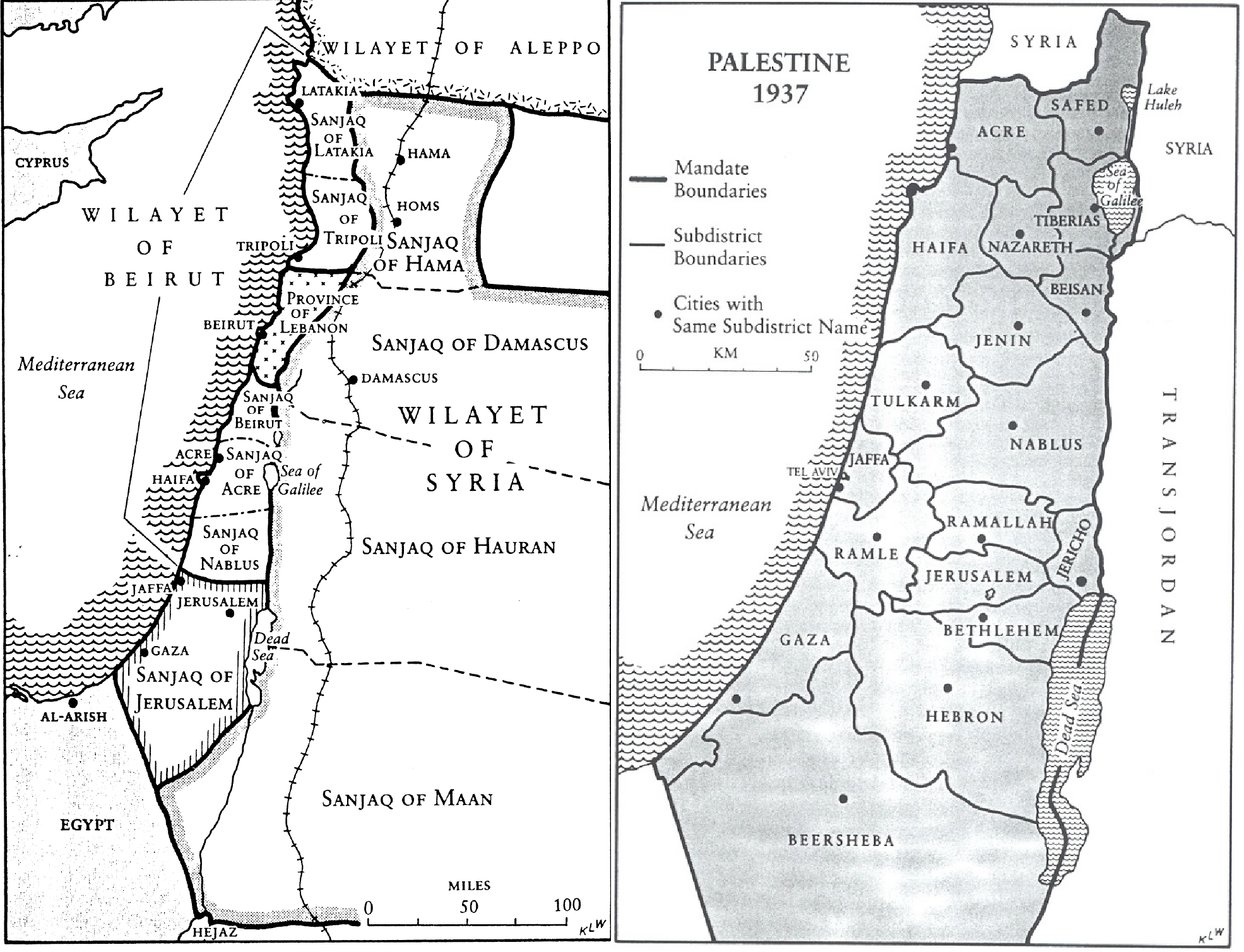

When the British and the French decided on the borders of some modern Middle Eastern states in the Levant in the 1915-1922 period, no Palestinian, Syrian, Iraqi, Jewish, Lebanese or Jordanian state existed.

Before the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Jews purchased two-sevenths of the cultivable land in Mandatory Palestine — some 2 million dunams or 500,000 acres — almost all north of the city of Beersheba. They acquired one-quarter of these 500,000 acres before the British Mandate began in 1920. The total land area of all of Palestine west of the Jordan River under the British Mandate was some 26 million dunams.

The remaining five-sevenths of the cultivable land was owned by Arabs or was administered by the British and previously by the Ottomans as state or dead lands.

