May 9, 1977

Source: FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1977–1980, VOLUME VIII, ARAB-ISRAELI DISPUTE, JANUARY 1977–AUGUST 1978, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1977-80v08/d32

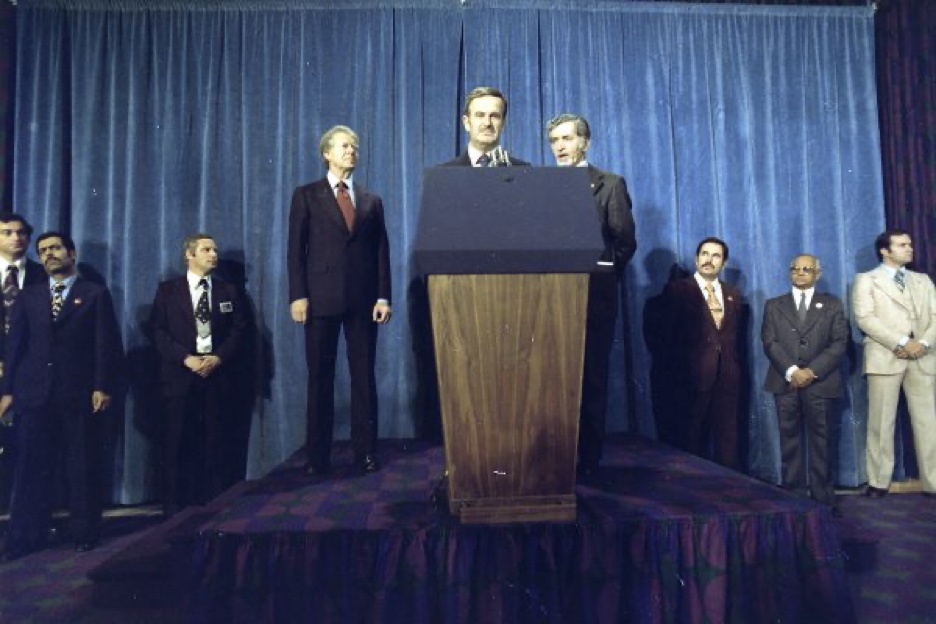

Consistent with the Carter administration policy of “fact finding” with Middle Eastern leaders during its first year in office, President Jimmy Carter met with President Hafez al-Assad at a Geneva hotel in May 1977. Assad did not want to meet Carter in the United States. Though the administration had come to office with a dogged determination to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict in a comprehensive fashion, Carter’s leadership team of Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski and Carter himself knew little about the unique political cultures and attitudes or how deeply protective each country and the PLO were about not placing their national interests into the hands of even a trusted mediator such as the United States.

The Carter administration had decided to resolve the most outstandingly difficult conflict in the world at the time (if one excludes the Cold War) in a comprehensive manner at a conference, without first fully comprehending the historical and ideological complexities of each Arab country, the PLO or Israel. Pre-negotiations to a comprehensive resolution of the conflict did not take place between parties to the conflict. Rather, pre-negotiations to resolve differences took place between the mediator and individual parties to the conflict.

This meeting was the only in-person meeting that Carter had with Assad during the Carter presidency. Carter wanted to learn what Assad’s requirements were for an agreement with Israel: borders, security, nature of peace and willingness of other Arabs join. Assad doubted that the Saudis would join any negotiation process. When the conversation was finished, Assad made it clear that he was not rushing into an agreement with Israel, even if asked by the United States. Carter acknowledged to Assad that he knew little about the Palestinian refugee issue, saying, “I have not studied it.”

Assad did not say that participation of the Soviet Union at a conference was necessary; in fact, he noted how difficult his relations were with Moscow in the immediate past. Assad did tell Carter that it was Secretary of State Vance who first raised the possibility of Moscow attending such a peace conference. From American diplomatic sources we learn that Assad was incredibly pleased to have been squired by Carter. For their part, the Israelis were quite anxious about Carter’s positive statements about having this meeting with Assad.

Carter told Assad that the United States was committed to the security of Israel, so therefore in Assad’s views what should be the guarantees for peace and security? Assad spoke of ending belligerency before moving on to “peace.” Assad had wide-ranging reservations about reaching an agreement with Israel. He sought an Israeli return to the 1947 U.N. Palestine partition lines, the return of lands Israel had won in the 1967 war and a resolution of the Palestinian refugee issue.

Assad was clear. He did not accept Israel’s existence; he saw Israel as aggressive and expansionistic. On the Palestinians, for him there was no way to solve the problem except to go back to the U.N. resolutions (181 and 194) and restore Palestinian rights. He noted the political distance between Jordan and the PLO. He offered that he did not believe that the PLO would accept Israel or U.N. Resolution 242 before a Geneva conference.

About Israel, Assad he made these points:

- “If we were being logical, if this were a legal deliberation, we would consider that Israel should not be in the United Nations, since it has not lived up to the condition of conducting its commitments. Not only has Israel not observed Resolutions 181 and 194, but also it has encroached on and occupied more and more territories than those allotted to it originally.”

- “Israel is basing all of its actions on the premise that it will not leave the territories occupied in 1967. They are saying and emphasizing that the borders will be defined by where the Jews live.”

- “We cannot understand how U.S. Jews could permit themselves to take unfair advantage of their country’s interests for the sake of Israel.”

- “I, as a Syrian citizen, cannot imagine that any leader in Syria or any other Arab country could agree to give up any territory.”

- “When Israel talks of secure borders, we understand that they want more territory, not just international forces, but territory.”

Though Carter had heard firsthand from Assad his refusal to negotiate with Israel, the administration nonetheless remained undeterred and still traveled along the path of seeking a comprehensive Middle East peace conference where all states, the PLO and Israel would attend. He would learn in the summer of 1977 that the PLO would not recognize Israel, and still the administration stubbornly held fast to convening a Middle East peace conference.

