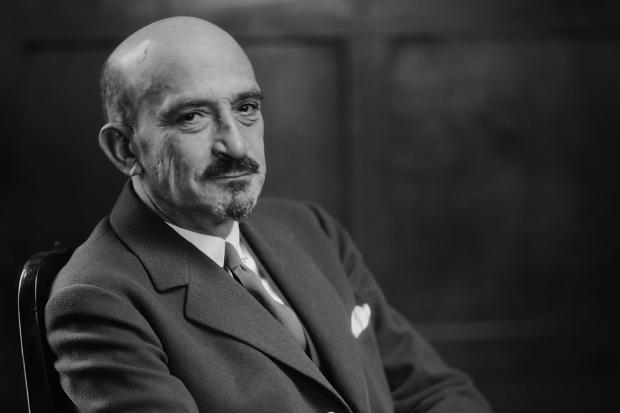

The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann

January 1922 – July 1923

Volume XI, Series A

Introduction: Bernard Wasserstein

General Editor Meyer W. Weisgal, Volume Editor Bernard Wasserstein, Assistant Editor Joel Fishman, Transaction Books, Rutgers University and Israel Universities Press, Jerusalem, 1977

[Reprinted with express permission from the Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel,by the Center for Israel Education www.israeled.org]

The opening of the eleventh volume of the Weizmann Letters, which covers the period from January 1922 to July 1923, finds Weizmann in Berlin on his way back to London from a meeting in Vienna of the Actions Committee of the Zionist Organization. The journey was one of many which Weizmann undertook during this period. Of the nineteen months covered by this volume he spent eleven months outside Britain, an indication of the international nature of the complex diplomatic, political, and financial problems which Weizmann and the Zionist movement faced in these years.

On the diplomatic plane his major preoccupation during the first half of 1922 was the delay of the League of Nations Council in passing the Mandate for Palestine. At the San Remo Conference of April 1920 the Allied Powers had decided to allocate the Mandate for Palestine to Britain. In consequence of this decision a civil administration, headed by Sir Herbert Samuel, had taken office in Palestine in July 1920. However, mainly because of the long delay in the signing of a conclusive peace treaty between Turkey and the Allied Powers, the Mandate itself could not be promulgated immediately. A draft had been prepared by the British Government in 1920 but was not passed by the Council of the League of Nations until July 1922, and it did not formally come into force until September 1923. The intervening period created political uncertainty, since the legal basis of British rule in Palestine remained open to question. Delay in the Mandate’s ratification led to attempts from various quarters to alter its terms, and even to prevent its passage altogether.

The problem was exacerbated by the large number of interests involved. The Vatican professed itself dissatisfied with the provisions of the Mandate regarding the Holy Places and was able to exert considerable influence on Roman Catholic members of the League of Nations. Among these, Italy and France had their own national interests in the Levant which led them to support the Vatican. France, in particular, wished to strengthen her position as the designated Mandatory Power in Syria. The U.S.A., although not a member of the League, was recognized by the British Government as having a locus standi in the matter of the Mandates, and Britain had undertaken not to present the draft for Palestine to the League before receiving American approval. The State Department sought British guarantees regarding the commercial and juridical interests of Americans in Palestine, and this too caused delays. The uncertainty encouraged the opponents of Zionism in both Britain and Palestine to redouble their efforts in the hope of securing the rejection, or at least revision, of the Mandate. A Palestine Arab Delegation had been in London since August 1921 trying to persuade the British Government to abolish the Jewish National Home in Palestine, withdraw the Balfour Declaration, and permit the formation of an Arab government. The Delegation failed in its objective, but it secured some support in England, particularly from some Conservative M.P.s and peers. Moreover, early in 1922 Lord Northcliffe, the powerful owner of the Daily Mail and The Times, visited Palestine and formed a negative view of Zionism—an attitude dutifully echoed in the columns of his papers. All these pressures on the Government formed a dangerous challenge to the Zionist aim of securing the early passage of the Mandate through the League Council in unaltered form.

