The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann

March 1926– July 1929

Volume XIII, Series A

Introduction: Pinchas Ofer

General Editor Barnet Litvinoff, Volume Editor Pinhas Ofer, Transaction Books, Rutgers University and Israel Universities Press, Jerusalem, 1978

[Reprinted with express permission from the Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel,by the Center for Israel Education www.israeled.org]

Volume XIII of the Letters of Chaim Weizmann, covering the period March 1926 to July 1929, gives preponderance to two crucial issues: the economic crisis which struck at the Jewish community in Palestine, bringing the Zionist Organization to the verge of bankruptcy and threatening the very survival of the Jewish National Home; and the resumption of efforts to form an expanded Jewish Agency with the participation of non-Zionist Jewish leaders.

In March 1926 Dr. Weizmann and his wife Vera arrived in Palestine to find great distress resulting from the developing economic crisis there. Jewish unemployment had risen from some 1,000 in the early winter of 1925 to 5,000 in the spring of 1926 (and was to reach a peak of 8,440 registered unemployed in August 1927). Many persons not of the working class had no means of livelihood. Emigration ensued, and in 1926 7,365 Jews left Palestine while 13,081 entered. In 1927 Jewish emigration exceeded immigration; 5,071 left the country, against only 2,713 arrivals. This produced grave political as well as economic repercussions upon the Zionist endeavor. The labour situation in Palestine became the dominant factor in relations between the Zionist Executive and the Palestine Government (11 May 1926). The latter adopted the attitude that unemployed Jewish workers were a part of the general population, for whose welfare the Government was responsible, and was therefore prepared, within certain limits, to assist in the relief of unemployment by constructive works. But the consequent expenditure involved affected its attitude towards Jewish immigration, and resulted in the imposition of severe restrictions. Moreover, Lord Plumer, as High Commissioner for Palestine, was led to conclude that ‘the so-called “crisis” is no mere passing phase but represents a permanent condition due to the presence in the country of a population surplus to its present economic capacity,’ and therefore, ‘there is only one practical remedy and that is to further by every possible means emigration from Palestine of the surplus Jewish population.’

To Weizmann such a proposition was appalling. ‘I shall certainly not be a party to any policy which may have as its consequence a re-emigration of Jews from Palestine,’ he wrote, ‘and if the Government forces such a policy on us I shall resign without the slightest hesitation […] Nothing must be done in Palestine which may give a handle to the Government to inflict a policy of that kind upon us.’ On the contrary, urgent steps had to be taken by the Zionist Organization, not only to alleviate the plight of the unemployed, but also to restore confidence to the Jewish people and the British Government in the feasibility of the Jewish National Home. To attain this end, great effort and sacrifice were demanded of Jews everywhere, especially in the United States. In particular, it was up to the Zionist leadership to make an outstanding effort. ‘Worrying about money with which to check the unemployment in Palestine is what keeps me busiest of all,’ Weizmann wrote to a friend.

With the growing distress of the workers, it was decided in the spring of 1926 to provide the unemployed with direct unemployment relief (the dole). The step was taken most reluctantly, not only on grounds of the workers’ morale, but because it dragged the Zionist Organization into financial expenditures that placed a heavy strain on the limited budget available for its activities in Palestine: `I am sorry to have to inform you,’ Weizmann wrote, ‘that the position in Palestine has reached such a stage that […] the Zionist Executive in Palestine—and therefore the whole of the Zionist Movement—will find itself in the Bankruptcy Court. You can judge for yourself the effects of this, which would mean a complete collapse of all we have achieved in the past eight years. I am not an alarmist by nature and have a large dose of optimism, but it is my duty to tell you that the ship is sinking.’

The realization came quickly that the true remedy to the situation would be through implementation of constructive projects which would both provide employment and contribute to the upbuilding of the country. For this purpose it was essential that the Government co-operate with the Zionist Executive, and negotiations were accordingly initiated both in Jerusalem and London. At these negotiations the Government was not asked to make any direct contribution from public funds towards the maintenance of the unemployed, but rather to take a series of effective measures with a view to stimulating the demand for labor by the early execution of essential public works. These requests of the Zionist Executive were eventually granted by the Government. Yet most of the burden had still to be borne by the Zionist Organization.

