The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann

May 1945 – July 1947

Volume XXII, Series A

Introduction: Joseph Heller

General Editor Barnet Litvinoff, Volume Editor Joseph Heller in collaboration with Nehama A. Chalom, Transaction Books, Rutgers University and Israel Universities Press, Jerusalem, 1979

[Reprinted with express permission from the Weizmann Archives, Rehovot, Israel,by the Center for Israel Education www.israeled.org]

The present volume of the Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann begins with the Allied victory in Europe and ends in the investigation of the Palestine problem by the United Nations Special Committee. Within this period Weizmann was reduced from being the President of the Jewish Agency and the acknowledged leader of his people to a lonely figure, virtually retired from public life. This was because he continued to place his faith, at least until the summer of 1946, in cooperation with Great Britain, the Mandatory Power, while his principal colleagues in Zionism were adopting the ways of violence in Palestine.

That one-third of the Jewish people had perished in war-torn Europe was known well before the termination of hostilities. This catastrophe had prompted the Jewish Agency to submit a Memorandum to the Allied Powers in October 1944, repeated in May 1945, demanding the early establishment of a Jewish State. The Agency asked for the immigration ‘within the shortest possible time’ of the first million Jews from Europe and the Moslem world into Palestine. The 1939 White Paper had permitted a maximum of 75,000 immigrants, and this quota was virtually exhausted so that now only 1,500 could enter monthly. The Memorandum, signed by Weizmann, detailed proposals for making room in Palestine for several million Jews within 10-15 years.

Immigration of the first million would enable the yishuv (the Palestine Jewish community) to become the majority, and provide for the ‘normal functioning of the Jewish State.’ The Agency contended that a clear-cut British decision in favor of such a state, if supported by the U.S.A. and Russia, was the only way to secure Arab consent. Equivocation on the part of the Powers would merely intensify Arab opposition which, according to the Jewish Agency’s version of the situation, was born of Arab conviction that the Balfour Declaration had not been seriously intended. The Agency’s Memorandum further demanded that, with the establishment of the Jewish State, an international loan should be arranged for the transfer of Jews to Palestine, and for the country’s economic development. It spoke of reparations from Germany to the Jewish people for the upbuilding of Palestine, and the provision of international facilities for Jews in transit.

As it happened, on the day of the Memorandum’s submission, 22 May 1945, Hugh Dalton, the future Chancellor of the Exchequer, stated at the Labour Party Conference at Blackpool in the name of his party’s Executive that it was ‘morally wrong and politically indefensible to impose obstacles to the entry into Palestine now of any Jews who desire to go there.’ He also emphasized that there should be ‘close agreement and cooperation’ among the British, American and Soviet Governments to ensure ‘a happy, free and prosperous Jewish State in Palestine.’

It will be recalled from the previous volume that the great regard for Zionism long evinced by Prime Minister Winston Churchill had much diminished, if only momentarily, with the assassination in November, 1944, of Lord Moyne. Nevertheless, Weizmann entertained strong hope that the Prime Minister would react positively to the Memo-randum, which was accompanied by a personal letter. It was therefore a shock to him to receive an evasive reply that spoke of postponing the Palestine question to the Peace Conference. Weizmann was not convinced that the Jews would be invited to a Peace Conference, and together with his colleagues he saw that, as far as Britain was concerned, no decision on Palestine was likely in the early future. Thoughts therefore turned towards America, and the hope that President Truman could be persuaded to intervene.

Moshe Shertok, head of the Political Department of the Agency, again raised the question of immigration in another Memorandum, to the High Commissioner of Palestine, then Viscount Gort, on 18 June 1945. He estimated the number of Jewish survivors as 1,400,000, excluding those in the Soviet Union. He emphasized the urgency of the problem in view of new outbreaks of antisemitism in Europe, citing as an example Poland, whose government admitted that in March, following the liberation, some 150 Jews had been killed. In Romania, 30,000 Jews had applied for emigration. Requests were pouring in also from Hungary. And some 70,000 survivors still living in camps in Central Europe were adding their voice to the clamor. Moreover, as events in Tripoli and Alexandria were soon to prove, the Jewish position in the Islamic countries of North Africa and the Middle East was also precarious. Shertok therefore requested an immediate grant of 100,000 immigration permits, one quarter ear-marked for orphans, to meet the most urgent needs.

Through the influence of Henry Morgenthau, Jr., U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Truman sent Earl G. Harrison, U.S. representative on the Inter-Governmental Committee on Refugees, on a special mission to investigate the situation of the Jewish survivors in Europe. Weizmann contributed to the initiation of this mission by urging Felix Frankfurter, Justice of the Supreme Court, to put his weight behind it; and indeed Harrison’s Report (1 August 1945) played a vital role in convincing Truman to support the Agency’s demand for the immediate transfer of 100,000 Jewish survivors to Palestine. However, Britain strongly resented Washington’s intervention, and an extended, fractious dialogue now ensued between the two Powers in this regard.