To thwart this diverse coalition of interests threatening to wreck his policy of reliance on British adherence to the Balfour Declaration, Weizmann succeeded in concerting a many-sided diplomatic campaign. The League Council postponed consideration of the subject from meeting to meeting, and he sometimes despaired of the Mandate’s ever being passed without drastic changes in its text to the disadvantage of the Zionists. After an adverse vote in the House of Lords in June 1922 he wrote pessimistically to David Eder, the political head of the Zionist Executive in Palestine, that if the Zionists were asked to signify their assent to the withdrawal of some of the pro-Zionist provisions of the Mandate they should reply that `nothing further can be conceded. I think we shall be much stronger if we thank the British Government for all its good intentions towards us, and withdraw from the position as we did in the case of Uganda.’ The events between 1903 and 1905 were not, however, repeated, in part at least because of the effectiveness of the pressure applied by the Zionists at nodal points of power around the world.

Weizmann sought to remove Vatican hostility to the Mandate with a personal visit to Rome in March–April 1922. He hoped for an audience with the Pope, but this was not granted. He did, however, meet the Papal Secretary of State, Cardinal Pietro Gasparri; yet, as he wrote, ‘although it was a very friendly and even genial conversation, it left very little doubt in my mind that he is unfriendly.’ Weizmann’s visit appears to have confirmed the Vatican’s suspicions of Zionism, but he was not daunted, and he had meetings with senior Italian politicians and the King of Italy. He induced local Zionists to lobby the Foreign Minister and arranged public meetings in favor of the Mandate so that favorable opinion was generated in the Italian Chamber of Deputies.

Similar attention was given to other Catholic Powers: a special representative was sent to Spain; French newspapers were encouraged to support the Zionist cause; Brazil was persuaded to support the passage of the Mandate after a telegram had been dispatched (at Weizmann’s request) to the Brazilian President by Lionel de Rothschild (whose bank’s voice carried significance in Brazil).

The U.S.A. had to be dealt with at long distance, since Weizmann had cancelled his plan to visit America in the winter of 1921-22. A Zionist delegation, including Nahum Sokolow and Vladimir Jabotinsky, was, however, already there and it succeeded in organizing American opinion in favor of the Mandate. Although both President Harding and the Department of State were cool towards Zionism, a major step towards removal of the American obstacle was taken when both Houses of Congress passed resolutions in favor of the draft. The political importance of these resolutions was all the greater because they were sponsored by the generally isolationist Senator Henry Cabot Lodge and Representative Hamilton Fish. After this, American hostility to the Mandate evaporated.

Weizmann was able to play a much more immediate role in overcoming domestic British opposition to the Mandate and to the Jewish National Home. The Zionists were fortunate in having the predominant weight of ministerial opinion (the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, the Colonial Secretary, Winston Churchill, and the Lord President of the Council, A. J. Balfour) on their side. Sir Alfred Mond, the Minister of Health, who had travelled to Palestine with the Zionist leader a year earlier, and who was a convinced supporter of the cause, worked closely with Weizmann and helped discreetly to influence Cabinet opinion. However, Weizmann was concerned by the apparent propensity of Sir Herbert Samuel, the High Commissioner in Palestine, and of some Colonial Office officials, to accord weight to Palestine Arab nationalist views, and by the impact of the Arab Delegation in London on some sections of public opinion. He was disturbed also by the continued opposition to Zionism among sections of the assimilated Anglo-Jewish gentry, and of ultra-Orthodox Jewish organizations (especially the Agudas iisroel), with their representations against the Mandate to the League and to the British Government. In a letter to Albert Einstein he wrote:

‘All the shady characters of the world are at work against us. Rich servile Jews, dark fanatic Jewish obscurantists, in combination with the Vatican, with Arab assassins, English imperialist antisemitic reactionaries—in short, all the dogs are howling.’