— Ken Stein, March 18, 2023

Memorandum of Conversation Between President Carter and President Assad

9 May 1977

Geneva, 3:50–7 p.m.

PARTICIPANTS:

President

Secretary of State Cyrus Vance

Dr. Zbigniew Brzezinski

Assistant Secretary of State, Alfred L. Atherton, Jr.

Ambassador Richard Murphy

Mr. Hamilton Jordan

Mr. William B. Quandt, NSC Staff

Mr. Issa Sabbagh, Interpreter

President Hafiz al-Asad of Syria

Foreign Minister Abd al-Halim Khaddam

Adib al-Daoudy, Political Adviser

Abdallah al-Khani, Deputy Foreign Minister

Ambassador Sabah Qabbani

Assad Ilyas

President: May I outline some of my thoughts first, and then perhaps ask you some questions?

President Asad: Yes, please.

President: We are very eager this year to see progress made in the Middle East and I will be devoting a great deal of effort to learn what we might do. We don’t want to interfere, but we will contribute our good offices if needed. Our constructive effort can only be significant to the extent that all nations involved trust us to be fair and to be truthful and to try to be sensitive to the deep feelings of the people in the region. I don’t have any preconceived ideas, but I am eager to learn from you your own thoughts on the possibilities of agreement. I have met with Prime Minister Rabin, President Sadat, King Hussein, and after the Israeli elections, I will probably meet their new leader. Crown Prince Fahd will come to Washington later this month. We will try to search out common ground for an agreement, and then we will come back and talk in a quiet way to all of the parties, with Secretary Vance again visiting the Middle East countries. If there seems to be a prospect for progress at that time, we would take your advice on how to proceed. My thought is that unless substantive agreement seems possible, it might be better not to have a conference now. (President Asad nods agreement.) But if we do not make progress this year, a conference might be far off in the future. I will not be timid about my own leadership in bringing the countries together if you think our strength and influence will be beneficial. I know there are some issues on which countries cannot change their positions, but we hope that each country will be flexible where possible.

We need your advice on many questions—the participation of the PLO, the move toward recognized borders, the definition of what peace means, how rapidly the terms of agreement might be carried out, the degree of participation by the Soviet Union, and what guarantees by other nations of the peace agreement might be advisable if we reach agreement. I would like to have you discuss these matters this afternoon and if you permit, I would like to ask you questions about what you think.

President Asad: We are bound to have some questions. Once again I would like to express my thanks to President Carter for his efforts and for coming to this meeting. As you were talking, my mind was working on how I can best start. No doubt the problem is complicated. No matter how hard we try not to repeat things that have already been said, it is inevitable that we will repeat—I am not talking about you, but more generally—we will repeat things that have been said in my talks with Secretary Vance and others.

President: Maybe this will be the last year we will have to go over this ground. (Laughter.)

President Asad: But I hope this will not be our last meeting. In any case, if someone thinks we need problems in order to keep on meeting, we can always create some. (Laughter.) I want to be as brief as possible. I might say that the problem in our area began with the occupation of Palestine by the Jews. Don’t worry, I am not going to go into the whole history, it is too long. I might even put it another way. Our area has been subdivided into many different countries. And I wish that President Carter could study in depth the history of the whole area, and not just of Palestine.

President: I did today.

President Asad: Our countries were subdivided into small states under colonialism. I don’t want to deal with the whole Arab world and I will confine myself just to Syria. Up to a certain point, there were no separate states of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan. They were all one. We are talking of the era of colonialism, of French and British rule. Presently we have good relations with both countries, but this is something they did in the past when they were colonialists. The British took Palestine and Jordan . . .

President: And Iraq.

President Asad: And the French took Syria and Lebanon. This was done irrespective of what bound the people of the area together. Suppose the colonial powers wanted a connection between the Mediterranean and the Gulf. They would just draw a line, which might divide people, tribes, etc. Of course, present-day Syria was subdivided into five sections, but, at the first chance we had to regroup, we did so. We see that in the long run to subdivide countries does not serve the people or the countries themselves. This haphazard subdivision was the prelude to the creation of Palestine. This subdivision has led to problems that we recently saw in Lebanon, and I don’t know what else might come in the future. This is not the crux of the matter now, but I meant this as a prelude since this is our first meeting.

President: That’s very helpful.

President Asad: I would like to refer to the historical background for another major reason. When in the 1940s the Jews occupied Palestine, you all know what happened—there was fighting, the UN was summoned, there were UN Resolutions—you know the whole story. As a result of these deliberations, Israel was accepted as a member of the UN, but the acceptance of Israel, in my opinion, was unique. No other state was accepted into the UN with the qualification that it accept two UN Resolutions—one of these dealt with the division of Palestine, and the other dealt with the right of return of refugees to Palestine. I believe 194 dealt with return, and 181 with partition.2 The resolution by the General Assembly accepting Israel into the United Nations was based on the fact that Israel had already accepted Resolution 194 on the return of refugees. The representative of Israel at the time was Abba Eban, and in the light of the commitment that he gave, Israel was accepted into the United Nations.3 If we were being logical, if this were a legal deliberation, we would consider that Israel should not be in the United Nations, since it has not lived up to the condition of carrying out its commitments. Not only has Israel not carried out Resolutions 181 and 194, but also it has encroached on and occupied more and more territories than those allotted to it originally. In the 1948 Armistice Agreement,4 there were areas that were to be demilitarized zones—in Arabic, we call these forbidden territories. There were other areas where the Arabs could have their own forces. These areas Israel nibbled away at, expelling the Arab inhabitants. This was not the result of war, but rather of daily clashes, to the point where Israel occupied all of these areas and expelled all of their inhabitants. All of this took place before 1967 and was the result of daily fights.