Meanwhile, dramatic events had been taking place in England. Churchill and the Conservatives were resoundingly defeated in the General Election of July, 1945. The return of a Labour Government, under Clement Attlee, could not but be welcomed by the Zionist leadership, given Labour’s frequent statements of support for the Jewish position. But a most painful disillusionment was in store.

The blow had not yet fallen as the first post-war World Zionist Conference assembled that August, bringing 96 delegates from 17 countries to London. Here, the simmering controversy between Weizmann and the majority of his Agency colleagues was forced into the open. Abba Hillel Silver, co-chairman of the American Zionist Emergency Council, Moshe Sneh, Commander-in-Chief of the Haganah, military organization of the Agency, and David Ben-Gurion, chairman of the Agency, all advocated active resistance to reinforce the diplomatic struggle. Weizmann, however, described this as irresponsible talk, and he voiced the hope that the Labour Government would ultimately, if not immediately, fulfill its promises to Zionism. But the majority of delegates were against him, and the activists won the day—a rebuff, though not yet a defeat, for their President. A British statement, to the effect that the 1939 White Paper regulations in regards to immigration and land transfers would for the time continue, came in September. This marked the repudiation by the Labour Party of its long-standing pledge.

Weizmann had his first meeting with Ernest Bevin, the new Foreign Secretary, on 10 October, and warned that unless Britain abolished the White Paper, the situation in Palestine, already tense, was bound to deteriorate. Britain would soon find herself ejected from the Middle East. Bevin replied that he doubted whether the grant of 100,000 immigration permits would solve the Palestine problem, but declared that he would stake his political career on its solution.

Some two weeks previously, Sneh had proposed to Ben-Gurion that, in addition to measures already in progress to bring in and conceal illegal immigrants, the time had come for direct action against the British authorities. Ben-Gurion gave his assent on 1 October, and as a consequence relations between the Agency and the hitherto recalcitrant Irgun and Stern Group were temporarily transformed. Eight years of mutual bitterness and hatred came to an end, a change all the more remarkable given that just recently the Haganah had engaged in action against the Irgun. Now the Haganah, the Irgun and the Stern Group were to operate under one roof, designated the Jewish Resistance Movement, that was controlled by what was known as ‘Committee X.’

Although Weizmann had himself lost faith in Britain, he strongly deprecated this move and dissociated himself from it. Only a small minority of moderate Zionists supported him (Aliyah Chadashah, a right-of-centre party established by former German Jews in November 1942, and Ichud, a group of intellectuals led by Martin Buber and Judah L. Magnes, President of the Hebrew University). Thus Weizmann began to identify with the opposition in Zionism, and as a consequence was kept in ignorance of developments taking shape in the Agency Executive, developments that resulted in the resignation of one of its members, D. Werner Senator. Although Weizmann never abandoned hope of bringing the movement back to moderation, his stand on this issue signaled the de facto end of his leadership.

Ben-Gurion had expressed categoric disapproval of Weizmann’s meeting with Bevin, threatening his own resignation, and Weizmann now saw that a difficult struggle lay ahead. Even Hashomer Hatzair on the far left approved of the Resistance Movement, though with the proviso that only those targets creating obstacles to immigration and settlement should be attacked. But they were soon to discover that Weizmann, rather than Sneh or Menahem Begin, leader of the Irgun, was their true ally.

The first specific anti-Government operation occurred on 10 October, when the Haganah elite corps Palmach (created with British assistance in 1941) released 200 immigrants detained at Athlit, near Haifa. A vastly more ambitious operation followed, on 1 November. The Resistance Movement attacked rail and water installations at 153 different points. This was a virtual declaration of war on Britain, yet Weizmann learned about the action only from the Press. He was about to leave Palestine for America, but before doing so he addressed a message to the Yishuv in which he condemned the use of violence and pleaded for restraint. But the majority of the Tishuu stood behind those who favored the activist policy of expanding the struggle against the authorities. Nevertheless, the Haganah was now careful to strike at targets which hampered illegal immigration, such as radar stations, police coastguard boats, and the country’s communications system, while the Irgun and the Stern Group continued to pursue their terrorist policy.

The confrontation between Britain and the Zionists escalated, particularly after a declaration of policy by Bevin in Parliament on 13 November, 1945. For the first time the decision which had been taken more than two months earlier was made public. Announcing the continuation of the White Paper policy, Bevin also spoke of the establishment of an Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, which would submit its report within four months. At a Press interview, the Foreign Secretary was reported as stating that he was ‘very anxious that the Jews shall not over-emphasize their racial position. The keynote of the statement I made in the House is that I want the suppression of racial warfare, and therefore if the Jews, with all their sufferings, want to get too much at the head of the queue, you have the danger of another antisemitic reaction through it all.’ This prompted the Zionists to pronounce Bevin himself an antisemite, and the Jewish reaction to his declaration of policy was one of growing militancy.