Weizmann’s correspondence reflects his diversified efforts to keep British political opinion favorable to Zionism. Besides direct meetings with British ministers and officials, he employed all the techniques open to a pressure group that was both domestic and international in character. General Smuts, an old Zionist enthusiast, and one of the architects of the Mandate system, issued a pronouncement favoring the Palestine Mandate. Balfour was lobbied at the British Embassy in Washington, and he made a statement reaffirming Britain’s intention to secure passage of the Mandate and uphold the Balfour Declaration policy. Jewish organizations in Palestine cabled the Colonial Office insistently. All this had a certain effect. Less productive was Weizmann’s attempt to mollify Lord Northcliffe. At Weizmann’s instructions special efforts had been made in Palestine to impress him during his visit there; he remained unimpressed. On his return to England Northcliffe gave the Zionist leader five minutes to state his case, stationing a man nearby with a stop-watch to shout when his time was up (R. Pound & G. Harmsworth, Northcliffe, London, 1959, p. 846). Northcliffe’s newspapers continued their anti-Zionist campaign, which ceased, however, with the magnate’s early death.

Old friends of Weizmann again proved helpful to him in this critical period. C.P. Scott, editor of the influential Manchester Guardian, undertook to speak up on behalf of the Zionists at one of his regular meetings with Lloyd George; this paved the way for two interviews between Weizmann and the Prime Minister in April and May. Parliamentary opinion was mobilized by William Ormsby-Gore, who had served as Political Officer accompanying the Zionist Commission to Palestine (headed by Weizmann) in 1918, and who had been fired by the Zionist ideal.

Weizmann spent these months arguing the case for the Mandate almost incessantly—and as usual he acted with an instinct for the true locations of power and opinion formation in the British political establishment. The letters in this volume show him meeting the International Affairs Committee of the Labour Party, speaking in Oxford Town Hall, rebuking the editors of the Westminster Gazette and The Times, visiting Sir Oswald Mosley (at that time a rising star among Tory backbenchers), all this in addition to his frequent interviews with ministers and officials. But the letters reveal only the tip of the iceberg.

Weizmann’s discreet but persistent negotiating in this period recalls the ‘thousand cups of tea’ he had consumed in the drawing rooms of England prior to the Balfour Declaration. His appointments diary for 1922 (which survives in the Weizmann Archives in Rehovoth) notes lunches at the Ritz or the Carlton Grill, dinners at the House of Commons, or visits to the Travellers’ or the Cavalry Club with a diverse cross-section of British ‘society.’ Among his interlocutors we find Dean Inge, T.E. Lawrence, Lionel Curtis, Richard Meinertzhagen, Ronald Storrs, Josiah Wedgwood, Lord Eustace Percy, General Sir George Macdonogh, Earl Winterton, and—perhaps most significant of all, as a pointer to Weizmann’s enduring link with the inner political establishment—Frances Stevenson, the Prime Minister’s secretary and future wife.

This activity brought its reward. On 4 July 1922 the House of Commons, after a debate on Palestine, reversed the earlier resolution of the House of Lords, and emphatically endorsed the Mandate and the pro-Zionist policy of the Government. And, at last, on 24 July, the Council of the League of Nations, gathered in London, unanimously ratified the Mandate as submitted by Britain.

The previous seven months of procrastination had placed an enormous strain on Weizmann, who was in any case by nature an impatient rather than a phlegmatic man. In a letter to his family in Palestine he poured out his feelings:

‘It’s difficult to describe the sorrows and aggravations I have had to endure from all sides in the course of the last six months; at times it looked as if all the hard work of so many sorrowful years was in very grave danger and, God forbid, almost near collapse: days of distress, sleepless nights and endless traveling without a single moment’s peace. So, difficult and bitter weeks and months flew by; the last month was perhaps the worst of them all.’

Writing to his sister Miriam, just as the League Council was holding its crucial final session, Weizmann declared:

‘You are right—the Mandate was written for the greater part with my own blood, but who knows, perhaps this is the purpose of my wandering all my life, from Motele to London, in order to accomplish this great task; when I look at the Jewish community here, and in all the Western countries, when I remember the destruction in the East, my heart freezes, and I come to the conclusion that only the Chosen Ones who have acquired all their moral strength from the only true Jewish source—only they are prepared and fit to assume the burden of work for the sake of others, and they will succeed in reviving the dry bones.’

