From July 1971 to May 1973, we lived in Jerusalem’s Beit Hakerem neighborhood, then only a walk across an open valley to the Givat Ram campus of The Hebrew University. No high-rise hotels there then. Lots of stray cats and schoolboys playing soccer in the street.

Prior to leaving for Israel to carry out dissertation research, I had been warned in a letter by a young prominent Hebrew University professor, Yehoshua (Shuka) Porath, not to search for a doctoral topic that touched on Israel’s pre-state period. ‘Too much is being written, nothing new to discover,” he said. “My students are all writing on the Palestinians in the ‘20s and ‘30s.” I paid no attention to his warning. Quite accidently, I found 3,000 boxes, 12 files-to-a-box, of untouched Palestine administration land registry documents. In detail, they revealed how the Palestinian Arab leadership manipulated the livelihoods of the majority peasant population for most of the Mandate. From Shuka, I would eventually read the sources, and learn why and how the Arabs lost Palestine.

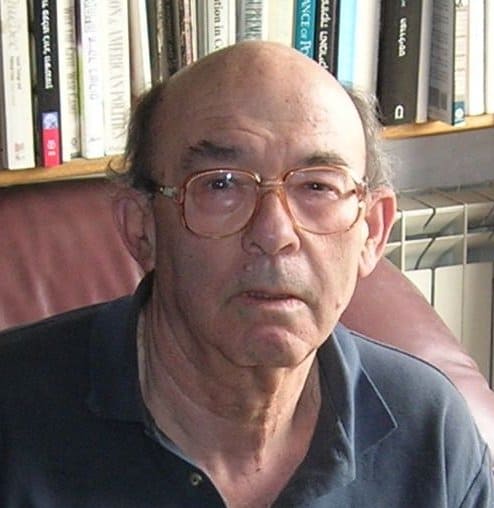

Quite coincidently, Professor Porath lived across the street from us on Rehov Hehalutz. Shuka was 5-foot-6 with thick glasses, possessing a brilliant, penetrating mind, and very quickly a love for my wife Ellen’s chocolate cake. Shuka was a scholar. He had impeccable standards. He read voraciously, loved history of all genres. Gradually, in Israel, he became my guide and mentor, and then for a lifetime of writing, I would ask, “What would Shuka say about the work I just completed?”

When we met weekly at his apartment, he routinely pointed me to the next file folder in the archives that would reveal something new about Palestinian Arab and inter-communal societal clashes. Porath had just finished writing the two most important books to date written on the emergence of the Palestinian Arab national movement. He taught several generations of students who would play important roles in the Israel Defense Forces, business and government, and trained dozens of Israelis who would teach subsequent generations. He was among the greatest of Israeli scholars in the second half of the 20th century.

Over the last several years, I have attended and participated in national Jewish conferences where Israel was gingerly discussed among Jewish youth, their mentors, rabbis and benevolent donors. Porath would have torn anyone apart who defended the notion of parallel narratives. For him, history was one story, complicated, nuanced, always woven together diligently and carefully by sources. Porath would not have tolerated concepts like post-modernism, best defined “as a version of the truth,” or political correctness, or accepted the premise that Israel is “too toxic to discuss.” All that mattered to him was the unreachable search for the objective truth, and if your personal sensitivities got in the way, Shuka would bellow at you for compromising intellectual rigor.

Shuka Porath was himself a standard of extraordinary excellence. Moreover, I was simply lucky because he lived across the street, he cared, and he taught me mentorship. He died on November 24, 2019, at 81. He remains my beacon for a professional lifetime.

Ken Stein is a professor at Emory University and president of the Center for Israel Education.