The division of the Middle East was officially made by the great powers at the San Remo Conference in 1920 and was ratified in 1922 by the League of Nations, led by many of the same great powers.

“Owned” could mean held by individuals who possessed registered title deeds to those lands or by those who habitually worked the land but did not have title deeds because the area was not registered officially or because these agricultural laborers feared registering lands because the land registries were directly linked to Ottoman registers used for military conscription. In the 1930s under the British administration’s Protection of Cultivators Ordinances, aimed at keeping agricultural workers tied to their lands, Palestinian Arabs who were agricultural and tenant workers petitioned to claim ownership of lands because they or family members had used and worked the lands — grazing flocks, growing crops or residing — for years or decades. Claimants showed local Palestinian Arab magistrates their “evidence of ownership”: agreements they made with land agents, money lenders or landlords, often not signed but dated.

During the Mandate, the British, not motivated to turn lands over to either Arabs or Jews but wanting to order land rights for tax assessment purposes, surveyed some 50% of Palestine’s built-up areas by 1948 to determine the dimensions of land claimed. The Ottoman authorities had not kept orderly registration records, and none had exact dimensions. Furthermore, land records — title deeds or kushans — in some areas of Palestine were destroyed as the Ottoman Turks retreated northward to escape the British advances in 1917 during World War I. So disheveled and incomplete were Palestine’s land records that the British military administration temporary suspended all land transactions from 1918 to 1920.

The total cultivable land of Palestine was 13 million dunams, almost all of it north of Beersheba. South of Beersheba in the Negev and the Judean Hills were not cultivable but made up about half of Palestine’s total area of 26 million dunams, or 6.4 million acres. So Jews purchased approximately 7.6% of all the land in Palestine and 28% of the cultivable land in Palestine before May 14, 1948. The areas that the Zionists purchased in rural and urban areas enabled them to situate educational and agricultural institutions, build villages and towns, establish small industries, and evolve self-governing agencies and organizations that served the Jewish population of the state in the making.

Jewish immigration to Palestine and land purchase were essential to create a demographic and geographic nucleus for Israel to be established. Essential for Zionist land purchase was the willingness of Arabs living inside and outside of Palestine to sell lands to Jewish buyers. No Jewish state could have come into being without Arab land sales. Arab leaders, the Arab press in Palestine during the Mandate, British officials, Zionists, and respected commissions of inquiry that rigorously investigated the underlying reasons for communal unrest and prolonged violence during the Mandate all agreed that Arab land sales to Jews were a core reason for Zionism’s success.

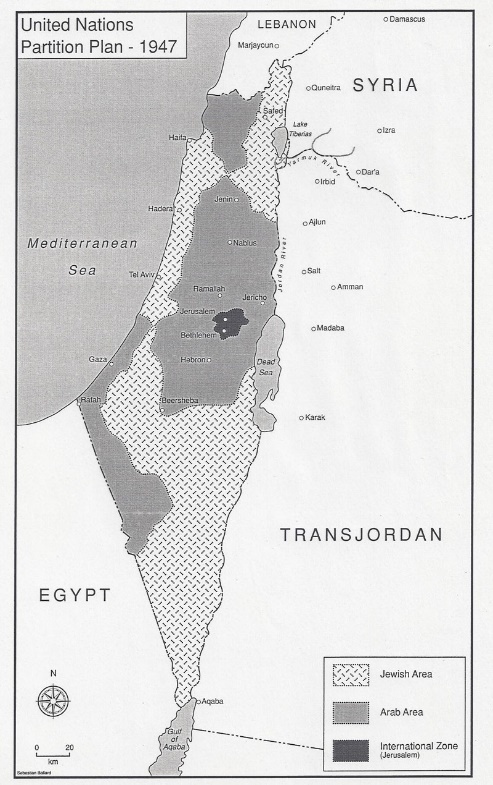

The 1947 U.N. partition plan assigned Jews 14,100 square kilometers (5,400 square miles), while the Arabs were allotted 11,500 square kilometers (4,400 square miles). The remaining area, covering Jerusalem and its surroundings, was designated as an international zone. The Jewish Agency, representing Jews in Palestine, accepted the partition plan, while the Palestinian leadership and Arab states rejected the idea of partition and with it a Jewish state. When the 1947-1949 war ended, the nakbah — the disaster in Arab historiography — Israel was left in control of 20,770 square kilometers, an increase of 47% from what the 1947 U.N. plan allocated to the Jewish state. The remaining areas of what had been the Palestine Mandate, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, were controlled by Egypt and Jordan, respectively, until the June 1967 war. Neither Jordan nor Egypt nor Arab states in general made any effort to establish a Palestinian Arab state or entity in these two areas. Their position was clear and united: The Arabs would not share the land west of the Jordan River with a Jewish state.