This demonstrates not merely Weizmann’s occasional propensity to self-dramatization but, more significantly, the overwhelming importance he attached to the Mandate—an importance perhaps even greater than that of the Balfour Declaration. The Mandate was a legal as well as a political document, international in nature, specific rather than a statement of general intention, and a document which incorporated and expanded the Balfour Declaration’s recognition of the Zionist Organization as the legitimate representative of the Jewish people.

With the Mandate finally approved, Weizmann was able-to turn his attention to the more difficult long-term problems of building on the foundation that had been created, of translating the Jewish National Home into reality. During the remaining year covered by this volume we observe Weizmann’s energies absorbed in the more mundane tasks which were to engage him for the rest of the decade—beating off opposition to his policy and leadership from within the Zionist movement, wrestling with the increasingly desperate financial situation of the Zionist Organization, dealing with the Arab opposition to Zionism, and maintaining the stability of the political relationship that had been constructed between the Zionists and the British Mandatory government.

The tremendous drain on Weizmann’s physical and mental resources in the months prior to the passing of the Mandate was taking its toll. Writing to his close friend Sir Wyndham Deedes (Chief Secretary of the Government of Palestine), he declared that he had decided to resign and that he would not accept the Presidency of the Zionist Organization again, even if he were elected by the Zionist Congress. Instead he would devote himself to the building of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. have had more than my share of politics, which I heartily detest.’(Deedes himself felt a similar detestation, and was anxious to resign his position in Palestine and take up religious and social work in London; he remained in Palestine for a further year only as a result of the vigorous urging of Weizmann and Samuel.) Weizmann’s determination to withdraw from the Zionist leadership was strengthened by attacks to which he was subjected from within the movement.

Early in 1922 a group of pre-war antagonists of Weizmann, the Dutch banker Jacobus Kann, Max Nordau, Jean Fischer, and Alexander Marmorek (two of them members of the former Smaller Actions Committee), engaged in fierce opposition to what they held to be the wasteful and unbusinesslike manner in which the Zionist Organization was being administered. Rejecting these criticisms, Weizmann issued a challenge to his opponents:

‘It may be that I am mistaken. I did not receive my wisdom on Sinai. If you have been at it for eight years as I have it is possible to suffer from aberrations. As far as I am concerned, and I think I can say the same for many of my friends, we shall be glad to leave you and your friends the responsibility. As far as I am concerned, I can say this with certainty. […] A Congress should then be convoked in the summer, and its only task will be to elect a new, an entirely new leadership, and naturally also to map out new paths. Please make ready to offer the candidates. […] The present Executive has been given nothing for the road but an empty sack to go `schnorring, and a great deal of abuse. I wish the next leadership an easier life.’

This was no mere rhetorical threat: Weizmann repeated his determination to resign a few days later to a confidant, I.A. Naiditch: `The work has become unbearable for me […] the demoralization, the undermining of everything […] has deprived me of the last vestiges of my strength. I cannot and will not work any more.’

He did not resign. He soldiered on in spite of the internal dissension that persisted after the passage of the Mandate. At the Annual Conference of the Zionist Organization in August 1922, Weizmann’s policy of co-operation with, and reliance on, the British came under severe attack from both left and right wings of the movement, and simultaneously from an opposition group, headed by Jabotinsky and Menahem Ussishkin, within the Executive. Weizmann was incensed:

‘It is impossible to work with them under these conditions; working without them would mean creating an opposition along the whole line at the very beginning—what an impasse! I don’t know whether this will be settled and whether God will give me enough strength to have the willpower to leave now, once and for all! My heart is very heavy!’

An uneasy peace was patched up at the conference, and threats of resignation from all sides were withdrawn. But the animosity between Weizmann’s supporters and his opponents continued to simmer. It was clear that the final schism had been delayed but not averted.