The assumption amongst the Zionist leadership, including Weizmann, was that Truman had fallen into a trap Bevin had prepared for him. Bevin wished to direct the Anglo-American investigation to all possible areas for immigration, and to include Jewish rehabilitation within Europe. In fact, Truman resisted this, and insisted on making Palestine the focus of the inquiry.

Weizmann roundly condemned Bevin’s statement, in public at an American Zionist Convention, and in a letter to Frankfurter in which he denounced it as ‘brutal, vulgar and antisemitic.’ In an interview with Truman, which he reinforced with a memorandum, he implored the President to endorse the Zionist solution for Palestine, arguing that the establishment of the Jewish State would terminate the Arab Jewish conflict rather than intensify it. Within Palestine, anti-Government demonstrations erupted, resulting in fatal casualties. The authorities tightened surveillance of the coast, so that most ships bringing in illegal immigrants were intercepted. The Palmach thereupon destroyed coastal police stations, and the British retaliated with searches of nearby settlements. The Haganah tried passive resistance, but the authorities replied with force, and more people were killed. In late December 1945, the Irgun and Stern Group raised the scale of their activities.

On the Arab question, Weizmann was in complete agreement with those in the Zionist Organization who differed from him regarding Britain. He informed Truman: ‘Arab leaders should be told frankly that all they have gained in freedom and inde-pendence as a result of the two world wars, came not from their own efforts but from Great Britain, the U.S. and their allies, and that in the war which has just ended they were saved from Nazi and Fascist enslavement. Great Britain and the U.S. have, therefore, the right to ask from them that they should not hinder the settlement of one of the world’s most acute problems—the homelessness of the Jewish people—a problem which can only be solved in Palestine, a small notch in the vast underpopulated peninsula, which can, anyhow, never be purely Arab again because of the presence of 600,000 determined Jews.’

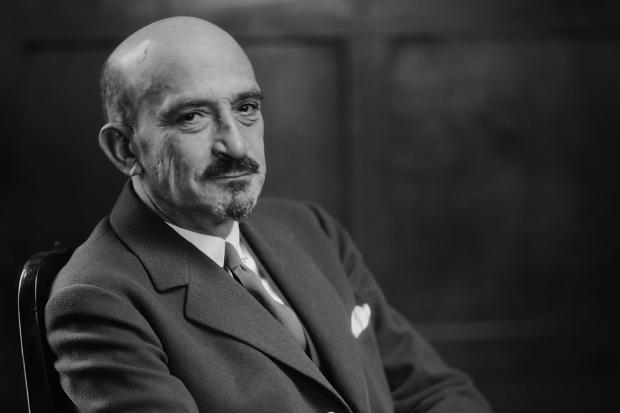

Meanwhile, the Anglo-American Committee had been hard at work. Weizmann gave his evidence on 8 March 1946, in Jerusalem. His address made by far the greatest impression of all the Zionist witnesses. Richard Grossman, an English member of the committee, wrote: ‘We had Weizmann, who looks like a weary and more humane version of Lenin, very tired, very ill […] He spoke for two hours with a magnificent mixture of passion and scientific detachment […] He is the first witness who has frankly and openly admitted that the issue is not between right and wrong, but between the greater and the lesser injustice.’

After discussing the nature of antisemitism, Weizmann claimed that it was possible to double and even treble the population of Palestine without expelling the Arabs. He pointed out that before 1939 he had never hesitated to emphasize his moderation and, unlike the Revisionist leader Vladimir Jabotinsky, had refused to announce publicly that a Jewish State was the ultimate aim of Zionism. But the Holocaust had changed his view. A permanent Jewish minority in Palestine was a dangerous contingency, given the experience of Jewish and other minorities in the Arab countries. Further, he pointed to the insignificance of the Arab contribution to the Allied war effort as compared to the Jewish, yet six newly-independent Arab states had been accepted as full members of the U.N., and one even as a member of the Security Council.’

Evidently, Weizmann’s differences with his colleagues were mainly tactical: the Jewish State was beyond argument. But Weizmann wished to proceed at a slower pace than Ben-Gurion. Thus, when questioned about the practicability of the immigration of 100,000 survivors in one year, he indicated that this might perhaps take two years. Undoubtedly, no other Zionist witness conveyed such sincerity. However, he was required to atone for his evidence the following day, when a storm of indignation met him in the Agency Executive. Weizmann was accordingly asked to correct his evidence and to say that the 100,000 could in fact be absorbed within a year.’ Not surprisingly, the High Commis-sioner commented that the Zionist leader had lost his authority over his people.