In August 1927, when the number of unemployed reached its peak, the Zionist Executive decided on a scheme involving building works, road construction, irrigation and land amelioration. Great financial and technical effort was entailed; and generous contributions from some wealthy Jews, for the attainment of which Weizrnann’s efforts were instrumental, paved the way to its successful execution. In April 1928 it was possible to discontinue the dole. This news was communicated to Weizmann while he was in America and was received by him as a most welcome Passover message. Nevertheless the financial situation of the Zionist Organization, exemplified by its difficulties in coping with the unemployment and economic crisis in Palestine, worsened. There was a steep decline in income from Zionist fund-raising, with contributions lagging far behind estimates and commitments.

In addition, demands were made of the Keren Hayesod and Jewish National Fund—out of their limited resources—to rescue two institutions, the American Zion Commonwealth and the Haifa Bay Co., whose financial difficulties threatened to harm the reputation of the Zionist Movement and halt the acquisition of lands in the Haifa Bay area. In these circumstances the Zionist Organization found itself compelled to adopt restrictive measures affecting its most precious sphere of activity, namely, land settlement. Thus the 15th Zionist Congress resolved, in the summer of 1927, that ‘the near future should be devoted chiefly to strengthening and consolidating existing settlements,’ and that no new settlements should be founded `so long as the financial position cannot ensure the possibility of providing such settlements with both land and full equipment during a specified period determined in advance.’

Consistent shortage of money meant that the Zionist Organization had to carry out its activities from hand to mouth, making long-range planning hardly possible. A drastic change was required. Weizmann set himself the task of securing the means to establish the Jewish National Home on solid and lasting foundations. In October 1926, he convened, together with Herbert Samuel, an Economic Conference in London, with the purpose of dealing with the financial aspects of building the Jewish National Home in Palestine, and to advise the Zionist Organization in the realization of its tasks in this sphere. The function of the Economic Conference, which was attended by eminent experts from various countries, was to examine the adequacy of the Organization’s resources and financial institutions for the manifold tasks necessary for agricultural colonization and industrial development, and to formulate proposals whereby those resources could be appropriately increased or supplemented. The Midland Bank in London was approached by Weizmann for a long term loan of £400,000 for Keren Hayesod. Such a loan, it was hoped, would lead to an undertaking on the part of the American Zionists to raise an additional £600,000 and would consolidate all the Zionist institutions and put the Organization on a ‘bearable’ financial footing. This effort, however, failed. Lengthy negotiations, in which Weizmann took a most active part, for another loan in the amount of $3,250,000 for the Jewish National Fund had been conducted with New York bankers, but similarly without result, chiefly owing to disagreement between the Zionist Executive and the Funds on the application-and terms of the loan.

Pursuing another avenue, Weizmann appealed to the British Government to take the initiative in guaranteeing a loan of £2,000,000 to be granted to the Zionist Organization through the League of Nations. He had the sympathy of influential members of the Cabinet in this, but again the scheme came to nothing, for there was reluctance on the part of other members of the Cabinet to assume such an undertaking. In the event, Weizmann was informed that the Foreign Secretary, Sir Austen Chamberlain, had made inquiries in Geneva about the proposed loan and received an unfavorable response. In the race against time, the Zionist Organization was losing. ‘It seems a terrible tragedy that at the time when the development of Palestine offers the greatest possible prospects,’ said Weizmann, ‘we must stand helpless watching the prospects without being able to utilise them for the National Home […] If all these things materialise, and I have no doubt that they will, the face of Palestine will be completely changed in the next three years. Have we enough strength and courage left to utilise all these changes in the interest of the National Home? I am doing my best here to watch these things and prepare for them, but I feel that I am almost alone in the whole Zionist Movement worrying about these matters.’