In November 1922 Weizmann once again reached a definite decision to resign, a decision which he foresaw ‘no possibility of altering.’ However, at a meeting of the Actions Committee of the Zionist Nov. Organization in January 1923, it transpired that it was Jabotinsky who submitted his resignation. Nevertheless Weizmann soon wrote yet again that he had ‘irrevocably decided’ to resign the summer of 1923. But another letter written at about the same time to one of his closest political adjutants, Colonel F.H. Kisch, makes it clear that this was not irrevocable: his resignation would largely depend on whether the Congress would be prepared to make ‘a great many changes in the Executive.’ Before leaving for the U.S.A. in February 1923 he sought Sokolow’s support: ‘If we stand together it may be possible to resolve the crisis. If we fall out, I shall leave.’ Relations between the two leaders remained cool, but at the Congress of August 1923 (with which Volume XII of the Weizmann Letters opens) Weizmann succeeded in securing a renewed mandate for his policy, with an Executive composed, in the main, of men much closer to his views.

Weizmann’s family life during this period was an additional source of anxiety. His incessant travels separated him from his wife and children. His income from his patented chemical processes had now reached a high level, and he was able to provide some assistance for his mother, brothers and sisters in Palestine who were then in financial straits. He tried, without great success, to secure employment for his brothers there. Weizmann felt deeply responsible for his family, and, as he told Naiditch, ‘all this is oppressing me, choking and exhausting my last ounce of strength. I must be a free man.’

Weizmann had hoped that the passage of the Mandate would guarantee the political, and thereby financial, stability of the National Home. These hopes were dashed. And, so long as the finances of the Zionist Organization remained inadequate, and the attitude towards Zionism of the British Government uncertain, Weizmann considered that it would be an act of irresponsibility for him to withdraw from the fray.

The acute financial plight of the Zionist Organization provided easy ammunition for Weizmann’s internal critics, and lay at the root of the failure fully to capitalize on the political triumphs of the years 1917-22. He was ready to ascribe the Zionist inability to raise the large sums required for the National Home primarily to the doubts arising from non-approval of the Mandate. It is noteworthy that one of his first acts immediately following its achievement, in July 1922, was the proclamation of a fund-raising campaign. But the passage of the Mandate did not solve the financial problems. Indeed, it tended to render them even more acute by increasing the burden of expenditure weighing on the Zionist institutions in Palestine. In November 1922 Weizmann travelled to Palestine to examine the situation for himself. He was shocked by what he found. He outlined the position in a letter to his wife:

‘The general mood among the Jews is sombre and angry, the main reason being—lack of money. During the last two months, the amount of 40,000 pounds was received here, of which £10,000 was donated by one Jew, £8,000 was lent by the bank, which means that the K [eren] H[ayesod] gave only £22,000 in two months. Of course, this situation is impossible; teachers haven’t been paid, clerks haven’t been paid either—everyone is angry and upset. Moreover, there is a general economic crisis in the country, just like everywhere else. Unless drastic measures are taken, economies on the one hand, and more intensive collecting on the other, everything will stop, and the success achieved during the last two years will be wiped off the face of the earth.’

After two further weeks in Palestine his concern deepened, and he warned Sokolow that there was a ‘danger of complete collapse here,’ the entire Jewish National Home being ‘a millimetre from disaster.’ There was nothing left for the Zionist movement to consider save `either how to liquidate everything with honour, or how to obtain money.’

This desperate shortage of funds induced Weizmann to undertake, almost immediately after his return to London from Palestine, a grueling four-month journey to the U.S.A., his second visit in two years. The main purpose was to raise cash for the Keren Hayesod. A total of £300,000 (plus a further £200,000 in pledges) was subscribed: less than the more extravagant expectations which Weizmann had entertained, but a solid achievement nevertheless, helping the Zionist institutions in Palestine over a period of extreme difficulty, and staving off the bankruptcy which threatened the movement.

The journey had an important secondary purpose: to heal the wounds inflicted on Zionism in the U.S.A. (and on its fund-raising capabilities) by the split of 1921 between the followers of Weizmann and those of Justice Louis D. Brandeis. Weizmann had no intention of courting opponents who had seceded from active participation in the movement and were now trying to establish, in rivalry as it were to the Keren Hayesod, an organization for investment in Palestine, the Palestine Development Council. Instead he endeavored to attract others of the wealthy American Jewish leadership, hitherto standing aloof. His most notable success was with Louis Marshall; the warm relationship which he established with Marshall laid the basis for the latter’s participation in, and acceptance of, the chairmanship of the enlarged Jewish Agency which was eventually convened in 1929.