Behind these demilitarized zones on both sides—and before I left Damascus, I thought of bringing a bas-relief map, but I did not do so because of the time, but when you visit Syria, you can study the situation on the spot, and it will give a clearer picture. Behind these demilitarized zones, there were some lightly defended areas where there could be no tanks, etc., and no guns of a certain calibre. On the Syrian side, these were about six kilometers in depth, and on the Israeli side about twelve kilometers. To all of this, Israel turned a blind eye before 1967.

In 1967, Israel occupied vast territories and in 1967 Israel’s expansionist intentions were seen with utmost clarity. As I recall, Defense Minister Dayan gave a speech to the Israeli armed forces—he was then known as a great military hero—and in his first speech he said that the previous generation had realized the 1948 borders, that he had brought about the Israel of 1967, and that now the next generation would bring about greater Israel. Even if we assume that he said this out of an intoxication brought about by victory, it is still of some significance. Of course, Israel is basing all of its actions on the premise that it will not leave the territories occupied in 1967. They are saying and emphasizing that the borders will be defined by where the Jews live.

Of course, when we say Jews, we don’t mean those members of a religion that we respect. In our country, we cannot be religious bigots. This is well known and there are reasons for this. The first, divine religions were born in our backyard—Christianity and Islam. Jesus Christ Himself was a Syrian—before partition! Even today, in some tribes one finds both Christians and Muslims. Of course, I say this as historical background on why we cannot be bigots. Christians and Muslims are mingled and in my country, you cannot tell any difference between a Christian and Muslim Syrian. And this is true of Syrian Jews, although our attitude to them has been colored since Israel’s creation. But we have a Jewish Religious Council to adjudicate matters in Syria, which plays the same role as the Mufti. During my time in office in 1971, I met with the heads of the Syrian Jewish Community. I discussed their problems. At that time, representatives of the Jews discussed subjects involving Jews who had been convicted of smuggling money out of the country—this was also the case for some non-Jews—and after the discussion I immediately pardoned some of those convicted. I have done other similar things. During those discussions in 1971, I talked of the spiritual values that bound us together, but I said that I could not agree to consider them as citizens of Israel. They are Syrians of Jewish faith, just like Syrian Christians and others. Of course, as events have proved, Syrian Jews have been very angry with Israel since Israel has brought them no good at all. I would like to repeat that we are not against Jews in any part of the world, but we want them to be citizens of their own country. Syrian Jews should be Syrian citizens, and US Jews should be US citizens, loyal to their own country.

We cannot understand how US Jews could permit themselves to take unfair advantage of their country’s interests for the sake of Israel. We all have a general commitment to humanity at large, and I have talked of this with some American Jewish leaders. After 1967, Israel continued to design and to build its future on the basis of occupation of the territories. It kept on setting up settlements, villages, industrial complexes, agricultural projects, moving people to new settlements, tearing down old settlements, and putting up new ones. They indicated the permanency of their tenure there. That was already understood from their statements but it was confirmed by their tangible actions. There were efforts between 1967 and 1973 at the United Nations, by the four great powers and others to see what could be done. There were some African efforts. Once there was a committee of ten which chose four representatives to go to Israel. President Senghor, who is a good man, was part of this. He went to Israel at a time when they had good relations and they started with the impression that the Arabs were the aggressors and were the recalcitrant party, so they went to Israel. But they came back with different convictions. They had no idea that Israel would refuse to withdraw and they came back with the conclusion that Israel wants to stay in the territories.

There was an American project, the Rogers Plan,5 which Egypt agreed to [sic], but all of these efforts went by the wayside. There is no doubt that Israel caused all of these efforts to fail. Without a doubt, these were serious efforts. With good will, they would have had a chance of success. Perhaps if some were not serious, others were, up until 1973. The ceasefire was brought about in 1973 by UN Resolution 338. We in Syria delayed our acceptance of the ceasefire resolution. The resolution was voted on October 22, and we delayed until October 24. In the written acceptance that we gave, we accepted Resolution 338 on the basis that Israel would withdraw from the territories and would restore Palestinian rights. As is well known, before Resolution 338, we did not accept Resolution 242. Actually, we did not accept 242, but in the midst of all of the turmoil, and with Resolution 338, we gave our written acceptance, but it was conditional on withdrawal and the restoration of Palestinian rights. At that time, we wanted this to be clearly understood. We did not want anyone to come and say we had accepted Resolution 242 by implication. The same day, Israel said that Syria does not accept Resolution 338 because of the conditions attached. Because of military complications caused by the exiting of Egyptian forces from battle at that time, we had to accept. Israel got lots of support, so that they again felt that they could flex their military muscle. But I think that it would have been better if the war had gone on. This was my opinion at the time, but we are now talking of peace.

My remarks are not meant to belittle Israeli military prowess, but there were other factors that would have helped if the fighting had continued. President Carter earlier mentioned to me my talks with Henry Kissinger. In 1973 everyone believed that the war was over, that the Geneva Conference would begin and everything would be fine, and the maximum period needed to succeed was thought to be six months. President Sadat sent me a message on October 24, before the ceasefire. He sent it with Prime Minister Aziz Sidqi. He said that we may as well accept the ceasefire, since there will be a peace agreement in no time at all. The countries that were in contact with each other gave that impression. Now months, and even years later, this has not come about. What are the elements in the situation now?