Weizmann disagreed with most Executive members on another issue: he wanted such minority groups as Hashomer Hatzair, Aliyah Chadashah and Ichud to appear before the Anglo-American Committee. But the Executive decided against it, as these groups were opposed to the Biltmore Programme, now the official policy of the movement, for a Jewish State in the whole of western Palestine. As Weizmann pointed out, the committee was bound in any event to learn of such views, and he denounced the Executive’s ‘totalitarian’ behavior as ‘a very grave mistake,’ and drew the inevitable conclusion. He decided in April 1946 to abandon all thought of seeking re-election as President of the Zionist Organization and Jewish Agency at the coming Congress. He would leave Ben-Gurion and Silver ‘to fight it out between themselves.’ Ben-Gurion’s rise did not disturb him so much as the possibility of the election to the Presidency of Silver, with his uncompromising hatred of Britain and hostility towards the progressive sector of the yishuv. In Weizmann’s view this could produce a situation in which Britain might liquidate the Agency. As for himself, he wrote: ‘I can’t be just a figurehead, assuming formal responsibility for other men’s actions without taking any real hand in the work.’ Eight months were to pass before circumstances compelled him to relinquish his office.

Having concluded its investigations in Washington, London and the Middle East, the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry betook itself to Lausanne to consider its Report. The Agency placed an unofficial delegation in nearby Montreux to maintain contact with its pro-Zionist members: James G. McDonald, Bartley Crum, Frank Buxton and Richard Grossman. Headed by Shertok and Nahum Goldmann, this delegation saw the prospects for Zionism imperiled by the deep cleavage within the committee. Three English members, including their chairman Sir John Singleton, defended Bevin’s policy. The key to the situation lay with the neutral American members, particularly their chairman, Joseph C. Hutcheson. He demanded a compromise to avoid the danger of two reports being submitted, one by the pro-Zionist minority and the other by the anti-Zionist majority. A compromise was achieved, both because the unofficial Agency delegation advised the pro-Zionist members to agree to it, and because of the intercession of Philip Noel-Baker, Minister of State at the Foreign Office, who visited Lausanne specially for the purpose.

On 20 April 1946 the committee announced its conclusions. It favored the abolition of the White Paper of 1939, the immediate immigration of the 100,000, and the removal of restrictions on land purchase dating from 1940. This was a victory for the Zionist moderates, and Crossman hoped thereby that Weizmann might now regain control of the movement. But it was off-set by rejection of the claim for a Jewish State. There was to be no Arab State either. Instead, the committee recommended that the Mandate be transformed into a trusteeship.

Zionist reaction to the Report was generally jubilant. Weizmann and the majority of the Jewish leadership saw it as opening the road to a great increase in the population of the rishur, within a relatively short period. But Ben-Gurion tended to stress the negative findings.

Enthusiasm was doomed to be short-lived, for Attlee made implementation of the Report dependent upon the disarming of the Jewish population. This was an impossible condition and totally unacceptable to the Agency, which claimed that, in the event of British evacuation, the yishuv would be left defenseless. And even without evacuation, as was proved during the Arab Revolt of 1936-39, a Jewish armed force was necessary. In fact, the Agency offered Britain military bases in a future Jewish State. But all this was to no avail, since the British Government was determined to reject the Inquiry Report.

Weizmann and his colleagues in the Agency Executive were now filled with anxiety as to the possible repercussions of Attlee’s position, for the likely outcome would be an increase in tension between Britain and the yishuv. Weizmann felt that, had Attlee made implementation of the Report dependent on the stoppage of terrorism, the Agency would have cooperated. But Government policy as stated implied rather the liquidation of the Jewish National Home. Weizmann now warned Attlee in unambiguous language that if his Cabinet would again delay a solution of the Jewish question, ‘there is certain to be trouble both from the Arabs who will be encouraged by this to back up their threats by action, and from Jewish extremists prepared to resort to violence.’

He briefly entertained the hope that the Report might somehow be saved, but Bevin shattered this on 12 June when he underscored Attlee’s argument that the Arabs would strongly resist its implementation: an additional army division would be needed in Palestine. The next day two members of the Irgun were sentenced to death by a British military court. Weizmann, though a declared enemy of terrorism, pleaded with the authorities to commute the sentences. He wrote to Sir Evelyn Barker, G.O.C. Palestine, that ‘however wrong or misguided these young men may be, they have not acted from criminal motives, but because of a deep-seated feeling of a great injustice done to their people.’ The two were saved from the gallows, but the British decided to take the strongest measures to break the collaboration between the Agency and the terrorists, for a virtual rebellion had begun. The High Commissioner, now Sir Alan Cunningham, had already reported to London that ‘recent events have demonstrated that Weizmann is deliberately kept in ignorance of the seamy side of Jewish political activities.”

The Jewish Resistance Movement went into action on a large scale on 16-17 June 1946, having first, through the Agency, secretly consulted two friendly British politicians as to the likely efficacy of the operation. The Palmach blew up the bridges connecting Palestine with the neighboring countries, while the Stern Group attacked the railway workshops at Haifa and the Irgun took six British officers hostage lest their own members be executed. The British then struck. Their plan was discovered and made public by Kol Israel (`The Voice of Israel’), the clandestine radio station of the Haganah.’