Such an Agency, incorporating representatives of both Zionist and non-Zionist elements in world Jewry, was presaged in Article Four of the Mandate. Weizmann believed it to be vital, for both political and economic reasons, to incorporate within its framework those who, while not prepared to subscribe to the political goals of

Zionism, would support its economic, settlement and development activities. Besides Marshall in the U.S.A., Baron Edmond de Rothschild in France was a likely candidate for such a role. In England, he had already persuaded Sir Alfred Mond to head an `Economic Council,’ for this purpose. There was, of course, an inherent tension between this type of body and the Zionist Organization. Weizmann regarded the support of such men as crucial, though the generic term which he repeatedly employs to identify them in these letters is, significantly, ‘the others.’

A by-product of these efforts was the progress made in the foundation of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. This had been Weizmann’s cherished project for two decades. In 1918 he had laid the foundation stones of the university on Mount Scopus, while Turkish guns could still be heard on the front a few miles to the north. The formal opening of the university would await 1925, but thanks to donations from, among others, Baron Edmond de Rothschild, Elly S. Kadoorie, and Felix Warburg, a start was made with a chemical laboratory, designed as a nucleus for the medical faculty of the university which was to be established with the support of the American Jewish Physicians’ Committee. To signify that the university had actually begun work, the inaugural lecture was delivered in Jerusalem early in 1923 by one of the university’s most noted protagonists—Albert Einstein.

Above the foundations now being laid in Palestine there continued to loom the overriding political problem threatening the entire Zionist enterprise—Arab opposition. The period covered by this volume was of decisive importance in the development of the Arab-Jewish conflict, and illustrates Weizmann’s characteristic approach to its solution. During 1922 and 1923 the political structure of Mandatory Palestine crystalized in a form which was to remain essentially unaltered until the late 1930s. Notwithstanding British efforts to incorporate the Arabs of Palestine within the political community, they remained fundamentally alienated from the Mandatory regime and hostile to the Jewish National Home. Although the Zionists did not consider their enterprise to be in any way dependent on Arab acquiescence, Weizmann attached great weight to some form of Zionist-Arab agreement, as did indeed the British Government.

In November 1921 Weizmann had participated in discussions in London with Riad as-Sulh, a Lebanese former minister in the Damascus government of Emir Faisal. These talks were followed by a series of meetings in Cairo between Zionist representatives and a group of Syrian politicians in exile. Weizmann strongly approved of these negotiations, but urged that any agreement ‘must emphasize our priority [in] Palestine.’ Several Zionists and British officials expressed reservations as to the credentials of the Arab participants (none of whom was a Palestinian) and to their sincerity. But Weizmann’s initial view was that the talks should go on: it does not matter even if this group is not fully representative and if they are suspicious. All Arabs are suspicious, and no group is representative.’

It gradually became clear that the Arab representatives’ real interest in the talks was to drive a wedge between British and French in the Middle East, and to secure support for an Arab regime in place of the French Mandatory authority in Syria. Clearly, the countenancing of any such proposal would endanger the entire position built up by the Zionists over the previous five years. The talks therefore reached no conclusion. In the course of 1922 further discussions took place (again with Weizmann’s active encouragement) between Zionist spokesmen and other (non-Palestinian) Arabs, most notably Prince Habib Lotfallah (a Syrian resident in Egypt) and the Emir Abdullah of Transjordan. Writing to Chaim Kalvarisky, one of the Zionist participants, Weizmann declared:

‘We cannot sacrifice (a) the Mandate, (b) immigration, and above all (c), which is very important, we remain loyal to England and France, and nothing can go into our pact with these gentlemen that could be interpreted or considered as a hostile gesture towards England or France. In my opinion, these are the fundamental principles to which we should adhere while trying to arrive at a basis of understanding with these gentlemen in the economic domain, collaboration in business, and the intellectual sphere if possible. And it is still necessary to be absolutely certain that the Palestinian Arabs participate in the negotiations. The Arabs of other countries are only of secondary value.’

