Tal Grinfas-David

Newsworthy stories unfold in Israel at breathtaking rates. Repeated elections, COVID-19 responses, path-breaking Supreme Court decisions, the Abraham Accords — all are worthy of community discussion and age-appropriate student exploration. Yet few Jewish students and their parents possess sufficient understanding or discussion skills to explain them beyond a passing headline.

These rich topics relate to peoplehood, democracy, and the Land and State of Israel. They affect our Jewish identity and Israel’s role in it. We all could use a booster shot in our knowledge foundation. We realize that knowing core information, let alone the associated nuances, requires time, specifically educational foundations that can’t be packed into a few hours a week of Judaic studies in a post-b’nai mitzvah class or in 11th or 12th grade.

Four years working closely with a dozen schools across North America have shown me the wonderful benefits and experiences from comprehensive and integrated approaches to Israel education for students, parents and the community at large. The positive results from the Center for Israel Education’s Day School Initiative are replicable. These are three of the most important lessons learned.

• Start early and often.

We do not teach calculus in kindergarten, nor do we avoid grade-level benchmarks for fear that students will hate math. We also do not let each educator decide how and when to teach elements of math. Instead, we use a well-defined curriculum to help children acquire difficult foundational concepts and skills bit by bit, year by year.

Similarly, we shouldn’t expect 11th-graders to grapple with Israeli-Palestinian relations, Israel’s parliamentary democracy, its management of a pandemic or the debate over religion in Israel’s Jewish identity without a foundation of age-appropriate Israel education. We need to educate from the earliest grades upward. By developing a knowledge base, a connection and a habit of informed conversation from an early age, we make possible the later discussions that we desire and for which students hunger.

An example is Jack M. Barrack Hebrew Academy in Bryn Mawr, Pa., which is building depth and sophistication into Israel education for its sixth- to 12th-graders. A three-part series for 10th-graders, for example, builds on earlier lessons to address Jewish diversity and the compromises involved in maintaining peoplehood. Such learning leads to questions about the diaspora origins of Israeli democracy and how Israeli and American Jews influence each other.

• Integrate Israel throughout the curriculum.

As the National Council of Teachers of English noted in 1995, the world is not organized into distinct subject areas, and a curriculum should reflect that complexity. If schools are serious about mission statements citing Israel education as central to Jewish identity, they should treat Israel education as equal to other subjects and incorporate it into everyday general studies. Israel can’t be an afterthought granted a sliver of the time set aside for Judaic studies, with some extra time allotted weeks before a trip to Israel.

When Israel is integrated into science, math, English and social studies, the subject belongs to the entire faculty, and educational silos are toppled. Educator collaboration increases, which improves staff morale and the school climate.

Students perceive Israel as a subject that matters and gain the proven benefits of interdisciplinary instruction, including critical thinking, problem solving and an appreciation for uncertainty.