Our understanding of the basic elements is the same as yours. There are three basic issues which I have reviewed with Secretary Vance and which President Carter’s statements have covered also. The first is borders or the occupied territories. The second is Palestinian rights. The third are the prerequisites for peace. In general, our attitude is . . . Before I give our attitude on these three elements, I should say that in Syria, and in the Arab world, we have shown flexibility not dreamed of by others. Before 1971, we did not talk of peace. This is not because we are the enemies of peace—Syria and the Arabs cannot be—but because of our conviction that Israel would never want peace. Notwithstanding that popular sentiment, we started talking of peace. Israel said that the Arabs don’t talk of peace, only of war. When the Arabs talked of peace, then Israel talked of negotiations. Then when the Arabs came around to talk of negotiations, Israel took another step. They are creating more obstacles to progress. As I told Secretary Vance in Damascus,6 if Israel keeps leap-frogging this way, Israel may soon insist on choosing who the Syrian Ambassador will be to Israel. I say this because Secretary Vance was asking us about the exchange of diplomatic relations. There has been flexibility, in other words, in our attitude, but Israel should not be given to understand that flexibility means giving up on crucial points. We will be flexible in our tactics, and on how things are done. Now, let me go back to our attitude on the land occupied in 1967.

I, as a Syrian citizen, cannot imagine that any leader in Syria or any other Arab country could agree to give up any territory. For two parties to fight and have one lose is one thing, but it is different to agree to have mutual goodwill and to look for peace as a mutual objective. Here we are talking of security in our area. We are not talking of a vanquished party and of a victor. But if people insist on these considerations as being inevitable, then we will consider ourselves the victor in the 1973 war. It is natural when we talk of our fate as Arabs, of the question of occupied lands, and of a people that has been dispersed, that we look at all eventualities. What would future animosity bring? I, as an Arab citizen, can only conclude that the future is on my side if the struggle continues, especially since the just cause is on my side and Israel is the aggressor. Nevertheless, after we had concluded that time is on our side, we are bound to reflect on why we should allow all of these years to pass and all of the blood to be shed. Why not talk of peace now? From this view, we want peace, but why should we end the animosity if I am going to have to lose something. This would be a brake on my enthusiasm for peace, even if I could give up anything. If I gave up territory, would I serve any principle? Would I serve the Syrian people or humanity, or the Syrian interests that I represent? Then why should I do it? What is in it for me? The answer may be to end fighting and military operations, but to this I say that if the aggressor finds that it is not futile to bear these costs, why should we not also put up with sacrifices?

Israel’s pretext for keeping the 1967 occupied territories is that of secure boundaries. I recall in 1974 receiving a delegation of the International Socialists, including Chancellor Kriesky. I was visited by them, and we discussed the subject. I asked the British Labor representative to talk. He had been sitting there like a sphinx until then. I asked him to speak first because we all know of the British role in the problem. He was from a country which had suggested Resolution 242. I asked his view on secure borders. At the end of the discussion, the British representative said that Israel’s view has nothing to do with Resolution 242. They just want to keep the territories, not for security reasons but because they are good territory. He told us this, although I do not know if he told it back home as well.

Secure boundaries are non-existent. We cannot talk of imponderables. I will give two specific examples. In 1967, Israel occupied the Sinai and Golan. In Sinai, there are those passes that are supposed to help whoever occupies them. Israel took them and there was no obstacle in the path of the Israeli forces. In the Syrian Golan, our forces were there and yet we could not prevent Israeli occupation of Golan. Holding the territory did not by itself present an obstacle to the invader. In 1973, Suez was not a secure border for Israel. Egyptian forces crossed the Canal and took territory. The Israelis on their side made a counter-offensive. On the Golan, we got as far as the edge of the Heights, down to the river, and all of the hills and fortifications did not stop us. We went back for other reasons, but we reached the edge of the Heights. Golan did not provide Israel with secure borders. It goes without saying that even in the past there has been nothing that can be described truly as a secure border, especially in the era of modern weapons. This idea does not exist at all, when we have modern guns, rockets, airplanes and tanks. In the face of these weapons, there are no secure borders.

I have given examples from the October war and from the 1967 war. When Secretary Vance is in Syria next time, he may visit some places on the ground. He will see the observation position on Mt. Hermon. It was heavily fortified, but we liberated it in the first hours of the October war. It is man who moves forward or back. Nothing can be called a secure border. Why does Israel want secure borders in Golan, and not in Galilee? Golan, as you know, is a hill.

President: I have been there in 1973.

President Asad: Have you seen Galilee also? Do you have a clear picture?

President: Yes.

President Asad: There is a valley between Golan and Galilee.

President: I have been up on the Golan.

President Asad: As you stand on the Galilee mountains, you look down on the Golan Heights. Galilee is higher. It has more complicated terrain. It is more easily fortified and is suitable for defense lines and would not require the expelling of inhabitants from any territory. The areas that I spoke of before as demilitarized zones before 1967 are in the valley. These were taken by Israel before 1967.

If we agree to the theory of secure borders, which may be a just consideration by itself, it would have to be the right of all countries. If we agree in principle, then we would have to give each country the right to take territory from others. Israel would take some territory from Syria, Syria would take some from Turkey, Canada might take some from the United States, and so on. The whole world would become a jungle. It is strange to insist on secure borders on other people’s territory. It would mean that they want more land, not just defense. There are other indications that they want more land, not security. They used to say that Syria attacked their settlements, but in 1967 when they took Golan, it did not prevent us from being able to shell their settlements, even though our troops were back further. The depth of the Golan Heights varies between 14 and 26 kilometers. The area is only 1,200 square kilometers. Long-range guns can go further than these distances. It is not essential to be able to see one’s target to hit it. They say that they pushed us back for security purposes, but this is not true. Suppose that we did say all right, that this was done to secure their own settlements, but then why did they build new settlements, some of which are only 300 meters from our territory? Why did they push us back and then invite our artillery again by having settlements established within artillery range? Now to protect these new settlements, they will need to establish even more, and so on. But we don’t have much more to give! We are bound to ask why should secure borders be 50 kilometers from Damascus, but 350 kilometers from Tel Aviv. I asked Henry Kissinger about this. He said that they could change their capital to Haifa, but I replied that in that case we would move ours to Quneitra. In essence, to talk of secure borders does not rest on anything real. Shall we go on to talk about the rights of the Palestinians, or do you have some questions?