Whereas the Zionists regarded agreement with the Arabs as necessary and desirable, though not a precondition, for the successful implementation of Zionism, the British, and most notably the High Commissioner in Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel, laid primary stress on securing some form of Palestinian Arab acquiescence to the Jewish National Home. After the passage of the Mandate, therefore, the Palestine Government and the Colonial Office in London continued their efforts to draw the Arabs into the Mandatory political community. Samuel (who was the architect of this policy) hoped that Arab fears of Zionism could be allayed by a new, moderate interpretation of the Balfour Declaration policy, and by the establishment of a constitutional form of government giving the Arabs a voice in deciding the future of the country.

The first step towards this goal was the publication in June 1922 of a White Paper (formal policy statement) drafted by Samuel. This document formed the basis of British policy in Palestine for nearly a decade. It emphasized with careful balance the continuing British commitment to support Zionism while seeking to reassure the Arabs of Palestine as to the implications of that support. It was stressed that the British Government had never

‘at any time contemplated, as appears to be feared by the Arab Delegation, the disappearance or the subordination of the Arab population, language or culture in Palestine. They would draw attention to the fact that the terms of the [Balfour] Declaration […] do not contemplate that Palestine as a whole should be converted into a Jewish National Home, but that such a Home should be founded in Palestine […] It is also necessary to point out that the Zionist Commission in Palestine […] has not desired to possess, and does not possess, any share in the general administration of the country.’

While not specifically precluding the eventual establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, the White Paper certainly did not prescribe such an outcome:

‘When it is asked what is meant by the development of the Jewish National Home in Palestine, it may be answered that it is not the imposition of a Jewish nationality upon the inhabitants of Palestine as a whole, but the further development of the existing Jewish community, with the assistance of Jews in other parts of the world, in order that it may become a centre in which the Jewish people as a whole may take, on grounds of religion and race, an interest and a pride. But, in order that this community should have the best prospect of free development and provide a full opportunity for the Jewish people to display its capacities, it is essential that it should know that it is in Palestine as of right and not on sufferance. That is the reason why it is necessary that the existence of a Jewish National Home in Palestine should be internationally guaranteed, and that it should be formally recognised to rest upon ancient historic connection […] This, then, is the interpretation which His Majesty’s Government place upon the Declaration of 1917; and, so understood, the Secretary of State is of opinion that it does not contain or imply anything which need cause either alarm to the Arab population of Palestine or disappointment to the Jews.’

The White Paper had been drawn up by Samuel after meetings with the Zionists and the Palestine Arab Delegation at the Colonial Office, and it was specified that the policy would be implemented whether they assented or not. The White Paper (as well as the Mandate itself) was rejected by the fifth Palestine Arab Congress which met at Nablus in August 1922. The Zionists, on the other hand, undertook ‘that the activities of the Zionist Organization will be conducted in conformity with the policy’ of the White Paper. Privately, however, Weizmann was disappointed. He regarded the policy as one ‘which will no doubt be interpreted by the Jewish World as a whittling down of the Balfour Declaration,’ and he informed Deedes that although the Zionists would loyally abide by the White Paper policy, they could admit of no further concessions to Arabs demands.

The publication of the White Paper and the passage of the Mandate were followed in August 1922 by the promulgation as an `Order-in-Council’ of a constitution for Palestine which had been drafted in the course of the previous year. The most important element in this constitution was its provision for a Legislative Council, of which a majority of the members was to be elected (the minority being officials of the Government of Palestine). The council was to be so formed that there would be at least two Jewish elected members, in consequence of which the Arab elected members would not, by themselves, form a majority. The council was to consider all legislation, but it could pass nothing in any way repugnant to or inconsistent with the Mandate. The Arab nationalists in Palestine rejected the whole idea; the Government of Palestine decided to ignore their opposition and proceed with the elections to the proposed council. When they were held in February 1923, these elections were boycotted by almost the entire Arab population: in fact, only 1,397 votes were cast altogether, and of these 1,172 were Jewish. After this fiasco, the Government had little choice save to abandon, for the time being, the proposed Legislative Council. Instead, Samuel attempted to achieve the same aim, that of integrating the Arabs of Palestine within the Mandatory polity, by appointing instead an ‘Advisory Council’ with the participation of leading Arab notables. Such a council had, in fact, existed in Palestine from 1920 to 1922, but had been terminated in anticipation of the Legislative Council. At first, it seemed that this solution might work, but in the summer of 1923 the Arab nominees to the council withdrew, and that project too had to be abandoned.