Cunningham summoned Weizmann and warned him that the National Home would be lost in ‘a welter of bloodshed and desolation’ if actions involving murder, kidnapping and sabotage did not cease, for the strain on the troops was unendurable. Weizmann did not defend these actions, and indeed the High Commissioner realized that the Jewish leader had little influence on the extremists, and was deliberately avoiding any foreknowledge of terrorism. But Weizmann contended that the ‘Night of the Bridges’ was the result of an accumulation of shocks: Bevin’s speech of 12 June, the ex-Mufti’s return to the Middle East from Europe, the imposition of the death sentence on two Jews, the readiness of Glubb Pasha, Commander of the Arab Legion, to participate in operations against the yishuv, and the discovery of a ‘Black List’ of Jews to be arrested. Ben-Gurion used a similar argument in an interview with George Hall, the Colonial Secretary, in London the same day.

Nevertheless, Weizmann was about to send an ultimatum to Shertok when the British operation (code-named by them ‘Agatha’ and described by the Jews as ‘Black Sabbath’) took place. Unless the Agency ordered the stoppage of violent terror, he would resign. He rejected the argument that the ‘Night of the Bridges’ had been cleared by British friends, and that there was a precedent in the revolts of the Arabs, and the Irish, and the Boers. The Jews were a highly vulnerable minority, with a different objective—to gather in their exiled people. In a letter that could not be delivered because Shertok had been arrested, he stated: ‘I cannot continue to play the part of a respectable facade, screening things which I abhor, but for which I must bear the responsibility in the eyes of the world.’ He continued: ‘Unless political violence is abandoned, definitely stopped, and every effort made to bring the Etzel [Irgun] and Stern people to obedience, to moral discipline, until the Organization has had a chance to review the whole situation at the next Congress, I shall feel compelled to resign my office now […] the very next act of sabotage will automatically bring about my resignation.’

The British operation took place on Saturday, 29 June 1946. Its intention was to cripple the Palmach; to arrest Agency leaders suspected of links with the Haganah, and to deprive it of its leadership; and to find documents which would prove beyond doubt the connection between the Agency and the Haganah. Besides Shertok, Agency Executive members, arrested and brought to detention at Latrun were Rabbi J. L. Fishman, Isaac Gruenbaum and Bernard Joseph. Another leader taken was David Remez, chairman of the Va’ad Leumi. Sneh, Commander of the Haganah, managed to escape, while Ben-Gurion was abroad. The offices of the Jewish Agency were searched, and documents discovered there were published. In addition, 27 settlements were cut off, and extensive searches were mounted for arms and suspects. Altogether some 3,000 people were arrested, some of them being treated brutally, but only 200 of them were Palmach members. The Commander of the Palmach later admitted that the detention of this manpower caused considerable economic damage. It was therefore decided by the Agency that those

arrested would agree to identify themselves. This signified a retreat from the former stand, which insisted on one reply both for legal and illegal Jewish residents of Palestine: ‘I am a Palestinian Jew.’

In another heated interview, Weizmann and Cunningham charged each other with a ‘declaration of war.’ Weizmann, whom the High Commissioner described as ‘very distressed,’ implored the other not to let events drift—the Jews could never be ruled by force. Cunningham stated that the situation could be eased if the Jews laid down their arms and assisted in suppression of the Irgun and Sternists; the Jewish Agency was working ‘behind Weizmann’s back in the control of the Haganah.’ Apparently Weizmann did not disagree, and ‘took in the idea of negotiation in regard to the Jewish armed forces.’

The Haganah retaliated by attacking an army camp holding much of the confiscated arms. Furthermore, ‘Committee X,’ to which the Resistance Movement was responsible, approved the plan for an Irgun attack on the King David Hotel, and a Stern Group plan for attacking a large building nearby.

At this critical stage Weizmann sent word to Sneh through his personal aide Meyer Weisgal demanding the suspension of all violent activities on the part of the Resistance Movement until the Executive could decide future policy ; otherwise he would resign. The ultimatum was communicated to ‘Committee X.’ Sneh wanted it rejected, but was outvoted.” He himself resigned, and in consequence the Jewish Resistance Movement dissolved itself. Thus although Weizmann could not control the Irgun and Stern Group, so far as the Haganah was concerned he now had assurance that such actions as the ‘Night of the Bridges’ would not be repeated.

After almost a year, Weizmann had therefore achieved a distinct victory over the majority on the Executive. But he did not delude himself that the fight had ended. He left Palestine on 17 July in the knowledge that he must continue the struggle against Britain’s policy, which he described as maintaining the ‘worst form of military dictatorship.’ The real authority in Palestine was not Sir Alan Cunningham, the High Commissioner, but the G.O.C. Palestine, General Barker, who was not innocent of antisemitism. According to Weizmann, the intention of the military was to destroy the yishuv by provoking the Jewish population. They would not hesitate to use artillery and to bomb Tel Aviv. But his efforts, aided by his friend the veteran British Zionist Harry Sacher, prevented violent reaction on the part of the Yishuv.