President: I have lots of questions, but I don’t have any answers yet. I think the question of secure borders is important, not just for you and for Israel, but for the rest of the world as well. If you and Israel desire, perhaps we can help, along with others, to guarantee those borders to prevent eventual bloodshed. This is what we want. The area that would be used to secure the borders would have to be determined—its depth, and perhaps some demilitarized zones, or peacekeeping forces from other countries. But these are decisions for you to make. Unless it can be done, the conflict will continue, and perhaps you will ultimately win, no one knows for sure. But we have no desire to impose our will on you or Israel. If the decision can be reached that the pre-1967 borders are the proper ones, then to guarantee those borders would be a great step forward. This may not be the desire of Israel either, but we would try to pursue your wishes with the Israeli leaders, if it seems fair and with prospects for a permanent arrangement.

President Asad: When Israel talks of secure borders, we understand that they want more territory, not just international forces, but territory. This is different from what you said, Mr. President. If they are after more territory, they will want to put the forces there.

President: We don’t see it that way. Any forces placed there would be those that you wish. These could be from any nations, including ours.

President Asad: I understand that you want a reply on this.

President: I’ll wait, I cannot speak for Israel, but this is my understanding.

President Asad: I am more concerned about your views. Israel wants Damascus! Concerning the 1967 boundary, we would agree to areas being demilitarized on both sides. Especially since you have seen the terrain, you know that it does not permit in-depth areas of demilitarization. The territory is inhabited, there is arable land, and even the land that is not cultivated could be. If it would be helpful to have an international observer force, provided that it is not a huge army, we would agree.

President: May I ask a question? How do you feel about observer posts, if these were desirable?

President Asad: When we talk of Golan, it is possible to see everywhere with only a pair of binoculars. In fact, Minister Khaddam talked with Secretary Vance about this. If we are convinced of the efficacy of these arrangements, we would readily say all right. But the distances are short, and you can see quite easily. It is very different from Sinai where there are vast distances. It is only 50 kilometers to Damascus, so these ideas are not very practicable. In fact, the other things that you mentioned are more effective.

President: But is it a possibility?

President Asad: In addition, I have heard that the Sinai observer posts can even watch Golan. When Secretary Vance goes to the area, he will be able to see how easy it is to see everything with only binoculars.

President: But would observation posts be a possibility?

President Asad: I’m a pilot, now retired, and as far as I know, these posts, including radar and other things, are not necessary. They would not perform the functions required.

President: But I want to keep the option open, even though I am not asking for your commitment.

President Asad: If I am convinced that there is a necessity for these, then I would say OK. There is a reason for our stand. Damascus is very close to the front lines.

President: Would you object if other Arab countries took a different position on their borders from what you do on the Golan Heights?

President Asad: No. No.

President: What kind of guarantee of the borders and of the peace settlement would be most acceptable to you?

President Asad: Demilitarized zones, and if necessary, forces in those zones, and an ending of the state of belligerency. These are the maximum possible and the maximum necessary.

President: Concerning the forces in the demilitarized zones, do you have any preference on their nationality?

President Asad: We have no objection, as long as these are under the over-all umbrella of the United Nations. As for which countries, there might be some like South Africa or Rhodesia, or Israel, that would not be so good.

President: Israel is a member of the United Nations. I thought you might prefer them. (Laughter.)

Secretary Vance: Would it be useful to have a Security Council guarantee of the peace agreement?

President Asad: This would be good and useful. But I do not see it as a necessity, but only as a useful luxury.

President: Do you have any objection to American or Soviet forces?

President Asad: Where?

President: In the demilitarized zones.

President Asad: When the time comes, we’ll see.

President: OK. Let’s talk about the Palestinians.

Secretary Vance: All of these issues are interlinked.

President Asad: On the Palestinians, there is no way to solve the problem except to go back to the UN Resolutions and to restore Palestinian rights. There are two facets of the problem: First, the question of Palestinian territory occupied in 1967; second, the question of Palestinian refugees. Some have perhaps not made this distinction. Everyone is talking about a Palestinian state which would be on the West Bank and in Gaza. (President leaves briefly, and discussion begins on question of Syrian Jews.)

The condition of Jews in Syria has improved, and we have been able to sort out some problems. We have approached this from a humanitarian point of view. When Congressman Solarz visited, we had a good talk with him,7 but we told him that the basis for our discussion was a humanitarian concern and that we could not consider him a representative of Syrian Jews. It is our attitude that those Syrian Jews who have relatives in the United States can leave Syria to visit them. Their situation has improved. But because of the current situation where Syria and Israel are enemies, we cannot allow them to go to Israel. It is all right for them to emigrate to the United States and if you can assure us that they will not go to Israel, we would have no problem. As I say, we view this from a humanitarian standpoint. (The President returns during the latter part of this discussion.)

President: If we were to provide information on a couple that wanted to get married, would it be all right for the woman to come to the United States?

President Asad: Yes. We would deal with each of these cases on its own merits, since it is of interest to President Carter.

On the Palestinians, as I said, many people have talked of a West Bank and Gaza state, but I cannot see how it would accommodate all of the Palestinians, even assuming that the Palestinians would agree to it. As part of the solution of the problem of Palestinian rights, I see that there are two issues—the Palestinian state and the problem of the refugees. If there is no solution to the refugee problem, it would remain complicated. A hostile attitude would still exist among the refugees, so these are the two elements of the question. The Resolutions of the United Nations are very clear on this subject. These are the same resolutions that I mentioned previously: the right of return or of compensation. As to the Palestinian territories occupied in 1967, that would be dealt with as part of the withdrawal question. The Palestinians are flexible and they are seeking a solution in earnest. They want a solution, corresponding with their aspirations. They emphasize the matter of refugees. Only the day before yesterday, I saw Arafat at his request and we had a discussion along these lines. So the problem of the refugees for the PLO is still a big problem. This is the essence of how I see the Palestinian problem. The territories occupied in 1967 and the refugee issue both have to be resolved and Israel opposes the solution of both of them. A suitable solution must be found.