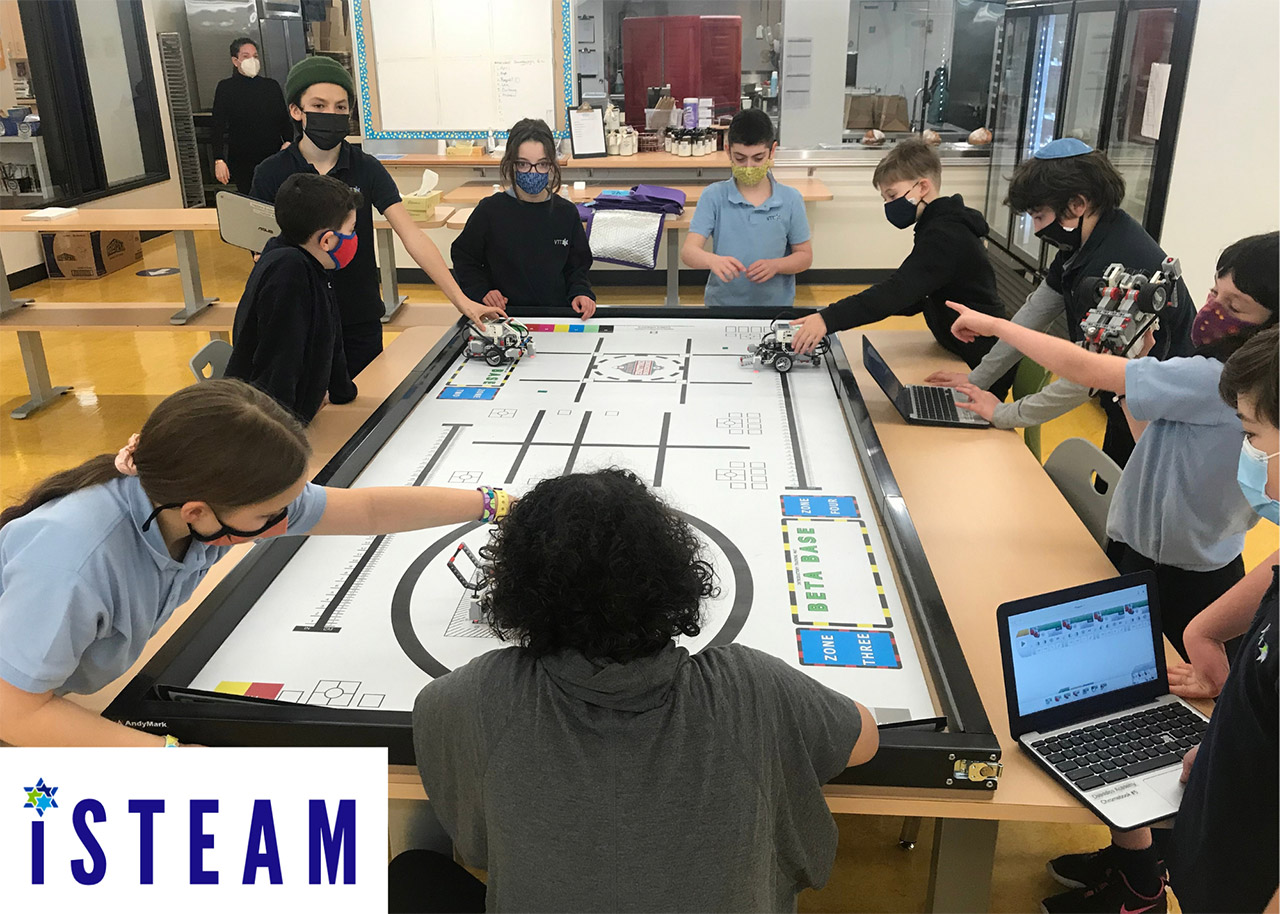

Vancouver Talmud Torah in British Columbia has created an integrated curriculum called I-S.T.E.A.M. (Israel through Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Math). In one study unit, students explored Israeli architecture and watched videos of such designers as Eliezer Armon and Yaakov Agam. They took virtual tours of Israel to learn what makes spaces holy and how to bring that special feeling to places in their lives. They combined those inspirations with engineering lessons about form and function and computer skills in design software to create a plan for a new school wing, then wrote essays to persuade administrators to accept their design.

• Involve the community.

Far from sparking controversy, well-integrated Israel education based on original sources generates critical thinking. Biases and polemics cannot take root when sources are used and interpreted.

Bringing communal influencers into the process builds trust and helps deepen the community’s Israel discourse.

Parents become key supporters when their excited children bring home new knowledge and when schools invite them to participate. While only anecdotal, evidence suggests that these schools retain students and boost enrollment.

Sinai Akiba Academy in Los Angeles has recognized the crucial part parents can play in middle school. While writing lessons and experimenting with activities for students, the administration and teachers are also designing opportunities for parents to learn. The programs will showcase informed discourse and build bridges among families with diverse opinions.

We have learned that instituting excellent Israel education requires a multiyear commitment. I meet with some teachers weekly to review lesson plans, demonstrate presentations to students, and help them wring out biases and assumptions for or against Israel and commit to primary sources over preferred narratives.

The payoff is immense.

In the short term, teachers find their work more rewarding. Students are excited and engaged. Parents learn and become more committed to the school community.

In the long term, deep knowledge of Israel’s history, politics, economy and culture, rather than idealized portrayals that can be shattered, leads to understanding of why Israel matters to Diaspora Jews and can make Israel a community unifier instead of a divider.

That unity goes beyond Israel. While examining debates ranging from the Zionist Uganda Plan to the sinking of the Altalena to contemporary politics, schools are modeling listening, speaking and disagreeing according to Jewish values. Just as in every generation the Jewish people have struggled with the dreams and realities of Israel, so too we have managed to embrace the strengths and weaknesses of our differences, then compromise and come together.

When we have those substantive Israel conversations with our students, we empower them to connect and stay connected with Israel and to be agents of change and continuity in our Jewish communities.

Dr. Tal Grinfas-David is CIE Vice-President for Outreach and Pre-collegiate school management.