If the British assumed that ‘Operation Agatha’ would clear the way to the formation of a moderate Executive run by Weizmann and his supporters, together perhaps with such members of Mapai as Eliezer Kaplan and Joseph Sprinzak, they were to be disappointed. In fact it helped to narrow the gulf separating him from his opponents. Weizmann drew up a three-point plan for clearing the atmosphere with the British: release of the detained leaders; grant of the 100,000 certificates; and termination of General Barker’s military rule. The plan was not intended to revive the old Anglo-Zionist collaboration, for ‘Black Sabbath’ had signaled for Weizmann the end of the historic relationship: ‘I, as a firm believer in, and champion of that relationship, am forced to realise that what has been destroyed is so deep, so vital, and of such moral significance, that it cannot be restored by projects, resolutions and kind words. I feel […] that the only way to establish normal relations between the two peoples is to partition Palestine, and set up an independent Jewish State in treaty relations with Great Britain.’ On 22 July the Irgun blew up the King David Hotel, which housed the Chief Secretariat of the British Administration. In an attempt to prevent casualties, the Irgun gave the authorities advance warning, which, unfortunately, was not taken seriously. Nearly a hundred people, British, Arabs, and Jews, were killed, with many more injured.

Nevertheless, the Government pressed forward in its efforts to secure American support for its Palestine policy. A new bi-national committee was endeavoring to work out the technical details of the Anglo-American Report. This produced what became known as the Morrison-Grady Plan, whereby Palestine would be cantonised into four provinces under British trusteeship, with 100,000 immigrants permitted within one year. As formulated, the plan (which in fact was similar to one lying in Colonial Office pigeon-holes since 1943) was declared unacceptable by both Arabs and Jews. However, Herbert Morrison, Lord President of the Council, stated that Britain would invite both parties to a conference to discuss it. On the other hand, Churchill recommended in a Parliamentary debate that Palestine should be evacuated if America did not share ‘the burden of the Zionist cause.’ The Government regarded such a step as premature.

Following the dissolution of the Jewish Resistance Movement,Weizmann decided, to the indignation of his Agency colleagues, to renew contacts with the Colonial Secretary. Moreover, he became convinced of the desirability of reviving the enlarged Jewish Agency, by joining hands with the non-Zionists on the 1929 basis. Under such an Agency, the recent dangerous and regrettable events would never have taken place. The high probability that the question of Palestine would again be thrown into the melting-pot caused him great anxiety. As he wrote to Churchill: ‘If the present trouble is not settled quickly, and the tension reduced, I tremble to think of the consequences—not only in the Middle East, but also in relation to the United States.’

In a letter to Hall following a discussion, Weizmann demanded that before the London Conference convened, ‘some détente’ should be established between Britain and the yishuv, i.e., suspension of the searches and release of the detained leaders. He described the Morrison-Grady Plan, proposed by the Government as a basis for the conference discussions, as ‘unduly narrow: we need to have wider boundaries.’ He had in mind above all the Negev.

The Jewish Agency Executive met in Paris on 5 August 1946. Because of ill-health, Weizmann could not attend, and was represented by Sir Simon Marks and Weisgal. The meeting, which included several other leaders not members of the Executive, realized that with the failure of resistance Weizmann’s policy was the only alternative remaining. This resulted in the restoration of a common front between the Zionist President and his colleagues. He wanted to make a new approach to Washington, and Goldmann was sent there to win American support for an initiative in favor of partition. It was explained to the British that the Agency could join the conference on Palestine only if the principle of a Jewish State in an adequate area came into the scope and purpose of the discussions. The Zionists admitted that the Morrison-Grady Plan did not exclude partition as an eventual outcome of cantonisation, but it also envisaged a federal state. The Agency now insisted on two more conditions: full freedom to designate its own delegates to the conference; and prior consultation as to which non-Agency Jews should be invited to join the Jewish delegation. All these conditions created a stalemate in the preliminary discussions, and Weizmann’s efforts to break it through the intercession of powerful friends proved unavailing. But he felt that adherence to the condition of a Jewish State strengthened the Agency’s hand with the Yishuv and enabled it to enter the conference with dignity. He was far from optimistic, but felt strongly that ‘we shall be committing a sin against the movement and against the Yishuv if we do not explore even the slightest possibility of reaching a solution acceptable to us.’ After some doubt, and a renewed threat of resignation by Weizmann, informal talks with the Government began on 1 October.