These exercises in constitution-making on the part of Samuel and the Mandatory government heightened tensions between the yishuv (the Jewish community in Palestine) and the British, and between the yishuv and Weizmann himself. These tensions were not new; indeed, they were inherent in the situation, and had existed from the outset of the British occupation of Palestine, and had long concerned Weizmann. The situation now decided him to enlist Colonel F.H. Kisch, an Anglo-Jewish officer born in India, who had participated as a military expert in the Paris Peace Conference, to take charge of Zionist political work in Palestine. This was a matter of some urgency, since Dr. David Eder, who had previously filled this role, wished to return to his medical practice in London, and Weizmann was anxious that Ussishkin, the so-called ‘strong-man’ of Russian Zionism, should not further exacerbate the delicate relations between the Zionists and the British. Kisch assumed the post of `Director of the Political Department of the Palestine Zionist Executive’ at the end of 1922. In 1923 he was elected its Chairman by the Zionist Congress, Ussishkin being side-stepped into the leadership of the Jewish National Fund. Kisch, who was both a pukka sahib and a staunch Zionist, proved an ideal choice for the position—in effect that of Weizmann’s ambassador both to the yishuv and to the Mandatory government—and he remained in office in Jerusalem until 1931.

The collapse of Lloyd George’s coalition government in October 1922 had occasioned Weizmann some worry lest the new Conservative administration, headed by Bonar Law and including some noted opponents of Zionism, reverse its predecessor’s policy in Palestine. These anxieties came to a head in the summer of 1923 when a Cabinet committee was set up to consider the entire question anew, and reports (leaked to the Zionists by Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen, Military Adviser to the Colonial Office), suggested that the committee might pronounce against Zionism. Weizmann, who was holidaying on the Continent in preparation for the forthcoming Zionist Congress, was hastily summoned back to London by the Zionist Executive in order to make representations to the Government. He had meetings with Balfour and the Duke of Devonshire (the new Colonial Secretary), and wrote to the Colonial Office protesting against any further reformulation or re-adjustment of British policy as ‘a shattering blow which might well prove fatal.’ Weizmann’s fears proved groundless. The Cabinet Committee’s report, drafted by the Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, recommended no drastic change in policy. The one new proposal made by the committee—the establishment of an Arab Agency on a par with the Jewish Agency—was rejected by the Arabs in October 1923.

This volume closes at the end of July 1923 on the eve of the opening of the XIIIth Zionist Congress at Carlsbad. The Congress afforded an opportunity for the expression of strong criticism of both Weizmann and the British Government. But Weizmann was able to defend his record with an account of the solid achievements of the previous two years. The change of government had brought no change in policy. The Mandate, passed by the Council of the League of Nations, and accepted as international law, remained intact. The finances of the Zionist Organization, although still precarious, were not as desperate as in 1921-22. Preliminary steps had been taken towards the formation of a Jewish Agency for Palestine incorporating non-Zionist Jewish elements. Immigration to Palestine was proceeding steadily at the rate of eight thousand a year. The nucleus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem had been established.

If the essential conflict of interests between Arabs and Jews in Palestine remained unresolved, there had at least been no recrudescence of the anti-Jewish riots of 1920 and 1921. The Jewish National Home was as yet still a blue-print rather than a concrete reality; but it was no longer merely a utopian vision. Zionism, under Weizmann’s leadership, had reached the end of the beginning.

BERNARD WASSERSTEIN