The best possible prospects for the development of Palestine, as envisaged by Weizmann, were not only connected with large-scale projects to be initiated by Great Britain in the area, but were also a result of auspicious political conditions. The country had been tranquil for a long time, and the three years of Lord Plumer’s tenure as High Commissioner (1925-28) in particular were unmarked by any dramatic incident. Relations between Jews and Arabs seemed to be improving (despite the Wailing Wall incident of the Day of Atonement, 1928, and its repercussions), as Sir John

Chancellor, the High Commissioner from 1928, stated to the Permanent Mandates Commission a few brief weeks before the disturbances of August 1929. In England the attitude towards Zionism seemed also to be improving, and such opposition as had existed towards the Mandate policy was being dispelled. The official Zionist leadership saw as its task the need to strengthen cooperation with Great Britain.

As to relations with the Palestine Administration, problems and disagreements certainly existed, for example, concerning the Beisan Jiftlik lands and the granting of the Dead Sea concession to the Novomeysky group, but these were viewed as friendly differences of opinion rather than as a clash between conflicting policies. Weizmann phrased this attitude as follows: ‘We feel justified in asking for more active support from the Mandatory Power not in a spirit of destructive criticism, but in a desire to be helpful. This does not mean […] that we are not deeply conscious of all that the British Mandate has meant for Palestine and for the Jewish National Home. All we ask is that the same largeness of vision and breadth of view which were shown in framing the policy should now be shown in carrying it into execution.’

In this volume, Weizmann’s exhaustive efforts, enduring six years, to form an enlarged Jewish Agency of Zionists and non-Zionists at last bore fruit. On 11 August 1929 the Constituent Assembly of the Council of the Jewish Agency for Palestine convened at Zurich, and a newly-forged Jewish instrument for the building of the National Home in Palestine came into being.

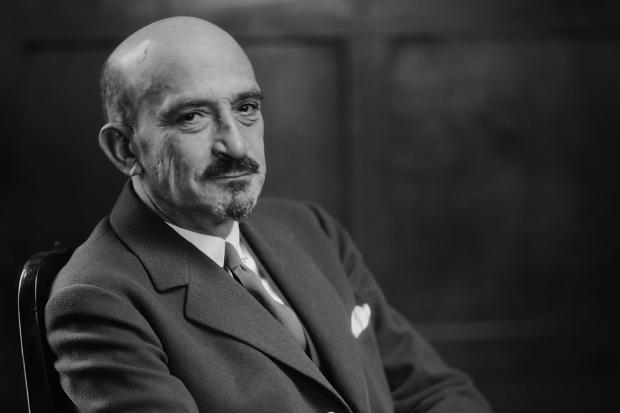

The architects of this body were Weizmann, President of the World Zionist Organization, and Louis Marshall, President of the American Jewish Committee. The negotiations between the two had begun in 1923 in accordance with Article Four of the Mandate, which charged the Zionist Organization to take steps ‘to secure the co-operation of all Jews who are willing to assist in the establishment of the Jewish National Home,’ and in pursuance of the resolution on the subject adopted by the 13th Zionist Congress. Two Non-Partisan Conferences, attended by prominent Jewish personalities of the United States, were convened in New York by Marshall in February 1924 and March 1925 and decided in favor of the participation of American Jewry in the Jewish Agency. The latter conference also resolved to appoint an Organization Committee to formulate definite plans for participation. By the summer of 1925 Marshall, on behalf of the non-Zionist group, and the Zionist Executive came to a provisional understanding on various technical points related to the constitution of the Agency.

At the 14th Zionist Congress, held at Vienna in August 1925, Weizmann’s understanding with the American non-Zionists was severely criticized by many delegates. They regarded co-operation with Marshall’s group as handing over the fate of Zionism to some Jewish ‘notables’, not democratically elected and therefore representing only themselves. Weizmann, however, succeeded in securing Congress approval for his action, and the support required to proceed with the negotiations. At last the road seemed to be paved for the establishment of the Jewish Agency, and hopes increased in September 1925 with the conclusion of ‘The Pact of Amity’ between the Zionists and non-Zionists in the United States.