By now Ben-Gurion himself had come closer to Weizmann’s line, writing the following to him on 28 October: ‘Whatever your views are on all this you remain for me the elect of Jewish history, representing beyond compare the suffering and the glory of the Jews. And wherever you go you will be attended by the love and faithful esteem of me and my colleagues. We are the generation which comes after you and which has been tried, perhaps, by crueller and greater sufferings, and we sometimes, for this reason, see things differently; but fundamentally we draw from the same reservoir of inspiration–that of sorely tried Russian Jewry—the qualities of tenacity, faith and persistent striving which yield to no adversary or foe.’

On 5 November the detained leaders were released, and in addition, some illegal immigrants interned in Cyprus were permitted to proceed to Palestine. Not unjustifiably, Weizmann drew hope from these gestures, encouraging his decision to attend the 22nd Zionist Congress in Basle the following December—the first such gathering since 1939 and the destruction of European Jewry. He was sure now that he would be re-elected to the Presidency.

The strongest party was the General Zionists, whose two factions had combined to form a united party holding nearly 32 per cent of the mandates. Labour, the leading party in 1939, was reduced in strength by the secession of two of its constituent groups and came second. Mizrachi was third, and the Revisionists, having abolished their own separate organization and returned to the fold, were fourth. Still smaller groups made up the rest. However, Palestine taken alone produced far different results. There, Labour (i.e., Mapai) was the strongest party, followed by the Revisionists, with the General Zionists in seventh place.

Two days before the opening of the Congress, Blanche Dugdale, Weizmann’s close adviser, had a discussion with Shertok and wrote: `I am sure that […] Chaim is deceived about his position. It is not so strong as he thinks, unless he turns it by his opening speech, which he has touched up today in the direction of making it more pro-British. I think this is a mistake.’

The speech began with rejection of the Morrison-Grady Plan and a demand for a Jewish State. Weizmann then condemned Jewish terror. Unless this was brought to an end, ‘Zionism is dead as a constructive political movement for generations.’ He was supported by Stephen Wise and Goldmann. The opposition, led by Silver, favored active resistance without distinguishing it from terror. Ben-Gurion took a middle line, and as the Congress proceeded he consented to support partition. At a secret session of the Political Committee, Ben-Gurion sounded a warning regarding war with the Arabs in a matter of two or three years, and against which he had begun taking precautions in the summer of 1945.

Weizmann now saw that even though his policy was no longer rejected, at least by the Executive, the opposition to him was insurmountable. Ben-Gurion, author of that recent letter of adulation, now collaborated with Silver, and the veteran leader was displaced. The crucial vote took place on 23 December, when the Congress adopted Silver’s proposal to reject participation in the London Conference. Weizmann at first reacted mildly to his defeat: he would now have more time to devote to his Institute of Science in Rehovot. As to the political lessons, the Congress might now indicate to Britain that it ‘must come to some sort of decision if the position is not to deteriorate altogether, and end in disaster—which we should all deplore. And I believe, too, that now that our Opposition has acquired some measure of responsibility, they may learn that political work is not exactly a sinecure.’

Later, on learning of the methods employed by Ben-Gurion and Silver to remove him, his attitude towards the new Executive elected at Basle became bitter and uncompromising. He sought to establish a new progressive group of General Zionists, comprising the few people still loyal to him: Marks, Lord Rothschild, Isaiah Berlin, Leonard Stein and Abba Eban in England; and Robert Szold, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Joseph Proskauer, Henry Monsky, David Ginsburg, Louis Lipsky and Eliahu Epstein (later, Elath), Wise and Weisgal in America. He warned his friends against the domination by Silver of the Zionist movement and Jewish Agency, commenting: `The delegations [at the Congress] could not vent their bitterness on the British Government, and I was the scapegoat nearest to hand […] This Congress, standing as it did by the graves of six millions of our people, was not yet inspired to forget or rise above petty intrigue and personal ambition.’

Weizmann’s resentment came to the surface with full force early in 1947. ‘I find it quite difficult,’ he wrote, ‘to collaborate with the present Executive which, in my opinion, is less a coalition and more a Noah’s Ark, with two each of all the animals—clean and unclean, and I very much fear that the unclean ones have the upper hand.’ At this point he decided to recruit his French friends to his new progressive group: Leon Blum, Andre Blumel and Marc Jarblum. But he soon postponed further action so as not to hinder the Agency’s efforts during the informal London Conference which re-started, despite the Congress decision and against an atmosphere of renewed terror and harsh British counter-measures in Palestine, on 29 January 1947. The authorities warned the Agency that they would have to declare martial law in the country, and demanded the Agency’s collaboration on the 1944-45 model against the terrorists. The Agency rejected this suggestion outright, declaring that only free immigration would stop terrorism.

Meeting with Arabs and Jews separately, Bevin sought without success to persuade both sides to relent from their inflexible positions. He put forward a new proposal which signified a retreat from the Morrison-Grady Plan. This provided for continued British trusteeship with local autonomy, for the immigration of the 100,000 in two years, and the creation of an independent bi-national unitary state after five years. This too was unacceptable to both Jews and Arabs. The former could not agree to anything less than a Jewish State in the greater part of Palestine, while the latter demanded an Arab State in the whole of Palestine. Bevin therefore announced that, negotiations having failed, the problem would be referred to the United Nations.