President: Do you see the West Bank and Gaza as adequate for the refugees?

President Asad: No, this is what I said before. There are only 6,000 square kilometers, 5000 on the West Bank, and 1000 in Gaza. This is not enough. In spite of the fact that all Palestinians underscore the point of a Palestinian state and that they are clamoring for it, I am trying to see the whole picture. Any solution of the Palestinian problem, without settling the refugee part, would be incomplete.

President: To see the Palestinian question in specific terms, concerning the refugees, and recognizing the need for Israeli agreement, how do you see a practical solution? I don’t believe that Israel can agree to take all of the Palestinians into their territory. What does Arafat have in mind that is practical?

President Asad: Of course, what would be practical and idealistic would be to go back to the UN Resolutions. But to say that the refugees would go back to a Palestinian state of only 6,000 square kilometers, I wonder if that is enough to absorb all of them. That is the question. But for the refugees to stay in other states, this is also an illogical solution. In Lebanon, for example, they would find it hard to keep the Palestinians there and it would be hard for Palestinians themselves to remain. So the problem is evidently not a simple one. Why would Israel not accept the return of the refugees?

President: How many?

President Asad: I am sure that not all would want to go back.

President: I don’t have any idea of this.

President Asad: It is very difficult to give a figure, or to even know who is a refugee, since they are so dispersed. (President Asad and Foreign Minister Khaddam discuss among themselves how many Palestinians there are in various countries.) We have not discussed this in any detail before.

President: I am trying to seek a solution to this. This is the first time it’s been raised.

President Asad: I know.

President: I don’t think it is likely that Israel will let in hundreds of thousands of Palestinians into their small country. I hate to leave this unanswered. You are the one who can help me with it.

President Asad: I am anxious to provide you with a reply, but I don’t want to mislead you. We estimate that there are about 2,000,000 Palestinians outside of Palestine now.

President: It will not be possible for anyone to get all that they want.

President Asad: I agree. But this is the first time we have gotten into this kind of detail.

President: Only Syria is likely to get all that it wants! (Laughter.)

President Asad: Concerning the principles of a settlement, we have to adhere to UN Resolutions on return or compensation. But when something is put on the table, then we will be better equipped to deal with it. We could discuss this in more detail and with more persuasion.

President: Can Arafat speak for the Palestinians?

President Asad: He needs some help from all of us. We all must help him.

President: I understand.

President Asad: There exists disagreement among the Palestinians, but we might help, and the Egyptians. But there will still be some problems. But in a case like this, they are not unsurmountable.

President: With peace and prosperity for everyone in the region, and with some compensation for the refugees, we and Saudi Arabia could help on economic problems, if those are a factor. I think we could be very forthcoming.

President Asad: This would be very important for the cause of peace.

President: How do you define the Palestinian homeland? Is it your preference that it be an independent entity?

President Asad: Of course, we have to be very careful of the interests of our other brethren, both the Jordanians and the Palestinians. Our relations with King Hussein are very good, yet we have not discussed this in enough depth. They themselves want an independent state. In truth, I don’t know what the King’s enthusiasm is toward these various arrangements. His situation is complicated because there are a great number of Palestinians in Jordan. Is he enthusiastic about a union with the Palestinians? In some fashion, he did express this desire in the past, but is this a permanent position? I saw Abdul Hamid Sharaf yesterday, and he gave me some idea of the King’s visit to Washington.8 They were very pleased with it and they are very optimistic now. He said some very fine things about you, but I won’t embarrass you by repeating them.

President: Is it your inclination to go along with King Hussein’s desires on this, since I know that he will be consulting with you on it?

President Asad: Of course, we would exchange views. Jordan and Egypt must also discuss the same subject. President Sadat told the Palestinians of the need for some relationship to Jordan. But the Palestinians did not agree. They say that they would envisage a relationship after their own state is set up, but actually this is not in their mind to have a federal relationship. They envisage only an open relationship between the two states with visits, exchanges, etc. I don’t know the latest stand of President Sadat on this, or whether he has a final view of the question. There is also a question of whether King Hussein fully appreciates the situation that would develop if the two were to merge. I have never discussed this with him.

President: It’s getting late in the year and I was hoping that the Arab leaders would work this out. Although they can speak for themselves, and they may change their views, it is my impression that they do not favor a fully independent Palestinian nation. It could become radicalized with a Qadhafi-like leader. The Soviets might gain influence there. This has been my impression. King Hussein believes that if there were a vote, the Palestinians would want to affiliate themselves with Jordan. There are large numbers of Palestinians already in Jordan, and in the Government. But, of course, this cannot be predicted now. This is one question on which we had hoped that Israel and the Arab leaders would all agree, even though Arafat might not agree.

President Asad: The actual substance of a solution as envisaged would have a great bearing on whether they would accept. What is in it for them? This is what they will ask. There is one school of thought that if Jordan has hegemony over the West Bank and Gaza, then it will not be Palestinian state in its entirety. As I said to Secretary Vance, there was a time when such a solution was suggested by Henry Kissinger to King Hussein. He would have gotten a little bit of territory back and this was officially presented to him. The other thing that has been discussed is that if King Hussein has hegemony in the area, the West Bank could be demilitarized because it would be part of a Jordanian state. But, as a consequence, these propositions would divest the Palestinians of anything allowing themselves to demonstrate their own personality. So I go back to the question—what is in it for the Palestinians? At the Rabat Summit,9 there was talk about King Hussein taking part in the disengagement talks. The PLO had no role then. But King Hussein said that he had not received any serious disengagement proposals. He had only been asked to look at a final settlement on the basis of ten kilometers of withdrawal.