The expectation was not to be immediately fulfilled. As the Zionist Executive’s Report stated, ‘developments in the United States were considerably hampered by a controversy which arose between the Joint Distribution Committee [where the non-Zionists predominated] which had launched a campaign for a 15 million dollar relief fund to be utilised largely for Jewish colonisation in Southern Russia, and the Zionist Organization of America, many of whose members regarded this campaign as likely to have a detrimental effect upon the Keren Hayesod collections, and indeed as a veiled attack on the Zionist movement. The Zionist Organization of America, feeling that a special effort was required to meet the requirements of Jewish work in Palestine, decided to organize a United Palestine Appeal, of which the leadership was entrusted to Dr. Stephen Wise […] Acrimonious debate unfortunately arose in the course of the two campaigns between the followers of both sections, and this inevitably affected adversely the friendly atmosphere which had developed before the last Congress, and impeded the Jewish Agency negotiations.’

Relations between the two parties were indeed almost completely severed. Both Weizmann and Marshall were perturbed by the situation which developed, and sought to extricate the Agency from its consequences. The plight of the National Home in Palestine and Weizmann’s conviction that urgent steps should be taken to establish it on solid foundations provided impetus for renewed effort to conclude negotiations. As Weizmann wrote to Marshall, this would clear the road ‘to establishing a productive, great Jewish community in Palestine, the members of which will be the carriers of a Hebrew civilisation worthy of our race,’ and ‘that is why you, dear friend, and those who work with you, and why we all should see that the work which has been initiated at enormous sacrifice should be continued with greater strength and in a greater style, and the road opened for a continuous influx of our people into Palestine […] Conditions should be created to secure their rooting in the country, and their transformation from luftmenschen into productive beings.’

Some time elapsed before action was resumed. ‘I realise that we would have to begin work on the whole matter in the Fall’, Weizmann wrote to Marshall in a ‘spirit of friendship and devotion,’ informing him that he was planning a visit to America then; Marshall expressed the hope that if Weizmann visited the U.S. ‘the harm that has been done may to some extent be cured, but it will not be a simple matter.’ Many points of difference were cleared in an exchange of letters, and a better atmosphere was created.

In October 1926 Weizmann arrived in America for resumption of the negotiations with the Marshall group. He submitted a plan of action for the enlarged Agency, as well as a budget necessary to carry out the proposed activities, and suggested that an independent body of experts undertake a comprehensive study in Palestine, to obtain a clear picture of what had been done there, to take stock of the situation and to make recommendations for the future. At the same time Weizmann labored to soothe tempers. In a well-publicized letter to Marshall he called for unity and urged the Jews of America to ‘forget past unpleasantness and bear in mind that regardless of differences of opinion we are all Jews, bound together by historic ties and with responsibility for the future. Our most imperative need just now,’ he wrote, ‘is for Sholom—peace among all the forces of American Jewry, in order to achieve such unity as will advance the highest interests of all Israel, here and everywhere.’ Marshall and his associates accepted ‘with profound satisfaction […] the proffered olive branch.’ On 17 January 1927, a formal agreement was signed by Louis Marshall and Chaim Weizmann expressing the unanimous accord in principle of both parties `as to the desirability and feasibility of organizing the Jewish Agency.’ The agreement provided for the constitution of a mixed commission to carry out a detailed survey of conditions and possibilities in Palestine and frame recommendations for a long-term program of constructive work there. It was intended that the formal establishment of the Jewish Agency should follow immediately upon the receipt of its report. ‘Here, at my end, the formal part about the Agency is completed,’ Weizmann wrote to his wife, ‘we now have to constitute the commission and then the new machine will be set up which, I hope, will bring about the required results.’

The constitution of the Survey Commission and the phrasing of its terms of reference were no easy task. Queries, objections, demands for clarifications, disagreements and problems of nominations and authority, caused some six months delay between signature of the agreement and formation of the commission with its terms of reference established. Many difficulties still lay ahead. Opposition forces within the Zionist Organization continued their struggle to frustrate the entire scheme, and launched an attack against Weizmann and his policy at the 15th Congress, held at Basle in August—September 1927. Weizmann gained the confidence of the majority at the Congress, but the debate and manner in which its resolutions were adopted aroused Marshall’s anxiety and suspicion as to Zionist sincerity.

