagined. While the civil service remains dedicated, and key institutions such as the judicial system are standing strong under immense pressure, the underlying foundations of our democracy are being eroded. The electoral system is not producing a government and is in dire need of reform; key segments of the Arab and ultra-Orthodox communities are feeling alienated, while the middle class centrists who in the past were regarded as the elites who founded the state, are concerned that religious extremists have an increasingly outsized voice in determining the character of the state. In short, it is becoming more apparent with each passing day, how fragile the constitutional framework of our democracy truly is.

We can only hope that after March 2, whatever the results, political leaders across the spectrum will put their short-term personal interests aside and not only form a government, but actually get to work to implement desperately needed reforms to l safeguard the future of Israel’s democracy.

The article was first published on the Jewish Funders Network.