Some British experts, notably Harold Beeley of the Foreign Office, were confident that the Zionist case would be defeated at the U.N., and indeed many Jews held the view that Britain would not surrender Palestine. But all the signs indicated otherwise. The British, sorely tired at home by a critical economic situation, were taking steps to quit India, and to hand over to America their military responsibilities in Greece, Turkey and Iran. Palestine was in fact too costly a burden, and Weizmann himself noted that the end of Britain’s rule in India was bound to lead to a reassessment of its role in Palestine. Finally, in a dramatic volte-face, the Soviet U.N. delegate declared that Russia would favor partition if a scheme for a bi-national state proved unworkable. The General Assembly decided on 14 May to send out a Special Committee (UNSCOP) to investigate the situation. Its members consisted of representatives of eleven smaller nations under a Swedish chairman.

It was the end of an epoch. Palestine was now a problem for the international community; and as the nations took stock of the situation, the Irgun intensified its struggle. Relations between the yishuv and the British authorities were now at their lowest. Four members of the Irgun were executed, and the terrorists retaliated with the hanging of two British sergeants. Scenes enacted at Haifa harbor with the arrival of the illegal immigrant ship Exodus served to advertise to the world a savage conflict between a desperate, homeless people and a heartless Great Power. The urban centers of Palestine were placed under martial law.

Though at first unenthusiastic about transfer of the problem to the U.N., Weizmann began to see this as the last chance for Zionism, provided the Jewish case was properly prepared. He remained unforgiving for his treatment by the Congress, lamenting at what he termed possible ‘fascist’ developments in the movement, which had fallen into the hands of ‘false prophets and false priests.’ It vexed him that the Agency found itself completely helpless vis-a-vis terrorist activities. As a remedy he suggested that it join with the American Jewish Committee and the Anglo-Jewish Association, both non-Zionist bodies, to formulate a constructive policy. He feared for the future of the yishuv: ‘What is the good of collecting so many millions for Palestine when one is standing on the brink of a precipice?’

The Agency had decided that Weizmann should appear before UNSCOP as spokesman for the Va’ad Leurni. He preferred, however, to appear in his private capacity. Unlike the situation sixteen months earlier, he could now speak his mind freely, without the Agency’s tactical censorship. Thus he pleaded, in his evidence on 8 July 1947, for a clear-cut solution. Unlike the new Executive, he avoided vagueness and eloquently claimed that partition had the qualities of ‘finality, equality and justice.’ Jorge Garcia-Granados, Guatemala’s representative, recorded the deep impression that Weizmann made on the committee members. Even its most extreme anti-Zionist member, Sir Abdur Rahman of India, was moved to modify his generally violent tone. As in his evidence to the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, Weizmann emphasized the homelessness of the Jewish people, and its long and tragic history. He rejected out of hand the federal and cantonal plans suggested by Britain in July 1946 and February 1947, and was ready instead to accept a federal plan for Palestine only on a basis of partition. Federation could be established only in such areas as customs, currency and free transport. He explained that he saw the Jewish State in terms of the Peel proposals, plus the Negev, which would enable the absorption of 1.5 million Jews from both Europe and the Islamic countries. However, he had to admit that perhaps only 900,000 would be in need of immigration.

Weizmann’s evidence before UNSCOP, his correspondence with its chairman in July 1947, and above all the impression he made on its members, proved that although out of office he continued to carry great weight. He believed that the Jewish people, as distinct from the professional Zionist elite, would have to call him back sooner or later. This was indeed the case in a matter of months when developments both at the U.N. and in the U.S.A. needed the strength of his statesmanship and reputation.

Throughout this period we find Weizmann immersed in science as well as in politics. He had set his heart on a great expansion of the Sieff Institute and its development into the Weizmann Institute of Science. He was deeply concerned also in the growth of the Hebrew University, of which he was chairman of the Board of Governors, and the Haifa Technical College. Throughout his life science had been his refuge when politics brought strains in his relations with his colleagues. He saw science as making a small Jewish State into a great one. Greatness was not to be defined in terms of armies, tanks and planes. The future belonged to the scientist.

Constantly battling against ill-health, with partial blindness, he was absorbed in yet another activity: writing his memoirs, in collaboration with the author Maurice Samuel. Extracts were being published in Hebrew translation in the leading liberal non-party daily, Haaretz, which supported Weizmann politically throughout this period.

The present volume ends in the midst of the political struggle. UNSCOP completed its report at the end of August 1947, deciding, as Weizmann had recommended, in favor of partition. He could now see ‘a glimmer of light at the end of the long tunnel.’ The Jewish people were at the final stage of the long road to the establishment of the State of Israel. History was soon to prove that Weizmann’s life-long vision was forged of stuff more solid than dreams.

JOSEPH HELLER