President: Is there some possibility of a larger confederation of Jordan and Syria, and could the West Bank be part of such a confederation?

President Asad: Jordan and Syria are moving in that direction.

President: Is this in the distant future?

President Asad: No, we are setting things up very quickly. This was our assessment some months back, but there has been some slowdown since. We have been progressing at the speed desired by our Jordanian friends. The King has showed some enthusiasm. There was a time when the King was more persistent in wanting to announce something. But what use is this if there is nothing tangible? In January 1977, we planned to announce the federation.

President: Have you ever considered that Lebanon might join?

President Asad: Some Lebanese have discussed this idea, but we have not reacted much to their advances, lest there be some connection made between our presence in Lebanon now10 and their approaches. We do not want this kind of link. Lebanon will be a burden on us in the future because of its built-in contradictions, its lack of authority, and its confusion. Even at the moment, if we withdraw, they will go back at each other’s throats. We have not encouraged such a link now, although King Hussein has been careful to want some kind of a link which would include the Lebanese. Some Lebanese have visited him on this subject. This goes on all the time. Of course, in terms of historical origins, these peoples are all one, but there are other elements now, such as security and prosperity. There are those who cannot look at the future because of present circumstances.

President: As a contribution to peace, would the PLO recognize UN Resolution 242 except for the part on the Palestinians being dealt with only as refugees?

President Asad: Even in this case, it would all depend on what we tell them they can get. There has to be a give and take. In my opinion, it would be acceptable to remove that phrase, but it would settle only the form of the problem, and we would still have to go back to a give and take. The basic objection to 242 is the reference to the Palestinians only as refugees.

President: I am not asking this now as a first step. All of the other Arabs have accepted Resolution 242. It would be very helpful at this point if the PLO also accepted it, with this one reservation. This is a reason, or an excuse, for Israel not to move for a settlement. It would help to remove an obstacle and it would not hurt the PLO to say this. It would make it easier to get Israel to move.

President Asad: In my opinion, if we manage to solve the problem of the Palestinians, we could ask them to accept what the other Arab governments have accepted, the same as the Syrians and the Egyptians and Jordan.

President: Is it your view that they would not do this before Geneva?

President Asad: (After a discussion with Foreign Minister Khad-dam) What is the importance of the Palestinians accepting Resolution 242 before Geneva?

President: The Israeli position, and that of many influential American Jews, is that the PLO is still committed to the destruction of Israel. If the PLO accepts Resolution 242, that would remove this argument. I need to have American Jewish leaders to trust me before we can make progress.

President Asad: I feel at ease about my belief that if you give the Palestinians their rights, their behavior will have to be similar to that of the Arab Governments. For them to accept in advance would be harmful to them while they are still only refugees. But having said this, I don’t mean that they would not accept what the President is suggesting. This has not been discussed with the Palestinians.

President: It is my understanding that Henry Kissinger promised Israel that we would not recognize the PLO until it recognizes Israel’s right to exist,11 and we have to honor this promise.

President Asad: I understand. My response is not opposed to your suggestion. May we set this aside for further discussion?

President: We consider it important, but it is all right to set it aside now.

President Asad: Frankly, I could feel out the Palestinians on this.

President: Please do.

President Asad: Irrespective of what Israel wishes, I would base my approach to them on what we have discussed. But it would have to be tied to the totality of the presentation on Palestinian rights, to the whole picture.

President: Let’s leave this open. There is no commitment on our part, but it may be important to talk to Arafat directly, and this is an obstacle because of our promise to Israel.

President Asad: I understand. This is what we would say to the Palestinians—we have discussed this with you. But if we say it, they will ask what else we discussed on Palestinian rights. I have understood President Carter’s suggestion on Resolution 242, but I do not understand your view on Palestinian rights.

President: I am not in a position to put forward solutions, but the Palestinians must have the right to a homeland, and my own preference would be that it be tied to Jordan or to a larger confederation. I don’t yet know how to talk about the refugee problem, since I have not yet studied it, but I will learn more. Before we go on to the definition of peace, I have one more question. We are committed to the security of Israel, to its right to exist in peace, and we are obviously interested in the security and peace of others too. This is a question that should be addressed—how to guarantee this security. We have no desire to station troops around Israel, even as a part of a UN force. But we may make some contribution if we need to. Once an agreement is reached, we will perhaps have a strong public commitment to the preservation of the arrangement.

We would like to lower the level of armaments for the whole area for all of those who are there, so that our aid could go toward economic progress and not to war. I assume you have the same desire to lower the level of military commitments. This would have to be done very carefully and on a mutual basis, but I would like your comment.

President Asad: The area has quite a few states. This is not a question of Syria alone, but there is also Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Egypt, etc. How could Egypt reduce its military forces with Libya next door?

President: You can control Libya.

President Asad: It is too far away.

President: I am mentioning this only as a distant hope.

President Asad: There are many other factors that would enter the picture. For example, President Sadat is sending forces to Zaire.12 If he had less equipment, he could not do this.

President: To what degree would you want the Soviets involved at Geneva, if we get there?

President Asad: During my last visit to Moscow, I discussed this. It is known that we have gone through a stage of difficulty with the Soviets. Therefore, we had to discuss these subjects again. When I spoke, I indicated participation of both the Soviet Union and the United States at Geneva. This was not the result of my talks with them, but merely a repetition of my previous position, which I underscored.

President: We have promised to keep the Soviets informed and we have.

President Asad: I did add in Moscow that Secretary Vance had mentioned Soviet participation in Geneva and I said that he had taken the initiative to raise this.