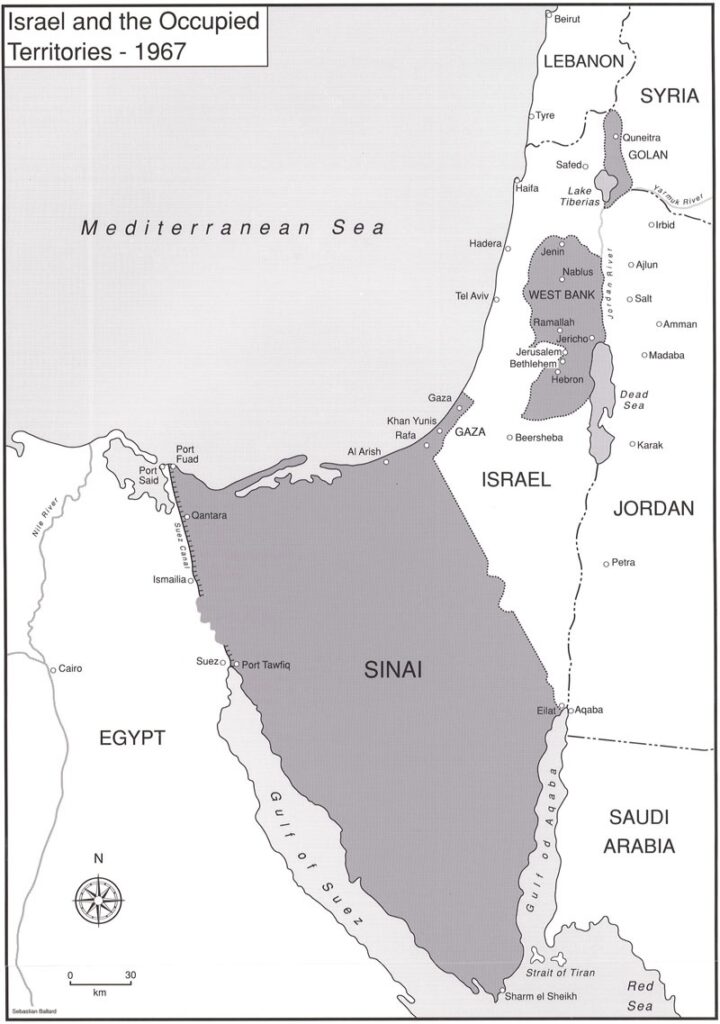

After the June 1967 war, Israel controlled those two areas, as well as the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, the Syrian Golan Heights, and the portion of Jerusalem that Jordan had held since 1948. With these new areas Israel covered some 88,000 square kilometers, more than quadrupling the state’s size.

As a result of the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli treaty, Israel returned all of Sinai (some 61,000 square kilometers) to Egyptian sovereignty.

In 2005, in a unilateral action promised by Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, Israel withdrew from the 365-square-kilometer Gaza Strip, turning it over to the Palestinian Authority. Hamas, which won legislative elections in 2006, seized control of the Gaza Strip from the PA in a coup d’etat in 2007.

The Syrian Golan Heights, some 1,200 square kilometers, have remained occupied, administered and controlled by Israel since the June 1967 war. In July 1974, President Richard Nixon promised Syrian President Hafez al-Assad that the Golan Heights would be returned to Syrian sovereignty. But in September 1975, President Gerald Ford told Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin that the U.S. “would give great weight to Israel remaining on the Golan Heights in a peace treaty with Syria.” Israel annexed the Golan Heights in 1981, and President Donald Trump in March 2019 recognized that annexation, something Syria and other Arab states strongly opposed. Upon the end of Syria’s Assad regime in December 2024, Israel occupied portions of that country adjacent to the Golan Heights, citing security reasons.

The constant debate over the West Bank — how many settlers, how many settlements, what constitutes a settlement, how much control the PA has over certain areas — makes it impossible now to assign exact amounts of the land in what is also called Judea and Samaria to Israel or Palestine.

As for the portions of Jerusalem that Israel secured in June 1967, some 6 square kilometers, Israel formally made them part of a greater Jerusalem municipality in a 1980 Israeli Basic Law. All Arab states and the PLO vehemently opposed that annexation.

— Ken Stein, June 30, 2025