The Joint Palestine Survey Commission submitted its report in June 1928. The findings of some of the experts on its staff proved highly controversial. Weizmann considered they distorted Zionist achievements in Palestine and would be misunderstood, with damage to the movement. He therefore proposed delaying publication of the report until the Jewish Agency negotiations were concluded, and the body established. Marshall rejected this proposal, and in October 1928 the report of the Joint Palestine Survey Commission was laid before a conference chaired by Marshall and attended by leading members of Jewish communities and organizations in all parts of the United States, Weizmann also participating. This conference accepted the report of the Joint Palestine Survey Commission as a basis for co-operation between the American Jewish community and the Zionist Organization within the framework of the enlarged Jewish Agency and arranged for representation of United States Jewry on the non-Zionist section of its Council. An Organization Committee to select the American delegates was set up.

Notwithstanding the resolutions of this third Non-Partisan Conference, new difficulties arose concerning the constitution of the Agency, the composition of its Council and Executive, the question of the Presidency, the method of electing non-Zionist members, and the dissolution principle. The inclusion of the term ‘National Home’ in the preamble of the Agency’s constitution also caused anxiety, and the position of the National Funds required lengthy discussion. In August 1929 the negotiations with the American non-Zionists were finally concluded. In the meantime conferences of Jews of other countries were convened to enable them to join the enlarged Jewish Agency and to make it the instrument through which the Jewish people the world over would unite in the effort to build up the Jewish National Home in Palestine.

This volume is also illuminating in matters concerning the early history of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Inaugurated in April 1925, the university was still struggling for recognition as an institution of higher learning, and to be a source of inspiration to the Jewish people. These letters convey the impression that controversies were developing against a background of personal ambitions or interests, but the real issue at stake was the character of the university and its lines of development as the university of the new Palestine. Weizmann, who played such a major role in its establishment, had always seen it as a symbol of Jewish reconstruction and national regeneration, embodying the spiritual ideal of the National Home. To him the Hebrew University had to provide the modern interpretation of the verse Tor out of Zion shall go forth the Law and the Word of the Lord from Jerusalem. There was a danger that the Hebrew University would be tempted to furnish quantity at the expense of quality, to strive for a large number of graduates rather than to establish a high intellectual standard. The aim of the university, Weizmann believed, should be to create this standard by serious research work, in particular in those branches of science which were connected with the reconstruction of Palestine, and by the study of the spiritual heritage of the Jewish people, thus establishing a vibrant contact with the new life in Palestine and with the living force of Jewish tradition.

The pressure and strain under which Weizmann was working affected his physical health, compelling several periods of withdrawal for medical treatment and cure. Yet it seems that the mental burden of leadership was more difficult to bear. ‘I don’t know why God has placed such a heavy burden on my shoulders, why fate chose me in order to direct the building in Palestine,’ he complained, ‘but it turned out like that. The chains of leadership are heavy, although sometimes they seem to be of gold.’

As previously, he considered resigning from the Presidency of the Zionist Organization, but it seems that a deep sense of responsibility to Palestine, combined with apprehensions that his resignation would have grave consequences for the proper development and direction of the movement, restrained him. ‘If I go away,’ he wrote, ‘the movement is likely to become extremist and lead to most serious complications.’ The reference was undoubtedly mainly to Vladimir Jabotinsky, his policies and the methods which he advocated. ‘Why raise a bogey [by creating a Jewish Militia in Palestine, which Jabotinsky was proposing at that time]?’ Weizmann wondered, ‘Why arouse all our enemies? all our opponents? It is midsummer madness. Nobody, except a few partisans of Jabotinsky, wants it […] I am sure that in a few years, say 3 years, the formation of a Jewish Militia may follow as a matter of course, and the point at present is to increase the population. We are 17 percent now. If the immigration continues at the present rate even we shall be 35 per cent or so in another 5 years. Much will change then. Any unwise step which we might take now, likely to retard the development, is a criminal offence against the National Home […] They [the Jabotinsky faction] try to discredit us in the eyes of the Government, Arabs and other outsiders […] The one thing needed now is to consolidate the position gained, get out of the present crisis so that the immigration could proceed securely. Any donquixotic attempts to get the Government or the Jewish people to spend money on Jewish armies is tomfoolery […] Jabotinsky is not satisfied with a militia. He wants an army.’ The Zionist movement and the Jewish National Home in Palestine would be navigated safely, Weizmann believed, only if he remained in control.

PINHAS OFER