President: We have a desire to restore friendly relations with Iraq, so as not to let them disrupt the peace effort in the Middle East.

President Asad: That’s a good idea.

President: This is my last question. The most important issue to Israel is the nature of peace. They see leaders come and go. They want to build the basis for a lasting agreement. How do you visualize an agreement with Israel, including issues like trade, open borders, and diplomatic relations? I will meet with Crown Prince Fahd later this month and I will want to talk to him about the economic development of the region. It would be helpful if we had some feel for ideas about the possibilities of freedom of movement and of mutual economic benefits. I am sure that other nations like Japan and Germany and France would participate in the economic development of the region as well. Mr. Khaddam has pointed out the difficulties among Arab citizens in facing the question of trade and so forth, but if things go well, what can be hoped for?

President Asad: Of course, the most important thing is to prevent a new round of war. At this juncture, I will not go into the legalistic side, or discuss whether these are prerequisites for peace or not, or whether these demands by Israel are legitimate. I will not go into this. I will talk about how things could go in the future. If we can end the state of belligerency, then this would lead automatically into a state of peace. There is no intermediate stage between war and peace. When we end the state of belligerency, we will begin the state of peace. This will solve a great part of the psychological problem. An agreement could be supported by security-linked measures such as demilitarized zones. Such measures would help buy us time. These measures should be accompanied by economic development and reconstruction because this would give people confidence that the new situation is good. These measures would create psychological composure. They would be a barrier to our thinking again about war. When non-belligerency is obtained, and if the agreement goes on and lasts and is accompanied by a program of economic development, all of these measures would help to create a new era in the area.

But to say in advance that these steps must be taken, the steps that Israel insists on, would be to talk a language outside the realm of possibility. Commerce needs two partners. I cannot see anyone in Syria doing this now. Therefore, if I went on talking about trade, it would not go anywhere. It is not an integral part of peace. There are nations at peace which have no trade. But I do not want to talk in legalistic terms, but rather of how things could shape up. We could go into a condition of peace (salaam) and we support this, with many faceted measures. And this cannot help but be good.

Before Israel was created, the Jews in Arab countries had influence. They were merchants and were in our parliaments. There were more Jews in other Arab countries than in Syria, and with peace they will come back to our countries.

President: If a development fund could be created by us and the Saudis and the Iranians and the Emirates and the French and others, and if it required the cooperation of Egypt, Israel, and the Arabs to decide on expenditures for dams, etc., do you see any obstacles to that kind of cooperation?

President Asad: What would the Israeli say be in such programs? Would Israel be able to say what projects should be undertaken in Syria?

President: We are talking about projects for the region and joint projects.

President Asad: At this stage, it is hard to see the smoothness of such an idea.

President: I want to pursue this with Saudi Arabia later this month.

President Asad: Even Saudi Arabia cannot appear to agree if Israeli agreement is required. Maybe there is no objection in theory. But it will be difficult for them to participate in something like this with Israel from the outset. It could hurt Saudi Arabia to appear to agree.

President: We haven’t discussed Jerusalem. Maybe you have no interest in this.

President Asad: We are all the time talking about religion. If Jerusalem is taken from us, we would be soulless.

President: I would like to hear your thoughts on Jerusalem as our last question.

President Asad: In my opinion, the pre-1967 situation should obtain in terms of sovereignty. But there could be measures taken to guarantee access to the holy places, and other issues like this can be discussed. But that part of Jerusalem which was occupied in 1967 must go back to its owners. We could discuss the status of the religions and the movement of people. Perhaps Arab Jerusalem could be the capital of Palestine, and the other part could be the capital of Israel, but it is inconceivable that we should be clamoring for a return to the 1967 borders and exclude only Jerusalem from that.

President: Would it make it any easier if we made other exclusions as well? (Laughter.)

President Asad: If the Israelis insist on keeping Jerusalem, this shows that they do not want peace, because we are as attached to it as they are.

President: I understand and I am attached to Jerusalem also.

President Asad: This is a very sensitive issue.

- Source: Carter Library, National Security Affairs, Staff Material, Middle East File, Trips/Visits File, Box 104, 5/9/77 President Meeting with President Asadof Syria: 2–6/77. Top Secret; Sensitive. The meeting took place at the Intercontinental Hotel in Geneva. All brackets are in the original. Carter visited Geneva on May 9 to meet with Swiss President Kurt Furgler and President Asad.↩

- On November 29, 1947, the U.N. General Assembly adopted Resolution 181, which called for the creation of Jewish and Arab states in Palestine with the termination of the British Mandate on August 1, 1948. On December 11, 1948, the U.N. General Assembly adopted Resolution 194. Article 11 of that resolution stated that the refugees from the 1948 Arab-Israeli war should be permitted to return to their homes at the earliest practical date or be compensated for the loss or damage of property if they chose not to return.↩

- U.N. General Assembly Resolution 273, adopted May 11, 1949, admitted Israel into the United Nations.↩

- The Armistice Agreements were actually negotiated and signed in 1949. See footnote 5, Document 18.↩

- See footnote 9, Document 21.↩

- See Document 14.↩

- No record of this conversation has been found.↩

- See Documents 30 and 31.↩

- See footnote 8, Document 6.↩

- Syrian troops remained in Lebanon to keep the peace after the cease-fire in 1976. See footnote 14, Document 7.↩

- See, for example, the report of Kissinger’s discussions with Israeli leaders in February 1975 in Foreign Relations, 1969–1976, vol. XXVI, Arab-Israeli Dispute, 1974-1976, Document 131. Kissinger reiterated in his memoirs that the United States would not negotiate with the PLO “so long as the PLO engaged in terrorism and maintained its charter calling for the destruction of Israel.” (Years of Renewal, p. 356)↩

- See footnote 10, Document 27.↩